Yury A. Dmitriev

Yury A. Dmitriev | |

|---|---|

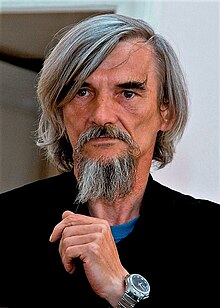

Yury Dmitriev, 2007 | |

| Native name | Юрий Алексеевич Дмитриев |

| Born | Yury Alexeyevich Dmitriev 28 January 1956 Petrozavodsk, Karelo-Finnish SSR, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics |

| Occupation | Human rights activist, researcher into deportation,and author imprisonment and executions in 1930s |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Citizenship | |

| Alma mater | Leningrad Medical College |

| Notable awards | Golden Pen of Russia (2005)

Gold Cross of Merit, Poland (2015) Honorary Diploma of the Karelian Republic (2016) Sakharov Prize, Moscow (2017) Moscow Helsinki Group award (2018) |

| Spouse | twice married |

| Children | Son Yegor, daughter Katerina (Klodt); adopted daughter Natasha |

Yury Alexeyevich Dmitriev (born 1956 in Petrozavodsk) is a civil rights activist and local historian in Karelia (Northwest Russia). Since the early 1990s, he has worked to locate the execution sites of Stalin's Great Terror and identify as many as possible of the buried victims they contain.[1][2]

On 13 December 2016 Dmitriev was arrested and charged with making pornographic images of his foster daughter, Natasha.[3][4] From the outset Dmitriev's colleagues declared the charges to be baseless and motivated by a determination to discredit the historian and his work. The closed trial attracted national and international attention and criticism.[5] On 26 December 2017, a second assessment by a court-appointed body of the photographs of his foster daughter concluded that they contained no element of pornography and had been taken, as the accused insisted, to monitor the health of a sickly child.[6]

After a psychiatric examination at the Serbsky Institute in Moscow,[7] the historian was released from custody on 27 January 2018 on condition that he did not leave Petrozavodsk. The charges against him were not dropped and the next court hearing was scheduled for 27 February 2018.[8] On 5 April 2018 the judge acquitted Dmitriev on two charges relating to the photos of his adopted daughter Natasha, removing the threat of nine years' imprisonment, demanded on 20 March by the prosecution.[9] The court found Dmitriev guilty of the lesser and separate offence of possessing a firearm. After more than a year in custody, Dmitriev was sentenced to three further months restriction of liberty, meaning that he has to report twice a week to the city prison. On 13 April 2018, the Petrozavodsk city prosecutor, Yelena Askerova, submitted a formal appeal to the court against the acquittal of Yury Dmitriev on all but one charge.[10] Dmitriev was again arrested in June 2018, supposedly for breaching the terms of his release in January. On 14 June the Supreme Court of Karelia overturned the April verdict and ordered a retrial. Later additional charges were added and Dmitriev again underwent a psychiatric examination.

On 22 July 2020, Dmitriev was convicted of sexual assault against his adopted daughter on evidence the nature of which was finally revealed after the trial ended.[11] The judge imposed a sentence one quarter the length of that recommended in the Criminal Code. Prosecution and defence have appealed, respectively, against the sentence and the verdict. The historian will walk free in mid-November 2020 if neither appeal is upheld.

When Dmitriev was first arrested at the end of 2016 he was finishing nine years of work on a Book of Remembrance that would name over 64,000 of the deported "special settlers" of the 1930s whose descendants make up 25-30% of those now living in Karelia.[12]

Childhood and early adult years[]

Yury Dmitriev spent his first year in a Soviet orphanage. In 1957 he was adopted by a childless army officer and his wife; he found out he was not their child at the age of 14.[13] His father was posted to East Germany, and Yury spent part of his childhood in Dresden.[14]

He began but did not finish a course at the Northwest Health Department of the Leningrad Medical College.[15] During the Gorbachev years, Dmitriev was a member of the Karelian People's Front, and served between 1988 and 1991 as an aide to USSR People's Deputy Mikhail Zenko. It was then that he first encountered mass graves of those shot in the 1930s.[16]

Restoring the names[]

Dmitriev is known for his part in the discovery and investigation of two major burial sites, Sandarmokh and Krasny Bor, and their subsequent transformation into "informal" memorial complexes.

Yekaterina Klodt, Dmitriev's daughter by his first marriage, has described her father's commitment to his work. "I often asked him why he continually sat at the computer, writing or copying something out," she told Gleb Yarovoi. Dmitriev answered: "I do not know who I was in a past life, but I understand the meaning of my life now and I know that I must do this." As she grew older Yekaterina would frequently tell him to take a break—how much longer would he go on with these lists? "I can't stop," Dmitriev replied, "I must finish the book, people are waiting for it."[17] Dmitriev's life consisted, for year after year, of winters spent in the archives followed by summers scouring the forested areas around particular cities and towns with Witch (Vedma), his Alsatian, hunting for possible burial sites.[18]

At first Dmitriev was junior partner to Ivan Chukhin (ru: Чухин, Иван Иванович), a deputy of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet and State Duma (1990-1995),[19] and the first chairman of the Memorial Society in Karelia.[20] Chukhin felt compelled to engage in the work because his own father had been involved in acts of repression under Stalin.[21] When Chukhin, a retired police officer, was killed in a car accident in May 1997 Dmitriev carried on alone. On 1 July 1997, with members of St Petersburg Memorial, Dmitriev located a massive killing field, 12 kilometres from Medvezhyegorsk, that subsequently acquired the name of Sandarmokh; some weeks later, guided by local inhabitants, he confirmed the identification of the Krasny Bor execution site, 20 km from Petrozavodsk.[22]

Sandarmokh contains over 9,000 of Stalin's executed victims of more than 50 Soviet and other nationalities.[23] Drawing on information from the archives, Dmitriev identified the nine thousand men and women shot at Sandarmokh as follows:[24]

"3,500 were inhabitants of Karelia, 4,500 were prisoners working for the White Sea - Baltic Canal, and 1,111 were brought there from the Solovki "special" prison. Alongside hard-working peasants, fishermen and hunters from nearby villages, writers and poets, scientists and scholars, military leaders, doctors, teachers, engineers, clergy of all confessions and statesmen found their final resting place there."

In 2003, in addition to his Books of Remembrance, Dmitriev also published a collection of documents about the construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal and the fate of the numerous prisoners and "special settlers" engaged in its construction.[25]

Recognition at home and abroad[]

As a result of Dmitriev's activities, he was appointed secretary of the Petrozavodsk Commission for Restoring the Rights of Rehabilitated Victims of Political Repression and in 2002 became (and remains) a member of the organisation of the same name at the republican level, covering all of Karelia. He is a member of the Karelian branch of the Memorial Society, and in 2014 became its chairman.[26]

From 1998 to 2009, Dmitriev headed the Academy for the Defence of Socio-Legal Rights, a Karelian human rights NGO.[26] As president of that body, in 2002, Yury Dmitriev wrote to the then head of the Karelian republic, Sergey Katanandov, objecting to the proposal by the Karelia Council of Veterans to put up a statue in Petrozavodsk to Yury Andropov. (KGB chairman from 1967 to 1982, Andropov headed the Komsomol in Karelia during the Great Patriotic War, from 1940 to 1944.) Katanandov did not reply to Dmitriev's letter and the 10-foot-high memorial to Andropov was erected. The decision, commented Dmitriev, reflected the nation's attitude to its recent history: "We don't know the past, and we don't want to know."[27]

In 2005, Dmitriev was awarded the new "Golden Pen of Russia" prize for his publications.[28]

In 2015, he received the Gold Cross of Merit from Poland for his work in locating mass burials at Sandarmokh and on Solovki, and identifying the victims they contained: ethnic Poles in the Soviet Union were one of the nationalities targeted during the Great Terror.[29]

In 2016, Dmitriev was awarded an Honorary Diploma of the Karelian Republic by the administration of the new head of Karelia, Alexander Hudilainen (Худилайнен, Александр Петрович).

On 31 December 2017, Yury Dmitriev was one of 16 journalists, bloggers, writers and historians, imprisoned or otherwise persecuted by the authorities, who were recognised at the annual Sakharov awards for "Journalism as an Act of Conscience".[30]

Criminal prosecution[]

In late 2016, Dmitriev was arrested on charges of child pornography. In 2018, he was acquitted of those charges. Later in 2018, he was arrested again for charges of sexual assault. In 2020, he was found guilty of those charges and sentenced to 3 and a half years in prison.[31] This sentence was later increased to 13 years. [32]

His defense team consider the charges to be fabricated, a misinterpretation of what little evidence the investigators have found. There is also concern about the prospects for a fair trial. On 10 January 2017 a 13-minute segment of the news programme entitled "What does Memorial have to hide?" on a national TV network Rossiya-24 showed the allegedly pornographic photographs Dmitriev had taken of his foster daughter Natasha.[33] The defence team believes they were leaked to the media by the investigators, although as evidence in a forthcoming trial they were sub judice.[34]

The explanation offered by Dmitriev for the existence of the 140 photographs, 9 of which are claimed by the prosecution to be pornographic, is that they record the improving health of a neglected and under-nourished little girl from a children's home, whom he and his second wife had taken into their care. He stopped keeping this photographic record in 2015.[35]

It was subsequently revealed by the defence that there were only three such photographs: copies of two photos boosted the total to nine.[36]

When charges were brought against the imprisoned Dmitriev in early 2017 it became clear that he had many supporters.[37] By early July, an Internet petition in his defense had drawn over 30,000 signatures in Russia and elsewhere.[38]

Start of the Trial[]

After months in police custody, his trial began on 1 June 2017.[39] As with other trials in Russia concerning sexual offences against minors, neither press nor public were admitted to the hearings at the Petrozavodsk City Court.[40]

On 11 July, four expert witnesses testified on behalf of the defence, casting serious doubts on the interpretation of the evidence by the prosecution and its experts. Dmitriev's attorney Victor Anufriev announced that the hearings had ended for the time being and would resume on 1 August. He expressed the hope that his client could address the court on 22 August and that a verdict would be delivered by 1 September 2017.[41]

Thanks to the persistence of the defence, however, the trial continued. On 15 September 2017, the court agreed to submit the photographic evidence to other experts, after the defence had petitioned four times for such a decision.

New assessment of photographs[]

The alternative organisations proposed for this task, first by the prosecution and then by the judge, proved to be obscure private firms without the legal right to act as forensic experts.[36]

The hearing scheduled for 18 October was postponed because the new experts were not ready to present their fresh assessment of the same 9 pornographic photographs. A hearing was held on 25 October but the assessment of the photographs was still not ready.[42] On 26 December 2017, the new court-appointed body finally presented the findings of its experts that there was no element of pornography in the photographs taken by Dmitriev and concluded that their purpose was to monitor the health of a sickly child.[43]

Second psychiatric assessment[]

That same day the Petrozavodsk City Court ruled that Yury Dmitriev should undergo a second psychiatric assessment at the Serbsky Center in Moscow, and that a third assessment of the nine photographs be made by the same body. This decision caused some concern. Dmitriev had already been subject to psychiatric assessment in Petrozavodsk and there had been signs of a revival at the Serbsky Center of its well-documented Soviet-era use as an instrument of political punishment.[44]

On 27 December 2017, the court changed the measure of restraint imposed on Dmitriev. After more than a year in custody at the city's Detention Centre No 1, he would be released on 28 January 2018 (his 62nd birthday), on condition that he did not leave the country.[45] On 28 December, without notifying his defence attorney, the court had Dmitriev flown under escort to Moscow where he was taken to the Serbsky Center to begin assessment.[46] On 30 December, Dmitriev's son delivered food for his father to the Serbsky Center.[47]

Release and resumption of trial[]

On 27 January, Dmitriev was released from custody and allowed to return to his home, on condition that he did not leave the city of Petrozavodsk.[48][49] On 20 March, the city prosecutor Askerova reaffirmed the accusations against him and demanded 9 years of prison in a severe regime colony. The next court hearing is scheduled for 22 March 2018.

Acquittal and appeal[]

On 5 April 2018, Dmitriev was acquitted of the child pornography charges by Judge Marina Nosova at the conclusion of his trial at the Petrozavodsk City Court. She found him guilty of possessing parts of a shotgun and sentenced him to three months probation plus community service. Dmitriev had denied all the charges.[50]

Novaya Gazeta newspaper commented: "The decision was unprecedented for Russian justice where the percentage of acquittals does not exceed the statistical margin of error."[51] In trials without a jury, the percentage of acquittals in the Russian judicial system is now markedly less than 1% of the total.[52] The result in the Dmitriev Case, therefore, was an achievement against the odds. (In trials where the case is heard before a jury, the proportion of acquittals was higher, around 20% of the total in 2009.)[53]

On 13 April 2018, the Petrozavodsk city prosecutor, Yelena Askerova, submitted a formal appeal to the court against the acquittal of Yury Dmitriev on all but one charge.[10] This appeal was accepted by the Supreme Court of Karelia and a hearing was set for Thursday, 14 June. Dmitriev's defence attorney, Victor Anufriev, submitted an appeal against his client's conviction for possessing parts of a firearm.[54] On 14 June 2018, the acquittal was overturned by the Supreme Court of Karelia.[55]

Reaction to trial[]

Journalist Maria Eismont wrote that the trial of Yury Dmitriev in Petrozavodsk was "the most important thing happening in Russia right now".[56]

The dramatist and poet Alexander Gelman commented:[57]

"This trial has helped us recognise a remarkable man. It is a barbaric way of discovering good people, but in Russian society it has proved very effective. In this sense, the trial has done something worthwhile."

By early December 2017, over seventy video clips of famous Russians speaking in Dmitriev's defence—writers, musicians, priests, historians, film-makers, actors—had been posted on a variety of social media and reposted to his supporters' Facebook page and to the Dmitriev Affair website.[58] Among them were TV presenter and literary critic Alexander Arkhangelsky,[59] Natalya Solzhenitsyn,[60] film director Andrey Zvyagintsev, and the sculptor-designer of the Wall of Sorrow monument, Georgy Frangulyan, who commented: "What has happened [to Dmitriev] is appalling, it's tragic".[61]

New arrest, a new charge[]

On 28 June 2018, Yury Dmitriev was arrested again, apparently for breaking the terms of his release in April: he was stopped by police, travelling out of the city of Petrozavodsk to attend the funeral of a friend. The NTV national TV channel published footage of Dmitriev at the police station and claimed that he had been attempting to flee the country.[62] To the former charge of child pornography was now added that of "sexual acts of a forcible nature" (Article 132, part 4).[63][64]

On 20 September 2018, the Supreme Court of Karelia turned down an appeal from Dmitriev's lawyer Victor Anufriev to change the measure of restraint on his client from custody at Detention Centre No 1 to home arrest. The first hearing of the new trial was scheduled to take place on that day, but was postponed until 27 September because the accused and his lawyer had not yet finished re-reading the case materials for the old charges.[65] On 27 September the hearing was again postponed for the same reason, until 17 October.[66]

Verdict, sentence and appeals[]

On 22 July 2020, Dmitriev was acquitted of producing pornography and the illegal possession of weapons, but found guilty of sexual assault against his adopted daughter. After the trial ended the evidence for this charge was finally made public.[11] Judge Merkov sentenced him to three years and six months of imprisonment, little more than a quarter of the sentence recommended in the Criminal Code for such an offence.

If the protest against this sentence by the prosecution is not upheld, Dmitriev will be freed in mid-November 2020. Since his first arrest in December 2016, he has already served most of this term of imprisonment, under investigation or awaiting and during his two trials, in detention centre No 1 in Petrozavodsk.[67] At the end of the trial in July 2020, the prosecution asked for him to serve a 15-year sentence in a strict regime penal colony.

The defence has appealed against the conviction, demanding that Yury Dmitriev be cleared of all charges; a lawyer representing his adopted daughter and her grandmother also appealed against the verdict.[68]

Publications[]

Author and editor[]

- 1999 - Sandarmokh, a Place of Execution (in Russian), 350 pp. Bars Publishers: Petrozavodsk.[69]

- 2000 - The Forest, Red with Spilled Blood (Bor, krasnoj ot prolitoj krovi), 214 pp. Petrozavodsk.[70]

- 2002 - (with Ivan Chukhin) The Karelian Lists of Remembrance: Murdered Karelia, part 2, The Great Terror (in Russian), 1,088 pp. Petrozavodsk. (Also available online as «Поминальные списки Карелии, 1937–1938: Уничтоженная Карелия, часть 2. Большой террор».) There are over 14,000 names in the Lists.

- 2003 - The White Sea-Baltic Canal, from plan to implementation: A collection of documents, 250 pp. (in Russian), Petrozavodsk.[71]

- 2017 - launch in CD form of two unpublished books by Dmitriev in Petrozavodsk on 24 May.[72]

- 2019 - Sandarmokh, a Place of Remembrance (in Russian), 520 pp.

- 2020 - "Last Words", Yury Dmitriev's address to the court, 8 July 2020.[73]

Interviews[]

- 2008 - "We must never forget", Karelia weekly, No 122, 30 October (in Russian).

- 2009 - "Yury Alexeyevich Dmitriev", interviewed by Tomas Kizny: The commemorative museum of the NKVD investigative prison, Tomsk (Siberia), (in Russian).

- 2015 - "My path to Golgotha: An interview with Yury Dmitriev", Memorial website (Dmitriev Affair website).

- 2016 - "The dictatorship of fear and lies is returning", Petrozavodsk Speaking, 27 January (in Russian).

- 2018 - "A first interview after release", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 28 January (Dmitriev Affair website).

- 2018 - "Anyone can find themselves in prison - it doesn't take much courage", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 1 February (Open Democracy-Russia).

- 2018 - "The wind groans or rustles: remember me, and me, and me", Sergey Lebedev talks to Yury Dmitriev, Colta.ru, 2 February (in Russian).

Articles about Dmitriev[]

- "Yury Dmitriev, the man who found the Solovki execution site in the groves of Sandarmokh", The Solovki Encyclopaedia (in Russian).

- Anna Yarovaya, "The Dmitriev Affair", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 10 March 2017. (The Russian Reader website)

- Shura Burtin, "The case of Khottabych: The price for attempting to dig up the past", Russian Reporter, 30 May 2017

- John Crowfoot, "Who is Yury Dmitriev?" Rights in Russia, 19 June 2017.

- Rights in Russia website. Nine articles since March 2017 about the Dmitriev case.[74]

- Andrew Osborn, "Hunter of Stalin's mass graves on trial: friends say he's been framed", Reuters, 13 July 2017.

- Sabra Ayres, "An outspoken researcher of Stalin's crimes fights for his own fate and freedom in Russia", Los Angeles Times, 24 July 2017.

- Alec Luhn, "Gulag grave hunter unearths uncomfortable truths in Russia", The Guardian (London), 3 August 2017.

- "Detailed information about the case of Yury Dmitriev" The coalition of human-rights activists, 27 December 2017 (in Russian).

References[]

- ^ Their Names Returned: Russia's Books of Remembrance website (Возвращенные имена.Книги памяти России), Search: "Sandarmokh", "Kniga pamyati Karelii", 4,974 names (accessed 7 August 2017).

- ^ Alexander Daniel, "He roused the Dragon", Rights in Russia, Weekly Update, No. 23 (256) 12 June 2017. Russian source: Zoya Svetova, "The Dmitriev Case and the Dragon of the Great Terror", Open Russia.

- ^ Yekaterina Fomina, "'Papa said he'd sort everything out': Karelian historian Yu. Dmitriev is accused of making pornography using his own daughter", Novaya gazeta, 21 December 2016, (in Russian).

- ^ "The Charges", Dmitriev Affair website, updated 16 February 2018.

- ^ Ayres, Sabra (24 July 2017). "An outspoken researcher of Stalin's crimes fights for his own fate and freedom in Russia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ "Photos not pornographic, say new experts", Chernika,26 December 2017.

- ^ "Psychiatric examination completed", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Next hearing, 27 February 2018", Russian supporters' Facebook page.

- ^ "Prosecutor demands 9-year sentence", Dmitriev Affair website, 20 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "City prosecutor to appeal against Dmitriev acquittal", Petrozavodsk Speaking, 13 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What we've uncovered", Dmitriev Affair website, 24 July 2020.

- ^ “The dictatorship of fear and lies is returning”, Petrozavodsk Speaking, 27 January 2016.

- ^ Sergei Lebedev, Interview with Dmitriev, Colta.ru, 2 February 2018 (in Russian).

- ^ "The dictatorship of fear and lies is returning", Petrozavodsk Speaking, 27 January 2016 (in Russian).

- ^ See Meduza daily news brief, 1 June 2017 (in Russian).

- ^ Irina Galkova, "My path to Golgotha: An interview with Yury Dmitriev", Memorial website, 1 May 2017.

- ^ Anna Yarovaya, "The Dmitriev Affair", 7 x 7 website, 1 March 2017.

- ^ Shura Burtin, "The case of Khottabych", Russian Reporter weekly, 30 May 2017.

- ^ Irina Galkova, "My path to Golgotha: An interview with Yury Dmitriev", Dmitriev Affair website.

- ^ "Ivan Chukhin", Virtual Museum of the Gulag (in Russian).

- ^ Anna Yarovaya "The Dmitriev Affair", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 10 March 2017.

- ^ "My path to Golgotha: An interview with Yury Dmitriev", Memorial website.

- ^ Anna Yarovaya, "The Dmitriev Affair", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 1 March 2017.

- ^ "The Solovki transports, 1937-1938", Their Names Restored website (in Russian).

- ^ Anna Yarovaya, "Badgers' Hill: Nine hectares of mass graves", 7x7 horizontal Russia website, 29 September 2017 (in Russian).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A note about the case of Yury Dmitriev" The coalition of human-rights activists, 27 December 2017 (in Russian).

- ^ David Satter, It was a long time ago, and anyway it never happened: Russia and the Communist Past, Yale University Press, 2011, p. 194.

- ^ The Golden Pen of Russia, a national literary prize, "Prize-winners, 2005 onwards" (in Russian). Dmitriev was among the first 23 authors to receive the new prize.

- ^ Polish Consultate-General, St Petersburg, "Days of Remembrance for the Victims of Political Repression", 20 August 2015 (in Russian and Polish).

- ^ Georgy Borodyansky, "An Award for the Truth", GDF Weekly Digest, 5 February 2018 (in Russian).

- ^ "Gulag historian punished for digging up Russia's past, rights groups say". 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Karelian Supreme Court toughens sentence against Yury Dmitriyev to 13 years".

- ^ "What is Memorial hiding", Rossiya-24, Evening news, 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Yury Dmitriev should be acquitted", Rights in Russia Weekly Update, No 23 (256) 12 June 2017, Zoya Svetova interviews Dmitriev defence attorney Victor Anufriev.

- ^ Alexander Gnetnev and Yelizaveta Maetnaya, "People trust him", Radio Svoboda, 1 June 2017 (in Russian).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The new experts in the Dmitriev case come from a private firm without office or employees (Novaya gazeta) - Rights in Russia". www.rightsinrussia.info. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ "Yury Dmitriev's supporters", Rights in Russia Weekly Update, No (258), 21 June 2017.

- ^ Change.org - «Мы требуем восстановления законности в деле Дмитриева» (We demand that the laws be respected in the case of Yury Dmitriev!)

- ^ "The head of Memorial in Karelia has gone on trial, accused of preparing child pornography", Meduza daily news brief, 1 June 2017, in Russian.

- ^ Andrew Osborn, "Hunter of Stalin's mass graves on trial: friends say he's been framed", Reuters, World News, 13 July 2017.

- ^ Anna Yarovaya, "Four more experts testify in defence of Dmitriev", 7x7: Horizontal Russia news website, 11 July 2017.

- ^ Anna Yarovaya, "New analysis of photos not ready - next hearing 29 November 2017", 7x7-Horizontal Russia, 25 October 2017 in The Dmitriev Affair website.

- ^ "Photos not pornographic, say new experts", Chernika, 26 December 2017.

- ^ Davidoff, Victor (13 October 2013). "Soviet Psychiatry Returns". Moscow Times. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Dmitriev to be released on 28 January 2018", 7x7 - Horizontal Russia, 27 December 2017.

- ^ Gleb Yarovoi, Yelena Bayakina, "Dmitriev transferred to Moscow for psychiatric assessment", 7x7 - Horizontal Russia, 28 December 2017.

- ^ The Dmitriev Affair (Дело Дмитриева) Facebook page

- ^ "Yuri Dmitriev: I lived in the same cell as the convicts of 1937-1938". The Independent Barents Observer. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Историк Юрий Дмитриев на свободе. Новая газета - Novayagazeta.ru (in Russian). 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (5 April 2018). "Russian Historian Who Exposed Soviet Crimes Is Cleared in Pornography Case". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (5 April 2018). "Russian historian who exposed Stalin's crimes cleared of child pornography". Reuters. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "One in 446: why Russian courts are issuing even fewer acquittals", RBC online, 25 April 2018 (in Russian). In 2017 acquittals fell to only 0,2% of all cases.

- ^ See data and sources, for example, in Partial Justice: An enquiry into the deaths of journalists in Russia, 1993-2009.

- ^ "Суд рассмотрит апелляционные жалобы по делу Дмитриева в июне". stolicaonego.ru. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ "The Supreme Court of Karelia has overturned the acquittal of Yury Dmitriev", Meduza website, 14 June 2018.

- ^ Maria Eismont, "The Dmitriev case is the most important thing happening in Russia right now", The Russian Reader website, 8 July 2017, Russian original Vedomosti newspaper.

- ^ Nikolai Podosogorsky, "Alexander Gelman has recorded a video address in defence of the historian Yury Dmtriev", Live Journal, 25 July 2017 Retrieved 9 August 2017 (in Russian).

- ^ "Video clips". The Dmitriev Affair. 2017-10-14. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Alexander Arkhangelsky, "Dmitriev found a lever to reverse the rotation of the globe", 22 June 2017, Dmitriev Affair website (in Russian).

- ^ Natalya Solzhenitsyn, 1 October 2017, Dmitriev Affair website (in Russian).

- ^ Sculptor Georgy Frangulyan, 27 October 2017, Dmitriev Affair website, with English translation.

- ^ Halya Coynash, "Russia brings new fabricated charges against Yury Dmitriev", Human Rights in Ukraine, 28 June 2018.

- ^ "Will we fight?" asked Yury Dmitriev", Dmitriev Affair website, 29 June 2018.

- ^ "Lawyer: Russian Activist Arrested After Acquittal Reversed", New York Times, 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Dmitriev to remain in custody", Dmitriev Affair website, 22 September 2018.

- ^ "Trial delayed for a month", Dmitriev Affair website, 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Gulag historian Yury Dmitriev jailed on sexual assault charges, set to go free in November", RTVi, 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Appeals lodged by all parties", Dmitriev Affair website, 3 August 2020.

- ^ Book in pdf format.

- ^ Volume about Krasny Bor killing field, edited by Dmitriev, 2017 reprint.

- ^ Book in pdf format.

- ^ "New books by Yury Dmitriev", Rights in Russia, Weekly Update No. 22 (255), 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Who is a patriot?" Medusa, 21 July 2020.

- ^ Mentions of Yury Dmitriev on Rights in Russia.

External links[]

![]() Media related to Yury Alexeyevich Dmitriev at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yury Alexeyevich Dmitriev at Wikimedia Commons

English[]

- The Dmitriev Affair website

- "Free Yury Dmitriev!" open letter

- Free Yury Dmitriev! — Supporters' group on Facebook

- Change.org petition — "Public Appeal in Defense of Gulag researcher Yury Dmitriev"

Russian[]

- «Дело Дмитриева» (The Dmitriev Case) — website in support of Dmitriev

- «Дело Дмитриева» (The Dmitriev Case) — Supporters' group on Facebook

- 7x7 Horizontal Russia: The Dmitriev Affair

- Change.org petition — «Мы требуем восстановления законности в деле Дмитриева» (We demand that the laws be respected in the case of Yury Dmitriev!)

- 1956 births

- Living people

- People from Petrozavodsk

- Gulag

- Russian human rights activists

- Memorial (society)

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Recipients of the Gold Cross of Merit (Poland)

- Political prisoners according to Memorial