Victor Ninov

Victor Ninov (Bulgarian: Виктор Нинов, born 1959) is a physicist and former researcher who worked primarily in creating heavy elements. He is known for the co-discoveries of elements 110, 111, and 112 and the alleged fabrication of the evidence used to claim the creation of elements 116 and 118.

Early life[]

Victor Ninov was born in Bulgaria in 1959.[1] He grew up in the capital city of Sofia.[2] In the 1970s, when Ninov was a teenager, he and his family left for West Germany; they bounced around from house to house.[1] Shortly after the move Victor's father went missing, and turned up dead six months later in the Bulgarian foothills due to causes unknown.[1]

Career[]

Victor Ninov attended Technische Universität Darmstadt near Frankfurt, Germany.[1][3] Here he distinguished himself as very capable physicist: he was particularly good at building scientific instruments and coding analysis programs for them.[1][4]

This landed him a job at the nearby German research center GSI (Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung) where he worked on his doctorate and postdoctoral work of creating new elements.[1][5]

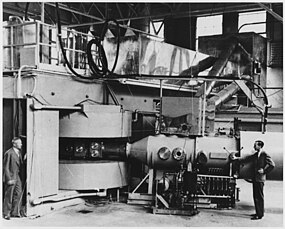

For his expertise he was given sole control of the computer analysis program.[1] Here he became a rising star by co-discovering elements 110, 111, and 112 (darmstadtium, roentgenium, and copernicium respectively) by smashing ion beams into heavy elements using GSI's UNILAC (a type of particle accelerator) and analyzing the debris.[1][4] These discoveries were made with the help of his addition of a gas separator to the particle accelerator to help filter out everything but the heavy elements they were looking for.

He worked at Stanford University for a time.[2] He was hired at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) in 1996 as a world class expert for particle accelerator debris sensors, and analysis programs.[1]

Fraud[]

While working at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) Victor Ninov and his team pursued a hypothesis that element 118 could be formed at relatively low energies by smashing 86Kr and 208Pb ions together.[6][1] Ninov initially doubted the hypothesis he was pursuing; he is quoted in saying "We didn't know how many orders of magnitude he was wrong" of the scientist who created the hypothesis.[1]

Ninov, again, held sole control of the data analysis program, and he was the only one on the team that knew how to use it.[1] In 1999 Ninov and his team reported sightings of element 118, almost exactly as predicted, and a decay chain that also produced element 116.[1][7][4][6] However, other laboratories were unable to reproduce the results.[8]

Eager to prove their discovery, the team double checked their instruments, and tried again.[1] One more sighting was made by Ninov, but it was dismissed by a colleague, and a full formal investigation was spawned to get to the bottom of elements 118 and 116.[1] The original element 118 data was independently analysed, and in the original binary data, there was no indication of the presence of element 118 or 116.[1][7][4][6][8] The investigation dragged on for a year, until it was concluded that "Ninov... intentionally misled his colleagues-and everyone else-by fabricating data".[8]

Ninov, who had been placed on leave, was fired.[1][4] The rest of Ninov's team officially retracted their claims in 2002.[7] There was also an investigation conducted into Ninov's unsupervised science at GSI; it was found that "two sightings were spuriously created" (one of element 110 and another of element 112).[4] However, very perplexingly, these false flags were found amongst lots of real data that still supported that his co-discoveries were legitimate.[4] It was the conclusion of the GSI investigation that "the discovery of elements 111 and 112 still stands".[4] At minimum it is certain that Victor Ninov made a "wrongful claim" about elements 118 and 116.[7]

The heavy elements 116 and 118 were eventually discovered and verified in the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, and were observed contrary to LBNLs observations.[8] These elements were named livermorium and oganesson respectively.[9][10] Ninov maintains that he was innocent to this day.[1]

Impact of fraud on scientific community[]

This fraud came as quite a shock to other scientists as Ninov had been previously regarded as a very respected physicist.[1] In the aftermath of the fraud it was troubling to many that so many co-authors on the papers about LBNL were none the wiser, to learn they had contributed to a false statement.[11] So, in a twist of fate, the falsifying of scientific data by Ninov resulted in stricter guidelines being set for coauthors; these rules "clarify co-authors' roles and duties" and they are "requiring all coauthors to vouch for their contribution to published work".[11][12]

The American Physical Society has also called for increased ethical training and oversight at research institutions, and has sponsored several speakers in an effort to make the scientific community more comfortable and resilient to scientific fraud.[12] Reports on the Ninov affair were released around the same time as the final report on the Schön affair, another major incident of fraud in physics, and this amplified its impact.[12]

Current life[]

Ninov is retired from physics.[2] He lives in California.[2] His wife, Caroline Cox, a former history professor at University of the Pacific, died in 2014 of cancer.[2] They were married 29 years.[2] Ninov helped finish her book, Boy Soldiers of the American Revolution, and it was published postmortem.[2] He is an avid sailor, and pilots a four-seat plane.[2]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Monastersky, Richard (16 August 2002). "Atomic Lies: How One Physicist May Have Cheated in the Race to Find New Elements". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Sauro, Tony (July 2016). "Final assignment: Family, friends and colleagues help complete late Pacific professor's book". recordnet.

- ^ Darmstadt, Technische Universität. "Welcome to TU Darmstadt". Technische Universität Darmstadt. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Dalton, Rex (2002). "California lab fires physicist over retracted finding". Nature. 418 (6895): 261. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..261D. doi:10.1038/418261b. PMID 12124581.

- ^ "About us". GSI. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Seife, Charles (July 2002). "Heavy-element fizzle laid to falsified data. (Heavy-Ion Physics)". Science.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Schwarzschild, Bertram (2002). "Lawrence Berkeley Lab concludes that evidence of element 118 was a fabrication". Physics Today. 55 (9): 15–. Bibcode:2002PhT....55i..15S. doi:10.1063/1.1522199.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Weiss, P (July 2002). "Heavy Suspicion". Science News. 162: 2 – via Academic Search Complete.

- ^ Ninov, Viktor (1999). "Observation of Superheavy Nuclei Produced in the Reaction of 86Kr with 208Pb". Physical Review Letters. 83 (6): 1104–1107. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.1104N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1104.

- ^ Johnson, George (15 October 2002). "At Lawrence Berkeley, Physicists Say a Colleague Took Them for a Ride". The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Park, Robert L (2008). "Fraud in Science". Social Research. 75 (4): 1135–1150. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.1389. doi:10.1353/sor.2008.0010 (inactive 31 May 2021).CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2021 (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Overbye, Dennis (19 November 2002). "After Two Scandals, Physics Group Expands Ethics Guidelines". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

External links[]

- Observation of Superheavy Nuclei Produced in the Reaction of 86Kr with 208Pb – Communication in "Physical Review Letters" stating observation of the element 118 published by Victor Ninov's research group

- Sanacacio.net Copy of NY Times article on the Ninov controversy

- Atomic Lies An essay about V. Ninov's career

- Living people

- 1959 births

- Academic scandals

- American nuclear physicists

- American people of Bulgarian descent

- Bulgarian nuclear physicists

- People involved in scientific misconduct incidents

- University of California, Berkeley staff

- Technische Universität Darmstadt alumni

- Oganesson

- Livermorium