William Joseph Taylor

William Joseph Taylor | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1802 |

| Died | March 1885 Birmingham |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | W. J. Taylor |

| Occupation | Medallist; engraver |

| Signature | |

| |

William Joseph Taylor (1802 - March 1885) was a British medallist and engraver who produced a wide variety of medals and tokens throughout his career, including the majority of medals and tokens produced in London, as well as a notable enterprise in Australia which attempted to establish the continent's first private mint.

Biography[]

William Joseph Taylor was born in Birmingham in 1802.[1] In 1818 Thomas Halliday employed him as an apprentice and was the first die-sinker to be trained by Halliday.[2] From 1 November 1820 onward, his wage was eight shillings per week.[2] In 1829 Taylor moved to London and set up his own business as a die-sinker, engraver and medallist.[2] The first workplace was 5 Porter Street in Soho, then he moved back to Birmingham and set up premises at 3 Lichfield Street. By 1843 it was time for the premises to move once more to 33 Little Queen Street, Holborn; in 1869 they moved to 70 Red Lion Street.[2]

Taylor died at 70 Red Lion Street in 1885.[2] His sons Theophilus and Herbert took over the business which operated until circa 1908, although Theophilus left in 1892.[2] Herbert Taylor sold the business to John Finches in 1908.[3]

Career[]

Whilst the majority of his work was in London, Taylor did work in other British locations: Eleazar Johnson was his agent in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire;[4] he also produced tokens for the Grantham auctioneer Escritt's (and his sons produced for the later partnership Escritt & Barrell).[3] He also collaborated to produce token currency in Australia.[5]

During his career, Taylor collaborated with William Webster, who issued a brass token designed and produced by Taylor.[1][6] One of Taylor's employees was W. E. Bardelle, a medallist, who worked for him for most of his life.[1] Another colleague was the painter and engraver , who modelled Taylor's masonic medal of Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, in 1843.[1]

Taylor is known for purchasing and re-using dies, including those of Matthew Boulton's mint at Soho, Birmingham.[3][7]

Medals[]

Taylor was a prolific engraver of medals, producing commemorative medals for over sixty organisations.[8] His firm appears to have produced virtually all the medals in London during the mid-nineteenth century.[6] He also issued a medal for the Melbourne Regatta in 1868.[9]

Organisational medals[]

He produced commemorative medals for the first congress of the British Archaeological Association in 1844 in silver (12 shillings) and bronze (6 shillings).[8][10] He designed a prize medal for the Royal Photographic Society.[11] This medal featured a bust of Prince Albert on the obverse, with a motif of the 'Chariot of the Sun' on the reverse.[12] He produced prize medals for the Royal Microscopical Society, featuring John Quekett on the obverse and a wreath with a blank space for a name on the reverse.[13] Smaller organisations included: Crystal Palace Choir;[14] the Arial Club, featuring a swimmer on the obverse;[15] for the London Swimming Club;[16] for John o'Gaunt's Bowmen;[17] for Sydenham Industrial Exhibition.[7]

Taylor also worked internationally, engraving a medal for the Timaru Agricultural & Pastoral Association, New Zealand, which featured a cow, a horse, a sheep and a pig on the obverse.[18]

Commemorative medals[]

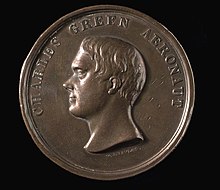

Taylor designed the medal commemorating the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843,[19] as well as a medal commemorating Charles Green's balloon flight from London to Weilberg in 1836.[20] He also produced a bronze medal commemorating the coronation of Queen Victoria.[21]

In 1851, Taylor produced commemorative medal for the Great Exhibition by striking them inside Crystal Palace itself and supposedly producing 400,000.[22]

Memorial medals[]

Memorial medals were also produced by Taylor - he produced one such piece, in the style of Pistrucci, as a memorial to Taylor Coombe, who was Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum.[23] He engraved a medal of William Carey[24] for another London medallist, W Griffin, who he also produced a temperance medal for,[25] as well as another featuring St Luke.[26] He engraved a medal of James William Gilbart, banker, who appears to have commissioned the work as a form of publicity to celebrate both his and the banks achievements.[27][28]

Generic medals[]

Taylor also produced general medals, which could be engraved by the purchaser. One example is a school prize medal issued by Palmer House School in Margate.[29][30] Another is a medal engraved by Taylor, ordered by the London Corporation as the Mathematical Prize for the City of London School.[31] One design was used and adapted for both the Arial Club and the Thames Regatta,[32] as well as for the Alliance Club whose competitions took place in the Serpentine.[33] He also re-issued medals at the request of benefactors, such as a Trafalgar, initially commissioned by industrialist Matthew Boulton.[34]

Tokens[]

Taylor also produced tokens for a variety of businesses and organisations, in Britain and abroad including: taverns, the military, railways and auctioneers.

Australia: the 'Kangaroo Office'[]

The Kangaroo Office was intended to be Australia's first privately run mint.[35] Taylor had realised that gold could be purchased from the Ballarat goldfields at reduced prices and potentially used to mint gold coins and release them for their higher value in London.[36] These coins looked more like weights, so they could bypass currency laws and restrictions; their dies were dated 1853.[35] In order to raise the money for the venture, Taylor formed a partnership with colleagues Hodgkin and Tyndall - together they raised £13,000 to cover costs and initial outlay.[35] They chartered a vessel, called The Kangaroo, to transport the press, the dies and two employees, Reginald Scaife and William Brown to Australia.[35] They arrived at Hobsons Bay on 23 October 1853, unfortunately the press was too heavy to move and Scaife and Brown had to dismantle it in order to transport it to the site of the new mint.[35]

The office began minting gold coins in May 1854.[35] These coins featured a kangaroo on the obverse and the words PORT PHILLIP and AUSTRALIA on the rim; the reverse showed the weight and the words PURE AUSTRALIAN GOLD.[35] One complete set was displayed at the Melbourne Exhibition in 1854, but it is unknown how many sets were produced.[35]

One of the issues that beset the enterprise was the fact that the price of gold increased in Australia, after the beginning of the venture.[35] This was coupled by an increase in the number of sovereigns in circulation in England, which meant there was less demand for gold there than had been anticipated.[35] In 1855, Taylor changed course and minted a sixpence in gold, silver and copper.[35] He then produced a four pence coin and a two pence coin in copper.[35] The two pence featured Britannia on the obverse and a kangaroo on the reverse, under which was signed "W J Taylor Medallist to the 1851 Exhibition".[5] Despite this, the office had substantial losses and closed in 1857.[35] The press was purchased by Thomas Stokes and remained in Australia.[9]

However, Taylor did retain some trade in Australia and New Zealand, issuing private tokens for companies, including Melbourne businessmen John Andrew and A.G. Hodgson.[9]

British tokens[]

Indeed, he appeared to have almost had a monopoly on London's tavern tokens in the mid-nineteenth century.[3] Early tokens, produced from 1844-5 were of a higher quality than the standardised form of copper token they became later.[37] Public houses who Taylor issued tokens for included: the Horns & Chequers in Limehouses;[38] St Helena Gardens in Rotherhithe;[39] the General Napier in Pimlico;[40] The Florence - Billiard & Skittle Rooms;[41] Middlesex Music Hall;[42] Marylebone Music Hall;[43] the Old Welsh Harp Inn;[44] Audinet Restaurant;[45] the Traveller's Rest in Shepherd's Bush;[46] the Downham Arms, Islington;[47] the Blue Bull, Grantham.[3] He produced canteen tokens for the Honourable Artillery Company,[48] and for the 37th Middlesex Regiment's Camp.[49] His tokens were used as railway tickets used in the north-east.[50]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "William Joseph Taylor - Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951". sculpture.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Biographical dictionary of medallists : coin, gem, and seal-engravers, mint-masters, &c., ancient and modern, with references to their works B.C. 500-A.D. 1900". Wellcome Collection. p. 41. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Whitmore, John (2009). "AUCTIONEERS' TOKENS" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 79.

- ^ WAGER, ANDREW (2006). "Review of Public House Tokens In England and Wales c.1830-c.1920". The Numismatic Chronicle. 166: 478–480. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 42666436.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "WJ Taylor medalist to the Great Exhibition token".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hawkins, R. N. P. (1960). "MINOR PRODUCTS OF BRITISH NINETEENTH-CENTURY DIESINKING" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "1873 Sydenham Industrial Exhibition Bronze Medal, Awarded to George Early for Furniture. Dies by W.J. Taylor. Unc. With Original Box". Jacob Lipson Rare Coins. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Keen, Laurence (1999). "A Note on the Medals of the British Archaeological Association". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 152: 172–176. doi:10.1179/jba.1999.152.1.172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "W.J.Taylor, Mint, London, United Kingdom". Museums Victoria Collections. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | BAA". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Silver medal awarded by the Royal Photographic Society to T R William, 1864 | Science Museum Group Collection". collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "Explore the Royal Collection Online". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "Medal of John Quekett in Leather Case, by W.J. Taylor, London, 19th Century".

- ^ "medal | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | Arial Club". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Long Distance Swimming Club Medals.1860-1900. - Life Saving & Swimming Medals". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | Bowmen". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Timaru Agricultural & Pastoral Association Medal | Taylor, William Joseph | V&A Search the Collections". V and A Collections. 2020-10-02. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "Thames Tunnel opening commemorative medal, 1843 | Science Museum Group Collection". collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "Charles Green Aeronaut | Science Museum Group Collection". collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | Victoria". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Medals of the Great Exhibition, 1851 – DCM Medals". Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ Walker, John (1953). "The Early History of the Department of Coins and Medals". The British Museum Quarterly. 18 (3): 76–80. doi:10.2307/4422438. JSTOR 4422438.

- ^ "medal | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | W Griffin". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | St Luke". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | J W Gilbart". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Barnes, Victoria; Newton, Lucy (2017). "Constructing Corporate Identity before the Corporation: Fashioning the Face of the First English Joint Stock Banking Companies through Portraiture". Enterprise & Society. 18 (3): 678–720. doi:10.1017/eso.2016.90. ISSN 1467-2227. S2CID 148634636.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | Palmer House". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Palmer House School Margate 1873 | Margate History". margatelocalhistory.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Blades, William (1870). "On Some Medals Struck by Order of the Corporation of London". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society. 10: 56–64. ISSN 2054-9172. JSTOR 42680869.

- ^ "medal | British Museum | Thames Regatta". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ McLACHLAN, R. W. (1879). "Canadian Numismatics. French Regime". American Journal of Numismatics, and Bulletin of the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society. 14 (2): 41–45. ISSN 2381-4586. JSTOR 43584599.

- ^ "The Fitzwilliam Museum - Home | Collections | Coins & Medals | Collection | Watson Medals Catalogue | Watson Medals Catalogue Home". www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk. 2007-03-06. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Coinworks. "Circa 1854 - Port Phillip Kangaroo Office". coinworks.com.au. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ Sharples, John (2006). "The Australasian Tradesmen's Tokens Project, The James Nokes Proof Halfpenny and Problems of the Kangaroo Office" (PDF). Journal of the Numismatic Association of Australia. 17.

- ^ Courtney, Yolanda (2000-06-01). "Pub Tokens: Material Culture and Regional Marketing Patterns in Victorian England and Wales". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 4 (2): 159–190. doi:10.1023/A:1009599504245. ISSN 1573-7748. S2CID 141205751.

- ^ "token | British Museum | Horns & Chequers". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "admission-ticket | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "General Napier token".

- ^ "medal | British Museum | The Florence". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "refreshment-ticket | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "theatre-ticket | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "token | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "token | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "token | British Museum | Traveller's Rest". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "token | British Museum | Downham Arms". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "canteen token | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "token | British Museum | 37th". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "ticket | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- 1802 births

- 1885 deaths

- Medallists

- English engravers

- People from Birmingham, West Midlands