1937 Brazilian coup d'état

| 1937 Brazilian coup d'état | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Vargas Era | |

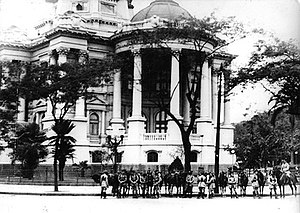

Troops guard the Palácio Monroe, then-seat of the Brazilian Senate, on 10 November 1937 | |

| Date | 10 November 1937 |

| Location | |

| Caused by |

|

| Goals |

|

| Methods |

|

| Resulted in | Military/government success:

|

| Casualties | |

| Arrested | Several |

A military coup, known as the 1937 coup (Portuguese: Golpe de 1937) or the Estado Nôvo coup (Portuguese: Golpe do Estado Novo),[1] was initiated on 10 November 1937 in Brazil by President Getúlio Vargas with the support of the Brazilian Armed Forces. Vargas had risen to power in a revolution which had ended a decades-old oligarchy, already with the backing of the military. For four years he ruled as provisional president until elections were held for a National Constituent Assembly. Under a new 1934 constitution, Vargas became the constitutional president of Brazil. Following a 1935 communist uprising, speculation was already rising about a potential self-coup, however. Candidates for the 1938 Brazilian presidential elections were appearing as early as late 1936. Vargas could not seek reelection, but he and his allies were not willing to abandon power. Political repression, which was magnified after the communist revolt, was now being loosened. However, a strong sentiment for a dictatorial government amongst the military, as well as further federal intervention in state governments, paved the way for a coup to take place.

With preparation beginning officially on 18 September 1937, senior military officers used the , a fradulent document, to provoke the National Congress of Brazil into declaring a state of war. Rio Grande do Sul Governor , who was opposed to President Vargas, left for exile in mid-October 1937 with little other options. A new constitution was also being drafted by . By November, the President held almost all power in the country and nothing was standing in the way of the intricate plan from taking place. On the morning of 10 November 1937, the military surrounded the National Congress. The cabinet expressed approval for the new corporatist constitution, and a radio address by Vargas proclaimed the new regime, the Estado Nôvo.

In the aftermath of the coup, a semi-fascist, authoritarian state was propped up in Brazil based on European fascist countries. Individual liberties and rights were stripped away, Vargas's term of office was extended by six years, and the power of the states was gone. Foreign reaction was mostly negative. South American countries were hostile to the coup with the exception of Argentine military circles. Germany and Italy rejoiced with some exceptions with the former. In the United States and United Kingdom, reaction to the coup was overall unfavorable.

Background[]

Brazil in the early 1930s[]

Right: Standing is Góis Monteiro who would later be one of the orchestrators of the 1937 coup. Right of Monteiro is Vargas, 8 November 1930.

The First Brazilian Republic (1889–1930) came to an end in 1930 at the hands of the Revolution of 1930. The oligarchy of "coffee with milk", which had dominated Brazilian politics since the 1890s and concentrated power in the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, was now being undermined by an economic crisis.[2] The coffee and milk oligarchy collapsed in it of itself when then-President and paulista[a] Washington Luís violated the agreement by nominating paulista Júlio Prestes to succeed him instead of acting within the lines of the agreement and nominating a person from Minas Gerais.[3] In response, Minas Gerais formed the with the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Paraíba to counter the move, nominating Getúlio Vargas for the presidency in the upcoming 1930 Brazilian general election. Prestes's narrow victory in March (along with the unrelated assassination of Vargas's running mate João Pessoa in July) prompted Vargas and supporters to initiate an armed revolution in October of the year and install a new republic within Brazil.[4][5][6]

In the aftermath of the episode, Vargas dissolved Congress and inferior representative bodies, established an emergency regime, replaced almost all state presidents with "intervenors", and assumed all policymaking power.[7][8][9][10] At this point he was already supported by the military and figures such as military politician General .[7] A civil war was briefly instigated for three months from 9 July to 2 October 1932 when the paulistas staged a revolution – the Constitutionalist Revolution. They failed to defeat the federal government, however.[11] Until then Vargas was a provisional president,[12] but he permitted the May 1933 election of a National Constituent Assembly which convened until 1934. In July of that year, they produced a constitution and elected Vargas to a four-year term as constitutional president ending on 3 May 1938, beginning a quasi-democratic period.[13][14][15][16]

Communist insurrection (1935)[]

From 23 November to 27 November 1935, a Brazilian Communist Party–backed attempted military coup was initiated in Rio Grande do Norte. Its capital, Natal, was shortly governed by a junta until it was defeated.[17][18] Likewise, movements in Recife and Rio de Janeiro followed. There, the encounters between troops were especially bloody and several were left dead.[19][17] The aftermath was severe. Historians Boris and Sergio Fausto state, "it opened the way for far-reaching repressive measures and for an escalation of authoritarianism."[19] The PCB[b] in particular and the political left-wing in general were oppressed under the authority of the executive branch and the procurement of the National Congress. For instance, the National Commission for Stopping Communism (or the National Commission for the Repression of Communism) was created in January alongside more government organs, such as the [pt] created in October, to investigate the 1935 uprising, though the TSN ended up becoming a permanent organization until 1945.[20][21] Congress was sieged by police in March ending with the arrest of several pro-National Liberation Alliance, a leftist front, assemblymen, and many communists were imprisoned and exiled.[20][22][23] The 1934 constitution essentially existed only de jure as it was ignored by the states of emergency, police actions, and the anti-communist climate.[24] The importance of the revolt is because, in its aftermath, it saw the first speculation of Vargas initiating a self-coup.[25]

Speculation and influential factors (1935–1937)[]

Through late 1936 to early 1937, presidential candidates began to appear for the January 1938 presidential elections. Armando de Sales Oliveira was supported by the ; José Américo de Almeida was supported by the Vargas government; and Plínio Salgado was supported by the Brazilian Integralist Action (AIB).[26][27] Vargas could not succeed himself unless he waited four years for the next election.[28][better source needed] According to historian Richard Bourne, "Although [Oliveira] was objectively an opposition candidate, he began a decorous kind of campaign, speaking to businessmen rather than the public at large and trying to minimize any offence to the Federal Government."[29] A coalition of governors assembled by selected Almeida from Paraíba as the government candidate in May 1937.[29] In June, Salgado stepped in and promulgated that he was Jesus's injunction to the electorate.[30] However, the President's 1937 New Year's Address, which declared a "free and healthy atmosphere" for elections, was facing roadblocks. Across the world, war threatened Europe. At home, the states found new difficulties, the military wanted intervention, and the far-right was becoming militant.[31]

The Brazilian Integralist Action party was able to make advancements by appealing to the masses. It was a fascist, nationalistic, and church-centered political party that was essentially a hybrid between Catholicism, mysticism, and order and progress. The Integralists were recognizable by their saluting, green shirt uniforms, and parades; the party also received financial support from the German Embassy.[32] Just a few months after the 1937 coup, an attempted putsch led by armed Integralists on the , residence of President Vargas, was nearly successful.[33] Otherwise, they had a strong effect on the military which helped the 1937 coup.

With that, political debates began to emerge, suppressive measures were lifted, and three hundred prisoners were released by an order from the minister of justice.[26][31] When the 1935 uprising broke out, Congress declared a ninety-day state of war in December and extended it five times; Congress now refused to prolong the state of war.[26][34] Vargas and his allies were not ready to abandon power. They trusted none of the candidates, and an observer close to the government went as far as to say Brazil was at risk of following the path of Spain – destroyed by civil war.[26] In the military, there was amounting support for "a strong state, dictatorial solution for Brazil's evils." as Bourne says.[30] Some officers were influenced by the Nazi and fascist states in Europe and others by Integralism, such as Integralist General Newton Cavalcanti.[30][27] Almeida's increasing shift to the left only complicated the situation and the political climate was reverted to the lead-up of the Revolution of 1930.[31]

Through 1937, the federal government interferred in different states to "nip any possible regional difficulties in the bud" as the Faustos put it.[35] Vargas ordered more frequent interventions in the states, including Mato Grosso and Maranhão. The latter had had its pro-Vargas governor impeached by the opposition.[36] Intervenor and governor for Rio Grande do Sul , who had already been against the President,[37] was now being contested by Vargas. The President upped the power of the federal military commander in Rio Grande do Sul, attempted to contest Cunha in the Governor's state assembly, and declared a state of siege via decree in April as part of his attempts to attack the Governor's armed stregnth. The military also joined in the effort and made a plethora of accusations against the Governor.[36][38] Lima Cavalcanti, Pernambuco governor and one who held deteriorating relations with the federal government, was also a target.[39] Rumors surfaced that Vargas was preparing to cancel elections, and the atmosphere was described in mid-September by journalist[40] Maciel Filho:[41]

Getúlio's strength merits a golpe[c] to end this foolishness. The navy is firm and dictatorial-minded; the army is the same. There are no more constitutional solutions for Brazil.

As far as the opposition is concerned, Bahia Governor Juracy Magalhães tried to form a secretive opposition between various states. The plan failed, though Magalhães's political future, as well as Cavalcanti's who had agreed to the plan, was now to be in ruins.[27]

Preparation[]

The planning of what would become the Estado Nôvo (English: New State) sprouted due to Cunha. The need to remove Cunha from power paved the way for the planning of a new constitution, the cancellation of elections, and, at the same time, the nullification of the federal system. The oganizers of the coup decided that, instead of potentially provoking civil war by operating primarily in the south, they would pursue intercessions in states against Vargas and segregate Cunha's Bahia and Pernambuco allies in preparation of Cunha's removal. With the acession of Monteiro to Army Chief of Staff in July 1937 and the removal of opposing officers in command, Vargas now needed to either act or be deposed. The government continuously stepped in authoritarian direction despite the President's assurance of leaving office.[42]

September[]

The official beginning of the planning of the coup began on 18 September 1937, though it is believed that by early 1936 Vargas was already trying to extend his own tenure by modifying the 1934 constitution.[43] The President's depressed mood in July had turned around after a meeting with Monteiro and Filho, writing about a "risk to life itself" and regaining his sense of adventure in his diary.[40] Vargas and Minister of War Eurico Gaspar Dutra met where Vargas explained his intentions of a coup, hoping for the army's consent. Dutra assured Vargas his support but noted he would need to consult the rest of the military.[43] Dutra was able to get aid from General Daltro Filho, commander of the Third Military Region in Rio Grande do Sul. Nine days later (27 September), Dutra convened senior army officers including Monteiro. There, they established consensus that the potential of another communist uprising, coupled with the lackluster laws defending the country, warranted the military's support of a presidential coup. One general added the opportunity should also be used to combat the extremism of the right.[44] Meanwhile, , who admired European fascism and corporatism and was anti-liberal and anti-communist,[45][46] was at clandestine work on a new, corporative constitution for Brazil.[47]

The problem was there was no apparent reasoning for staging a coup.[35] On 28 September, Monteiro asserted that the coup rumors were completely groundless. On 29 September,[d] however, Dutra, on the Hora do Brasil radio program, publicly revealed a communist document, detailing a violent revolution with rape, massacres, pillaging, and church burnings, and called for a new state of war.[35][49][47][50] Historian Robert M. Levine called the document "a blatant forgery";[49] it has also been dubbed as "fantasy" or "literature" by the Faustos.[35] The origins of the document, the , are unclear.[35] The Faustos say Captain Olímpio Mourão Filho (chief of AIB propaganda)[49] was caught (or allowed himself to intentionally be caught) at the Ministry of War creating a plan for a potential communist uprising which would be publicized in an AIB bulletin, describing how an insurrection would go down and how the Integralists would react to it.[35] Levine states the plan was faked by Integralist agents, passed onto Monteiro via Captain Filho, and played off as being seized from communist sources.[49] According to Bourne, the Integralists forged the "bloodthirsty" communist document in order to strengthen the government in preparation for the coup and to do away with Cunha's army.[47] The plan was anti-Semitic, for the name Cohen was an obvious Jewish name and a potential variation on Béla Kun, the Jewish-Hungarian communist.[35]

October[]

The aftermath of the revelation was severe. Almost immediately, the petrified Congress convened overnight to declare a state of war and suspend constitutional liberties and rights. Only a few hesitant states and liberals objected to the vote.[35][51] State of war commissions were headed by governors in all states to suppress the opposition.[51] Rio Grande do Sul, where Governor Cunha was the target of the commission, and Pernambuco, where Governor Cavalcanti was barred from attending the commission's meetings, were notable exceptions.[47] Cunha was nearly impeached, but the opposition's efforts failed by only one vote. When the state of war commission demanded the state militia be incorporated into federal forces, the Governor had no power to object and the deed was done on 17 October. Archbishop Dom transmitted the news to Cunha who would leave for exile in Montevideo, Uruguay, and left a farewell speech to his state.[47][52][35] The leadership of the Third Military Region declared the Military Brigade of Rio Grande do Sul federalized.[35] Vargas's brother Benjamin wired the President to notify him things in Rio Grande do Sul were going well.[53] At the same time, Vargas worked closely with Valadares.[54]

The military commander in Bahia ferociously attacked the Governor. In Pernambuco, the Governor's mail was censored, editors favorable to the Governor were persecuted, and several of his staff were arrested.[55] At the end of October, Deputy Negrao de Lima paid a visit to the states of the Northeast, making sure the states' governors were in support of a coup and observing their reactions. There was near unanimous consent for the it.[35][54] The anti-communism campaign was also at its apex.[54] For instance, churches spoke openly on the communist threat, university students formed an opposition to the ideology in Curitiba, secondary schools were closed for an investigation into communism in Belém, and spiritist societies, a constant nuisance to the church, were terminated in Rio de Janeiro.[56]

November[]

On 1 November, the President and two generals, including General Cavalcanti, reviewed a parade of 20,000 in the Integralist militia. Meanwhile, rumors circulated about a coup that was about to come, yet government business went on as usual.[50][54] Levine states, "It seemed apparent the country was moving to the far right and to fascism."[50] A week before the coup (3 November), there was a commemoration for Vargas's seventh year in power. However, Vargas was absent from the occasion, instead conversing with advisors on the price of coffee and allocating the evening to a lengthy discussion with Monteiro.[57] In the week leading up, Vargas and Campos met and discussed the new national constitution Campos was the author of. A story in the Correio da Manhã was censored; it talked about a conspiracy in the army. The censorship system was given to the Federal District police from the civilian justice ministry. On 7 November, the President confessed to his diary that the planned coup, in which the Congress would be closed and a new constitution imposed, could not be turned around.[45] At this point, Levine says, Vargas held "near-absolute" control in the country.[53] There was clear support from the army, with a three-to-one ratio in favor of amendments to the 1934 constitution. Intrigued after being briefed by Campos, Integralists believed the events would get them into the national government.[53] In reality, they would be betrayed and arrested during the coup.[58]

The opposition had only mobilized in early November. Almeida suggested to Dutra that both main candidates would withdraw and leave one clear army candidate (Almeida would later deny allowing anyone to negotiate his removal after he became isolated and Vargas told the press Lima's visit was an inquiry into opinions for a substitute presidential candidate). Word of Lima's visit had spread and Sales had sent a manifesto to the military, alleged to be disseminated in the barracks, urging them to stop the coup. This only hurt his cause; instead of 15 November, the set date and the anniversary for the Proclamation of the Republic, Vargas and military leaders changed the date to 10 November. There were also communications between Valadares and São Paulo's intervenor and Rio Grande do Sul pro-government forces. The moderate minister of justice resigned[e] on 8 November from the cabinet after falling on the wrong side of the anti-communists; Campos replaced him.[54][35][53][45] With more good news coming from the states, there was now no opposition standing in the way between the President and the detailed coup d'état.[59]

Execution[]

On the morning of 10 November 1937, cavalry surrounded the Congress and blockaded the entrance. One visitor trying to get into the Palácio Monroe was told by a guard, "When a senator cannot enter, then how can a stranger enter?"[60] At 10:00, copies of the new constitution were printed and distributed amongst the cabinet and they were requested to sign it. The sole dissident, minister of agriculture Odilón Braga, immediately resigned and was replaced by anti-Sales paulista Fernando Costa.[61][45][54] The president of the Senate was notified of the dismissal of the organ.[54] Dutra, meanwhile, acclaimed the "lofty mission entrusted to the national armed forces",[62] though he had been against the use of military in the operation in which Congress was seized.[35] Many military personnel resigned, notably Colonel Eduardo Gomes.[62] In every state beside Minas Gerais, where Governor Valadares was the politician most involved with the coup, new intervenors were named. Though most appointees had succeeded themselves, those in Rio Grande do Sul, São Paulo,[f] Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, and Pernambuco were replaced.[62]

In a radio broadcast, Vargas claimed the political climate "remains restricted to the simple processes of electoral seduction", that political parties lacked ideology, that legislative delay prevented the promises made in the April 1934 presidential message, including a penal code and code of mines, and that regional caudilhos had flourished.[46] Instead, he presented a new program of activity, with new roads and railways into the Brazilian hinterland and the implementation of "a great steelworks" that could use local minerals and offer employment. He promulgated that the Estado Nôvo would restore Brazil to authority, freedom of action, and be of "peace, justice and work".[46] Brazil had purportedly been on the edge of a civil war. Campos also held a press conference where he made public the founding of a National Press Council "for perfect co-ordination with the government in control of news and of political and doctrinal material."[46]

Aftermath[]

A new regime[]

On 13 November 1937, eighty members of the dismissed National Congress visited the Catete Palace in a gesture of support. Two days earlier, a number of Congress members were arrested. They were oblivious to the 1937 coup in the first place; with the knowledge of a potential coup, they spent their last debate arguing on whether or not there should be a discussion on the establishment of a national Institute of Nutrition.[62][63][64] Additionally, virtually no protest to the new regime was apparent.[62][54]

The new government was called the Estado Nôvo, deriving its name from the Portuguese government headed by António de Oliveira Salazar and propped up just four years earlier in 1933. The new corporatist constitution found ideas from those of Italy and Poland, too, gaining it the nickname "a polaca".[65][66] The creators of the new regime yearned to change Brazil by tackling what they believed to be its root issues – an absence of discipline, national pride, leadership, and belief in parliamentarism. Civil rights were abridged and individual liberties were nominal. The proposed Congress never met. Vargas's term was prolonged by six years and he was now allowed to run for reelection. Sales was held in Minas Gerais for six months on house arrest, later being exiled in 1938. The power of states was now nonexistant. Political parties were outlawed on 2 December 1937. However, Vargas saw no reason to build support via political party or an ideological program.[67][68] Levine states, "Vargas, in spite of his tough caudilho ability to deal with personalities around him, held little talent for totalitarian dictatorship in the strict sense of the word."[69] He does not, however, refrain from labelling the new government as authoritarian.[69] Lillian E. Fisher describes the new state as "semi-fascist".[70] Historian Jordan M. Young says the new constitution was "molded this time along totalitarian lines" and Brazil now became a dictatorship. They added, "Brazil was governed from 1937 to 1945 by laws that were issued by the executive office, the government again was one man, Getúlio Vargas."[71] With the new period, Vargas ruled as dictator, and his term ended up finishing only on 29 October 1945.[16][72] Precedents that began during the new period remained in Brazilian politics for many years to come.[73]

Foreign reaction[]

U.S. Ambassador to Brazil Jefferson Caffery was informed directly by Brazil's foreign minister about the events, claiming they desired Caffrey have priority before any other ambassador. According to Caffrey's description of events, the presidential campaign threatened a crisis; Vargas wasn't able to reach consent for a third candidate from the Bahia and Pernaumbuco governors; a plebiscite would be held for the new constitution, replacing the weak 1934 constitution; the government would proceed to adhere to a "very liberal policy with respect to foreign capital and foreigners who have legitimate interests in Brazil." He was skeptical of "effective preservation of democratic institutions under the new constitution."[74] He would prove to have predicted what was to come;[74] the plebiscite was never fulfilled.[75]

A story attributed to Francisco Campos published in The New York Times was the confirmation of a fascist organization in Brazil, fueling the flames. The New York Post and the Daily Worker condemed the neutrality of the United States Department of State and Oswaldo Aranha, Brazilian ambassador to the United States. Aranha wrote to Vargas that "Communists and American Jews" were at fault for the anti-Brazilian campaign. Aranha received the backlash poorly, but his close friend in Washington, D.C., Sumner Welles, was by his side. On 11 November, Welles told the press the coup was an internal Brazilian matter not to be judged by the U.S. Three weeks later, he praised Vargas and criticized those who condemned Brazil as doing it "before the facts were known". Aranha resigned on 13 November.[76][75][g]

Argentine military circles praised the new regime, but this was contrary to the public opinion. Newspapers attacked the new regime in an attempt to distort any move to the right by the administration of President Agustín Pedro Justo. In Chile, the response was unfavorable. Radio and press in Uruguay, the place of Cunha's exile (see Build up: October) and favorable to the ex-Governor, attacked the new regime even harder.[78]

The German Propaganda Minister praised Vargas's political realism and how he could act in the right moment. German press and German-language press in the Southern Hemisphere commended the authoritarian government as a triumph against bolshevism. Italian reaction was likewise. However, the Germans showed diminished enthusiasm in private as they knew of Vargas's efforts to subdue Nazism in Brazil. European fascists are where the only supportive opinions appeared. Elsewhere in Europe, reaction similar to that of the United States appeared in United Kingdom, where commentators in both countries warned Brazil was nearing a fascist dictatorship.[79][80]

See also[]

- List of coups and coup attempts in Brazil

- Vargas Era

Notes[]

- ^ Paulista means person from São Paulo.

- ^ This article uses Portuguese abbreviations. For example, PCB means Partido Comunista Brasileiro, translated to Brazilian Communist Party.

- ^ Golpe means coup.

- ^ Or 30 September.[48]

- ^ Justice Minister Macedo Soares was fired according to Levine (1998) but resigned according to Bourne. Soares resigned according to Levine (1970).[45][54][59]

- ^ After it was assured no resistance would emit from the state, São Paulo's old intervenor returned after thirteen days.[62]

- ^ The resignation was denied on 18 November by Vargas. Aranha would become minister of foreign affairs in March 1938.[77]

References[]

- ^ Pandolfi 2004, p. 183, 186.

- ^ Meade 2010, pp. 123–124, 131.

- ^ Meade 2010, p. 131.

- ^ Meade 2010, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Skidmore 2010, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Bourne 1974, pp. 34, 38, 40, 46–47.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Skidmore 2010, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Meade 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Bourne 1974, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Fausto & Fausto 2014, p. 194.

- ^ Skidmore 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Bourne 1974, p. 47.

- ^ Skidmore 2010, p. 112.

- ^ Fausto & Fausto 2014, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Bourne 1974, p. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young 1967, p. 81.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1970, pp. 104, 107.

- ^ Bourne 1974, p. 72.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fausto & Fausto 2014, p. 208.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fausto & Fausto 2014, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 126, 129.

- ^ Fisher 1944, p. 83.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 128.

- ^ Bourne 1974, p. 76.

- ^ Skidmore 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Fausto & Fausto 2014, p. 209.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Levine 1970, p. 139.

- ^ "CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA DOS ESTADOS UNIDOS DO BRASIL; SEÇÃO II; ARTIGULO 52" (in Portuguese). 16 July 1934. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bourne 1974, p. 80.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bourne 1974, p. 81.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Levine 1970, p. 141.

- ^ Young 1967, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bourne 1974, p. 90.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 138.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fausto & Fausto 2014, p. 210.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1970, p. 142.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 70.

- ^ Bourne 1974, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1998, p. 48.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 138, 143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bourne 1974, p. 82.

- ^ Bourne 1974, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Levine 1998, p. 49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bourne 1974, p. 85.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bourne 1974, p. 83.

- ^ Pandolfi 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Levine 1970, p. 145.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Levine 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1998, p. 145.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Levine 1970, p. 147.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Bourne 1974, p. 84.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 146.

- ^ Levine 1998, p. 146.

- ^ Levine 1998, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1970, p. 148.

- ^ Fisher 1944, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 148–149.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Levine 1970, p. 149.

- ^ Fausto & Fausto 2014, p. 211.

- ^ Young 1967, p. 89.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 150, 162.

- ^ Levine 1998, p. 51.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Bourne 1974, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1970, p. 151.

- ^ Fisher 1944, p. 84.

- ^ Young 1967, pp. 89, 91.

- ^ Hudson 1997.

- ^ Young 1967, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine 1970, p. 150.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bourne 1974, p. 87.

- ^ Levine 1970, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 154.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 152.

- ^ Levine 1970, p. 153.

- ^ Fausto & Fausto 2014, p. 221.

Sources[]

- Bourne, Richard (1974). Getulio Vargas of Brazil, 1883—1954 Sphinx of the Pampas. London, England: C. Knight. ISBN 978-0-85314-195-2.

- Fausto, Boris; Fausto, Sergio (2014). A Concise History of Brazil (2º, revised ed.). São Paulo, Brazil: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10763-524-1.

- Fisher, Lillian Estelle (April 1944). "Getulio Vargas, the Strong Man of Brazil". Social Science. Pi Gamma Mu, International Honor Society in Social Sciences. 19 (2): 80–86. JSTOR i40088445.

- Hudson, Rex A. (1997). "The Era of Getúlio Vargas, 1930-54". Country Studies. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Levine, Robert M. (1970). The Vargas Regime: The Critical Years, 1934—1938. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-23103-370-1.

- Levine, Robert M. (1998). Father of the Poor? Vargas and His Era. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52158-515-6.

- Meade, Teresa A. (2010). A Brief History of Brazil (2º ed.). New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-7788-5.

- Pandolfi, Dulce Chaves (2004). "O Golpe do Estado Novo (1937)". Getúlio Vargas e seu tempo (PDF) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social. pp. 183–189.

- Skidmore, Thomas E. (2010). Brazil: Five Centuries of Change (2º ed.). United States: Oxford University Press.

- Young, Jordan M. (1967). The Brazilian revolution of 1930 and the aftermath. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- 1937 in Brazil

- 1930s coups d'état and coup attempts

- Conflicts in 1937

- Military coups in Brazil

- November 1937 events