William Blair-Bell

William Blair-Bell | |

|---|---|

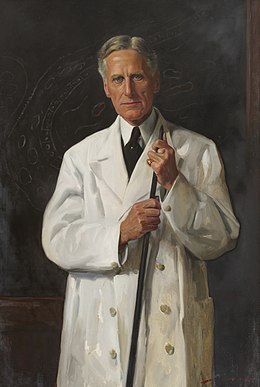

William Blair-Bell in 1931. Note the missing finger, the second finger of the left hand that he lost when he was pricked by a needle while operating and this led to infection and ultimately gangrene, necessitating removal. | |

| Born | William Blair Bell 28 September 1871 New Brighton, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 25 January 1936 (aged 64) in a train near Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | King's College School |

| Known for | Co-founding the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| Spouse(s) | Florence Bell |

| Awards | FRCS |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Obstetrics Gynaecology |

| Institutions | University of Liverpool, Liverpool Royal Infirmary |

William Blair-Bell FRCS (28 September 1871 in Rutland House, New Brighton[1] – 25 January 1936 in Shrewsbury) was a British medical doctor and gynaecologist who was most notable as the founder of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 1929.[2] Blair-Bell was considered the greatest gynaecologist of the 20th century, raising it from what was then a branch of general surgery into a separate medical specialism.[2] He was subject of a biography by Sir John H. Peel.[2][3]

Life[]

Blair-Bell was the son of William Bell, a General practitioner, in a family of nine children and Helen Hilaire Barbara née Butcher, daughter of Major General of the Royal Marines Light Infantry. Blair-Bell's brother John Herbert Bell, was an adjutant at Donington Hall, which was a Prisoner of war camp for enemy soldiers captured during World War I. Another brother of Blair-Bell's was known to be a Cotton factor in St Louis, USA.[1]

Blair-Bell started his early education in 1885, attending Rossall School, leaving in summer 1890.[1] Blair-Bell started his medical career after winning a in 1900[1] to King's College School and attended King's College Hospital.[4] At Kings, Blair-Bell won the for proficiency in diseases in obstetrics and gynaecology.[4] Blair-Bell qualified with the Conjoint Diploma(MB) in 1896, later qualifying with the Doctor of Medicine in 1902.[4] In 1928 Blair-Bell was elected a Fellow to the college.[4]

Career[]

Blair-Bell started his medical career in general practice, but later decided to specialise in obstetrics and gynaecology.[1] In 1905 Blair-Bell was appointed to a position as assistant consulting gynocologist at the Liverpool Royal Infirmary, working as a surgeon, in the outpatient department[4] and as a gynaecologist to the .[1] In 1913, he was appointed to senior gynaecological surgeon to the Royal Infirmary.[1]

In 1921, Blair-Bell became Professor of obstetrics and gynaecology, replacing at the University of Liverpool, a position he held until 1931, when he resigned, becoming the emeritus professor.[1]

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists[]

In 1911, Blair-Bell founded the Gynaecological Visiting Society of Great Britain (GVS).[4] It was a small society with membership limited to 20, and 55 being the age of retirement from the active list. The GVS was organised as a club, with members being elected by strict ballot, based on professional ability and character, with two meetings a year. Its primary purpose was to promote research, with its members meeting in an atmosphere of informality.[4] When it was established, most of its members were relatively young, but by the early 1920s, these same members filled all the chairs of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in all but two universities within the UK and was, therefore, considered a very influential society.[5]

According to Blair-Bell, the idea of a college of obstetricians and gynaecologists was suggested to William Fletcher Shaw, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynaecology in the University of Manchester, by Sir , founder of the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire. Shaw was keen on the idea and formed a plan to create the college.[5] Shaw, who was a member of the GVS, realised the potential of the society as a step to creating the college. In October 1924, Shaw met with Blair-Bell at a rough shooting meet in the North Lancashire fells[6] to discuss the idea and persuade him of its merits. Blair-Bell discussed the idea with several people including Sir Ewen Maclean, the first Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Wales and Sir Comyns Berkeley, obstetric and gynaecological surgeon.[5] Together a plan was formed to discuss the new college idea at the next GVS meeting on 2 February 1925. The GVS were enthused by the idea, and a committee was formed by Shaw, Blair-Bell, Maclean and several others to draw up a detailed plan.[5]

Blair-Bell and the committee members faced considerable difficulties in establishing the college.[5] Blair-Bell and the committee decided to approach some leading Southern England and London based paediatricians, as the GVS was essentially a Liverpool-based club, deciding it would be politically prudent before starting to work on the Memorandum and Articles of Association.[5] In July 1926, Sir Francis Champneys, Sir George Blacker, Thomas Watts Eden, Herbert R. Spencer and Archibald Donald were all approached to meet the committee at Comyns Berkeley's house in London.[5] The group put up considerable resistance to the idea with Herbert R. Spencer providing the most reserved, arguing that there was no need for a new college, arguing that the colleges should be amalgamated into a Royal Academy of Medicine. George Blacker also criticised the plan, stating that it was against the vested interest of the established colleges. The greatest problem identified was whether the new institution should be an association or college. Blair-Bell was uncompromising in his action that it should be a college.[5]

The Royal Colleges also provided the most resistance to the establishment of the new college, e.g. Royal College of Surgeons of England, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and the Royal College of Physicians.[2] They opposed not only the formation of the new college but when they lost that battle, also resisted the new college's right to offer its own examinations and qualifications in obstetrics and gynaecology.[2] The resistance from the Royal Colleges made Blair-Bell and Shaw realise that the college would never get permission to be founded, if there was resistance to the idea, and several months of negotiations with the colleges by Blair-Bell and Shaw failed to find agreement.

To circumvent the resistance, the committee decided to establish the college as a Limited company with possible special dispensation to remove the Ltd part from the name but proved problematic. Finally, the Board of Trade decided to hold an enquiry to find consensus between the Royal Colleges and the committee, but this proved impossible and in May 1929, the board decided to refuse registration. However, following the Second Baldwin ministry, the committee had a contact in the Conservative government, Sir Boyd Merriman who was able to arrange a meeting with Neville Chamberlain who agreed, and put pressure on the Royal Colleges to agree.[5] Taking almost four years to form the college, it was founded in 26 August 1929, with Blair-Bell as its President from its forming until 1932, Fletcher Shaw as Honorary Secretary and Comyns Berkeley as the treasurer[7][5] However, it was not until 1943, that the Royal College of Surgeons invited the new College to take part in the Conjoint board examinations.

Blair-Bell and Shaw wrote the original charter and drew up the by-laws while Blair-Bell devised the ceremonial gowns and the beginnings of the membership examinations.[6] Blair-Bell would later anonymously donate the money for the first college building at 58 Queen Anne Street, London.[6]

Awards and honours[]

Blair-Bell was made Commander of the Order of the Star of Romania and was an honorary member of obstetric and gynaecological societies in Belgium and the United States.[8]

The Blair-Bell medal is named in his honour.[9]

Later life[]

Blair-Bell married a cousin Florence Bell in 1898, she died in 1929 and they had no children.[10] On 25 January 1936 Blair-Bell collapsed on a train on his way home from London to Eardiston House, Shropshire. He was taken to Royal Salop Infirmary in Shrewsbury where he was found to be dead. He was aged 64.[10]

Contributions[]

Blair-Bell displayed a particular knack for research and writing scientific papers while still a medical student.[4] Those who knew him considered him difficult, ruthless, overbearing and complex,[1] but also lucid and interesting while at university,[1] with his achievements outweighing any failings.[4] Lord Dawson, described him as a loveable character who never forgot, or allowed anyone else to forget, that he was bearing the torch. He was banned from the University of Liverpool department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology until he was appointed to the Chair in 1931, and after turning up a day early, Professor Henry Briggs commented, Bell, you are an abortion, you are here before your time.[4]

Blair-Bell's early research concentrated on gynaecological endocrinology. Blair-Bell was also interested in the causes and treatment of cancer.[4] From 1909, he started to research and experiment with placental and embryonic extractions.[1] When this proved fruitless, Blair-Bell started to experiment with the use of Lead as a treatment, assuming that as an abortifacient, it could reduce or inhibit the growth of cancer. From 1921, he was using lead in the treatment of Uterine cancer,[4] and colloid lead iodide for the treatment of Breast cancer, but later large scale tests proved both painful and dangerous.[1]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l "Blair-Bell, William (1871–1936)". Plarr's Lives of the Fellows Online. The Royal College of Surgeons of England. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Loudon, I (1987). "William Blair-Bell—father and founder". Med Hist. 31 (3): 363–364. doi:10.1017/s0025727300046962. PMC 1139751.

- ^ "The Late William Blair-Bell, M.D., F.R.C.S." Canadian Medical Association Journal. 34 (6): 683–684. 1936. PMC 1561749. PMID 20320291.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l "William Blair-Bell M.D., F.R.C.S." Br Med J. 1 (3918): 287–289. 1936. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3918.287. PMC 2122336.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Ornella Moscucci (22 July 1993). The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England, 1800–1929. Cambridge University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-521-44795-9. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Geoffrey Chamberlain (June 2007). From Witchcraft to Wisdom: A History of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the British Isles. RCOG. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-904752-14-1. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ "O&G pre-20th century and foundation of the College". Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Who Was Who, Volume III, 1929–1940. A and C Black. 1947. pp. 121–122.

- ^ "The Blair-Bell Medal". Br Med J. 2 (4692): 1326–1327. 1950. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4692.1326-b. PMC 2039525.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Prof. Blair-Bell – Gynaecology and Cancer Research". The Times (47282). London. 27 January 1936. p. 17.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Blair-Bell. |

External links[]

- "Diet in Pregnancy Blair-Bell Memorial Lecture". Br Med J. 2 (4219): 703–70. 1941. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4219.703-a. PMC 2163320.

- 20th-century English medical doctors

- 1936 deaths

- 1871 births

- People educated at Rossall School

- Academics of the University of Liverpool

- British gynaecologists