What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

Coordinates: 43°09′22″N 77°36′47″W / 43.1562269°N 77.6129184°W

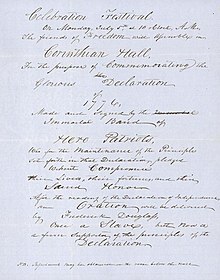

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"[1][2] is the title now given to a speech by Frederick Douglass delivered on July 5, 1852, in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, New York, addressing the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society.[3] The speech is perhaps the most widely known of all of Frederick Douglass' writings save his autobiographies. Many copies of one section of it, beginning in paragraph 32, have been circulated online.[4] Due to this and the variant titles given to it in various places, and the fact that it is called a July Fourth Oration but was actually delivered on July 5, some confusion has arisen about the date and contents of the speech. The speech has since been published under the above title in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One, Vol. 2. (1982) [5]

While referring to the celebrations of the Independence Day in the United States the day before, the speech uses biting irony and bitter rhetoric, and acute textual analysis of the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, and the Christian Bible, to advance a values-based argument against the continued existence of Slavery in the United States.[3] Douglass orates that positive statements about American values, such as liberty, citizenship, and freedom, were an offense to the enslaved population of the United States because of their lack of freedom, liberty, and citizenship. As well, Douglass referred not only to the captivity of enslaved people, but to the merciless exploitation and the cruelty and torture that slaves were subjected to in the United States.[6] Rhetoricians R.L. Heath and D. Waymer called this topic the "paradox of the positive" because it highlights how something positive and meant to be positive can also exclude individuals.[6]

Views expressed in the speech[]

The 4th of July Address, delivered in Corinthian Hall, by Frederick Douglass, is published on good paper, and makes a neat pamphlet of forty pages. The 'Address' may be had at this office, price ten cents, a single copy, or six dollars per hundred.

—Advertisement for the pamphlet of Douglass' speech from the July 12, 1852 edition of Frederick Douglass' Paper (formerly The North Star)

Douglass said that the fathers of the nation were great statesmen, and that the values expressed in the Declaration of Independence were "saving principles", and the "ringbolt of your nations destiny", stating, "stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost." However, he maintained that slaves owed nothing to and had no positive feelings towards the founding of the United States. He faulted America for utter hypocrisy and betrayal of those values in maintaining the institution of slavery.

What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?...What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.[7]

Douglass also stresses the view that slaves and free Americans are equal in nature. He expresses his belief in the speech that he and other slaves are fighting the same fight in terms of wishing to be free that White Americans, the ancestors of the white people he is addressing, fought seventy years earlier.

They were statesmen, patriots, and heroes, and…with them, justice, liberty, and humanity were final; not slavery and oppression.[8]:340

Douglass also says that if the residents of America believe that slaves are "men",[8]:342 they should be treated as such. True Christians, according to Douglass, should not stand idly by while the rights and liberty of others are stripped away.

Douglass denounces the churches for betraying their own biblical and Christian values. He is outraged by the lack of responsibility and indifference towards slavery that many sects have taken around the nation. He says that, if anything, many churches actually stand behind slavery and support the continued existence of the institution. Douglass equates this to being worse than many other things that are banned, in particular, books and plays that are banned for infidelity.

They convert the very name of religion into an engine of tyranny and barbarous cruelty, and serve to confirm more infidels, in this age, than all the infidel writings of Thomas Paine, Voltaire, and Bolingbroke put together have done.[8]:344

Nevertheless, Douglass claims that this can change. The United States does not have to stay the way it is. The country can progress like it has before, transforming from being a colony of a far-away king to an independent nation. Great Britain, and many other countries of that time, had already abolished slavery from its territories. The British accomplished this through religion or more specifically, the church. Because the church stood behind the decision to abolish the selling and buying of human people, so did the rest of the country. Douglass argues that religion is the center of the problem but also the main solution to it.

Douglass believed that slavery could be eliminated with the support of the church, and also with the reexamination of what the Bible was actually saying.

You profess to believe, "that, of one blood, God made all nations of men to dwell on the face of all the earth," and hath commanded all men everywhere to love one another; yet you notoriously hate (and glory in your hatred) all men whose skins are not colored like your own.[8]:345

Douglass wants his audience to realize that they are not living up to their proclaimed beliefs. He talks about how they, being Americans, are proud of their country and their religion and how they rejoice in the name of freedom and liberty and yet they do not offer those things to millions of their country's residents.[8]:345

He employs irony to do a lot of this work. Douglass spends time celebrating the efforts of the founding fathers of America for fighting back against the tyranny of England when he says[9]

Oppression makes a wise man mad. Your fathers were wise men, and if they did not go mad, they became restive under this treatment. They felt themselves the victims of grievous wrongs, wholly incurable in their colonial capacity. With brave men there is always a remedy for oppression. Just here, the idea of a total separation of the colonies from the crown was born! It was a startling idea, much more so, than we, at this distance of time, regard it. The timid and the prudent (as has been intimated) of that day, were, of course, shocked and alarmed by it.

Douglass details the hardships past Americans once endured when they were members of British colonies and validates their feelings of ill treatment. He does all this to show the irony of their inability to sympathize with the Black people they oppressed in cruel ways that the forefathers they valorized never experienced. He validates the feelings of injustice the Founders felt then juxtaposes their experiences with vivid descriptions of the harshness of slavery when he says:[10]

The crack you heard, was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard, was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on. Follow the drove to New Orleans. Attend the auction; see men examined like horses; see the forms of women rudely and brutally exposed to the shocking gaze of American slave-buyers. See this drove sold and separated forever; and never forget the deep, sad sobs that arose from that scattered multitude. Tell me citizens, WHERE, under the sun, you can witness a spectacle more fiendish and shocking. Yet this is but a glance at the American slave-trade, as it exists, at this moment, in the ruling part of the United States.

Essentially, Douglass criticizes his audience's pride for a nation that claims to value freedom though it is composed of people who continuously commit atrocities against Blacks. It is said that America is built on the idea of liberty and freedom, but Douglass tells his audience that more than anything, it is built on inconsistencies and hypocrisies that have been overlooked for so long they appear to be truths. According to Douglass, these inconsistencies have made the United States the object of mockery and often contempt among the various nations of the world.[8]:346 To prove evidence of these inconsistencies, as one historian noted, during the speech Douglass claims that the United States Constitution is an abolitionist document and not a pro-slavery document.[11] Douglass said:[12][13]

Fellow-citizens! there is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon, as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither.

In this respect, Douglass' views converged with that of Abraham Lincoln's[14] in that those politicians who were saying that the Constitution was a justification for their beliefs in regard to slavery were doing so dishonestly.

However, if slavery were abolished and equal rights given to all, that would no longer be the case. In the end, Douglass wants to keep his hope and faith in humanity high. Douglass declares that true freedom can not exist in America if Black people are still enslaved there and is adamant that the end of slavery is near. Knowledge is becoming more readily available, Douglass said, and soon the American people will open their eyes to the atrocities they have been inflicting on their fellow Americans.

Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. It makes its pathway over and under the sea, as well as on the earth.[8]:346

Later views on American independence[]

The speech "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was delivered in the decade preceding the American Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865 and achieved the abolition of slavery. During the Civil War, Douglass said that since Massachusetts had been the first state to join the Patriot cause during the American Revolutionary War, black men should go to Massachusetts to enlist in the Union Army.[15] After the Civil War, Douglass said that "we" had achieved a great thing by gaining American independence during the American Revolutionary War, though he said it was not as great as what was achieved by the Civil War.[16]

Legacy[]

In the United States, the speech is widely taught in history and English classes in high school and college.[3] American studies professor Andrew S. Bibby argues that because many of the editions produced for educational use are abridged, they often misrepresent Douglass's original through omission or editorial focus.[3]

A statue of Douglass erected in Rochester in 2018 was torn down on July 5, 2020—the 168th anniversary of the speech.[17][18] The head of the organization responsible for the memorial speculated that it was vandalized in response to the removal of Confederate monuments in the wake of the George Floyd protests. Though there are no evidence to prove this statement. [19]

Notable readings[]

The speech has been notably performed or read by important figures, including the following:

- James Earl Jones[3]

- Morgan Freeman[3]

- Danny Glover[3]

- Ossie Davis[3]

- Baratunde Thurston[20]

- Five of his descendants[21]

References[]

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1852). Frederick Douglass, Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, July 5th, 1852. Rochester: Lee, Mann &co., 1852. Rochester, NY: Lee, Mann &Co.

- ^ https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/what-to-the-slave-is-the-fourth-of-july/

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Bibby, Andrew S. (July 2, 2014). "'What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?': Frederick Douglass's fiery Independence Day speech is widely read today, but not so widely understood". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ The paragraphing referenced here is taken from an edition of the speech at RhetoricalGoddess

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1982). Blassingame, John W. (ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches Debates, and Interviews. Vol. 2, 1847-54. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 359-387.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heath, Robert L.; Waymer, Damion (2009). "Activist Public Relations and the Paradox of the Positive: A Case Study of Frederick Douglass's Fourth of July Address". Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II: 192–215. ISBN 9781135220877.

- ^ Battistoni, Richard. The American Constitutional Experience: Selected Readings & Supreme Court Opinions, pp. 66-73 (Kendall Hunt, 2000).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Douglass, Frederick (1852). "Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, July 5, 1852". In Harris, Leonard; Pratt, Scott L.; Waters, Anne S. (eds.). American Philosophies: An Anthology. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-631-21002-3.

- ^ ""What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"". Teaching American History. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ ""What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"". Teaching American History. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Colaiaco, James A. (March 24, 2015). Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 9781466892781 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Exceptionalism and the left". Los Angeles Times. December 13, 2010.

- ^ African Americans In Congress: A Documentary History, by Eric Freedman and Stephen A, Jones, 2008, p. 39

- ^ Gorski, Philip (February 6, 2017). American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400885008 – via Google Books.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. Frederick Douglass on Slavery and the Civil War: Selections from His Writings, p. 46 (Dover Publications, 2014): "We can get at the throat of treason and slavery through the State of Massachusetts. She was first in the War of Independence; first to break the chains of her slaves; first to make the black man equal before the law; first to admit colored children to her common schools, and she was first to answer with her blood the alarm cry of the nation, when its capital was menaced by rebels."

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. Autobiographies, p. 765 (Library of America, 1994): "It was a great thing to achieve American Independence when we numbered three millions, but it was a greater thing to save this country from dismemberment and ruin when it numbered thirty millions."

- ^ Schwartz, Matthew S. (July 6, 2020). "Frederick Douglass Statue Torn Down On Anniversary Of Famous Speech". NPR. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Deneen L. (July 6, 2020). "Frederick Douglass statue torn down in Rochester, N.Y., on anniversary of his famous Fourth of July speech". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (July 6, 2020). "Frederick Douglass statue torn down on anniversary of great speech". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

Speaking to WROC, [Carvin] Eison asked: 'Is this some type of retaliation because of the national fever over Confederate monuments right now? Very disappointing, it’s beyond disappointing.'

- ^ Thurston, Baratunde (July 4, 2020) [Recorded July 1, 2016]. Baratunde Delivers USA Co-Founder Frederick Douglass 1852 Speech: 'What To The Slave Is The 4th of July'. Facebook. Directed by Tara Garver Mikhael. Brooklyn Public Library. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "VIDEO: Frederick Douglass' Descendants Deliver His 'Fourth Of July' Speech". NPR.org. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

Further reading[]

- Bizzell, Patricia (1997-02-01). "The 4th of July and the 22nd of December: The Function of Cultural Archives in Persuasion, as Shown by Frederick Douglass and William Apess". College Composition and Communication. 48 (1): 44–60. doi:10.2307/358770. ISSN 0010-096X. JSTOR 358770.

- Douglass, Frederick. A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. 1845.

- Douglass, Frederick, ed. Stauffer, John. Random House. 2003. My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I - Life as a Slave, Part II - Life as a Freeman, with an introduction by James McCune Smith. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan. 1855.

- Gates, Jr. Henry Louis, ed. Frederick Douglass, Autobiography. New York: Library of America. 1994.

- Oakes, James. The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. 2007.

External links[]

- Frederick Douglass' Descendants Deliver His 'Fourth of July' Speech (video)

- First edition of the publication of Douglass' speech

- Discussion of the pamphlet from The Public Domain Review

What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? public domain audiobook at LibriVox

What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Speeches by Frederick Douglass

- 1852 speeches

- Slavery in the United States

- History of Rochester, New York

- Independence Day (United States)

- 1852 in New York (state)

- Abolitionism in the United States