Vietnamese language and computers

The Vietnamese language is written with a Latin script with diacritics (accent tones) which requires several accommodations when typing on phone or computers. Software-based systems are a form of writing Vietnamese on phones or computers with software that can be installed on the device or from third party software such as UniKey. Telex is the oldest input method devised to encode the Vietnamese language with its tones. Other input methods may also include VNI (Number key-based keyboard) and VIQR. VNI input method is not to be confused with VNI code page.

Historically, Vietnamese was also written in chữ Nôm, which is mainly used for ceremonial and traditional purposes in recent times, and remains in the field of historians and philologists. Sometimes, Vietnamese is can also be typed without tone marks which Vietnamese speakers can usually guess depending on context.

Fonts and character encodings[]

Vietnamese alphabet[]

There are as many as 46 character encodings for representing the Vietnamese alphabet.[1] Unicode has become the most popular form for many of the world's writing systems, due to its great compatibility and software support. Diacritics may be encoded either as combining characters or as precomposed characters, which are scattered among the Latin Extended-A, Latin Extended-B, and Latin Extended Additional blocks. The Vietnamese đồng symbol is encoded in the Currency Symbols block. Historically, the Vietnamese language used other characters beyond the modern alphabet. The Middle Vietnamese letter B with flourish (ꞗ) is included in the Latin Extended-D block. The apex is not included in Unicode, but U+1DC4 ◌᷄ COMBINING MACRON-ACUTE may serve as a rough approximation.

Early versions of Unicode assigned the characters U+0340 ◌̀ COMBINING GRAVE TONE MARK and U+0341 ◌́ COMBINING ACUTE TONE MARK for the purpose of placing these marks beside a circumflex, as is common in Vietnamese typography. These two characters have been deprecated; U+0301 ◌́ COMBINING ACUTE ACCENT and U+0300 ◌̀ COMBINING GRAVE ACCENT are now used regardless of any present circumflex.[2]

For systems that lack support for Unicode, dozens of 8-bit Vietnamese code pages have been designed.[1] The most commonly used of them were VISCII, VSCII (TCVN 5712:1993), VNI, VPS and Windows-1258.[3][4] Where ASCII is required, such as when ensuring readability in plain text e-mail, Vietnamese letters are often encoded according to Vietnamese Quoted-Readable (VIQR) or VSCII Mnemonic (VSCII-MNEM),[5] though usage of either variable-width scheme has declined dramatically following the adoption of Unicode on the World Wide Web. For instance, support for all above mentioned 8-bit encodings, with the exception of Windows-1258, was dropped from Mozilla software in 2014.[6]

Many Vietnamese fonts intended for desktop publishing are encoded in VNI or TCVN3 (VSCII).[4] Such fonts are known as "ABC fonts".[7] Popular web browsers lack support for specialty Vietnamese encodings, so any webpage that uses these fonts appears as unintelligible mojibake on systems without them installed.

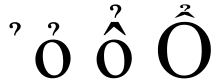

Vietnamese often stacks diacritics, so typeface designers must take care to prevent stacked diacritics from colliding with adjacent letters or lines. When a tone mark is used together with another diacritic, offsetting the tone mark to the right preserves consistency and avoids slowing down saccades.[8] In advertising signage and in cursive handwriting, diacritics often take forms unfamiliar to other Latin alphabets. For example, the lowercase letter I retains its tittle in ì, ỉ, ĩ, and í.[9] These nuances are rarely accounted for in computing environments.

Approaches[]

Vietnamese writing requires 134 additional letters (between both cases) besides the 52 already present in ASCII.[10] This exceeds the 128 additional characters available in a conventional extended ASCII encoding. Although this can be solved by using a variable-width encoding (as is done by UTF-8), a number of approaches have been used by other encodings to support Vietnamese without doing so:

- Replace at least six ASCII characters, selected either for being uncommon in Vietnamese, and/or for being non-invariant in ISO 646 or DEC NRCS[10] (as in VNI for DOS).

- Drop the uppercase letters which are least frequently used,[10] or all uppercase letters with tone marks (as in VSCII-3 (TCVN3)). These letters may still be supplied by means of all-capital fonts.[11]

- Drop forms of the letter Y with tone marks, necessitating use of the letter I in those circumstances. This approach was rejected by the designers of VISCII on the basis that a character encoding should not attempt to settle a spelling reform issue.[10]

- Replace at least six C0 control characters[10] (as in VISCII, VSCII-1 (TCVN1) and VPS).

- Use combining characters, allowing one vowel with accents to be fully represented using a sequence of characters (as in VNI, VSCII-2 (TCVN2), Windows-1258 and ANSEL).