Zungeni Mountain skirmish

| Zungeni Mountain skirmish | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Zulu War | |||||||

Death of Lieutenant Frith, as depicted by Melton Prior in the Illustrated London News of 2 August 1879 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Zulu Kingdom | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 300 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| One officer killed, at least two men wounded | At least 25 warriors killed | ||||||

class=notpageimage| Approximate location in present-day South Africa | |||||||

The Zungeni Mountain skirmish took place on 5 June 1879 between British and Zulu forces during the Second invasion of Zululand. British irregular horse commanded by Colonel Redvers Buller discovered a force of 300 Zulu levies at a settlement near the Zungeni Mountain. The horsemen charged and scattered the Zulu before burning the settlement. Buller's men withdrew after coming under fire from the Zulu who also threatened to surround them.

A force of regular British cavalry commanded by Major-General Frederick Marshall arrived on the scene and were eager to see action. A squadron of the 17th (The Duke of Cambridge's Own) Lancers, led by Colonel Drury Drury-Lowe, charged the Zulu. They cleared the open ground but were not able to press into an area of long grass and bushes from which the Zulu were firing upon the British. The lancers withdrew after their regimental adjutant, Lieutenant Frederick John Cokayne Frith, was killed by a sniper and the Zulu threatened to outflank them. The British then withdrew to their camp of the previous night. Aside from Frith the British casualties included two irregulars wounded; two months after the battle the remains of 25 Zulu were discovered on the battlefield. After the skirmish the British paused to fortify their camp before proceeding into Zululand, decisively defeating the Zulu in the 4 July Battle of Ulundi.

Background[]

The British, under Lord Chelmsford, invaded Zululand in January 1879. The first invasion ended following the defeat of the British Centre Column at the 22 January Battle of Isandlwana and the British right and left columns remained at positions they had reached at Eshowe and Kambula respectively.[2] Chelmsford sent to Britain for fresh reinforcements, which included a cavalry brigade formed by the 1st King's Dragoon Guards and the 17th (The Duke of Cambridge's Own) Lancers under the command of Major-General Frederick Marshall.[3]

Chelmsford relieved the Siege of Eshowe on 3 April and withdrew the right column back to the Colony of Natal. He reorganised his forces into two main thrusts, the reinforced centre column, including the cavalry brigade, became the Second Division that would advance on the Zulu capital Ulundi.[4] The left column, which contained a high proportion of irregular horse, which fought as mounted infantry, was re-designated as a flying column under Colonel Evelyn Wood.[5] Wood's column was to operate in conjunction with the Second Division, supporting its advance on Ulundi.[4][5] The reinforced right column was re-designated the First Division and was tasked with a slow advance along the east coast.[4]

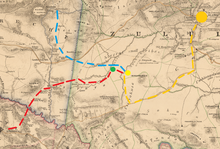

By the end of May the Second Division, commanded by Major-General Edward Newdigate, had moved forwards from Dundee and was assembled on the banks of the Ncome River at Koppie Alleen, ready to commence the invasion. Chelmsford joined the division on 31 May and commenced the advance into Zululand, simultaneously with Wood further north.[6] On 1 June Napoléon, Prince Imperial of France, who had marched with the Second Division, was killed during a skirmish.[7] The Second Division and Wood's flying column met on 3 June at a point on the .[5][8] The following day a patrol of from the flying column fought a minor skirmish at a cluster of four Zulu homesteads, belonging to Sihayo kaXongo, around 400 yards (370 m) west of Zungeni Mountain. They recovered three wagons and an ammunition cart that had been looted from the British at Isandlwana.[9]

Skirmish[]

Irregular horse[]

On the morning of 5 June mounted irregulars from Wood's flying column encountered a force of around 300 Zulu at eZulaneni, a collection of four large homesteads between the Zungeni Mountain (which was known to the British as Ezunganyan Hill) and the Ntinini stream.[10][11] The horsemen were commanded by Colonel Redvers Buller and included a squadron of Baker's Horse, a squadron of the Frontier Light Horse, No. 3 Troop (Bettington's Horse) of the , a troop of the Natal Light Horse and a number of , totalling around 300 men.[12]

Buller's men charged, scattering the Zulu and burning the homesteads.[10] The Zulu counterattacked around the British flanks, in their classic "horns of the buffalo" formation. The British recognised the risk of being surrounded and withdrew, being fired upon by Zulu skirmishers in cover on their flanks.[6][10] Two of Buller's men were wounded in this first phase of the skirmish.[11]

Regular cavalry[]

Marshall received news that a sizeable Zulu force had been spotted and left the Second Division's camp with around 500 men of his brigade at 4.30 am on the morning of 5 June.[11][13] He then followed the sound of gunfire to Zungeni where he found Buller's men retiring from combat.[11][6] The men, recently arrived in Africa, were eager to see action.[10] A squadron each from the King's Dragoon Guards and the 17th Lancers were committed to the action.[14][15]

Three troops of the 17th Lancers were led forwards by their colonel, Drury Drury-Lowe.[11][16] Drury-Lowe ordered some of his men to dismount and return the fire of the Zulus who were sniping from concealment in long grass and bushes.[11] He led the remainder on a charge in line formation. The cavalry swept past the Zulus several times but were unable to engage them in close combat owing to the difficult terrain.[6] The Zulus held their ground and shot at the passing riders, killing the 17th Lancer's adjutant Lieutenant Frederick John Cokayne Frith.[6]

Private Miles Gissop in a November 1899 talk described being with A and E troops clearing an open field of Zulu at lancepoint but being unable to pursue them into the difficult terrain. He noted that Frith was shot in the heart and killed from a range of 300 yards (270 m).[17] The Illustrated London News's correspondent Melton Prior witnessed Frith's death and noted he was killed whilst riding between Colonel Drury-Lowe and Mr Francis, correspondent of The Times.[18] Gissop recalled that Frith had been shot immediately after Drury-Lowe had reassured his lancers: "you are all right men. You are all right, they are all passing over your heads". Gissop noted that Frith stated "Oh I'm shot" before falling dead from his horse.[17] It was later determined that the bullet that killed Frith had been made in Britain and was fired from a Martini–Henry rifle, both having been captured by the Zulu during earlier engagements.[6]

Frith's death and the movement of the Zulus to outflank the lancers led to the end of the action.[6][10] Marshall moved a troop of the King's Dragoon Guards forwards to cover the lancers as they withdrew and Buller's irregulars also provided covering fire.[10] Gissop noted that after the withdrawal some Zulu emerged from the bushes to count the British dead, though there was only Frith.[17]

Frith's body was carried back to the British camp at the Nondweni, some 5 miles (8.0 km) back on the route of march, where he was buried in a mealie field that evening.[17][6] A British firewood gathering party found 25 Zulu dead from the action in the bushes and grass on the battlefield on 3 August.[11][10]

Aftermath[]

After the skirmish the British returned to their own columns and the Nondweni camp.[11] During the day of the action Chelmsford was interviewing three peace envoys from the Zulu king Cetshwayo; these were sent away that evening with conditions that would be largely unacceptable to Cetshwayo.[11] The British established the camp as a fortified base, known as Fort Newdigate, to support the advance further into Zululand.[6] A further raid on Zungeni was mounted on 8 June by a force of lancers, dragoons and two 7-pounder artillery pieces. This drove off a force of Zulus and burnt many homesteads.[16]

The discovery of a group of Zulu at Zungeni had led to fears that a Zulu army was nearby. Amongst other things this led to the postponement of the court-martial of Lieutenant Jahleel Brenton Carey for failing in his duty as commander during the death of the Prince Imperial.[19] The skirmish proved that these were not royal warriors but only local levies. Carey's court-martial proceeded on 12 June and he was found guilty of "misbehaviour before the enemy".[20]

The 2nd Division and Wood's flying column continued their march into Zululand, patrolling regularly to drive off Zulu forces and establishing several more fortified camps. The Zulu were finally defeated at the 4 July Battle of Ulundi. Afterwards some of the horsemen from the force were released from duty and returned to Natal, others were kept on for the pacification of Zululand.[5][1] Prior had made a sketch of the moment of Frith's death and an engraving of this was published on the front page of the 2 August 1879 edition of the Illustrated London News.[21]

References[]

- ^ a b Smith 2014, p. 194.

- ^ Knight & Castle 2003, p. 62.

- ^ Laband 2009, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Knight & Castle 2003, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d Laband 2009, p. 309.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Greaves 2005, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Knight & Castle 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 189.

- ^ Laband 2009, p. 313.

- ^ a b c d e f g Laband 2009, pp. 323–324.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rothwell 1989, p. 96.

- ^ Laband 2009, pp. 10, 100, 175, 176, 254, 323–324.

- ^ Laband 2009, pp. 150, 323–324.

- ^ Laband 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Laband 2009, p. 68.

- ^ a b Smith 2014, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d Clammer 1980, pp. 87–88.

- ^ "Zulu War Illustrations". Illustrated London News. No. 2094. 2 August 1879. p. 109.

- ^ David 2004, pp. 331.

- ^ David 2004, pp. 331, 333.

- ^ "The Zulu War Death of Lieutenant Frith in Skirmish at Erzungayan Hill". Illustrated London News. No. 2094. 2 August 1879. p. 97.

Bibliography[]

- Clammer, David (1980). "The Recollections of Miles Gissop: With the 17th Lancers in Zululand". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 58 (234): 78–92. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44223296.

- David, Saul (2004). Zulu: The Heroism and Tragedy of the Zulu War of 1879. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-91474-6.

- Greaves, Adrian (2005). Crossing the Buffalo: The Zulu War of 1879. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-3043-6725-2.

- Knight, Ian; Castle, Ian (2003). Zulu War 1879: Twilight of a Warrior Nation. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-165-3.

- Laband, John (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Zulu Wars. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6300-2.

- Rothwell, Captain J.S. (1989). Narrative of the Field Operations Connected with the Zulu War of 1879. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-041-3. OL 8980321M – via Quartermaster General's Department, Intelligence Branch, War Office.

- Smith, Keith (2014). Dead Was Everything: Studies in the Anglo-Zulu War. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-3723-2.

- Battles of the Anglo-Zulu War

- 1879 in the Zulu Kingdom

- History of KwaZulu-Natal

- June 1879 events