Walking (Thoreau)

This article possibly contains original research. (February 2015) |

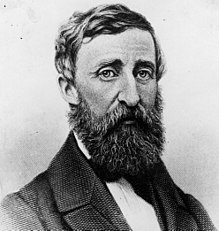

Walking, or sometimes referred to as "The Wild", is a lecture by Henry David Thoreau first delivered at the Concord Lyceum on April 23, 1851. It was written between 1851 and 1860, but parts were extracted from his earlier journals. Thoreau read the piece a total of ten times, more than any other of his lectures. "Walking" was first published as an essay in the Atlantic Monthly after his death in 1862.[1]

Transcendentalism in Walking/Form[]

"Walking" is a transcendental essay that analyzes the relationship between man and nature, trying to find a balance between society and our raw animal nature.

I would not have every man nor every part of a man cultivated, any more than I would have every acre of earth cultivated: part will be tillage, but the greater part will be meadow and forest.[2]

Part of Nature[]

I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil, -to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society.[3]

Learn From Nature[]

I derive more of my subsistence from the swamps which surround my native town than from the cultivated gardens in the village.[4]

Nature is a spiritual Experience[]

According to Thoreau, and just as Emerson, being in nature is a spiritual experience, which shapes who we are,

For I believe that climate does thus react on man- as there is something in the mountain- air that feds the spirit and inspires. Will not man grow to greater perfection intellectually as well as physically under these influences?.[5]

Themes[]

Self-Reflection[]

Moreover, you must walk like a camel, which is said to be the only beast which ruminates when walking.[6]

In my afternoon walk I would fain forget all my morning occupations and my obligations to society. But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village…What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something other than the woods?.[7]

The Wild and Society[]

Thoreau says,

all good things are wild and free.[8]

I rejoice that horses and steers have to be broken before they can be made the slaves of men, and that men themselves have some wild oat still left to sow before they become submissive members of society.[9]

here is this vast, savage, howling mother of ours, Nature, lying all around, with such beauty, and such affection for her children, as the leopard; and yet we are so early weaned from her breast to society, to that culture which is exclusively an interaction of man on man….[10]

Exploration[]

We go eastward to realize history and study the works of art and literature, retracing the steps of the race; we go westward as into the future, with a spirit of enterprise and adventure. The Atlantic is a Leathean stream, in our passage over which we have had an opportunity to forget the Old World and its institutions.[11]

Writing Style[]

“Walking” has autobiographical side of Henry David Thoreau as well, and reflects the author’s personal experiences.[12] As Rebecca Solnit has stated in “Wanderlust: A History of Walking”, the rhythm of walking could be the sources of music, conversation, thoughts, and literature.[13] In over ten years of walking, Thoreau kept observing nature, organizing his thought, and considering the best way to express his lecture; his diary shows what elements in his daily life influenced his environmental view and motivated him to write it. Above all, the author’s correspondence with friends provides not only his lecture career but also his works and his writing process. As a result, his essay is told by the voice of the confident narrator, given some authority.[14] Moreover, using allusion, he succeeded in not only understanding the essay broader but also obtaining a form of poetry, and with his lecture and the new writing style, “Walking” became a new critique of the existing society.

See also[]

- Walden

- The Old Marlborough Road, a poem within "Walking"

References[]

- ^ "Walking". The Atlantic Monthly, A Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. IX (LVI): 657–674. June 1862. Retrieved February 1, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 656.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 627.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 646.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 642.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 631.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 632.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 652.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 653.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 655.

- ^ Thoreau (2000), p. 638.

- ^ Palmer, Scott. “Why Go Straight?: Stepping Out with Henry David Thoreau's ‘Walking’ and Edward Thomas' ‘The Icknield Way.’ Vol. 12, No. 1 (Winter 2005), pp. 115-129 (15 pages).

- ^ Walker, Jennie Lynn. “Beyond the book: The compositional, lecture, and publication histories of Henry David Thoreau's ‘Walking’ read ecocritically.”

- ^ Schuchalter, Jerry. “’What Makes Alfred Walk?’: Alfred Kazin's ‘A Walker in the City’—A Rewriting of Henry David Thoreau's ‘Walking’ Essay.” Vol. 21, Days of Wonder: Nights of Light (2002), pp. 24-38 (15 pages).

- Thoreau, Henry (2000). Atkinson, Brooks (ed.). Walden and Other Writings. New York: Random House, Inc. ISBN 9780679783343.

- Walking at Project Gutenberg

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A complete collection of Thoreau's essays, including Walking at Standard Ebooks

- Walking. As published in Atlantic Monthly, 1862. https://www.walden.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Walking-1.pdf

- Nationalism and the Nature of Thoreau's "Walking" Andrew Menard. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/TNEQ_a_00229

- 1861 essays

- American essays

- Essays by Henry David Thoreau