1808 mystery eruption

The 1808 mystery eruption was a large volcanic eruption conjectured to have taken place in late 1808, possibly in the southwest Pacific. A VEI-6 eruption, comparable to the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, is suspected of having contributed to a period of global cooling that lasted for years,[2][3] analogous to how the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora (VEI-7) led to the Year Without a Summer in 1816.

Background[]

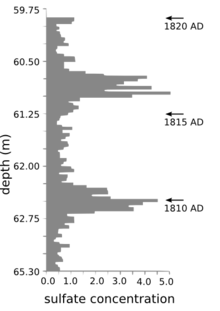

Before the 1990s, the deterioration of the weather in the early 1810s was considered by climatologists as normal for the Little Ice Age. A study of Greenland and Antarctic ice cores in the 1990s found markers that implied that a massive volcanic eruption had occurred in early 1809. The problem facing climatologists and volcanologists was that there were no recorded eruptions of the order of significance needed in this period.[4] Further research and bristlecone pine tree ring data pointed to the eruption being in 1808.[5]

Location and date[]

Adding to the mystery was the expectation that any eruptions of that magnitude should have been noticed at the time. Records from the time throughout the world were checked but nothing appeared viable until the summer of 2014, when PhD student Alvaro Guevara-Murua and Dr Caroline Williams of the University of Bristol discovered an account of atmospheric events consistent with such an event by Colombian scientist Francisco José de Caldas.

Caldas served as Director of the Astronomical Observatory of Bogotá between 1805 and 1810 and in 1809 reported a transparent cloud that obstructs the sun's brilliance at Bogotá. It had first been observed by him on 11 December 1808 and was visible across Colombia.[3] The cloud might have been a "dry fog", which is a sulfuric acid (H2SO4) aerosol.[3] He also reported that the weather had been unusually cold, with frosts.

To the south, in Peru, similar observations were made by physician Hipólito Unanue of Lima.[3] These reports led those involved to suggest that the window of the eruption was within 7 days of 4 December 1808.[3] Caldas' and Unanue's accounts indicated the existence of a stratospheric aerosol veil spanning at least 2600 km into both northern and southern hemispheres. The only likely source for this would be a tropical volcano, most likely located in the southern hemisphere but not likely further than 20 degrees south latitude.[3]

An area in the tropics to the west of Colombia and Peru with candidate volcanoes and with little reporting at that time is the south-western Pacific Ocean between Indonesia and Tonga. This area had no European settlements at the time. Apart from the occasional sighting by European explorers, most of the reporting on volcanic activity, such as that in the Rabaul area, which has had VEI 6 eruptions, went back only to the mid-19th century.[6] There were oral histories of eruptions among the indigenous populations in these areas but these could not be dated with any degree of certainty.[7]

Known significant eruptions in 1808[]

In 1808 there were major eruptions in Urzelina, Azores, in May (1st to 4th), and in Taal Volcano, Philippines, in March.[8] Neither of these occurred within the correct time period for the visual observations.

It is known that the Chilean Putana volcano also had a major eruption around this time with an approximate date of 1810 (with a 10-year margin of error), but is located 22 degrees south.[9]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Dai, Jihong; Mosley-Thompson, Ellen; Thompson, Lonnie G. (1991). "Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 96 (D9): 17, 361–17, 366. Bibcode:1991JGR....9617361D. doi:10.1029/91jd01634.

- ^ "Mysterious Volcanic Eruption of 1808 Described". Science Daily. University of Bristol. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Guevara-Murua, A.; Williams, C. A.; Hendy, E.J.; Rust, A.C.; Cashman, K.V. (2014). "Observations of a stratospheric aerosol veil from a tropical volcanic eruption in December 1808: is this the Unknown ∼ 1809 eruption?" (PDF). Climate of the Past. 10 (5): 1707–1722. Bibcode:2014CliPa..10.1707G. doi:10.5194/cp-10-1707-2014.

- ^ Dai, Jihong; Mosley-Thompson, Ellen; Thompson, Lonnie G. (1991). "Ice Core Evidence for an Explosive Tropical Volcanic Eruption Six Years Preceding Tambora". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 96 (D9): 17, 361–17, 366. Bibcode:1991JGR....9617361D. doi:10.1029/91jd01634.

- ^ Salzer, Matthew W.; Hughes, Malcolm K. (January 2007). "Bristlecone Pine Tree Rings and Volcanic Eruptions Over the Last 5000 yr". Quaternary Research. 67 (1): 57–68. Bibcode:2007QuRes..67...57S. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2006.07.004. S2CID 14654597.

- ^ 2. Volcano Sightings by European Navigators: 1528–1870, Fire Mountains of the Islands, R Wally Johnson, ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia, ISBN 978-1-922144-22-5 (pbk.) 9781922144232 (eBook)

- ^ http://www.volcanolive.com/savo.html Savo - Toghavitu Eruption. Retrieved 24 November 2015

- ^ Knittel, Ulrich (1999). "History of Taal's Activity to 1911 as Described by Fr. Saderra Maso". Institut für Mineralogie und Lagerstättenlehre, RWTH Aachen University. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ http://www.volcanocafe.org/1809-the-missing-volcano/ retrieved 24 April 2018

External links[]

- 19th-century volcanic events

- 1808

- Events that forced the climate

- Plinian eruptions

- Unexplained phenomena

- VEI-6 eruptions