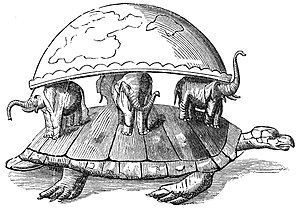

World Turtle

The World Turtle, also called the Cosmic Turtle or the World-bearing Turtle, is a mytheme of a giant turtle (or tortoise) supporting or containing the world. It occurs in Hindu mythology, Chinese mythology, and the mythologies of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. The comparative mythology of the World-Tortoise discussed by Edward Burnett Tylor (1878:341) includes the counterpart World Elephant.

India[]

The World Turtle in Hindu mythology is known as Akupāra (Sanskrit: अकूपार), or sometimes Chukwa. An example of a reference to the World Turtle in Hindu literature is found in Jñānarāja (the author of Siddhāntasundara, writing c. 1500): "A vulture, whichever has only little strength, rests in the sky holding a snake in its beak for a prahara [three hours]. Why can [the deity] in the form of a tortoise, who possesses an inconceivable potency, not hold the Earth in the sky for a kalpa [billions of years]?"[1] The British philosopher John Locke made reference to this in his 1689 tract, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which compares one who would say that properties inhere in "substance" to the Indian, who said the world was on an elephant, which was on a tortoise, "but being again pressed to know what gave support to the broad-backed tortoise, replied—something, he knew not what".[2]

Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable lists, without citation, Maha-pudma and Chukwa as names from a "popular rendition of a Hindu myth in which the tortoise Chukwa supports the elephant Maha-pudma, which in turn supports the world".[3]

China[]

In Chinese mythology, the creator goddess Nüwa cut the legs off the giant sea turtle Ao (simplified Chinese: 鳌; traditional Chinese: 鰲; pinyin: áo) and used them to prop up the sky after Gong Gong damaged Mount Buzhou, which had previously supported the heavens.[4]

North America[]

The Lenape myth of the "Great Turtle" was first recorded between 1678 and 1680 by Jasper Danckaerts. The myth is shared by other indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, most notably those of the Haudenosanee confederacy,[5] and the Anishinaabeg.[6]

The Jesuit Relations contain a Huron story concerning the World Turtle:

'When the Father was explaining to them [some Huron seminarists] some circumstance of the passion of our Lord, and speaking to them of the eclipse of the Sun, and of the trembling of the earth which was felt at that time, they replied that there was talk in their own country of a great earthquake which had happened in former times; but they did not know either the time or the cause of that disturbance. "There is still talk," (said they) "of a very remarkable darkening of the Sun, which was supposed to have happened because the great turtle which upholds the earth, in changing its position or place, brought its shell before the Sun, and thus deprived the world of sight."'[7]

In modern media[]

In the Discworld series created by Terry Pratchett, the world is said to be a flat plane sitting on top of four elephants astride the shell of a giant turtle named A'Tuin.

In the book Monday Begins on Saturday by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, a disc upon elephants on a turtle is said to have been discovered by a pupil who entered an ideal world of imagination.

In the book It by Stephen King, Pennywise's archenemy is a giant turtle named Maturin.

In the book A Wild Sheep Chase by Haruki Murakami, the nameless narrator references this idea.

The 1993 music video "Whatzupwitu", a duet by Michael Jackson and Eddie Murphy, features the world turtle as with an animation. A spinning globe is seen spinning atop elephants standing on the shell of a turtle swimming through sky. The introduction also features a clown seen through a puddle who says, "the elephant is dying".

In the 2021 episode "The Casino" of the show What We Do in the Shadows, the 800 year old vampire Nandor experiences cosmic dread when he learns that his belief in the World Turtle concept is wrong.

See also[]

- Turtles all the way down

- World Serpent

- World Tree

- Zaratan

- Torterra

References[]

- ^ Toke L. Knudsen, Indology mailing list.

- ^ Locke, John (1689). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book II, Chapter XXIII, section 2

- ^ Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, 15th ed., revised by Adrian Room, HarperCollins (1995), p. 1087. also 14th ed. (1989).

- ^ Yang, Lihui; An, Deming; Jessica Anderson Turner (2008). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6.

- ^ Why the World is on the Back of a Turtle - Miller, Jay; Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, New Series, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Jun., 1974), pp. 306–308, including further references within the cited text)

- ^ "Turtle Island | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

- ^ "Front Page". puffin.creighton.edu. 11 August 2014.

- Legendary turtles

- World-bearing animals

- Mythological archetypes