Vertical integration

| Marketing |

|---|

In microeconomics, management, and international political economy, vertical integration refers to an arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is integrated and owned by that company. Usually each member of the supply chain produces a different product or (market-specific) service, and the products combine to satisfy a common need. It is contrasted with horizontal integration, wherein a company produces several items that are related to one another. Vertical integration has also described management styles that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership but also into one corporation (as in the 1920s when the Ford River Rouge Complex began making much of its own steel rather than buying it from suppliers).

Vertical integration and expansion is desired because it secures supplies needed by the firm to produce its product and the market needed to sell the product. Vertical integration and expansion can become undesirable when its actions become anti-competitive and impede free competition in an open marketplace. Vertical integration is one method of avoiding the hold-up problem. A monopoly produced through vertical integration is called a vertical monopoly.

Vertical expansion[]

Vertical integration is often closely associated with vertical expansion which, in economics, is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of companies that produce the intermediate goods needed by the business or help market and distribute its product. Such expansion is desired because it secures the supplies needed by the firm to produce its product and the market needed to sell the product. Such expansion can become undesirable when its actions become anti-competitive and impede free competition in an open marketplace.

The result is a more efficient business with lower costs and more profits. On the undesirable side, when vertical expansion leads toward monopolistic control of a product or service then regulative action may be required to rectify anti-competitive behavior. Related to vertical expansion is lateral expansion, which is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of similar firms, in the hope of achieving economies of scale.

Vertical expansion is also known as a vertical acquisition. Vertical expansion or acquisitions can also be used to increase sales and to gain market power. The acquisition of DirecTV by News Corporation is an example of forwarding vertical expansion or acquisition. DirecTV is a satellite TV company through which News Corporation can distribute more of its media content: news, movies, and television shows. The acquisition of NBC by Comcast is an example of backward vertical integration. For example, in the United States, protecting the public from communications monopolies that can be built in this way is one of the missions of the Federal Communications Commission.

Three types of vertical integration[]

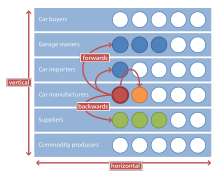

Contrary to horizontal integration, which is a consolidation of many firms that handle the same part of the production process, vertical integration is typified by one firm engaged in different parts of production (e.g., growing raw materials, manufacturing, transporting, marketing, and/or retailing). Vertical integration is the degree to which a firm owns its upstream suppliers and its downstream buyers.

There are three varieties of vertical integration: backward (upstream) vertical integration, forward (downstream) vertical integration, and balanced (both upstream and downstream) vertical integration.

- A company exhibits backward vertical integration when it controls subsidiaries that produce some of the inputs used in the production of its products. For example, an automobile company may own a tire company, a glass company, and a metal company. Control of these three subsidiaries is intended to create a stable supply of inputs and ensure a consistent quality in their final product. It was the main business approach of Ford and other car companies in the 1920s, who sought to minimize costs by integrating the production of cars and car parts, as exemplified in the Ford River Rouge Complex.

- A company tends toward forward vertical integration when it controls distribution centers and retailers where its products are sold. An example is a brewing company that owns and controls a number of bars or pubs.

Disintermediation is a form of vertical integration when purchasing departments take over the former role of wholesalers to source products.[3]

Problems and benefits[]

There are internal and external society-wide gains and losses stemming from vertical integration, which vary according to the state of technology in the industries involved, roughly corresponding to the stages of the industry lifecycle.[clarification needed][citation needed] Static technology represents the simplest case, where the gains and losses have been studied extensively.[citation needed] A vertically integrated company usually fails when transactions within the market are too risky or the contracts to support these risks are too costly to administer, such as frequent transactions and a small number of buyers and sellers.

Internal gains[]

- Lower transaction costs

- Synchronization of supply and demand along the chain of products

- Lower uncertainty and higher investment

- Ability to monopolize market throughout the chain by market foreclosure

- Strategic independence (especially if important inputs are rare or highly volatile in price, such as rare-earth metals).

Internal losses[]

- Higher monetary and organizational costs of switching to other suppliers/buyers

- Weaker motivation for good performance at the start of the supply chain since sales are guaranteed and poor quality may be blended into other inputs at later manufacturing stages

- Specific investment

Benefits to society[]

- Better opportunities for investment growth through reduced uncertainty[citation needed]

- Local companies are often better positioned against foreign competition[citation needed]

- Lower consumer prices by reducing markup from intermediaries[4]

Losses to society[]

- Monopolization of markets

- Rigid organizational structure

- Manipulation of prices (if market power is established)

- Loss of tax revenue as fewer intermediary transactions are made[citation needed]

Selected examples[]

Birdseye[]

During a hunting trip American explorer and scientist Clarence Birdseye discovered the beneficial effects of "quick-freezing". For example, fish caught a few days previously that were kept in ice remained in perfect condition.

In 1924, Clarence Birdseye patented the "Birdseye Plate Froster" and established the General Seafood Corporation. In 1929, Birdseye's company and the patent were bought by Postum Cereals and Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation. It was later known as General Foods. They kept the Birdseye name, which was split into two words (Birds eye) for use as a trademark. Birdseye was paid $20 million for the patents and $2 million for the assets.

Birds Eye was one of the pioneers in the frozen food industry. During these times, there was not a well-developed infrastructure to produce and sell frozen foods. Hence Birds Eye developed its own system by using vertical integration. Members of the supply chain, such as farmers and small food retailers, couldn't afford the high cost of equipment, so Birdseye provided it to them.

Until now, Birds Eye has faded slowly because they have fixed costs associated with vertical integration, such as property, plants, and equipment that cannot be reduced significantly when production needs decrease. The Birds Eye company used vertical integration to create a larger organization structure with more levels of command. This produced a slower information processing rate, with the side effect of making the company so slow that it couldn't react quickly. Birds Eye didn't take advantage of the growth of supermarkets until ten years after the competition did. The already-developed infrastructure did not allow Birdseye to quickly react to market changes.

Alibaba[]

In order to increase profits and gain more market share, Alibaba, a China-based company, has implemented vertical integration deepening its company holdings to more than the e-commerce platform. Alibaba has built its leadership in the market by gradually acquiring complementary companies in a variety of industries including delivery and payments.

Steel and oil[]

One of the earliest, largest and most famous examples of vertical integration was the Carnegie Steel company. The company controlled not only the mills where the steel was made, but also the mines where the iron ore was extracted, the coal mines that supplied the coal, the ships that transported the iron ore and the railroads that transported the coal to the factory, the coke ovens where the coal was coked, etc. The company focused heavily on developing talent internally from the bottom up, rather than importing it from other companies.[5][full citation needed] Later, Carnegie established an institute of higher learning to teach the steel processes to the next generation.

Oil companies, both multinational (such as ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, ConocoPhillips or BP) and national (e.g., Petronas) often adopt a vertically integrated structure, meaning that they are active along the entire supply chain from locating deposits, drilling and extracting crude oil, transporting it around the world, refining it into petroleum products such as petrol/gasoline, to distributing the fuel to company-owned retail stations, for sale to consumers.[citation needed] Standard Oil is a famous example of both horizontal and vertical integration, combining extraction, transport, refinement, wholesale distribution, and retail sales at company-owned gas stations.

Telecommunications and computing[]

Telephone companies in most of the 20th century, especially the largest (the Bell System) were integrated, making their own telephones, telephone cables, telephone exchange equipment and other supplies.[6]

Entertainment[]

From the early 1920s through the early 1950s, the American motion picture had evolved into an industry controlled by a few companies, a condition known as a "mature oligopoly", as it was led by eight major film studios, the most powerful of which were the "Big Five" studios: MGM, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, Paramount Pictures, and RKO.[7] These studios were fully integrated, not only producing and distributing films, but also operating their own movie theaters; the "Little Three", Universal Studios, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists, produced and distributed feature films but did not own theaters.[citation needed]

The issue of vertical integration (also known as common ownership) has been the main focus of policy makers because of the possibility of anti-competitive behaviors affiliated with market influence. For example, in United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., the Supreme Court ordered the five vertically integrated studios to sell off their theater chains and all trade practices were prohibited (United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 1948).[8] The prevalence of vertical integration wholly predetermined the relationships between both studios and networks[clarification needed] and modified criteria in financing. Networks began arranging content initiated by commonly owned studios and stipulated a portion of the syndication revenues in order for a show to gain a spot on the schedule if it was produced by a studio without common ownership.[9] In response, the studios fundamentally changed the way they made movies and did business. Lacking the financial resources and contract talent they once controlled, the studios now relied on independent producers supplying some portion of the budget in exchange for distribution rights.[10]

Certain media conglomerates may, in a similar manner, own television broadcasters (either over-the-air or on cable), production companies that produce content for their networks, and also own the services that distribute their content to viewers (such as television and internet service providers). AT&T, Bell Canada, Comcast, Sky plc, and Rogers Communications are vertically integrated in such a manner—operating media subsidiaries (such as WarnerMedia, Bell Media, NBCUniversal, and Rogers Media), and provide "triple play" services of television, internet, and phone service in some markets (such as Bell Satellite TV/Bell Internet, Rogers Cable, Xfinity, and Sky's satellite TV and internet services). Additionally, Bell and Rogers own wireless providers, Bell Mobility and Rogers Wireless, while Comcast is partnered with Verizon Wireless for an Xfinity-branded MVNO. Similarly, Sony has media holdings through its Sony Pictures division, including film and television content, as well as television channels, but is also a manufacturer of consumer electronics that can be used to consume content from itself and others, including televisions, phones, and PlayStation video game consoles. AT&T is the first ever vertical integration where a mobile phone company and a film studio company are under same umbrella.

Agriculture[]

Vertical integration through production and marketing contracts have also become the dominant model for livestock production. Currently, 90% of poultry, 69% of hogs, and 29% of cattle are contractually produced through vertical integration.[11] The USDA supports vertical integration because it has increased food productivity. However, "... contractors receive a large share of farm receipts, formerly assumed to go to the operator's family".[12]

Under production contracts, growers raise animals owned by integrators. Farm contracts contain detailed conditions for growers, who are paid based on how efficiently they use feed, provided by the integrator, to raise the animals. The contract dictates how to construct the facilities, how to feed, house, and medicate the animals, and how to handle manure and dispose of carcasses. Generally, the contract also shields the integrator from liability.[11] Jim Hightower, in his book, Eat Your Heart Out,[13] discusses this liability role enacted by large food companies. He finds that in many cases of agricultural vertical integration, the integrator (food company) denies the farmer the right of entrepreneurship. This means that the farmer can only sell under and to the integrator. These restrictions on specified growth, Hightower argues, strips the selling and producing power of the farmer. The producer is ultimately limited by the established standards of the integrator. Yet, at the same time, the integrator still keeps the responsibility connected to the farmer. Hightower sees this as ownership without reliability.[14]

Under marketing contracts, growers agree in advance to sell their animals to integrators under an agreed price system. Generally, these contracts shield the integrator from liability for the grower's actions and the only negotiable item is a price.[11]

Automotive industry[]

In the United States new automobiles can not be sold at dealerships owned by the same company that produced them but are protected by state franchise laws.[15]

Eyewear[]

EssilorLuxottica, the company that merged with Essilor and Luxottica, occupies up to 30% of the global market share as well as representing billions of pairs of lenses and frames sold annually. Before the merger, Luxottica also owned 80% of the market share of companies that produce corrective and protective eyewear as well as owning many retailers, optical departments at Target and Sears, and key eye insurance groups, such as EyeMed, many of which are already part of the now merged company.[16][17][18][19]

Health care[]

In the United States, major vertical mergers have included CVS Health's purchase of Aetna, and Cigna's purchase of Express Scripts.

General retail[]

Amazon.com has been criticized for being anti-competitive as both an owner and participant of its dominant online marketplace. In office products, Sycamore Partners owns both Staples, Inc., a major retailer, and Essendant, a dominant wholesaler.

Economic theory[]

In economic theory, vertical integration has been studied in the literature on incomplete contracts that was developed by Oliver Hart and his coauthors.[20][21] Consider a seller of an intermediate product that is used by a buyer to produce a final product. The intermediate product can only be produced with the help of specific physical assets (e.g., machines, buildings). Should the buyer own the assets (vertical integration) or should the seller own the assets (non-integration)? Suppose that today the parties have to make relationship-specific investments. Since today complete contracts cannot be written, the two parties will negotiate tomorrow about how to divide the returns of the investments. Since the owner is in a better bargaining position, he will have stronger incentives to invest. Hence, whether vertical integration is desirable or not depends on whose investments are more important. Hart's theory has been extended by several authors. For instance, DeMeza and Lockwood (1998) have studied different bargaining games,[22] while Schmitz (2006) has introduced asymmetric information into the incomplete contracting setup.[23] In these extended models, vertical integration can sometimes be optimal even if only the seller has to make an investment decision.

References[]

- ^ Unoki, Ko: Mergers, Acquisitions and Global Empires: Tolerance, Diversity and the Success of M&A. (New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 34–64

- ^ Grenville, Stephen (3 November 2017). "The first global supply chain". Lowy Institute. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Stephen Grenville (2017): "Here [17th-century Ternate, North Maluku, Indonesia], surely, was a very early, fully operational manifestation of international integration, the embryonic form of today's ubiquitous globalisation. We would recognise its constituent elements. Here was the tenuous but well-structured supply-chain, extended all the way from Banda to Amsterdam, via numerous ports and functionaries, administered with brutal efficiency by the Dutch East India Company, perhaps the first business organisation that bears resemblance to today's multinational corporations. The company raised money by issuing shares. It had the first widely-recognised commercial logo. Even without today's computers, the company's officials were linked through a hierarchy of regular detailed reporting and accounting. Production was brought together in plantations and processed in 'factories'. Near-subsistence agriculture was replaced with scale and quality control, supervised by the perkeniers with an incentivising profit-sharing deal with the company. Customer feedback was insistently relayed to producers: 'small nutmegs are of no value'. This mighty machine produced 3000 tons of nutmeg annually and transported it across hazardous waters to deliver it to the burghers of Holland and on to the rest of Europe's spice-hungry upper-class. Ad hoc trade between nations, with goods passing through many hands, many owners and many markets, was replaced by 'straight-through' processing by a single entity – the Dutch East India Company."

- ^ Lazonick, William; David J. Teece (2012). Management Innovation: Essays in the Spirit of Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. OUP Oxford. p. 150. ISBN 978-0199695683. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ DOJ and FTC Propose Highly Anticipated Vertical Merger Guidelines

- ^ Folsom, Burton The Myth of the Robber Barons 5th edition. 2007. pg. 65. ISBN 978-0963020314. "only we can develop ability and hold it in our service. Every year should be marked by the promotion of one or more of our young men."

- ^ Irwin, Manley (3 February 1968). "Vertical Integration and the Communication Equipment Industry Alternatives for Public Policy". scholarship.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ John Alberti (27 November 2014). Screen Ages: A Survey of American Cinema. Routledge. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-317-65028-7.

- ^ Oba, Goro; Chan-Olmstead, Sylvia (2006). "Self-Dealing or Market Transaction?: An Exploratory Study of Vertical Integration in the U.S. Television Syndication Market". Journal of Media Economics. 19 (2): 99–118. doi:10.1207/s15327736me1902_2. S2CID 153386365.

- ^ Lotz, Amanda D. (2007) "The Television Will Be Revolutionized". New York, NY: New York University Press. p.87

- ^ McDonald, P. & Wasko, J. (2008). The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Australia: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 14–17. ISBN 9781405133876.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paul Stokstad, Enforcing Environmental Law in an Unequal Market: The Case of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, 15 Mo. Envtl. L. & Pol’y Rev. 229, 234-36 (Spring 2008)

- ^ "USDA ERS - Farmers' Use of Marketing and Production Contracts". Ers.usda.gov. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Hightower, Jim (21 October 2009). Eat Your Heart Out: Food Profiteering in America - Jim Hightower - Google Books. ISBN 9780517524541. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Hightower, Jim. Eat Your Heart Out, 1975, Crown Publishing. pg 162-168, ISBN 978-0517524541

- ^ Surowiecki, James (4 September 2006). "Dealer's Choice". The New Yorker. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ "Sticker shock: Why are glasses so expensive?". 60 Minutes. CBS News. 7 October 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Goodman, Andrew (16 July 2014). "There's More to Ray-Ban and Oakley Than Meets the Eye". Forbes. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ Swanson, Ana (10 September 2014). "Meet the Four-Eyed, Eight-Tentacled Monopoly That is Making Your Glasses So Expensive". Forbes. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ Knight, Sam (10 May 2018). "The spectacular power of Big Lens | The long read" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Grossman, Sanford J.; Hart, Oliver D. (1986). "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration". Journal of Political Economy. 94 (4): 691–719. doi:10.1086/261404. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ^ Hart, Oliver; Moore, John (1990). "Property Rights and the Nature of the Firm". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (6): 1119–1158. doi:10.1086/261729. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 15892859.

- ^ de Meza, D.; Lockwood, B. (1998). "Does Asset Ownership Always Motivate Managers? Outside Options and the Property Rights Theory of the Firm". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 113 (2): 361–386. doi:10.1162/003355398555621. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ^ Schmitz, Patrick W. (2006). "Information Gathering, Transaction Costs, and the Property Rights Approach". American Economic Review. 96 (1): 422–434. doi:10.1257/000282806776157722. S2CID 154717219.

Bibliography[]

- Kathryn H. (1986). "Matching Vertical Integration strategies". Strategic Management Journal. 7: 535–555. doi:10.1002/smj.4250070605.

- Matthew Lewis (2013). "On Apple And Vertical Integration". Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Paul Cole-Ingait; Demand Media (2013). "Vertical Integration Examples in the Smartphone Industry". Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Robert D. Buzzell (January 1983). "Is Vertical Integration Profitable?". Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Wharton (2012). "How Apple Made 'Vertical Integration' Hot Again — Too Hot, Maybe". Time. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- "Idea Vertical Integration". 30 March 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Grossman SJ, Hart OD (1986). "The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration" (PDF). The Journal of Political Economy. 94 (4): 691–719. doi:10.1086/261404.

- "Iglo History". Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

Further reading[]

- Bramwell G. Rudd, 2014, "Courtaulds and the Hosiery & Knitwear Industry," Lancaster, PA:Carnegie.

- Joseph R. Conlin, 2007, "Vertical Integration," in The American Past: A Survey of American History, p. 457, Belmont, CA:Thompson Wadsworth.

- Martin K. Perry, 1988, "Vertical Integration: Determinants and Effects," Chapter 4 in Handbook of Industrial Organization, North Holland.[full citation needed]

- Market structure

- Business terms

- Supply chain management

- Mass production

- Marketing strategy