Western Azerbaijan (political concept)

Western Azerbaijan (Azerbaijani: Qərbi Azərbaycan) is an irredentist political concept that is used in the Republic of Azerbaijan mostly to refer to the territory of the Republic of Armenia. Azerbaijani statements claim that the territory of the modern Armenian republic were lands that once belonged to Azerbaijanis.[1] Its claims are primarily hinged over the contention that the current Armenian territory was under the rule of various Turkic tribes, empires and khanates from the Late Middle Ages until the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) signed after the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828. The concept has received official sanction by the government of Azerbaijan, and has been used by its current president, Ilham Aliyev, who, since around 2010, has made regular reference to "Irevan" (Yerevan), "Göyçə" (Lake Sevan) and "Zangezur" (Syunik) as once and future "Azerbaijani lands".[2] Also, after Aliyev was nominated in 2018 by the New Azerbaijan Party as presidential candidate, he called for "the return of Azerbaijanis" to these lands".[2]

Term, background and usage[]

The term "Western Azerbaijan" was originally a colloquialism used by some Azerbaijani refugees to refer to the Armenian SSR of the Soviet Union.[2] In the late 1990s, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the independent republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan, the term began to assume a more geopolitical meaning "as a revivalist project recovering the history of this population after displacement".[2] As a return to Armenia was never considered to be politically feasible, those Azerbaijani refugees integrated into mainstream Azerbaijani society, with the community fading away over time.[2] However, as the historian and political scientist Laurence Broers explains, the historical geography of an "Azerbaijani palimpsest" underneath the soil of modern Armenia remained alive.[2] From the mid-2000s, the concept of a "Western Azerbaijan" was merged into renewed interest of the Khanates of the Caucasus, in, what Broers explains as "wide-ranging fetishisation" of the Erivan Khanate as a "historically Azerbaijani entity".[2] Within Azerbaijani historiography, the Erivan Khanate has undergone the same type of transformation like the historic entity of Caucasian Albania before it.[2] Azerbaijani historiography regards the Erivan Khanate as an "Azerbaijani state" which was populated by autochtonous Azerbaijani Turks, and its soil is sacralised, as Broers adds, "as the burial ground of semi-mythological figures from the Turkic pantheon".[2] Within the same Azerbaijani historiography, the terms "Azerbaijani Turk" and "Muslim" are used interchangeably, even though contemporary demographic surveys differentiate "Muslims" into Persians, Shia and Sunni Kurds and Turkic tribes.[2]

According to Broers, catalogues of "lost Azerbaijani heritage" portray an array of "Turkic palimpsest beneath almost every monument and religious site in Armenia – whether Christian or Muslim".[2] Additionally, from around 2007, standard maps of Azerbaijan started to show Turkic toponyms printed in red underneath the Armenian ones on the major part of Armenia which it shows.[2] In terms of rhetoric, as Broers narrates, the Azerbaijani palimpsest beneath Armenia "reaches into the future as a prospective territorial claim".[2] The Armenian capital of Yerevan is particularly focused by this narrative; the Yerevan Fortress and Sardar Palace, which had been demolished by the Soviets during their builing of the city, have become "widely disseminated symbols of lost Azerbaijani heritage recalling the fetishised contours of a severed body part".[2] Similarly, Lake Sevan is also often targeted, wherein its referred to by its Azerbaijani name Göyçə.[2]

History[]

The present-day territory of Armenia along with the western part of Azerbaijan, including Nakhchivan were historically part of the Armenian Highlands.[4]

In the Middle Ages, the Oghuz Turkic Seljuks, Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu held sway in the region. Afterward, the area was under the control of the Safavid Empire.

Under the Iranian Safavids, the area that constitutes the bulk of the present-day Republic of Armenia, was organized as the Erivan Province. The Erivan Province also had Nakhchivan as one of its administrative jurisdictions. A number of the Safavid era governors of the Erivan Province were of Turkic origin. Together with the Karabagh province, the Erivan Province comprised Iranian Armenia.[5][6]

Iranian ruler Nader Shah (r. 1736-1747) later established the Erivan Khanate (i.e. province); from then on, together with the smaller Nakchivan Khanate, these two administrative entities constituted Iranian Armenia.[7] In the Erivan Khanate, the Armenian citizens had partial autonomy under the immediate jurisdiction of the melik of Erevan.[8] In the Qajar era, members of the royal Qajar dynasty were appointed as governors of the Erivan khanate, until the Russian occupation in 1828.[9] The heads of the provincial government of the Erivan Khanate were thus directly related to the central ruling dynasty.[10]

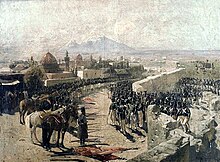

In 1828, per the Treaty of Turkmenchay, Iran was forced to cede the Erivan and Nakhchivan Khanates to the Russians. These two territories, which had constituted Iranian Armenia prior to 1828, were added together by the Russians and then renamed into the "Armenian Oblast".

According to journalist Thomas de Waal, A few residents of Vardanants Street recall a small mosque being demolished in 1990.[11] Geographical names of Turkic origin were changed en masse into Armenian ones,[12] a measure seen by some as a method to erase from popular memory the fact that Muslims had once formed a substantial portion of the local population.[13] According to Husik Ghulyan's study, in the period 2006-2018, more than 7700 Turkic geographic names that existed in the country have been changed and replaced by Armenian names.[14] Those Turkic names were mostly located in areas that previously were heavily populated by Azerbaijanis, namely in Gegharkunik, Kotayk and Vayots Dzor regions and some parts of Syunik and Ararat regions.[14]

Demographic basis[]

Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[15] At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns, Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia.[15] After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians and Muslims in 1604-05,[16] their numbers dwindled even further.

Some 80% of the population of Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[17] As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede Iranian Armenia (which also constituted the present-day Republic of Armenia), to the Russians.[7][18]

After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[19] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[17] Anyhow, it would be only after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, that ethnic Armenians once again established a solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[20] Nevertheless, the city of Yerevan remained having a Muslim majority up to the twentieth century.[20] According to the traveller H. F. B. Lynch, the city of Erivan was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Tatars[a] i.e. Azeris and Persians) in the early 1890s.[8]

According to the Russian census of 1897, a significant population of Azeris still lived in Russian Armenia. They numbered about 300,000 persons or 37.8% in Russia's Erivan Governorate (roughly corresponding to most of present-day central Armenia, the Iğdır Province of Turkey, and Azerbaijan's Nakhchivan exclave, but excluding Syunik and most of northern Armenia). Most lived in rural areas and were engaged in farming and carpet-weaving. They formed the majority in 4 of the governorate's 7 districts (including Igdir and Nakhchivan, which are not part of Armenia today and Sharur-Daralagyoz district which is mostly in Azerbaijan) and were nearly as many as the Armenians in Yerevan (42.6% against 43.2%).[23] At the time, Eastern Armenian cultural life was centered more around the holy city of Echmiadzin, seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[24]

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were 149 Azerbaijani, 91 Kurdish and 81 Armenian villages in Syunik.[25] Traveller Luigi Villari reported in 1905 that in Yerevan the Tatars were generally wealthier than the Armenians, and owned nearly all of the land.[26]

See also[]

- Azerbaijanis in Armenia

- Khanates of the Caucasus

- Erivan Khanate

- History of Azerbaijan

- Whole Azerbaijan

Notes[]

- ^ The term "Tatars", employed by the Russians, referred to Turkish-speaking Muslims (Shia and Sunni) of Transcaucasia.[21] Unlike Armenians and Georgians, the Tatars did not have their own alphabet and used the Perso-Arabic script.[21] After 1918 with the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and "especially during the Soviet era", the Tatar group identified itself as "Azerbaijani".[21] Prior to 1918 the word "Azerbaijan" exclusively referred to the Iranian province of Azarbayjan.[22]

References[]

- ^ "Present-day Armenia located in ancient Azerbaijani lands - Ilham Aliyev". News.Az. October 16, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Broers 2019, p. 117.

- ^ See Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia, Vol. II: From Versailles to London, 1919-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 192, map 4, 526–529. ISBN 0-520-04186-0.

- ^ A. West, Barbara (2008). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Volume 1. Facts on File. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8160-7109-8.

- ^ Bournoutian 2006, p. 213.

- ^ Payaslian 2007, p. 107.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998, pp. 542–551.

- ^ "Iranians, in order to save the rest of eastern Armenia, heavily subsidized the region and appointed a capable governor, Hosein Qoli Khan, to administer it." -- A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present), George Bournoutian, Mazda Publishers (2002), p. 215

- ^ Bournoutian 2004, pp. 519–520.

- ^ Myths and Realities of Karabakh War by Thomas de Waal. Caucasus Reporting Service. CRS No. 177, 1 May 2003. Retrieved 31 July 2008

- ^ (in Russian) Renaming Towns in Armenia to Be Concluded in 2007. Newsarmenia.ru. 22

- ^ Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States by Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras. Cambridge University Press, 1993; p.270 ISBN 0-521-43281-2

- ^ a b Ghulyan, Husik (2020-12-01). "Conceiving homogenous state-space for the nation: the nationalist discourse on autochthony and the politics of place-naming in Armenia". Central Asian Survey. 40 (2): 257–281. doi:10.1080/02634937.2020.1843405. ISSN 0263-4937. S2CID 229436454.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11, 13–14.

- ^ Arakel of Tabriz. The Books of Histories; chapter 4. Quote: "[The Shah] deep inside understood that he would be unable to resist Sinan Pasha, i.e. the Sardar of Jalaloghlu, in a[n open] battle. Therefore he ordered to relocate the whole population of Armenia - Christians, Jews and Muslims alike, to Persia, so that the Ottomans find the country depopulated."

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, p. 14.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Bournoutian, George (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900-1914. Routledge. p. 35 (note 25).

- ^ Bournoutian, George (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900-1914. Routledge. p. xiv.

- ^ Russian Empire Census 1897

- ^ Thomas de Waal. Black Garden: Armenia And Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, p. 74. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- ^ (in Russian) Кавказский календарь на 1900 г., III Отдел. Статист. свед. с. 42-43, Елизаветпольская губерния. Свод статистических данных извлеченных из посемейных списков населения Кавказа., Тифлис, 1888, с.V

- ^ Fire and Sword in the Caucasus by Luigi Villari. London, T. F. Unwin, 1906: p. 267

Sources[]

- Bournoutian, George A. (1980). "The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826-1832". The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bournoutian, George A. (2004). "ḤOSAYNQOLI KHAN SARDĀR-E IRAVĀNI". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 519–520.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2006). A Concise History of the Armenian People (5 ed.). Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. pp. 214–215. ISBN 1-56859-141-1.

- Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1474450522.

- Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. (1998). "EREVAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 542–551.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230608580.

- Geography of Azerbaijan

- Geography of Armenia

- Armenia–Azerbaijan relations

- Armenian Azerbaijanis

- Azerbaijani irredentism