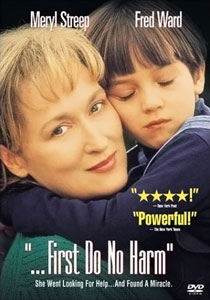

...First Do No Harm

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

| ...First Do No Harm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Written by | Ann Beckett |

| Directed by | Jim Abrahams |

| Starring | Meryl Streep Fred Ward Seth Adkins Allison Janney Margo Martindale Leo Burmester Tom Butler |

| Music by | Hummie Mann |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Executive producers | Howard Braunstein Michael Jaffe Meryl Streep |

| Producer | Jim Abrahams |

| Cinematography | Pierre Letarte |

| Editor | Terry Stokes |

| Running time | 94 minutes |

| Production companies | Pebblehut Productions Jaffe/Braunstein Films |

| Distributor | FremantleMedia |

| Release | |

| Original network | ABC |

| Original release | February 16, 1997 |

...First Do No Harm is a 1997 American made-for-television drama film directed by Jim Abrahams about a boy whose severe epilepsy, unresponsive to medications with terrible side effects, is controlled by the ketogenic diet. Aspects of the story mirror Abrahams' own experience with his son Charlie.

Plot[]

The film tells a story in the life of a Midwestern family, the Reimullers. Lori (played by Meryl Streep) is the mother of three children, and the wife of Dave (Fred Ward), a truck driver. The family are presented as happy, normal and comfortable financially: they have just bought a horse and are planning a holiday to Hawaii. Then the youngest son, Robbie (Seth Adkins), has a sudden unexplained fall at school. A short while later, he has another unprovoked fall while playing with his brother, and is seen having a convulsive seizure. Robbie is taken to the hospital where a number of procedures are performed: a CT scan, a lumbar puncture, an electroencephalogram (EEG) and blood tests. No cause is found but the two falls are regarded as epileptic seizures and the child is diagnosed with epilepsy.

Robbie is started on phenobarbital, an old anticonvulsant drug with well-known side effects including cognitive impairment and behavior problems. The latter cause the child to run berserk through the house, leading to injury. Lori urgently phones the physician to request a change of medication. It is changed to phenytoin (Dilantin) but the dose of phenobarbital must be tapered slowly, causing frustration. Later, the drug carbamazepine (Tegretol) is added.

Meanwhile, the Reimullers discover that their health insurance is invalid and their treatment is transferred from private to county hospital. In an attempt to pay the medical bills, Dave takes on more dangerous truck loads and works long hours. Family tensions reach a head when the children realize the holiday is not going to happen and a foreclosure notice is posted on the house.

Robbie's epilepsy gets worse, and he develops a serious rash known as Stevens–Johnson syndrome as a side effect of the medication. He is admitted to hospital where his padded cot is designed to prevent him escaping. The parents fear he may become a "vegetable" and are losing hope. At one point, Robbie goes into status epilepticus (a continuous convulsive seizure that must be stopped as a medical emergency). Increasing doses of diazepam (Valium) are given intravenously to no effect. Eventually, paraldehyde is given rectally. This drug is described as having possibly fatal side effects and is seen dramatically melting a plastic cup (a glass syringe is required).

The neurologist in charge of Robbie's care, Dr. Melanie Abbasac (Allison Janney), has poor bedside manner and paints a bleak picture. Abbasac wants the Reimullers to consider surgery and start the necessary investigative procedures to see if this is an option. These involve removing the top of the skull and inserting electrodes on the surface of the brain to achieve a more accurate location of any seizure focus than normal scalp EEG electrodes. The Reimullers see surgery as a dangerous last resort and want to know if anything else can be done.

Lori begins to research epilepsy at the library. After many hours, she comes across the ketogenic diet in a well-regarded textbook on epilepsy. However, their doctor dismisses the diet as having only anecdotal evidence of its effectiveness. After initially refusing to consider the diet, she appears to relent but sets impossible hurdles in the way: the Reimullers must find a way to transport their son to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland with continual medical support—something they cannot afford.

That evening, Lori attempts to abduct her son from the hospital and, despite the risk, fly with him to an appointment she has made with a doctor at Johns Hopkins. However, she is stopped by hospital security at the exit to the hospital. A sympathetic nurse warns Lori that she could lose custody of her son if a court decides she is putting her son's health at risk.

Dave makes contact with an old family friend who once practiced as a physician and is still licensed. This doctor and the sympathetic nurse agree to accompany Lori and Robbie on the trip to Baltimore. During the flight, Robbie has a prolonged convulsive seizure, which causes some concern to the pilot and crew.

When they arrive at Johns Hopkins, it becomes apparent that Lori has deceived her friends as her appointment (for the previous week) was not rescheduled and there are no places on the ketogenic diet program. After much pleading, Dr. Freeman agrees to take Robbie on as an outpatient. Lori and Robbie stay at a convent in Baltimore.

The diet is briefly explained by Millicent Kelly (played by herself) a dietitian who has helped run the ketogenic diet program since the 1940s. Robbie's seizures begin to improve during the initial fast that is used to kick-start the diet. Despite the very high-fat nature of the diet, Robbie accepts the food and rapidly improves. His seizures are eliminated and his mental faculties are restored. The film ends with Robbie riding the family horse at a parade through town. Closing credits claim Robbie continued the diet for a couple of years and has remained seizure- and drug-free ever since.

Background[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2020) |

The director and producer, Jim Abrahams, was inspired to make the film as a result of his own experiences with his son Charlie. Charlie developed a very serious seizure condition that proved intractable despite several medications and surgery. His cognitive decline was described by Abrahams as "a fate worse than death". He came across the diet in a book on childhood epilepsy by John Freeman, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Charlie was started on the diet and rapidly became seizure-free. In addition, medications were tapered and his mental development restored. Abrahams was outraged that nobody had informed him of the diet. He created the Charlie Foundation to promote the diet and funded research studies to demonstrate its effectiveness.

Although the film plot has parallels with the Abrahams' story, the character of Robbie is a composite one and the family circumstances are fictional. Several minor characters in the film are played by people who have been on the ketogenic diet and had their epilepsy "cured" as a result. The dietitian Millicent Kelly plays herself. Charlie Abrahams appears as a young boy playing with Robbie in the hospital, whose mother quickly removes him when she discovers Robbie has epilepsy—as though it were an infectious disease.

Commenting on the film, John Freeman said "The movie was based on a true story and we see this story often, but not everyone is cured by the diet and not everyone goes home to ride in a parade." He later noted that the film had "fueled a grass-roots effort for more research on the diet."

The film was first broadcast on 16 February 1997. It was subsequently released on DVD.

Meryl Streep's performance was nominated for an Emmy, a Golden Globe and in the Satellite Awards in the category Best Actress in a TV Film. Writer Ann Beckett was nominated for the Humanitas Prize (90 minute category). Seth Adkins won a Young Artist Award for his performance as Robbie.

See also[]

- Never events

- Primum non nocere

References[]

- Jim Abrahams (2003). "Things I Wish They Had Told Us: A Parent's Perspective on Childhood Epilepsy". The Charlie Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- John Freeman (2003). "Talk with John Freeman: Tending the Flame". Brainwaves. 16 (2). Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- Denise Mann (2000-07-06). "Movie First Do No Harm Boosts Popularity of Diet for Epileptic Children". WebMD Medical News.

- Venita Jay (April 1997). "...first do no harm". Epilepsy Ontario 'Sharing' News. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- Kathleen Fackelmann (1999-01-12). "Recognizing a 'miracle' The high-fat ketogenic diet can ease seizures in epileptic children". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2009-11-13. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- Freeman JM, Kossoff EH, Hartman AL (March 2007). "The ketogenic diet: one decade later". Pediatrics. 119 (3): 535–43. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2447. PMID 17332207. S2CID 26629499.

External links[]

- 1997 television films

- 1997 films

- 1997 drama films

- American drama films

- American films

- American television films

- Drama films based on actual events

- Drama television films

- English-language films

- Films about emotions

- Films about families

- Films directed by Jim Abrahams

- Films scored by Hummie Mann

- Johns Hopkins Hospital in fiction

- Low-carbohydrate diets

- Medical-themed films