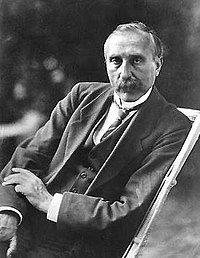

William Ritter (writer)

William Ritter (31 May 1867 – 19 March 1955) was a Swiss novelist, critic and painter.

Life[]

Ritter was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland on 31 May 1867,[1] the son of Guillaume (also known as Wilhelm) Ritter (1835–1912), a French architect and hydraulic engineer[2] from Soultz responsible for enabling a supply of fresh water to La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1887,[3] and Josephine Ducrést, a Swiss woman from Berne.[4] Ritter went to the Jesuit school in Dole,[5] followed by the Collège latin in Neuchâtel from 1881, then in 1885 he enrolled in the Academy of Neuchâtel.[1]

As a young man Ritter was a devotee of Richard Wagner, and he made contact with French Decadent circles in Paris in his early twenties.[1] After he graduated from the Academy he travelled extensively in Europe, first in the west – Paris, Vienna, Munich – then in the east (Czechoslovakia, Poland, Montenegro, Romania and Slovakia), gathering material for his novels.[1] The near East provided Ritter with a taste of the exoticism, comparable to the Istanbul described by Pierre Loti,[6] that was a particular fascination to figures within the Decadent movement in Paris, particularly the aesthete Robert de Montesquiou and Sâr Péladan.[6]

Ritter went to Prague in 1888 to learn German, then studied the history of art and music at the University of Vienna for a term, taking a course in harmony from Anton Bruckner.[4][6] In 1889, his friend the French architect Léon Bachelin invited him to Bucharest, the first of a ten-year-long series of repeated trips that Ritter undertook to the east and the Balkans. The next year Ritter went to Transylvania with Nicolae Grigorescu, the painter. Tours in Albania on horseback with his friend Marcel Montandon in 1893 and a traverse of the Carpathians in 1898 by foot followed.

In 1903, during a walking trip across Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia, he met Janko Cádra, who became his companion and secretary until his death in 1927, and he lived with him variously in Prague (for a year between 1904 and 1905),[7] Munich, Monruz (in Neuchâtel), Slovakia and Romania.[6] In Munich Ritter served as tutor to Prince and Princess Rupprecht for four years,[6] the prince becoming the last heir apparent to the Bavarian throne in 1913.

After the First World War, Ritter spent much time in the newly created Czechoslovakia, but, as a homosexual aesthete and Catholic conservative he felt disillusioned with this progressive and modern democratic country that had thrown off the shackles of empire.[6] Following Cádra's death in 1927, Ritter started a relationship with another young Slovak, Josef Červ. In 1930–1 Ritter was appointed as a lecturer in French at the University of Brno.[6]

Ritter died on 19 March 1955 in Melide.[1]

Writings[]

Ritter has been called a "graphomaniac",[6] and his writings are not easily categorised; many of his unpublished works are simply called "Notes". His first works were inspired and comparable to the avant-garde works of the French Symbolists, but over the course of his life his art criticism became increasingly reactionary, dismissing innovations such as Expressionism and Cubism.[6]

Music criticism[]

Ritter was the correspondent for the Parisian literary review Mercure de France in Prague from 1904 to 1905, writing on musical matters, and 1907 he wrote the first French-language book on Bedřich Smetana.[7]

Ritter is well known today for his writings on and support for Gustav Mahler. Ritter was initially an opponent of Mahler, like many of Mahler's critics in Vienna, on racial and antisemitic grounds.[8] Of a performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 4 in Munich on 1901 he wrote, "Jewish wit has invaded the Symphony, corroding it,"[9] and that the work was so "moist and persuasive, tantalizing and seductive" that it provoked "lewd glances in the concert halls, the salacious dribble at the corners of the mouths of some of the old men, and above all the ugly, whoring laughs of certain respectable women!".[10] Ritter converted to the Mahler cause after seeing the composer conduct his own Symphony No. 3 in Prague on 2 February 1904[11] and in time he became one of the composer's staunchest advocates, writing glowing reviews of the premieres of Mahler's Symphony No. 7 (in Prague, 1908)[12] and Symphony No. 8 (in Munich, 1910). Ritter viewed Mahler's music as symbolic of modern Vienna, in the same way as the architecture of Adolf Wagner and the painting of Gustav Klimt and Koloman Moser.[13]

As a keen Slavophile, Ritter also did much in the promotion of the music of Leoš Janáček.[14] Ritter had first had dealings with Janáček in 1912, agreeing to be a judge in a Club of the Friends of Art competition, but they did not meet until 1923.[14] They started corresponding in 1924, and in total 18 letters survive, including the last letter that Janáček wrote.[7] Ritter attended the rehearsal and premiere of Janáček's Glagolitic Mass in Brno in November–December 1927, and told the composer that it was best thing that he had ever written.[15] Janácek replied to a letter from Ritter about the premiere with the words: "The way you write about my work makes me red-faced."[15] The title of Janácek's incomplete Concerto for Solo Violin and Orchestra, Putovani dusicky (The pilgrimage of a little soul), bears a possible relation to Ritter's play L'ame et la chair (Soul and Body), the libretto of which Ritter offered to Janácek in 1924.[16] Ritter planned to write a book on Janáček, possibly the reason for the frequent meetings that the two had in July 1928, but none was ever written.[7]

Theory of culture[]

The debate about Swiss identity in Switzerland at the turn of the 19th–20th century concerned what constituted Swiss identity: geographical location or race – French, German or Italian. Ritter considered Swiss who spoke French had a Latin identity.[17]

Ritter's theory of culture had a profound influence on the thinking of the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who was a friend of Ritter in Munich, where they both lived, Ritter being something of a "mentor"[17] to Le Corbusier from 1910 to 1916, assuming the fatherly role that had previously been filled by the Swiss painter Charles l'Eplattenier.[18] Ritter's notion that identity was a product of rootedness in a particular location (provoking his ancillary dislike of rootless Americans, city-dwelling Germans and Jews), together with his lifelong affection for Slavs, made a deep impression on Le Corbusier, and was a decisive influence on his journey through the Balkans during his trip to the east in 1911, during which he studied Balkan vernacular architecture.[17]

Works[]

- Aegyptiacque (1891)

- Les dernières oeuvres de Johann Strauss (1892)

- Les chauves-souris du comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac (1893)

- Âmes blanches (1893)

- La Jeunesse inaltérable et la vie éternelle, légende roumaine, illustrations de l'imagier Andhré des Gachons (1895)

- L'art en Suisse (1895)

- Fillette slovaque. Le cycle de la nationaliti (1903)

- Leurs lys et leurs roses (1903)

- La Passante des quatre saisons (1904)

- Études d'art étranger (1906)

- "Magyars, Roumains et Juifs", Demain (Lyon) Vol. 1, No. 19 (2 March 1906), pp. 10–13.

- Smetana, par William Ritter (1907)

- Chronique tchèque (1907)

- Smetana (1907)

- Chronique tchèque. M. Josef Suk et sa symphonie "Asrael" (1907)

- Chronique tchèque (1907)

- La VIIe Symphonie de Gustav Mahler (1908)

- L'Entêtement slovaque (1910)

- M. Richard Strauss (1910)

- Haydn et la musique populaire slave (1910)

- La VIIIe symphonie de Gustave Mahler (1910)

- Un maître de la symphonie. M. Gustav Mahler (1911)

- A propos du "Pierrot lunaire" d'Arnold Schönberg (1912)

- La "neuvième" de Gustave Mahler (1912)

- Recueil. Dossiers biographiques Boutillier du Retail. Documentation sur Louis III, roi de Bavière (1913)

- Article on L. Bakst in Czech (1913)

- Le Son lointain’‘ (Der ferne Klang), opéra de Franz Schreker (1914)

- Les Tendances de la musique en Tchécoslovaquie depuis la mort de Smetana (1921)

- Les Tendances de la musique en Allemagne et en Autriche depuis la mort de Wagner (1921)

- Texte (1923)

- Max Švabinský (1923)

- Max Švabinský, cent dessins. Texte de William Ritter (1923)

- La Moisson de Max Švabinský, histoire et esthétique d'un tableau (1929)

- La Moisson" de Max Švabinský, histoire et esthétique d'un tableau (1929)

- Notes (1976)

- Correspondance croisée, 1910–1955 (2014)

- Carnet de notes de voyage (2016)

Works on Ritter[]

- Tscherv, Josef, William Ritter, enfance et jeunesse, 1867–1889, Melida, 1958

- Tscherv, Josef, William Ritter 1867–1955, Bellinzona, 1971

- Rydlo, Jean-Marc, "Helvetus Peregrinus: William Ritter et la Slovaquie", Hispo (Bern), October 1989, pp. 7–20

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "William Ritter". hls-dhs-dss.ch. Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS). Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Guillaume Ritter". hls-dhs-dss.ch/. Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS). Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Brooks, H. Allen (1999). Le Corbusier's Formative Years: Charles-Edouard Jeanneret at La Chaux-de-Fonds. University of Chicago Press. pp. 217–18. ISBN 9780226075822.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Galmiche, Xavier (2004). "L'arrière-pays d'une ville incertaine. 'L'invention' de Prague et de la Tchécoslovaquie chez William Ritter". In Voisine-Jechova, Hana (ed.). L'Image de la Bohême dans les lettres françaises. Réciprocité culturelle des Français, Tchèques et Slovaques. Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne. pp. 45–56. ISBN 9782840502852.

- ^ "Fonds William Ritter". cdf-bibliotheques.ne.ch/. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Galmiche, Xavier. "Europe centrale et patries personnelles chez William Ritter". www.circe.paris-sorbonne.fr/. Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherches Centre-Européennes. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Janáçek, Leos; Tyrrell, John (2014). Intimate Letters: Leos Janáček to Kamila Stösslová. Princeton University Press. p. 361.

- ^ "William Ritter". mahlerfoundation.info. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Colli, Ilario (7 July 2015). "Mahler: The Double Man". Limelight. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Kroha, Lucienne (2014). The Drama of the Assimilated Jew: Giorgio Bassani's Romanzo di Ferrara. University of Toronto Press. p. 81. ISBN 9781442665064.

- ^ "Janko Cadra (1882–1927)". mahlerfoundation.info/. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Donald Mitchell, "Mahler in Prague" (2002). Mitchell, Donald; Nicholson, Andrew (eds.). The Mahler Companion. Oxford University Press. pp. 400–407.

- ^ Johnson, Julian (2009). Mahler's Voices: Expression and Irony in the Songs and Symphonies. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780195372397.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tyrell, John (2011). Janacek: Years of a Life Volume 2 (1914-1928): Tsar of the Forests. Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571268726.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wingfield, Paul (1992). Janácek: Glagolitic Mass. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780521389013.

- ^ Straková, Theodora (1997). Janáček's Works: A Catalogue of the Music and Writings of Leoš Janáček. Clarendon Press. p. 291. ISBN 9780198164463.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Passanti, Francesco (December 1997). "The Vernacular, Modernism, and Le Corbusier". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 56 (4): 433–451. doi:10.2307/991313. JSTOR 991313.

- ^ Vogt, Adolf Max (1998). Le Corbusier, the Noble Savage: Toward an Archaeology of Modernism. MIT Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780262220569.

- 1857 births

- 1955 deaths

- 19th-century Swiss writers

- 20th-century Swiss writers

- LGBT writers from Switzerland

- People from Neuchâtel