Warrior (comics)

| Warrior | |

|---|---|

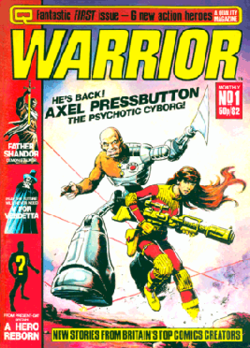

Warrior #1 (March 1982), featuring an image of Axel Pressbutton by Steve Dillon. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Quality Communications |

| Schedule | Monthly |

| Format | Ongoing series |

| Genre | |

| Publication date | March 1982 – January 1985 |

| No. of issues | 26 |

| Main character(s) | Marvelman V Axel Pressbutton |

| Creative team | |

| Created by | Dez Skinn |

| Written by | Alan Moore Steve Moore |

| Artist(s) | Steve Dillon Garry Leach |

Warrior was a British comics anthology that ran for 26 issues between March 1982 and January 1985. It was edited by Dez Skinn and published by his company Quality Communications. It featured early work by comics writer Alan Moore, including V for Vendetta and Marvelman.

This series of 26 issues in the 1980s was essentially a Volume #2; Skinn had edited/published #s 1-6 of a black-and-white fanzine version of Warrior (full title: Warrior: Heroic Tales Of Swords and Sorcery) in 1974-75, with reprint and new strips, art and writing from Steve Parkhouse, Dave Gibbons [designed logo], Michael Moorcock, Frank Bellamy, Don Lawrence, Barry Windsor-Smith, et al.[1]

Rivalling 2000 AD, Warrior won 17 Eagle Awards during its short run (including nine Eagles in 1983 alone).[2] Because of traditional distribution and its format, it was one of the comic books in the British market that didn't just rely upon distribution through then format-driven specialist shops and expensive subscriptions for its sales base.

History[]

Skinn, former editorial director of Marvel UK, launched Warrior in an effort to create a similar mix of stories to the one he had previously put together for Marvel's Hulk Weekly, but with greater creative freedom and a measure of creator ownership. The title was recycled from a short-lived reprint series Skinn had once published; he remarked that "Warrior seemed an obvious choice nobody else had picked up on—both times! It fit perfectly as a newsstand logo."[3] He recruited many of the writers and artists he had previously worked with at Marvel, including Steve Moore, John Bolton, Steve Parkhouse and David Lloyd, adding established creators like Brian Bolland and Dave Gibbons, and emerging young talent such as Alan Moore, Garry Leach, Alan Davis and Steve Dillon.

Skinn decided to revive Marvelman, a popular British superhero from the 1950s with a massive backlog of available pages, reasoning that "given the difference between a brand-new character who would sell no more copies, or a somewhat forgotten character who might sell about a dozen more, I opted to follow the similar relaunch I’d done with Captain Britain—tease at first, then, as a bonus, surprise those who actually cared. If it failed, it was only six pages out of 52—the beauty of the anthology approach."[3] Skinn offered the writing first to Parkhouse who had earlier worked for Marvel, then Steve Moore, who had worked on the pre-Marvel UK US-reprint line Power Comics. Neither were interested, and Moore suggested a friend Alan Moore (no relation)[3] who had said in a fanzine that he had an ambition to revive the character. Alan Moore was offered the first script on spec and Skinn was impressed enough to give him the assignment. Artist David Lloyd had been asked to create a mystery strip in the vein of his Marvel UK hit Night Raven, and independently suggested Moore, with whom he had worked on Doctor Who and Star Wars stories at Marvel UK, as the writer; their collaboration became V for Vendetta.

Laser Eraser and Pressbutton, a science fiction strip about a pair of assassins, featured Axel Pressbutton, a violent cyborg who had previously appeared in underground strips written by "Pedro Henry" (a pseudonym for Steve Moore) and drawn by "Curt Vile" (Alan Moore). At Skinn's insistence, Laser Eraser and Pressbutton featured a female partner, Mysta Mystralis, and was written by Pedro Henry and drawn by Steve Dillon. Under his own name, Steve Moore also wrote the occult adventure Father Shandor, Demon Stalker (continuing the stories from Skinn's House of Hammer magazine), among others. Steve Parkhouse, who had written the Arthurian-themed superhero strip Black Knight for Hulk Weekly, wrote and drew a fantasy adventure called The Spiral Path.

Using the same magazine format Skinn had employed for his earlier House of Hammer and Starburst to reach an older audience, Warrior was distributed nationally through newsagents and was launched to strong sales.[citation needed]

After a few issues Garry Leach bowed out as Marvelman's artist, giving way to Alan Davis. Leach became the magazine's art director, and later drew the Marvelman spin-off as well as Zirk, a lecherous egg-shaped alien spun off from Pressbutton, some of whose stories were drawn by Brian Bolland. After the completion of The Spiral Path, Parkhouse teamed with Alan Moore to create the macabre comedy The Bojeffries Saga, a kind of British working-class Addams Family owing much to Henry Kuttner's Hogben Family. Dez Skinn himself wrote Big Ben, a spin-off character from Marvelman, drawn by Will Simpson. Mick Austin contributed painted covers.

Skinn wanted each strip to form part of a "Warrior Universe" and connect with each other.[citation needed] This never really happened as Skinn intended, although there were some crossover strips, e.g. Big Ben and Warpsmith tied into Marvelman. Grant Morrison's The Liberators was also part of this universe, set in the future of Big Ben's timeline and featuring alien characters in common.

Despite a strong launch and critical acclaim,[citation needed] sales were not strong[citation needed] and for much of its run the magazine was subsidised from the profits of Skinn's comic shop, Quality Comics. Offered to newsagents on a "sale or return" basis, it suffered a high rate of returns.[citation needed] The high level of creator control also led to problems: the second series of Laser Eraser and Pressbutton was never completed because artist Steve Dillon went AWOL, and issues began to turn up late when contributors missed deadlines and fill-in artists could not be commissioned, as the originating artists owned the work. The title had also managed to appeal to a female audience unlike 2000 AD thanks to the inclusion of strong women characters but as later issues became dominated by more sexist material that readership declined.[citation needed] Though primarily a British publication, Warrior also had some distribution in the U.S. and acquired a fan following there.[4]

Marvelman last appeared in Warrior in issue 21. This was ostensibly because, after Quality published a spin-off Marvelman Special featuring stories from the character's original run, Marvel Comics objected that this was a trademark infringement on the better known Marvel brand name. The actual reason was a series of bitter financial disagreements between Skinn and Moore.[3] Other strips were affected by creative disputes, with only V for Vendetta not suffering any gaps in publication. Many of the title's top creators were being offered work from U.S. publishing companies, causing problems in finding new talent.

Warrior ended its run with issue 26 in 1985. Through Mike Friedrich's Star*Reach agency, Skinn signed all the Warrior work (except V for Vendetta) to Pacific Comics. Pacific folded within months, and another American independent publisher, Eclipse Comics, picked them up.

A final "Spring Special" flip book issue was published in #67 of Skinn's Comics International in 1996.

"It did its job. Despite the inevitable disagreements such leads to, it showed what could be done with comics when creators are given ownership of properties," Skinn commented when interviewed about the title.[citation needed]

Uncompleted stories such as Marvelman and V for Vendetta were completed elsewhere.

Stories[]

Stories that featured in Warrior include:

- Axel Pressbutton ("Pedro Henry" and Steve Dillon)

- Big Ben (Dez Skinn and Will Simpson)

- Bogey (Antonio Segura, Dez Skinn and Leopoldo Sanchez)

- The Bojeffries Saga (Alan Moore and Steve Parkhouse)

- The Black Currant (Carl Critchlow)

- Ektryn ("Pedro Henry" and Cam Kennedy)

- Father Shandor (Steve Moore, John Bolton, and John Stokes) — Issues #1–10, 13, 16, 18–21, 23–25 (issues #1–3 reprint material from House of Hammer issues #8, 16, and 21; the rest are original to Warrior)[5]

- The Legend of Prester John (Steve Parkhouse and John Ridgway)

- The Liberators (Grant Morrison and John Ridgway)

- (Paul Neary and Mick Austin)

- Marvelman (Alan Moore, Garry Leach and Alan Davis)

- (Steve Parkhouse, John Ridgway, David Jackson and John Bolton)

- Twilight World (Steve Moore and Jim Baikie)

- V for Vendetta (Alan Moore and David Lloyd)

- (Alan Moore and Garry Leach)

- (Brian Bolland, "Pedro Henry" and Garry Leach)

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Skinn, Dez. "WARRIOR: TAKE ONE," DezSkinn.com. Accessed Jan. 25, 2020.

- ^ Green, Steve. "This Month," The Birmingham Science Fiction Group #147 (Nov. 1983), p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Harvey, Allan (June 2009). "Blood and Sapphires: The Rise and Demise of Marvelman". Back Issue!. TwoMorrows Publishing (34): 69–76.

- ^ Barr, Mike W. (October 2010). "Department of Corrections". Back Issue!. TwoMorrows Publishing (44): 78.

- ^ Skinn, Dez. Response to reader question, Halls of Horror #29 (1984).

Further reading[]

- Khoury, George (2001), Kimota! The Miracleman Companion, TwoMorrows Publishing, ISBN 978-1-893905-11-5

- Khoury, George (2003), The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, TwoMorrows Publishing ISBN 1-893905-24-1

- Warrior at the Grand Comics Database

- Warrior at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

External links[]

- Warrior background on Dez Skinn's site

- Warrior bibliography and interview with Dez Skinn by Richard J. Arndt at Enjolrasworld.com

- British comics titles

- 1982 comics debuts

- 1985 comics endings

- Fantasy comics

- Science fiction comics

- Defunct British comics

- Warrior

- Comics anthologies

- War comics