William Pitt (architect)

William Pitt | |

|---|---|

Portrait as Mayor of Collingwood in 1891 | |

| Born | 4 June 1855 Melbourne, Victoria |

| Died | 25 May 1918 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Princess Theatre, St Kilda Town Hall, Queens Bridge, Bryant and May Factory, Wellington Opera House, Rialto Buildings, Olderfleet Buildings, Victoria Brewery. |

William Pitt (4 June 1855 – 25 May 1918) was an Australian architect and politician. Pitt is best known as one of the outstanding architects of the "boom" era of the 1880s in Melbourne, designing some of the city's most elaborate High Victorian commercial buildings. He worked in a range of styles including Gothic Revival, Italianate, French Second Empire, and his own inventive eclectic compositions. He had a notable second career after the crash of the 1890s, becoming a specialist in theatres and industrial buildings.[1]

Early life[]

William Pitt was born in 1855 in Melbourne[2] two years after his parents emigrated to Australia from Sunderland in England. His father, also William Pitt, ran some of the most notable cafes in Melbourne and was a practising artist. Raised in the suburb of St Kilda, he was educated at the Hofwyl School in St Kilda [1] later attended George Henry Neighbour's college in Carlton.[2] He later moved to the suburb of Abbotsford.

Career[]

In 1875 Pitt was articled to the architect George Browne, who was something of a prodigy himself, designing the Rupertswood mansion, Her Majesty's Ballarat and The Theatre Royal on Bourke Street in the early 1870s, when he was in his mid 20s.[3]

Pitt began his own architectural practice in 1879 at the age of 24 after winning the competition for the Melbourne Coffee Palace Bourke Street (between Swanton and Russell Streets). His design of an elaborate Renaissance Revival style facade over five storeys set the tone for the level of detail he would lavish on his subsequent boom era designs.[2]

Competition wins marked the success of his early years, winning that for an equally elaborate Renaissance Revival Premier Permanent Building Society (1882), and the Falls Bridge (Queens Bridge) in the same year[4](neither was built to his design),

His first prize winning entry in 1883 for "Our Lodgings" (later Gordon House) in Little Bourke Street, was an exception to his generally elaborate designs, being instead in an austere Tudor mode suitable for housing for the poor.[5]

Pitt's theatre work began with one of this best known buildings, and the most elaborate 19th century theatre exterior to survive in Australia, the Second Empire style Princess Theatre (1886) in Spring Street. The elaborate dome-like Mansard roofed pavilions, the each topped by crown-like cast iron capping, still makes a striking statement in Spring Street, and the sumptuous marble stair and elaborately ceilinged circle foyer are the finest Victorian era theatre interiors to survive in Australia (the auditorium itself was replaced in 1922).

Perhaps following this success, in 1887, Pitt was appointed vice-president of the Victorian Institute of Architects.

His largest and most ambitious commission followed soon after, the Federal Coffee Palace at the south-west corner of King Street and Collins Street. While he received a second prize for his design, he was allowed to collaborate with the winners, Ellerker & Kilburn and the result was a composite design. The massive elaborate building synthesises Renaissance revival, French Second Empire and French Renaissance elements and was both hailed and criticised for its extraordinary ebullience. Completed in 1888, the enormous building later came to epitomise the speculative land boom which was "Marvellous Melbourne" of the late 1880s.

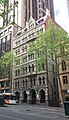

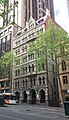

Pitt could produce equally elaborate work in variations of the Gothic revival style. The Flemish Gothic Olderfleet (1888) and the Venetian Gothic Rialto Buildings (1889) a few doors down in Collins Street are essential elements of the Rialto group, the most elaborate and cohesive commercial Victorian Streetscape in Melbourne. His other greatest work in Collins Street is the lavishly detailed Gothic Revival Stock Exchange (1888), complete with rose window, spire and vaulted 'Cathedral Room' on the ground floor. In 1890, he added the Gothic Revival Safe Deposit Building around the corner on Queen Street.

His polychromatic design of the very long, 3 storeys high Denton Hat Mills (1888) in Abbotsford, Victoria began his specialisation in industrial design. He also designed Brunswick Town Hall in 1889.

Tower House (1891), once a landmark on the corners of Spring and Flinders Streets, was a fairly standard Italianate body, topped by a steeply pitched Gothic roof and spiky corner tower with a witches hat roof.

One of his rare residential commissions was Collendina, near Corowa NSW, built for Henry Hay Esq. in 1891, dominated by an elaborate double level cast-iron verandah.[6]

In 1892, he showed his passionate support for the Collingwood Football Club by designing a grandstand for Victoria Park for free.

Like so many others, Pitt suffered a massive financial setback during the financial crisis of 1893. Not only did he lose commissions as building work practically ceased, but other investments failed.[2]

He kept his practice going however, and began a second career, designing a range of building types in the then fashionable styles, specialising in theatre and industrial projects.

He is responsible for much of three of the most prominent and architecturally distinctive inner city industrial complexes in Melbourne in the Edwardian era.

The first was the distinctive red-brick castellated design of additions and alterations to the Victoria Brewery on Victoria Parade in East Melbourne. The first section built to his design was completed in 1896, and he went on to design many additions into the 1910s creating the large walled complex seen today.[7]

Pitt worked for the Collinswood-based Foy & Gibson for much of his professional life, starting in the late 1880s, and this also sustained him after the crash. He designed many of the still extant buildings between 1896 and the 1910s that form the huge complex of large-scale factory buildings, whose red-brick rhythmic vertical piers and large cornices dominate Oxford and Cambridge Streets in Collingwood.

A third major commission was the enormous main building of the Bryant and May Factory, built in 1909 on Church Street in inner suburban Richmond, also in a red-brick piered format, but with more lively expression than Foy & Gibson, and a street facade that included Art Nouveau details.

His theatre work included numerous new theatres such as the New Opera House (later the Tivoli), Bourke Street (1900, demolished), the King's Theatre, Russell Street, Melbourne (1908, demolished), the Theatre Royal, Adelaide (1914, demolished), and in New Zealand the Opera House, Wellington (1914). These were designed in a range of styles, though the Tivoli was by far the most inventive, featuring a red brick facade with exotic Moorish horseshoe arches, topped by a globe. The others were all relatively simple classical designs, with pilasters and pedimented facades, and grand but not overly elaborate interiors.

He also renovated many older theatres, such as His Majesty's Ballarat, where he inserted new balconies in 1898 and Her Majesty's, Pitt Street, Sydney (1903, demolished), where he inserted a new interior following a fire, and a completely new interior for the Theatre Royal, Hobart in 1911. His work even extended to one of the first luxury cinema buildings in Melbourne, the Hoyts De Luxe in Bourke Street (1915, facade remains under later cladding). Some declared him at the time to be the greatest theatre architect in Australia.[8]

Another rare foray into residential architecture in this period was Avalon (1903) at 70 Queens Road, demolished 2008.[9]

Other projects include the Victorian Racing Club (1910), Collins Street (demolished), and a number of hotels such as the Charles Hotham Hotel (1912), on the corner of Spencer and Flinders Streets.

Premier Permanent Building Society 1882. Demolished.

Melbourne Coffee Palace in 1882. Demolished in the 1960s.

Princess' Theatre Restored 1980s

The Federal Coffee Palace, one of Pitt's most ambitious designs. Demolished in 1972.

Olderfleet buildings

Old Safe Deposit Building

Old Rialto Building

Former Melbourne Stock Exchange

The Denton Hat Mills

Victoria Brewery

Facade illustration of the New Opera House, Melbourne, 1900

Bryant & May Factory, from Church Street, Richmond

Sir Charles Hotham Hotel

Avalon. A rare residential commission. Derelict in 2008, demolished in March 2011.

Public life[]

Like many successful men of this period, Pitt took an active part in public life.

He was an active member of the Australian Natives' Association, the Freemasons, a patron of the Collingwood Football Club, and a member of the Melbourne Harbor Trust from 1894 to 1913 (chairman, 1901–05).

He was a staunch protectionist and a vocal supporter of the Australian Federation Movement,[10] and acted on these views while a member of the Victorian Parliament. He sat in the Victorian Legislative Council from 1891 to 1910, first for North Yarra Province until 1904, then Melbourne East Province until 1910.

He was also active in local politics, elected to the City of Collingwood council in 1888, where he was the mayor for 1890, before retiring from council in 1894. In 1891–92 he sat on the Melbourne Board of Works as the representative of the City of Collingwood.[2]

Personal life[]

Pitt married Elizabeth Mary Liddy on 23 October 1889 at St Peter's Church. On 25 May 1918, he died at home in Abbotsford, and was buried in St Kilda General Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, three daughters and a son.[2]

References[]

- ^ Goad, Philip (2012). Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture. Cambridge University Press. p. 543.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition

- ^ Leech, Judith. "Pitt & Browne as Architects". Theatre Heritage Australia Inc. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ "The Falls Bridge Designs". The Argus. 21 February 1882. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "Gordon House". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Victoria. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ "Historic homestead for sale". Border Mail. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ "Former Victoria Brewery". Victorian HeritageDatabase.

- ^ http://www.hermaj.com/CMS/index2.php?option=content&task=view&id=10&pop=1&page=0

- ^ "Historic Avalon Mansion Demolished". realestatesource.com.au. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Re-Member (Former Members)". State Government of Victoria. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

External links[]

Media related to William Pitt (architect) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Pitt (architect) at Wikimedia Commons

- 1855 births

- 1918 deaths

- Australian federationists

- Architects from Melbourne

- Politicians from Melbourne