White Croats

White Croats (Croatian: Bijeli Hrvati; Polish: Biali Chorwaci; Czech: Bílí Chorvati; Ukrainian: Білі хорвати, romanized: Bili khorvaty), or simply known as Croats, were a group of Early Slavic tribes who lived among other West and East Slavic tribes in the area of modern-day Lesser Poland, Galicia (north of Carpathian Mountains), Western Ukraine, and Northeastern Bohemia.[1][2][3] They were documented primarily by foreign medieval authors and managed to preserve their ethnic name until the early 20th century, primarily in Lesser Poland. It is considered that they were assimilated into Czech, Polish and Ukrainian ethnos,[4] and are one of the predecessors of the Rusyn people.[5][6] In the 7th century, some White Croats migrated from their homeland, White Croatia, to the territory of modern-day Croatia in Southeast Europe along the Adriatic Sea, forming the ancestors of the South Slavic ethnic group of Croats.

Etymology[]

It is generally believed that the Croatian ethnonym - Hrvat, Horvat and Harvat - etymologically is not of Slavic origin, but a borrowing from Iranian languages.[7][8][9][10][11][12] According to the most plausible theory by Max Vasmer, it derives from *(fšu-)haurvatā- (cattle guardian),[13][14][15][16][17] more correctly Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector").[18]

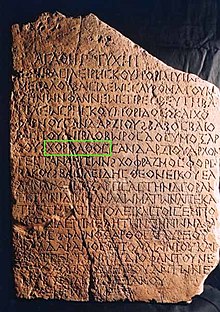

It is considered that the ethnonym is first attested in anthroponyms Horoúathos, Horoáthos, and Horóathos on the two Tanais Tablets, found in the Greek colony of Tanais at the shores of Sea of Azov in the late 2nd and early 3rd century AD, at the time when the colony was surrounded by Iranian-speaking Sarmatians.[19] However, acceptance of any non-Slavic etymology is problematic because it implies an ethnogenesis relationship with the specific ethnic group.[20] There is no mention of an Iranian tribe named as Horoat in the historical sources, but it was not uncommon for Slavic tribes to get their tribal names from anthroponyms of their forefathers and chiefs of the tribe, like in the case of Czechs, Dulebes, Radimichs, and Vyatichi.[21]

Any mention of the Croats before the 9th century is uncertain, and there were several loose attempts at tracing; Struhates, Auhates, and Krobyzoi by Herodotus,[22] Horites by Orosius in 418 AD,[22][23] and the Harus (original form Hrws,[24] some read Hrwts;[25] Hros, Hrus) at the Sea of Azov, near the mythical Amazons,[26] mentioned by Zacharias Rhetor in 550 AD.[22][24] The Hros some relate to the ethnonym of the Rus' people.[24][27] The distribution of the Croatian ethnonym in the form of toponyms in later centuries is considered to be hardly accidental because it is related with Slavic migrations to Central and South Europe.[28]

The epithet "white" for the Croats and their homeland is related to the use of colors for cardinal directions among Eurasian people. That is, it meant "Western Croats",[10][29] or "Northern Croats",[30] in comparison to lands where they lived before. The epithet "great" signified an "old, ancient" or "former" homeland,[31] for the Croats when they were new arrivals in the Roman province of Dalmatia.[32][33][34]

Although the early medieval Croatian tribes in the scholarship are often called as White Croats, there's a scholarly dispute whether it is a correct term as some scholars differentiate the tribes according to separate regions and that the term implies only the medieval Croats who lived in Central Europe.[35][36][37][38]

Origin[]

The first Iranian tribes who lived on the shores of the Sea of Azov were Scythians, who arrived there c. 7th century BCE.[39] Around the 6th century BCE the Sarmatians began their migration westwards, gradually subordinating the Scythians by the 2nd-century BCE.[40] During this period there was substantial cultural and linguistic contact between the Early Slavs and Iranians,[41][42] and in this environment were formed the Antes.[43] Antes were Slavic people who lived in that area and to the West between Dniester and Dnieper from the 4th until the 7th century.[44][45] It is thought that the Croats were part of the Antes tribal polity who migrated to Galicia in the 3rd-4th century, under pressure by invading Huns and Goths.[46][47][48]

It is argued that they lived there until the Antes were attacked by the Pannonian Avars in 560, and the polity was finally destroyed in 602 by the same Avars.[49][50] This resulted with breaking Croatian tribal unity into several groups, in Prykarpattia (Western Ukraine), in Silesia and the lower course of the Vistula river (Lesser Poland), and Eastern Czech Republic.[51] The early Croats' migration to Dalmatia (during the reign of Heraclius 610-641) can thus be seen as a continuation of the previous war between the Antes and Avars.[52][50] In a similar fashion, in his synthesis of works on Early Croats, regardless of Iranian or Slavic etymology of their name, Henryk Łowmiański concluded that the tribe was formed by the end of the 3rd and not later than the 5th century in Lesser Poland,[53] during the peak of the Huns and their leader Attila.[54]

There is a dispute among Slavic scholars as to whether the Croats were of Irano-Alanic, West Slavic, or East Slavic origin.[55][56][57][58] Some scholars linguistically and archaeologically also draw parallels between Croats and Slavs with the Carpi, who previously lived in the territory of Carpathian Mountains.[59][60][61] Whether the early Croats were Slavs who had taken a name of Iranian origin, or whether they were ruled by a Sarmatian elite and were Slavicized Sarmatians, cannot be resolved, but is considered that they arrived as Slavic people when entered the Balkans. The possibility of Irano-Sarmatian elements among, or influences upon, early Croatian ethnogenesis cannot be entirely excluded.[3][8][62][63][64][65] The dispute on affiliation with West and East Slavs is also disputed on linguistic grounds because the South Slavs are linguistically closer to East Slavs.[66][67][68]

History[]

Middle Ages[]

Nestor the Chronicler in his Primary Chronicle (12th century) mentions the White Croats, calling them Horvate Belii or Hrovate Belii, the name depending upon which manuscript of his is referred to:

"Over a long period the Slavs settled beside the Danube, where the Hungarian and Bulgarian lands now lie. From among these Slavs, parties scattered throughout the country and were known by appropriate names, according to the places where they settled. Thus some came and settled by the river Morava, and were named Moravians, while others were called Czechs. Among these same Slavs are included the White Croats, the Serbs, and the Carinthians. For when the Vlakhs (Romans) attacked the Danubian Slavs, settled among them, and did them violence, the latter came and made their homes by the Vistula, and were then called Lyakhs. Of these same Lyakhs some were called Polyanians, some Lutichians, some Mazovians, and still others Pomorians".[69]

Most what is known about the early history of White Croats comes from the work by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio (10th century).[70] In the 30th chapter, "The Story of the Province of Dalmatia" Constantine wrote:

"The Croats at that time were dwelling beyond Bagibareia, where the Belocroats are now. From them split off a family, namely of five brothers, Kloukas and Lobelos and Kosentzis and Mouchlo and Chrobatos, and two sisters, Touga and Bouga, who came with their folk to Dalmatia and found this land under the rule of the Avars. After they had fought one another for some years, the Croats prevailed and killed some of the Avars and the remainder they compelled to be subject to them... The rest of the Croats stayed over near Francia, and are now called the Belocroats, that is, the White Croats, and have their own archon; they are subject to Otto, the great king of Francia, which is also Saxony, and are unbaptized, and intermarry and are friendly with the Turks. From the Croats who came to Dalmatia, a part split off and took rule of Illyricum and Pannonia. They too had an independent archon, who would maintain friendly contact, though through envoys only, with the archon of Croatia... From that time they remained independent and autonomous, and they requested holy baptism from Rome, and bishops were sent and baptized them in the time of their Archon Porinos".[71]

In the previous 13th chapter which described the Hungarian neighbors Franks to the West, Pechenegs to the North, and Moravians to the South, it is also mentioned that "on the other side of the mountains, the Croats are neighboring the Turks", however as are mentioned Pechenegs to the North while in the 40th century the Croats are mentioned as the Southern neighbors of the Hungarians, the account is of uncertain meaning,[72] but most probably referring to Croats living "on the other side" of Carpathian Mountains.[73] From the 30th chapter can be observed that the Croats lived "beyond Bavaria" in the sense Eastern of it because the source was of Western origin.[74] They could have been the neighbors of the Franks as early as 846 or 869 when Bohemia was under the control of Eastern Francia. Otto I ruled the Moravians only from 950, and the White Croats were also part of the Moravian state, at least from 929.[75] György Györffy argued that the White Croats were allies of the Hungarians (Turks).[76] A similar story to the 30th chapter is mentioned in the work by Thomas the Archdeacon, Historia Salonitana (13th century), where he recounts how seven or eight tribes of nobles, who he called Lingones, arrived from Poland and settled in Croatia under Totila's leadership.[77] According to the Archdeacon, they were called Goths, but also Slavs, depending on the personal names of those who came from Poland or the Czech lands.[78] Some scholars consider Lingones to be a distortion of the name for the Polish tribe of Lendians.[79] The reliability to the claim adds the recorded oral tradition of Michael of Zahumlje from DAI that his family originates from the unbaptized inhabitants of the river Vistula called as Litziki,[80] identified with Widukind's Licicaviki, also referring to the Lendians (Lyakhs).[81][82] According to Tibor Živković, the area of the Vistula where the ancestors of Michael of Zahumlje originate was the place where White Croats would be expected.[83] In the 31st chapter, "Of the Croats and of the Country They Now Dwell in" Constantine wrote:

"These same Croats arrived as refugees to the emperor of the Romaioi Heraclius before the Serbs came as refugees to the same Emperor Heraclius, at that time when the Avars had fought and expelled from those parts the Romani... Now, by the command of the Emperor Heraclius, these same Croats fought and expelled the Avars from those parts, and, by mandate of Heraclius the emperor they settled down in that same country of the Avars, where they now dwell. These same Croats had the father of Porga for their archon at that time... (It should be known) that ancient Croatia, also called "white", is still unbaptized to this day, as are also its neighboring Serbs. They muster fewer horsemen as well as fewer foot than baptized Croatia, because they are constantly plundered by the Franks and Turks and Pechenegs. Nor do they have either sagēnai or kondourai or merchant ships, because they live far away from sea; it takes 30 days of travel from the place where they live to the sea. The sea to which they come down to after 30 days, is that which is called dark".[84]

According to the 31st chapter, the Pechenegs and Hungarians were neighbors of the White Croats to the East in the second half of the 9th century. In that time Franks plundered Moravia, and White Croatia was probably a part of the Great Moravia.[85] It is notable that in both chapters they are noted to be "unbaptized" Pagans, a description only additionally used for the Moravians and White Serbs. Such an information probably came from an Eastern source because particular religious affiliation was of interest to the Khazars as well as to Arabian historians and explorers who carefully recorded them.[86] Some scholars believe this is a reference to the Baltic Sea, however, more probable is a reference to the Black Sea because in DAI there's no reference to the Baltic Sea, the chapter has information usually found in 10th century Arabian sources like of Al-Masudi, the Black Sea was of more interest to the Eastern merchants and Byzantine Empire, its Persian name "Dark Sea" (axšaēna-) was already well known.[87][88]

Alfred the Great in his Geography of Europe (888–893) relying on Orosius, recorded that, "To the north-east of the Moravians are the Dalamensae; east of the Dalamensians are the Horithi (Choroti, Choriti;[89] Croats), and north of the Dalamensians are the Servians (Serbs); to the west also are the Silesians. To the north of the Horiti is Mazovia, and north of Mazovia are the Sarmatians, as far as the Riphean Mountains".[90] The initial North-East position some considered to be probably wrongly transcribed, as a North-West position agrees with other sources on the location of the Croats on the Oder and Vistula Rivers.[91] However, according to research of Richard Ekblom, Gerard Labuda, and Łowmiański the issue with positioning is present for Scandinavia while the data is "strikingly correct" for the continent.[92] According Łowmiański, with the fact that Frankish chronicles do not mention Croats although they should be near them per DAI, indicates main part of the Croats was located more to the East, roughly in Lesser Poland (up to Moravian Gate) where are usually placed tribes of Vistulans and Lendians who, according to Łowmiański and Tadeusz Lehr-Spławiński, most probably were tribes of Croats after happened a division of the Croatian tribal alliance in the 7th century.[66][93][94]

Croats seemingly were not recorded by the Bavarian Geographer (9th century), however, some scholars assumed that the unknown Sittici ("a region with many peoples and heavily fortified cities") and Stadici ("an infinite population with 516 gords") were part of the Carpathian Croats tribal polity,[95] or that the Croats were part of these unknown tribal designations in Prykarpattia.[96][97] Others saw Lendizi (98), Vuislane, Sleenzane (50), Fraganeo (40; Prague[10][98]), Lupiglaa (30 gords), Opolini (20), and Golensizi (5) as possible tribes of Croats.[99][100][30] Lehr-Spławiński, Łowmiański and others concluded that Vistulans and Lendians because of their mention and described location in different sources were tribes behind which were hidden Croats.[66][101]

More detailed information is given by Arabian historians and explorers. Ahmad ibn Rustah from the beginning of the 10th century recounts that the land of Pechenegs is ten days away from the Slavs and that the city in which lives Swntblk is called ʒ-r-wāb (Džervab > Hrwat), where every month Slavs do three-day long trade fair.[102] Swntblk is called "king of kings", has riding horses, sturdy armor, eats mare's milk, and is more important than Subanj (considered Slavic title župan), who is his deputy.[103] In work by Abu Saʿīd Gardēzī (11th century) the city is also mentioned as ʒ(h)-rāwat,[104] or Džarvat,[105] and as Hadrat by Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi (11th century).[105] In the same way, 10th century Arab historian Al-Masudi in his work The Meadows of Gold mentioned Harwātin or Khurwātīn between Moravians, Chezchs and Saxons.[106][107][108] Abraham ben Jacob in the same century probably has the only Iranian form of the name which is closest to the Vasmer's reconstructed form, hajrawās or hīrwās.[109] The Persian geography book Hudud al-'Alam (10th century), which has information from 9th century, in the area of Slavs mentioned their two capital cities, Wabnit (actually Wāntit, considered as reference to Vyatichi,[110] or Antes[102]), the first city East of Slavs, and Hurdāb (Khurdāb), a big city where ruler S.mūt-swyt resides, located below the mountains (probably Carpathians) on river Rūtā (most probably Prut), which springs from the mountains and is on the frontier between Pechenegs, Hungarians, and Kievan Rus'.[111][112][105] In the chronicles of the time word šahr meant "country, state, city" - thus Hurdāb represented Croatia.[104][113] It was a common practice to call a whole region and country by the capital or well-known city, as well a city by the tribal name, especially if was on the periphery where the first contacts of merchants and researchers took place.[114] Although it is generally accepted that Swntblk refers to Svatopluk I of Moravia (870–894), it was puzzling that the country in which he lived and ruled over was called by the sources as Croatia.[115] Most probable reason for the use of the Croatian name in the East among Arabs is due to trade routes which passed through the lands of Buzhans, Lendians and Vistulans connecting the city of Kraków with the city of Prague, implying they were partly dependent to the rule of Svatopluk I. These facts exclude the possibility of referring to Croats in Bohemia, but also on river Dniester in Ukraine, clearly placing them in Lesser Poland on the territory of Lendians and Vistulans.[116] George Vernadsky also considered that the details on the king's custom of life is an evidence of Alanic and Eurasian nomadic origin of the ruling caste among those Slavs.[103]

In the Hebrew book Josippon (10th century) are listed four Slavic ethnic names from Venice to Saxony; Mwr.wh (Moravians), Krw.tj (Croats), Swrbjn (Sorbs), Lwcnj (Lučané or Lusatians).[117][118][119] Since the Croats are placed between Moravians and Serbs it identified the Croatian realm with the Duchy of Bohemia.[118]

Nestor described how many East Slavic tribes of "...the Polyanians, the Derevlians, the Severians, the Radimichians, and the Croats lived at peace".[120] In 904–907, "Leaving Igor (914–945) in Kiev, Oleg (879–912) attacked the Greeks. He took with him a multitude of Varangians, Slavs, Chuds, Krivichians, Merians, Polyanians, Severians, Derevlians, Radimichians, Croats, Dulebians, and Tivercians, who are pagans. All these tribes are known as Great Scythia by the Greeks. With this entire force, Oleg sallied forth by horse and by ship, and the number of his vessels was two thousand".[121] The list indicates that the closest tribal neighbours were Dulebes-Volhynians,[122][123] The fact no Lechitic tribe was part of Oleg's conquest it is more probable that those Croats were located on river Dniester rather than Vistula.[124] After Vladimir the Great (980–1015) conquered several Slavic tribes and cities to the West,[56] in 992 he "attacked the Croats. When he had returned from the Croatian War, the Pechenegs arrived on the opposite side of the Dnieper".[125] Since then those Croats became part of Kievan Rus and are not mentioned anymore in that territory.[126][56] It seems that Croatian tribes who lived in the area of Bukovina and Galicia were conquered because inhibited Kievan Rus free access to the Vistula valley trade route,[127] and did not want to submit to Kievan centralism and accept Christianity.[128] After the attack on Croats and Polish marches, Vladimir the Great expanded his realm on the territory of which would be known as Principality of Volhynia and Principality of Halych.[129][130][131][132]

To the upper accounts by the historians were related the Vladimir the Great's conquest of the Cherven Cities in 981, and Annales Hildesheimenses note that Vladimir threatened to attack the Duke of Poland, Bolesław I the Brave (992 to 1025), in 992.[133] Polish chronicler Wincenty Kadłubek in his Chronica Polonorum (12-13th century) recounted that Bolesław I the Brave conquered some "Hunnos seu Hungaros, Cravatios et Mardos, gentem validam, suo mancipavit imperio".[126][134] The occurrence of the Croatian name among the people, and the fact during the period of Bolesław I the Brave the Polish realm expanded to the territory later-known as Lesser Poland, indicates that the mentioned Croats most probably lived on the territory of Lesser Poland.[135][136]

According to 10th century First Old Slavonic Legend about Wenceslaus I, Duke of Bohemia, after his murder in 929 or 935 which ordered his brother Boleslaus I,[137] their mother Drahomíra fled in exile to Xorvaty.[138][139][140] This is the first local account of the Croatian name in Slavic language.[141] While some considered that those Croats lived near Prague,[142][140] others noted that in the case of noble and royal fugitives tried to find security as distant as possible, indicating these Croats probably were located more to the East around Vistula valley.[143][144] There were also some attempts to relate with Croats an anonymous neighbor ruler (vicinus subregulus) who was unsuccessfully helped by Saxons and Thuringians at war against Boleslaus I, but the evidence is inconclusive.[145] The Prague Charter from 1086 AD but with data from 973 mentions that on the Northeastern frontier of the Prague diocese lived "Psouane, Chrouati et altera Chrowati, Zlasane...".[146] It is very rare that on a small territory lived two tribes of the same name, indicating that the Crouati were probably settled East of Zlicans and West of Moravians having a territory around the Elbe river, while the other Chrowati were present in Silesia or along the Upper Vistula in Poland because the diocese expanded up to Kraków.[147][148][149] The Eastern part of the diocese territory was part of the Moravian expansion in the 9th and Bohemian expansion in the 10th century.[150] Some scholars located these Czech Croats within the territory of present-day Chrudim, Hradec Králové, Libice and Kłodzko.[151][152] Vach argued that they had the most developed techniques of building fortifications among the Czech Slavs.[153] Many scholars consider that the Slavník dynasty, who competed with the Přemyslid dynasty for control over Bohemia and eventually succumbed to them, was of White Croat origin.[154][155][98] After the Slavník dynasty's main Gord (fortified settlement) Libice was destroyed in 995, the Croats aren't mentioned anymore in that territory.[156]

Thietmar of Merseburg recorded in 981 toponym Chrvuati vicus (also later recorded in 11th-14th century), which is present-day Großkorbetha, between Halle and Merseburg in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.[157] The Chruuati (901) and Chruuati (981) near Halle.[158] In charter by Henry II is recorded Chruazzis (1012), by Henry III as Churbate (1055), by Henry IV as Grawat (also Curewate, 1086). This settlement today is Korbetha on river Saale, near Weißenfels.[157]

In the 10th-12th centuries Croatian name can be often found in the territory of March and Duchy of Carinthia,[159] as well March and Duchy of Styria.[160] In 954, Otto I in his charter mentions župa Croat - "hobas duas proorietatis nostrae in loco Zuric as in pago Crouuati et in ministerio Hartuuigi",[161] and again in 961 pago Crauuati.[162] The pago Chruuat is also mentioned by Otto II (979), and pago Croudi by Otto III.[163]

Legends[]

According to Czech and Polish chronicles, the legendary Lech and Czech came from (White) Croatia.[156] The Chronicle of Dalimil (14th century) recounts "V srbském jazyku jest země, jiežto Charvaty jest imě; v téj zemi bieše Lech, jemužto jmě bieše Čech".[156] Alois Jirásek recounted as "Za Tatrami, v rovinách při řece Visle rozkládala se od nepaměti charvátská země, část prvotní veliké vlasti slovanské" (Behind the Tatra Mountains, in the plains of the river Vistula, stretched from immemorial time Charvátská country (White Croatia), the initial part of the great Slavic homeland), and V té charvátské zemi bytovala četná plemena, příbuzná jazykem, mravy, způsobem života (In Charvátská existed numerous tribes, related by language, manners, and way of life).[164] Dušan Třeštík noted that the chronicle tells Czech came with six brothers from Croatia which once again indicates seven chiefs/tribes like in the Croatian origo gentis legend from the 30th chapter of De Administrando Imperio.[165] It is considered that the chronicle refers to the Carpathian Croatia.[166]

One of the legendary figures Kyi, Shchek and Khoryv who founded Kiev, brother Khoryv or Horiv, and its oronym Khorevytsia, is often related to the Croatian ethnonym.[167][168][169] This legend, recorded by Nestor, has similar Armenian transcript from the 7th-8th century, in which Horiv is mentioned as Horean.[170] Paščenko related his name, beside to the Croatian ethnonym, to solar deity Hors.[169] Near Kiev there's a stream where previously existed large homonymous village Horvatka or Hrovatka (destroyed in the time of Joseph Stalin), which flows into Stuhna River.[171] In the vicinity are parts of the Serpent's Wall.[172]

Some scholars consider that Croats could have been mentioned in the Old English and Nordic epic poems, like the verse in the Old English poem Widsith (10th century), which is similar to the one in Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks (13th century), where prior the battle between Goths and Huns, Heidrek died in Harvaða fjöllum (Carpathian Mountains[173][174]) which is sometimes translated as "beneath the mountains of Harvathi", considered somewhere beneath Carpathian Mountains near river Dnieper.[175][176][177][178] Lewicki argued that Anglo-Saxons, as in the case of Alfred the Great where called Croats Horithi, often distorted foreign Slavic names.[179]

The legendary Czech hermit from the 9th century, Svatý Ivan, is mentioned as the son of certain king Gestimul or Gostimysl, who according to the Czech chronicles descended from the Croats or Obotrites.[180]

Modern age[]

Polish writer Kazimierz Władysław Wóycicki released work Pieśni ludu Białochrobatów, Mazurów i Rusi z nad Bugu in 1836.[181] In 1861, in the statistical data about population in Volhynia governorship released by Mikhail Lebedkin, were counted Horvati with 17,228 people.[182][108] According to United States Congress Joint Immigration Commission which ended in 1911, Polish immigrants to the United States born in around Kraków reportedly declared themselves as Bielochrovat (i.e. White Croat), which with Krakus and Crakowiak/Cracovinian was "names applying to subdivisions of the Poles".[183][184][185]

The Northern Croats contributed and assimilated into Czech, Polish and Ukrainian ethnos.[28][4][186][187] They are considered as the predecessors of the Rusyns,[5][6][188][189] specifically Dolinyans,[190] Boykos,[191][192] Hutsuls,[193][194] and Lemkos.[195][196][197]

Migration to Croatia[]

Early Slavs, especially Sclaveni and Antae, including the White Croats, invaded and settled the Southeastern Europe since the 6th and 7th century.[198] It is considered that the Czech-Polish Croatian tribes were related to the Croatian tribes from Zakarpattia and Prykarpattia in Ukraine,[51][199] and that they became separated during the migration period, at least by the end of the 6th and early 7th century or earlier,[54][66] and seemingly formed one large Proto-Slavic tribe or tribal alliance.[28][200] However, the same ethnic name does not necessarily mean all the tribes had the same origin.[201][202] Their exact place of migration is uncertain, while some scholars considered it to be around Bohemia and Polabia along a Western route through the Moravian Gate, other argued to be in Lesser Poland and Western Ukraine according to historical-archaeological and linguistical data about the main movement of the Avars and Slavs,[203][204] and that "served as a direct link between Eastern and Southern Slavs".[66][191]

There exist several hypotheses on the date and historical context of the migration to the Adriatic Sea, most often being related to the Pannonian Avars activity in late 6th and early 7th century.[205][206] It is considered that the uprising happened after failed Siege of Constantinople (626),[207][208] in the period of the Slavic uprising led by Samo against the Avars in 632,[209][210] or 635-641 when the Avars were defeated by Kubrat of the Bulgars, which are also interpreted as revolts when were already settled.[211] As the Avars were enemies of the Byzantine Empire the involvement of Emperor Heraclius on the side of Croats cannot be entirely excluded.[208][212] It is also theorized that the migration of the Croatian tribes in the 7th century was the second and final Slavic migratory wave to the Balkans,[209][210][57] which is related to the thesis by Bogo Grafenauer about the double migration of Slavs.[213][214] According to this thesis, although it is possible that some Croatian tribes were present among Slavs in the first Slavic-Avar wave in the 6th century, it is argued that the Croatian migration, seen as of a warrior group, in the second wave probably was not equally numerous to make a significant common-linguistical influence into already present Slavs and natives,[66][213][210][57] while others considered they arrived in a significantly larger number.[215] However the thesis on dual division and migration is criticized for being unnatural and improbable.[216]

On the basis of archaeological data between the 7th and 9th century, it is considered that the dating to the 7th century is generally reliable.[217] Zdenko Vinski and V. V. Sedov supported it by the rare findings of objects and ceramics of the first small group of Slavs of the Prague-Korchak culture dated to the end of 6th and beginning of the 7th century, then of the most numerous and second group of Slavs (Antes) of the Prague-Penkovka culture with artifacts of Martinovka culture, while the related archaeological findings from the 8th-9th century indicate social-political stabilization and stratification.[218][219] Another group of historians and archaeologists, like Lujo Margetić and Ante Milošević, argued late 8th-century migration as Frankish vassals during the Frank-Avar war (see Avar March), but it does not have enough evidence,[220] it's not supported in written sources,[204] and is not usually accepted.[221] In the territory of present-day Croatia they gradually assimilated with the Pre-Slavic population as archaeological data does indicate some continuity of late antiquity population who mostly withdrew to the mountains, coastal cities and islands.[222][223] However, the size and influence of the autochthonous population on the ethnogenesis is disputed depending on the interpretation of the archaeological data, considering them as a minority with some cultural influence or as a majority who outnumbered the Slavs.[224]

Archeology[]

According to research by Sedov, all early mentions of Croatian ethnonym are in the areas where ceramics of Prague-Penkovka culture were found. It originated in the area between Dniester and Dnieper, and later expanded to the West and South, and its bearers were the Antes tribes.[225][226] A. V. Majorov criticized Sedov's consideration, who almost exclusively related the Croats with Penkovka culture and the Antes, because the territory the Croats inhabited in the middle and upper Dniester and the upper Vistula was part of Prague-Korchak culture related to Sclaveni which was characteristic for the Kurgan-type of burial which was also found in the upper Elbe territory where presumably lived the Czech Croats.[227] They were representatives of both these archaeological cultures and possibly formed before them at the least late 4th or during the 5th century in the area of the intertwining of these cultures around the Dniester basin.[228] It is considered that the Carpathian Croats later between 7th and 10th century were part of the Luka-Raikovets culture, which developed from Prague-Korchak culture, and was characteristic for East Slavic tribes, besides Croats, including Buzhans, Drevlians, Polans, Tivertsi, Ulichs and Volhynians.[229][230][231][232]

By the 7th century the Croats had established and fortified Horods (Gord), which became a commerce and trade centers.[56] Galicia was an important geographical location because it connected via an overland route Kiev in the East with Kraków, Buda, Prague and other cities in the West, as well as northwest to the Baltic Sea and southeast to the Black Sea.[56] Along these routes were founded the settlements of Przemyśl, Zvenyhorod, Terebovlia, Halych, and Uzhhorod, of which the last was ruled by a mythical ruler Laborec.[56][5]

Archaeological excavations held between 1981 and 1995 which researched Early Middle Age Gords in Prykarpattia and Western Podolia dated between 9th-11th century found that fortified Gords with a range of 0.2 ha made 65%, those of 2 ha 20%, and more than 2 ha 15% in that region.[233] There were more than 35 Gords, including big Gords like Plisnesk, Stilsko, Revno, Lukovyshche, Roztochchya, Zhydachiv, Kotorin complex, Klyuchi, Stuponica, Krylos, Pidhorodyshche, Terebovlia, Halych, Przemyśl, Hanachivka, Solonsko among others.[234][235][236] Only 12 of them survived until the 14th century.[237] UNESCO in its inclusion of Wooden tserkvas of the Carpathian region in Poland and Ukraine also mentions two large gords at the villages of Pidhoroddya and Lykovyshche near Rohatyn dated between 6th and 8th century and identified with the White Croats.[195]

To the White Croats are attributed two Gords of unusually big dimensions and each of them could inhabit tens of thousands of people - Plisnesk with a surface of 450 ha, including a fortress with a pagan center, surrounded by seven long and complex lines of protection, several smaller settlements in the near vicinity, burial mounds and else,[236][238] located near village Pidhirtsi and since 2015 regionally protected as a Historic and Cultural Reserve "Ancient Plisnesk";[239] and Stilsko with a surface of 250 ha, including a fortress of 15 ha, defensive line of 10 km,[240] located on river Kolodnitsa (connected to most important river in the region, Dniester[241]) between current village Stilsko and Lviv.[60][242] In the vicinity of Stilsko were also found some of the only examples of a pre-Christian period cult building among Slavs,[243][244] for one of which Korčinski assumed a possible connection with the medieval descriptions of a temple dedicated to the deity Hors.[60][245] Until 2008 near Stilsko have been found more than 50 settlements of open type dated between 8th-10th century,[246] as well around 200 burial mounds.[247] It indicates a high economic, demographic, defense and political organization in the territory of White Croats,[248][236] with strong polis-like states in the proto-state of Great Croatia.[236][238][249] Stilsko, Plisnesk, and Halych are argued to have been capitals of Eastern (Carpathian) Croats.[241][236][249] According to archaeological material the two Gords and many other settlements by the end of the 10th and beginning of the 11th century temporary ceased to exist with the extensive fire traces interpreted as evidence of the "Croatian War" by the Vladimir the Great in the late 10th century.[250][236][238] It had a devastating effect on the administrative division and population of Galicia (Great Croatia), ultimately stopping their process of becoming a state.[249]

Excavations of many Slavic Kurgans and tombs in the Carpathian Mountains in the 1930s and 1960s were also attributed to the White Croats.[251] Compared to other East Slavic tribes, the area of the Croats stands out because of very present tiled tombs,[252] and in the 11th and 13th century their appearance in Western Dnieper region is attributed to the Croats, and sometimes also Tivertsi,[253] and Ulichs.[254] In the territory of Czech Republic, a significant number of graves with kurgans dated 8th-10th century have been found around the Elbe river where was the presumed territory by the White Croats and Zlicans, as well among Dulebes in the South, and Moravians in the East.[255]

Religion[]

Croatian tribes were like other Slavs polytheists - pagans.[256] Their worldview intertwined with worship of power and war, to which raised places of worship, and demolished those of others.[257] These worships were in contrast to Christianity, and consequently in conflict when Christianism became official religion among the Slavs.[258] The White Croats at the earliest historical sources are mentioned as pagans, and they were similar to the inhabitants of Kievan Rus' who also received Christianity late (988).[259] Slavs often related places of worship with the natural environment, like hills, forests, and water.[260] According to Nestor, Vladimir the Great in 980 raised on a hill near his fort pantheon of Slavic gods; Perun, Hors, Dažbog, Stribog, Simargl, and Mokosh,[128] but as he converted to Christianity in 988 one of the probable reasons Vladimir attacked Croats in 992 was because they didn't want to abandon their old beliefs and accept Christianity.[128] Some scholars derived Croatian ethnonym from the Iranian word for Sun - Hvare-khshaeta, which is also an Iranian solar deity.[261][262] Paščenko argued possibility that in the ethnonym of the Croats could be seen archaic religion and mythology - the worship of the Slavic solar deity Hors (Sun, heavenly fire, force, war[263]), which is of Iranian origin.[264] According to Radoslav Katičić, Vitomir Belaj and others research, upon arrival to present-day Croatia, the pagan Slavic customs, folklore, and toponyms related to Perun, Mokosh and Veles were preserved much longer than previously thought although Adriatic Croats were Christianized by the 9th century.[265]

Origo gentis and etymology[]

The origo gentis about five brothers and two sisters who came with their folk to Dalmatia, recorded in Constantine VII's work De Administrando Imperio, was probably part of an oral tradition,[57] which contradicts the role of Heraclius in the arrival of Croats to Dalmatia.[266] It is similar to other medieval origo gentis stories (see for e.g. Origo Gentis Langobardorum),[266] and some consider it has the same source as the story of Bulgars recorded by Theophanes the Confessor in which the Bulgars subjugated Seven Slavic tribes,[267] and similarly, Thomas the Archdeacon in his work Historia Salonitana mentions that seven or eight tribes of nobles, who he called Lingones, arrived from Lesser Poland and settled in Croatia under Totila's leadership,[77][165] as well parallels in Herodotus account about five men and two maidens of the Hyperboreans.[268] In Archdeacon's account is possibly reflected a Lechitic origin of the Croats, while in the Croatian origo gentis a migration of seven tribes and chieftains.[269][204]

Curiously, Croats are seemingly the only Slavic people who had a saga about the period of their migration,[270] and the names are the earliest example of pan-Slavic totemic heroes.[271] Also, compared to other early medieval stories none of them mentions female personalities, but do late medieval Kievan, Polish and Czech chronicles,[272] which could indicate a specific tribal and social organization among the Croats.[214] For example, Łowmiański considered the Mazovians, Dulebes, Croats and Veleti among the oldest Slavic tribes because Mazovians ethnonym was often related to Amazons (-maz-) while the land of women in North Europe was mentioned by Paul the Deacon, Alfred the Great, as well women's city West of Russian lands by Abraham ben Jacob.[273] Another vagueness is a reason and meaning that one of the brothers had a Croatian ethnonym as a name, perhaps indicating he was more important than the other brothers, it was the most prominent clan or tribe around which other gathered, or that the Croats were only one identity among others with which the Adriatic Croats tried to bring legitimacy to the Croatian Kingdom.[214][274]

The origin of the names of five brothers and two sisters are a matter of dispute. They are often considered to be of non-Slavic origin,[8][57][275] and genuine names, as the anonymous Slavic narrator (probably a Croat) couldn't invent the non-Slavic names of their ancestors in the 9th century.[276] J.J. Mikkola considered them to be of Turkic-Avar origin,[277][278][279] Vladimir Košćak of possible Iranian-Alanic origin,[280] Karel Oštir as pre-Slavic,[275] while Alemko Gluhak saw parallels in Slavic Old Prussian and Baltic languages.[281] Stanisław Zakrzewski and Henri Grégoire rejected Turkic origin, and related them to Slavic toponyms in Poland and Slovakia,[282][283] while Josip Modestin connected their names to toponyms from region of Lika in Croatia, where early Croats settled.[284] According to Gluhak, names Kloukas, Lobelos, Kosentzes and possibly Mouchlo don't seem to be part of Scythian or Alanic name directory.[285]

Brothers:

- Kloukas; has Greek suffix "-as", thus the root Klouk- has several derivations; Mikkola considered Turkic Külük, while Tadeusz Lewicki Slavic Kuluk and Kluka.[286] Grégoire related it with cities Cracow or Głogów.[283] Modestin related it to village Kukljić.[284] Vjekoslav Klaić and Vladimir Mažuranić related to the Kukar family, one of the Twelve noble tribes of Croatia.[287][288] Mažuranić additionally related to contemporary surnames Kukas, Kljukaš, Kljuk.[289] Gluhak noted several Prussian and Latvian personal names and toponyms with root *klauk-, which relates to sound-writing verbs *klukati (peck) and *klokotati (gurgle).[285] Another consideration is it corresponds to mythical figures, Czech Krok and Polish Krak, meaning the "raven".[271]

- Lobelos; Mikkola considered it a name of uncertain Avar ruler.[286] Grégoire related it with city Lublin.[283] Modestin related it to Lovinac.[284] Rački considered Ljub, Lub, Luben, while Mažuranić noted similar contemporary surnames like Lubel.[290] Osman Karatay considered common Slavic shift Lobel < Alpel (as in Lab < Elbe).[291] Gluhak noted many Baltic personal names with root *lab- and *lob- e.g. Labelle, Labulis, Labal, Lobal, which derive from *lab- (good) or lobas (bays, ravine, valley).[292] Another consideration is it corresponds as male equivalent to female mythical figures, Czech Libuše and Kievan Lybed, meaning the "swan".[271]

- Kosentzis; Mikkola considered Turkic suffix "-či", and derived it from Turkic koš (camp), košun (army).[286] Grégoire related it with city Košice.[283] Modestin related it to Kosinj.[284] Mažuranić considered it similar to contemporary male names Kosan, Kosanac, Kosančić and Kosinec.[293] Many scholars consider relation with Old-Slavic title word *kosez or *kasez, that meant social class members who freely elected the knez of Carantania (658–828). In the 9th century they became nobles, and their tradition preserved until the 16th century. There were many toponyms with the title in Slovenia, but also in Lika in Croatia.[275][23] Gluhak also noted Baltic names with root *kas- which probably derives from kàsti (dig), and Thracian Kossintes, Cosintos, Cositon.[294] Aleksandar Loma considered to be an evidence of Polish-Old Croatian isogloss kъsçzъ in both the personal name and Polish Ksiądz.[295]

- Mouchlo; Mikkola related it to the name of 6th century Hunnic (Bulgar[291] or Kutrigur[296]) ruler Mougel/Mouâgeris.[286] Modestin related it to Mohl(j)ić.[284] Mažuranić considered tribe and toponym Mohlić also known as Moglić or Maglić in former Bužani župa, as well medieval toponym or name Mucla, contemporary surnames Muhoić, Muglič, Muhvić, and Macedonian village Mogila (Turk. Muhla).[297] Emil Petrichevich-Horváth related it to the Mogorović family, one of the Croatian "twelve noble tribes".[298] Gluhak noted Lithuanian muklus and Latvian muka which refer to the mud and marshes, and Prussian names e.g. Mokil, Mokyne.[299]

- Chrobatos; read as Hrovatos, is generally considered to represent Croatian ethnonym Hrvat/Horvat, and the Croatian tribe.[269] Some scholars like J. B. Bury related it with the Turkic name of the Bulgars khan Kubrat.[77][300] This etymology is problematic, beside from historical viewpoint, as in all forms of Kubrat's name, the letter "r" is third consonant.[300]

Sisters:

- Touga; Mikkola related it with male Turkic name Tugai.[286] Modestin and Klaić related it to the Tugomirić family, one of the Croatian "twelve noble tribes",[284] as well Klaić noted that in 852 was a settlement Tugari in the Kingdom of Croatia which people in Latin sources were called as Tugarani and Tugarini,[287] while Mažuranić noted certain Tugina and župan Tugomir.[301] Gluhak noted Old Norse-Germanic *touga (fog, darkness), which meaning wouldn't be much different from other names with Baltic derivation.[302]

- Bouga; Mikkola related it with male Turkic name Buga, while Lewicki noted Turkic name of Hun Bokhas, Peceneg Bogas, and two generals of Arabian kalifs, Bogaj.[278] Grégoire related it with the Bug River.[283] Modestin and Klaić related it to East-Slavic medieval tribe Buzhans who lived on Bug River, as well medieval Croatian tribe Bužani and its župa Bužani or Bužane.[284][287] Gluhak noted Proto-Slavic word *buga which in Slavic languages mean "swamp" like places, and the river Bug itself derives from.[302]

First ruler:

- Porga from 31st chapter according to Živković derives from Iranian pouru-gâo, "rich in cattle".[303] Mažuranić noted it was a genuine personal name in medieval Croatia at least since 12th as well Bosnia since 13th century in the form of Porug (Porugh de genere Boić, nobilis de Tetachich near terrae Mogorovich), Poruga, Porča, Purća / Purča, and Purđa (vir nobilis nomine Purthio quondam Streimiri).[304] However, in the 30th chapter, it is named Porin, and recently Milošević, Alimov, and Budak supported a thesis which considered these names as two variants of the Slavic deity Perun, as a heavenly ruler and not an actual secular ruler.[305][306]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Subtelny 2009, p. 57.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 49.

- ^ a b Dzino 2010, pp. 113, 21.

- ^ a b Paščenko 2006, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Magocsi 2005, p. 5.

- ^ a b Majorov 2012, p. 78.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Rončević, Dunja Brozović (1993). "Na marginama novijih studija o etimologiji imena Hrvat" [On some recent studies about the etymology of the name Hrvat]. Folia Onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (2): 7–23. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Matasović, Ranko (2008), Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika [A Comparative and Historical Grammar of Croatian] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, p. 44, ISBN 978-953-150-840-7

- ^ a b c Charvát, Petr (2010). The Emergence of the Bohemian State. BRILL. pp. 78, 80, 102. ISBN 978-90-474-4459-6.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 115, 168, 444.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 98.

- ^ Pohl, Heinz-Dieter (1970). "Die slawischen Sprachen in Jugoslawien" [The Slavic languages in Yugoslavia]. Der Donauraum (in German). 15 (1–2): 72. doi:10.7767/donauraum.1970.15.12.63 (inactive 31 October 2021).

Srbin, Plural Srbi: "Serbe", wird zum urslawischen *sirbŭ "Genosse" gestellt und ist somit slawischen Ursprungs41. Hrvat "Kroate", ist iranischer Herkunft, über urslawisches *chŭrvatŭ aus altiranischem *(fšu-)haurvatā, "Viehhüter"42.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ^ Arumaa, Peeter (1976). Urslavische Grammatik: Einführung in das vergleichende Studium der slavischen Sprachen (in German). C. Winter. p. 180. ISBN 978-3-533-02283-1.

- ^ Kunstmann, Heinrich (1982). "Über den Namen der Kroaten" [About the name of the Croatians]. Die Welt der Slawen (in German). 27: 131–136.

- ^ Trunte, Hartmut (1990). Slovĕnʹskʺi i︠a︡zykʺ: Ein praktisches Lehrbuch des Kirchenslavischen in 30 Lektionen : zugleich eine Einführung in die slavische Philologie (in German). Sagner. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-87690-716-1.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 86–100, 129.

- ^ Matasović, Ranko (2019), "Ime Hrvata" [The Name of Croats], Jezik (Croatian Philological Society) (in Croatian), Zagreb, 66 (3): 81–97

- ^ Heršak & Nikšić 2007, p. 262.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 36–37, 40–43.

- ^ a b c Marčinko 2000, pp. 318–319, 433.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Danylenko 2004, pp. 1–32.

- ^ Škegro 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 88, 91–92.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 87–95.

- ^ a b c Łowmiański 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 167.

- ^ a b Niederle, Josef (2015). "Alemure, Cumeoberg, Mons Comianus, Omuntesberg, Džrwáb, Wánít. Lokalizace záhadných míst z úsvitu dějin Moravy" [Localization of enigmatic places from the early history of Moravia and Slavs]. Skalničkářův rok. 71A. ISSN 1805-1170. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Živković 2012, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Kim 2013, pp. 146, 262.

- ^ Magocsi 1983, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Синиця, Є.В. "ХОРВАТИ". Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 5 July 2019.

Їх часто необґрунтовано називають також "білими хорватами". Це пов’язано з тим, що східноєвроп. Х. помилково ототожнюють з "хорватами білими" (згадуються в недатованій частині "Повісті временних літ" в одному ряду із сербами й хорутанами) та "білохорватами" (фігурують у трактаті візант. імп. Константина VII Багрянородного "Про управління імперією"); насправді в обох випадках ідеться про слов’ян. племена на Балканах – предків населення сучасної Хорватії.

- ^ Voitovych, Leontii (2011). "Проблема "білих хорватів"". Галицько-волинські етюди (PDF). Біла Церква. ISBN 978-966-2083-97-2. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

Trans.: Proceeding from the above, Transcarpathian Croats and Croats lived near Dniester and San Rivers would be more correct to call Carpathian Croats, as Ya. Isayevich suggested, and not White Croats, as most Ukrainian and Russian authors write. White Croats were located in the upper reaches of the Vistula and Oder, in Saala and White Elster, where S. Panteleich sought out entire areas that still enjoyed autonomy in the 14th-15th centuries, and the remnants of toponymy.

- ^ А. В. Майоров (2017). "ХОРВА́ТЫ ВОСТОЧНОСЛАВЯ́НСКИЕ". Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Bolshaya Rossiyskaya Entsiklopediya, Russian Academy of Sciences.

По данным ср.-век. письм. источников и топонимии, хорваты локализуются на северо-западе Балкан (предки совр. хорватов); на части земель в бассейнах верхнего течения Эльбы, Вислы, Одры, возможно, и Моравы (белые хорваты, по-видимому, в значении "западные"); на северо-востоке Прикарпатья (отчасти и в Закарпатье).

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 102.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 42–54.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 115, 168.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 110.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 444, 451, 501, 516.

- ^ Košćak 1995, p. 111.

- ^ a b Paščenko 2006, p. 141.

- ^ a b Sedov 2013, pp. 168, 444, 451.

- ^ Heršak & Nikšić 2007, p. 263.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 42–43.

- ^ a b Majorov 2012, p. 155–157, 180.

- ^ Magocsi 1983, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f Magocsi 2002, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Van Antwerp Fine Jr. 1991, pp. 53, 56.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 58.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b c Korčinskij 2006a, p. 37.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Škegro 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Norris 1993, p. 15.

- ^ Langston, K.; Peti-Stantic, A. (2014). Language Planning and National Identity in Croatia. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 57–60. ISBN 978-1-137-39060-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz (1951). "Zagadnienie Chorwatów nadwiślańskich" [The problem of Vistula Croats]. Pamiętnik Słowiański (in Polish). 2: 17–32.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 8–9, 11, 13–14, 22.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 53.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Živković 2012, pp. 111–122.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 71–72.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 70–73.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Živković 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Chrzanowski, Witold (2008). Kronika Słowian: Polanie. Libron. pp. 177, 192. ISBN 978-83-7396-749-6.

- ^ a b c Heršak & Nikšić 2007, p. 259.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 130.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 99–100.

- ^ Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1962). Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Adminstrando Imperio: Volume 2, Commentary. Athlone Press. pp. 139, 216.

- ^ Paszkiewicz, Henryk (1977). The Making of the Russian Nation. Greenwood Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-8371-8757-0.

- ^ Živković, Tibor (2001). "О северним границама Србије у раном средњем веку" [On the northern borders of Serbia in the early middle ages]. Zbornik Matice srpske za istoriju (in Serbian). 63/64: 11.

Plemena u Zahumlju, Paganiji, Travuniji i Konavlima Porfirogenit naziva Srbima,28 razdvajajuči pritom njihovo političko od etničkog bića.29 Ovakvo tumačenje verovatno nije najsrećnije jer za Mihaila Viševića, kneza Zahumljana, kaže da je poreklom sa Visle od roda Licika,30 a ta je reka isuviše daleko od oblasti Belih Srba i gde bi pre trebalo očekivati Bele Hrvate. To je prva indicija koja ukazuje da je srpsko pleme možda bilo na čelu većeg saveza slovenskih plemena koja su sa njim i pod vrhovnim vodstvom srpskog arhonta došla na Balkansko poluostrvo.

- ^ Živković 2012, pp. 49, 54, 83, 88.

- ^ Živković 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 56, 78–80.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Ingram 1807, p. 72.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 210.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 48–53.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 51, 57–60, 94, 125–126.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 51–52, 56, 59.

- ^ Koncha 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Kugutjak 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Tomenčuk 2017, p. 32.

- ^ a b Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c.900–c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-107-65139-5.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Łowmiański 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 16, 18, 59, 94, 125–126.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b Vernadsky 2008, pp. 262–263.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 212.

- ^ a b c Majorov 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 211.

- ^ a b Zimonyi 2015, pp. 295, 319.

- ^ Wexler, Paul (2019). "How Yiddish can recover covert Asianisms in Slavic, and Asianisms and Slavisms in German (prolegomena to a typology of Asian linguistic influences in Europe)". In Andrii Danylenko, Motoki Nomachi (ed.). Slavic on the Language Map of Europe: Historical and Areal-Typological Dimensions. De Gruyter. p. 239. ISBN 978-3-11-063922-3.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 62, 64, 66.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 62, 66.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006a, p. 32.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 61–63.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 61–63, 65.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 64–68.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 214.

- ^ a b Łowmiański 2004, p. 84–86.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 53, 66–67.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 56.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 64.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 54, 69.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 119.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 144.

- ^ Hanak 2013, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Paščenko 2006, p. 123.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 250.

- ^ Magocsi 1983, p. 56.

- ^ Korčinskij 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006a, p. 39.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 147.

- ^ Klaić, Vjekoslav (1978). Hrvati i Hrvatska: Ime Hrvat u historiji slavenskih naroda. Liber Verlag. p. 62.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 68–69, 112–113.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 150.

- ^ Vach 2006, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b Kalhous, David (2012). Anatomy of a Duchy: The Political and Ecclesiastical Structures of Early P?emyslid Bohemia. BRILL. p. 75. ISBN 978-90-04-22980-8.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Kantor, Marvin (1983). Medieval Slavic Lives of Saints and Princes. University of Michigan, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. pp. 150, 157, 160. ISBN 978-0-930042-44-8.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 68–71.

- ^ MacArtney, C. A. (2008). The Magyars in the Ninth Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126, 136–138, 149. ISBN 978-0-521-08070-5.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 70–71.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 148.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 19, 87–89, 94–95.

- ^ Sedov 2013, p. 428.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 149.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Vach 2006, p. 239.

- ^ Widajewicz 2006, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Vach 2006, pp. 240–242.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 19, 94.

- ^ Sedov 2013, p. 431.

- ^ a b c Gluhak 1990, p. 151.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 158.

- ^ Marčinko 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Fokt 2004.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 161–167.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 161.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 162.

- ^ Jirásek 2015.

- ^ a b Alimov 2015, p. 153.

- ^ Sedov 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Jaroslav Rudnyckyj (1982). An Etymological Dictionary of the Ukrainian Language: Parts 12–22 (in English and Ukrainian). Vol. 2. Winnipeg: Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences (UVAN). p. 968.

- ^ Malyckij 2006, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b Paščenko 2006, pp. 99–102, 109.

- ^ Malyckij 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Strižak 2006, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Strižak 2006, p. 187.

- ^ Pendergrass 2015, p. 75.

- ^ Shippey 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 30–31.

- ^ Lewicki 2006, p. 95.

- ^ Acker & Larrington 2013, p. 245.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 96.

- ^ Lewicki 2006, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Vašica 2008, pp. 242, 244, 247–248, 250–258.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 145.

- ^ United States Immigration Commission 1911, pp. 22, 40, 43, 88, 105.

- ^ Novaković, Relja (1977). Odakle su Srbi dos̆li na Balkansko poluostrvo (in Serbo-Croatian). Beograd: Istorijski institut. p. 335.

- ^ Nikčević, Vojislav (2002). Kroatističke studije (in Serbo-Croatian). Erasmus Naklada. p. 221. ISBN 9789536132584.

- ^ Struk 1993, p. 189, Ph - Sr. Vol. 4.

- ^ "White Croatians". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. 2005.

They are believed to be the ancestors of certain Ukrainians, specifically the Hutsuls...

- ^ Magocsi 1995.

- ^ Motta, Giuseppe (2014). Less than Nations: Central-Eastern European Minorities after WWI, Volumes 1 and 2. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4438-5859-5.

There were different theories to explain the presence of Rusyns. In his The settlements, economy and history of the Rusyns of Subcarpathia (1923) A. Hodinka wondered if Russians arrived before the Magyars, at the same time or later? Were they White Croats? Slavs who mixed with nomad Vlachs?

- ^ И.А. Бойко (2016). "ДОЛЫНЯ́НЕ". Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Bolshaya Rossiyskaya Entsiklopediya, Russian Academy of Sciences.

Сформировались на основе вост.-слав. населения 7–9 вв. (хорваты, или белые хорваты), вошедшего в 10 в.

- ^ a b Rabii-Karpynska, Sofiia (2013). "Boikos". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

The Boikos are believed to be the descendants of the ancient Slavic tribe of White Croatians that came under the rule of the Kyivan Rus' state during the reign of Prince Volodymyr the Great. Before the Magyars occupied the Danube Lowland this tribe served as a direct link between the Eastern and Southern Slavs.

Article from Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Vol. 1. University of Toronto Press. 1984. ISBN 978-0802033628. - ^ В.А. Войналович (2003). "БОЙКИ". Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Naukova Dumka, NASU Institute of History of Ukraine. p. 688. ISBN 966-00-0734-5.

Гадають, що Б. – нащадки давнього слов'ян. племені білих хорватів, яких Володимир Святославич приєднав до Київської Русі

- ^ Nicolae Pavliuc; Volodymyr Sichynsky; Stanisław Vincenz (2001) [1989]. "Hutsuls". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Vol. 2. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0802033628.

The Slavic White Croatians inhabited the region in the first millennium AD; with the rise of Kyivan Rus', they became vassals of the new state.

- ^ Л.В. Ковпак (2004). "ГУЦУЛИ". Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (in Ukrainian). Vol. 2. Naukova Dumka, NASU Institute of History of Ukraine. ISBN 966-00-0632-2.

Г. – нащадки давніх слов'ян. племен – білих хорватів, тиверців й уличів, які в 10 ст. входили до складу Київської Русі ... Питання походження назви "гуцули" остаточно не з'ясоване. Найпоширеніша гіпотеза – від волоського слова "гоц" (розбійник), на думку ін., від слова "кочул" (пастух).

- ^ a b "Wooden Tserkvas of the Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine" (PDF) (Press release). Warsaw – Kiev. UNESCO. 2011. pp. 153, 9. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

The city of Rohatyn is situated at the crossroads of routes leading to Halych, Lviv and Ternopil. Evidence of two large White Croatian towns (6th-8th centuries) was found near Rohatyn at the villages of Pidhoroddya and Lykovyshche. One of them is likely to have been Old Rohatyn ... The Lemkos an ethnic group inhabiting the Eastern Carpathians, between the River of Poprad to the west and the rivers of Oslava and Laborec to the east. The ethnic shape of the Lemko territory was affected by the Wallachian colonization in 14th-16th centuries, the influx of a Ruthenian-influenced Slovak population and the settlement of a Slavic tribe called the White Croats, who had inhabited this part of the Carpathians since the 5th century.

- ^ Magocsi 2015, p. 29.

- ^ Katchanovski, Ivan; Kohut, Zenon E.; Nebesio, Bohdan Y.; Yurkevich, Myroslav (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Scarecrow Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-8108-7847-1.

In the opinion of some scholars, the ancestors of the Lemkos were the White Croatians, who settled the Carpathian region between the seventh and tenth centuries.

- ^ Van Antwerp Fine Jr. 1991, pp. 26–41.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 93.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 168, 444, 451, 501, 516.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 12, 23.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 93–94.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 60–64.

- ^ a b c Kardaras 2018, p. 93.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 169, 175–177, 444, 450.

- ^ Heršak & Silić 2002, pp. 211–213.

- ^ a b Sedov 2013, p. 450.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 217.

- ^ a b c Majorov 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 182, 450.

- ^ Kardaras 2018, p. 94.

- ^ a b Łowmiański 2004, p. 23–24.

- ^ a b c Budak 2018, p. 97.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 176, 446, 460.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Bilogrivić 2010, pp. 37, 48.

- ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 159–169, 175–177, 444, 450–452.

- ^ Bilogrivić 2010, pp. 39, 44.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 103.

- ^ Bilogrivić 2010, pp. 37–38, 48.

- ^ Budak 2018, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Sedov 2013, p. 446.

- ^ Bilogrivić 2010, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Sedov 1979, p. 131–132.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 130–134.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 85, 131, 168.

- ^ Majorov 2012, pp. 85–86, 168.

- ^ Козак, В. Д. (1999). Етногенез та етнічна історія населення Українських Карпат (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Lviv: Institute of Ethnology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. pp. 483–502.

- ^ Cvijanović, Irena (2013). "The Typology of Early Medieval Settlements in Bohemia, Poland and Russia". In Rudić, Srđan (ed.). The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Istorijski institut. pp. 289–344. ISBN 978-86-7743-104-4.

- ^ Синиця Є.В. (2013). "ХОРВАТИ". Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (in Ukrainian). Vol. 10. Naukova Dumka, NASU Institute of History of Ukraine. ISBN 978-966-00-1359-9.

...єдине з літописних племен, для котрого "Повість временних літ" не вказує територію розселення. Локалізація Х. у Прикарпатті та, можливо, Закарпатті базується на двох підставах: 1) у цих регіонах у 8—10 ст. поширені пам’ятки райковецької культури, притаманної всім східнослов’ян. племенам Правобережжя в зазначений час; 2) ця частина ареалу райковецької к-ри лежить поза межами розселення ін. літописних племен, згаданих у "Повісті временних літ". Гомогенність райковецьких старожитностей, які не членуються на відносно чіткі локальні варіанти, не дає змоги конкретизувати кордони Х. та їхніх сусідів (волинян/бужан на пн. та пн. сх., уличів на пд. сх. і тиверців на пд.). Певною особливістю райковецьких пам’яток Прикарпаття є поширеність городищ-сховищ, що були одночасно сакральними центрами (мали капища та "довгі будинки"-контини, призначені для общинних бенкетів-братчин).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ Абашина Н.С. "РАЙКОВЕЦЬКА КУЛЬТУРА". Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (in Ukrainian). Naukova Dumka, NASU Institute of History of Ukraine. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

Носіями Р.к. були літописні племена – поляни, уличі, древляни, волиняни, бужани, хорвати, тиверці.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006a, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Korčinskij 2000, pp. 113–120.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006a, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d e f uk:Гупало Віра Діонізівна, Звенигород і Звенигородська земля у ХІ–ХІІІ століттях (соціо-історична реконструкція) (in Ukrainian), Львів: Інститут українознавства ім. І. Крип'якевича НАН України, 2014, pages 73-80, 81-96

- ^ Korčinskij 2000, p. 120.

- ^ a b c uk:Филипчук Михайло Андрійович, "ПЛІСНЕСЬКИЙ АРХЕОЛОГІЧНИЙ КОМПЛЕКС: ТЕОРІЯ І ПРАКТИКА ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ" (in Ukrainian), Proc. Inst. Archaeol. Lviv. Univ., volume 10, 2015, pages 38–64

- ^ Пліснеський археологічний комплекс (in Ukrainian), published by Municipal institution of the Lviv Regional Council "Administration of historical and cultural reserve "Ancient Plisnesk", 2017

- ^ Korčinskij 2004, p. 2.

- ^ a b Korčinskij 2013a, p. 212.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006b, pp. 68–71.

- ^ Korčinskij 2004, pp. 2–7.

- ^ Korčinskij 2013a, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006b, p. 71.

- ^ Korčinskij 2013a, pp. 210–212.

- ^ Korčinskij 2013a, p. 221.

- ^ Korčinskij 2006b, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Орест-Дмитро Вільчинський, "Нам немає чого стидатися – ми не кращі і не гірші від інших європейських народів" (interview with archaeologist Филипчук Михайло Андрійович: in Ukrainian), Католицький Оглядач, 2 August 2015, quote: Під час походу Володимира на хорватів (992-993 рр.) городище було спалене. Повертаючись до того часу, про який ми зараз говоримо, потрібно сказати, що похід Володимира Великого був нищівним для Галичини, тобто для тодішньої Великої Хорватії (нехрещеної). Населення не хотіло підкоритися Київському князю, оскільки тут було уже своє протодержавне об’єднання – Велика Хорватія, яке перебувало у процесі становлення держави, як колись було у постгомерівській Греції, коли міста-поліси формували Афінський і Пелопоннеський союзи. В той час у нас усе групувалося довкола Галича і це зафіксовано в східних, візантійських та західних писемних джерелах. «Прихід» Володимира в Галичину цілковито руйнує наявну тут територіально-адміністративну інфраструктуру, основою якої були міста-держави, тобто поліси. Отже, слід думати, що ми маємо справу з величезним переселенням частини наших пращурів у Володимир-Суздальську землю. А ще частина населення, не підкорившись загарбникам, пішла на Балкани, у Хорватію, яка там виникла за часів візантійського царя Іраклія в 617 році. Тобто, в ХІ столітті в Галичині склалася дуже важка ситуація, тому вона не випадково практично зникає зі сторінок писемних джерел. Не дивно, що сказане знаходить своє підтвердження і в археологічних джерелах. Так, якщо в кінці Х століття в українському Прикарпатті функціонувало щонайменше 86 міст (разом з культовими центрами) і понад 500 селищ (усе це до тепер знайдено, але очевидно їх було більше), то в ХІ столітті в ми ледве нараховуємо до 40 населених пунктів. Похід Володимира на хорватів – це був страшний катаклізм. Подібна ситуація була і в тих землях, які захопили Болєслав І і його син Мєшко ІІ на території сучасної Польщі. На цих теренах Велика Хорватія сягала західніше від Кракова. І тому не випадково, коли в середині ХІІ століття відроджується Галич, давньоруське місто повторює матрицю старохорватських міст-держав. Тому, коли Володимир йшов війною на хорватів, він мав, якесь певне моральне оправдання – хрещення закоренілих поган. Але не відкидаймо його політичні та економічні інтереси. Адже, з одного боку цей «поганський клин» знаходився на практично ключовій позиції Бурштинового шляху, контролюючи перехід з басейну Балт��йського моря у басейн Чорного, а також і тогочасна політична експансія руської та польської держав, очевидно вимагала оптимального політичного вирішення цього питання.

- ^ Korčinskij 2013b, p. 264.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Sedov 2013, p. 502.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 118.

- ^ Моця О.П. (2008). "КУРГАНИ СХІДНОСЛОВ'ЯНСЬКІ". Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (in Ukrainian). Vol. 5. Naukova Dumka, NASU Institute of History of Ukraine. ISBN 978-966-00-0855-4.

З'являються на рубежі 2-ї пол. 1 тис., замінюючи безкурганні поховання (крім територій уличів, тіверців і хорватів).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ Sedov 2013, pp. 430, 435–437.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 143.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 144, 146.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 145, 147.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 145.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Paščenko 2006, pp. 67–82, 109–111.

- ^ Budak 2018, pp. 144–148.

- ^ a b Budak 2018, p. 95.

- ^ Budak 2018, p. 89.

- ^ Kardaras 2018, p. 95.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 222.

- ^ Alimov 2015, p. 142.

- ^ a b c Judith Kalik; Alexander Uchitel (11 July 2018). Slavic Gods and Heroes. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-02868-4.

the names of the pan-Slavic totemic ancestral figures: Kloukas corresponds to the Czech Krok and to the Polish Krak—the raven—and Lobelos is a male counterpart of the Czech Libuše and the Kievan Lybed'—the swan. The distorted form of these names probably appeared in Constantine's treatise because of the thirdhand or even fourth-hand nature of the information, which was ultimately derived from the Croatian historical tradition, but reached Constantine through several intermediary sources. Nevertheless, the Croatian material is the earliest evidence available for the names of pan-Slavic totemic heroes.

- ^ Lajoye, Patrice (2019). "Sovereigns and sovereignty among pagan Slavs". In Patrice Lajoye (ed.). New Researches on the Religion and Mythology of the Pagan Slavs. Lingva. pp. 165–181. ISBN 979-10-94441-46-6.

- ^ Sedov 2013, p. 481.

- ^ Goldstein, Ivo (1989). "O etnogenezi Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku" [On the ethnogenesis of the Croats in the Early Middle Ages]. Migracijske i etničke teme (in Croatian). 5 (2–3): 221–227. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Gušić, Branimir (1969). "Prilog etnogenezi nekih starohrvatskih rodova" [A contribution to the ethnogenesis of some Old Croatian genera]. Radovi (in Croatian). Zadar: JAZU. 16–17: 449–478.

- ^ Živković 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 34–35.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Margetić 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 126, 218.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 218–221.

- ^ Łowmiański 2004, p. 17, 35.

- ^ a b c d e Karatay 2003, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gluhak 2000, p. 21.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 218.

- ^ a b c d e Gluhak 1990, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Klaić, Vjekoslav (1897), "Hrvatska plemena od XII. do XVI. stoljeća" [Croatian tribes from 12th until 16th century], Rad (in Serbo-Croatian), Zagreb: JAZU (47): 15, 85

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, p. 408.

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, pp. 408, 555.

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, pp. 408, 607.

- ^ a b Karatay 2003, p. 92.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 219.

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, pp. 408, 528.

- ^ Gluhak 1990, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Majorov 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 99.

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, pp. 408, 528, 677, 688.

- ^ Petrichevich-Horváth, Emil (1933), "A Mogorovich Nemzetseg: Adatok a horvát nemzetségek történetéhez." [The Mogorovich Genus: Data on the history of Croatian genera], Turul (in Hungarian), Budapest: Hungarian Heraldic and Genealogical Society (1/2)

- ^ Gluhak 1990, p. 220.

- ^ a b Karatay 2003, pp. 86–91.

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, pp. 408, 1473.

- ^ a b Gluhak 1990, p. 221.

- ^ Živković 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Mažuranić 1908–1922, pp. 89, 253, 942, 1007, 1010, 1029, 1197, 1619.

- ^ Alimov 2015, pp. 141–164.

- ^ Budak 2018, pp. 95–96.

Sources[]

- Acker, Paul; Larrington, Carolyne (2013). Revisiting the Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Heroic Legend. Routledge. ISBN 9781136227875.

- Alimov, Denis Jevgenjevič (2015). "Hrvati, kult Peruna i slavenski gentilizam (Komentari na hipotezu Ante Miloševića o identitetu Porina i Peruna)" [Croats, the cult of Perun and Slavic "gentilism". (A Comment on the hypothesis of Ante Miloševic about the identity of Porin and Perun)]. Starohrvatska Prosvjeta. III (42): 141–164.

- Bilogrivić, Goran (2010). "Čiji kontinuitet? Konstantin Porfirogenet i hrvatska arheologija o razdoblju 7–9. stoljeća" [Whose continuity? Constantine Porphyrogenitus and Croatian archaeology on the period of the 7th to the 9th centuries]. Radovi (in Croatian). Zagreb: Institute of Croatian History, Faculty of Philosophy Zagreb, FF press. 42 (1): 37–48 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Budak, Neven (2018). Hrvatska povijest od 550. do 1100 [Croatian history from 550 until 1100]. Leykam international. ISBN 978-953-340-061-7.

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P., eds. (1953). The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Medieval Academy of America.

- Danylenko, Andrii (2004). "The name Rus': In search of a new dimension". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas (52): 1–32.

And the tribe which lives near them [the Amazons] is the Harus [Hrus/Hros], tall, big-limbed men, who have no weapons of war, and horses cannot carry them because of the bigness of their limbs.

- Dzino, Danijel (2010). Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia. BRILL. ISBN 9789004186460.

- Van Antwerp Fine Jr., John (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472081493.

- Fokt, Krzysztof (2003), "Chorwacja północna: między rzeczywistością, hipotezą a legendą" [Northern Croatia: between reality, conjecture, and legend], Acta Archaeologica Carpathica (in Polish), 38: 137–155, ISSN 0001-5229

- Fokt, Krzysztof (2004). "Biali Chorwaci w Karantanii". Studenckie Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Studenckie Zeszyty Historyczne (in Polish): 11–22.

- Gluhak, Alemko (1990), Porijeklo imena Hrvat [Origin of the name Croat] (in Croatian), Zagreb, Čakovec: Alemko Gluhak

- Gluhak, Alemko (24 March 2000). "Hrvatski rječnici" [Croatian dictionaries]. Vijenac (in Croatian). No. 158. Matica hrvatska.

- Golden, Peter Benjamin (1992). An introduction to the History of the Turkic peoples: ethnogenesis and state formation in medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447032742.

- Hanak, Walter K. (2013). The Nature and the Image of Princely Power in Kievan Rus', 980-1054: A Study of Sources. BRILL. ISBN 9789004260221.

- Heršak, Emil; Nikšić, Boris (2007), "Hrvatska etnogeneza: pregled komponentnih etapa i interpretacija (s naglaskom na euroazijske/nomadske sadržaje)" [Croatian Ethnogenesis: A Review of Component Stages and Interpretations (with Emphasis on Eurasian/Nomadic Elements)], Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian), 23 (3)

- Heršak, Emil; Silić, Ana (2002), "Avari: osvrt na njihovu etnogenezu i povijest" [The Avars: A Review of Their Ethnogenesis and History], Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian), 18 (2–3)

- Ingram, James (1807). An Inaugural Lecture on the Utility of Anglo-Saxon Literatures to which is Added the Geography of Europe by King Alfred, Including His Account of the Discovery of the North Cape in the Ninth Century. University Press.

- Jirásek, Alois (2015). "4". Staré pověsti české. ISBN 9788088061144. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- Kardaras, Georgios (2018). Florin Curta; Dušan Zupka (eds.). Byzantium and the Avars, 6th-9th Century AD: political, diplomatic and cultural relations. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-38226-8.

- Karatay, Osman (2003). In Search of the Lost Tribe: The Origins and Making of the Croatian Nation. Ayse Demiral. ISBN 9789756467077.

- Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107009066.

- Koncha, S. (2012). "Bavarian Geographer on Slavic Tribes From Ukraine" (PDF). Ukrainian Studies. Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. 12: 15–21.

- Korčinskij, Orest (2000), "Gradišta ljetopisnih (istočnih) Hrvata 9.-14. stoljeća u području Gornjeg Podnestrovlja", Contributions of Institute of Archaeology in Zagreb, Institute of archaeology in Zagreb, 17 (1): 113–127

- Korčinskij, Orest (2004), "Cult Centres of Croats from the 9th to the 14th Century in the Environs of the Ruin of Stiljsko, Ukraine", Croatica Christiana Periodica, The Catholic faculty of theology, 28 (54)

- Korčinskij, Orest (2006a). "Bijeli Hrvati i problem formiranja države u Prikarpatju" [Eastern Croats and the problem of forming the state in Prykarpattia]. In Nosić, Milan (ed.). Bijeli Hrvati I [White Croats I] (in Croatian). Maveda. pp. 31–39. ISBN 953-7029-04-2.

- Korčinskij, Orest (2006b). "Stiljski grad" [City of Stiljsko]. In Nosić, Milan (ed.). Bijeli Hrvati I [White Croats I] (in Croatian). Maveda. pp. 68–71. ISBN 953-7029-04-2.

- Korčinskij, Orest (2013a). "O povijesnoj okolici stiljskoga gradišta od kraja 8. stoljeća do početka 11. st." [City of Stiljsko]. In Nosić, Milan (ed.). Bijeli Hrvati III [White Croats III] (in Croatian). Maveda. pp. 210–224. ISBN 978-953-7029-27-2.

- Korčinskij, Orest (2013b). "Stiljsko gradište" [Gord of Stilsko]. In Nosić, Milan (ed.). Bijeli Hrvati III [White Croats III] (in Croatian). Maveda. pp. 246–264. ISBN 978-953-7029-27-2.

- Košćak, Vladimir (1995), "Iranska teorija o podrijetlu Hrvata" [Iranian theory on the origin of Croats], in Budak, Neven (ed.), Etnogeneza Hrvata [Ethnogenesis of Croats] (in Croatian), Matica Hrvatska, ISBN 953-6014-45-9

- Kugutjak, Mykola (2017). "Spomenici povijesti i kulture: Gradišta Pruto-Bystryc'koga podgorja". In Paščenko, Jevgenij; Fuderer, Tetyana (eds.). Prikarpatska Galicija (PDF) (in Croatian). Department of Ukrainian Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb. pp. 20–31. ISBN 978-953-55390-4-9.