81st Infantry Division (United States)

| 81st Readiness Division, 81st Infantry Division 81st Army Reserve Command (81st ARCOM) 81st Regional Support Command (81st RSC) 81st Regional Readiness Command (81st RRC) 81st Readiness Division (81st RD) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1917–1919 1921–1946 1967–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry 1917–1946 (Regular Army) Force Sustainment 1967–Present (Army Reserve) |

| Size | Division 1917–1946 Support Command 1967–Present |

| Nickname(s) | "Wildcat" (special designation)[2] |

| Motto(s) | "Wildcats never quit" |

| March | The Wildcat March |

| Mascot(s) | Sergeant Tuffy the Wildcat |

| Engagements | World War I

|

| Decorations | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | MG Charles Justin Bailey MG Paul J. Mueller |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia of the 81st ARCOM (1970–1996) and 81st RSC[3] |  |

The 81st Readiness Division ("Wildcat"[2]) was a formation of the United States Army originally organized as the '81st Infantry Division' during World War I. After World War I, the 81st Division was allotted to the Organized Reserve as a "skeletonized" cadre division. In 1942, the division was reactivated and reorganized as the 81st Infantry Division, and service in the Pacific during World War II. After World War II, the 81st Infantry Division was allotted to the Organized Reserve (known as the United States Army Reserve after 1952) as a Class C cadre division, and stationed at Atlanta, Georgia. The 81st Infantry Division saw no active service during the Cold War, and was inactivated in 1965.[4]

In 1967 the division's shoulder sleeve insignia was reactivated for use by the 81st Army Reserve Command (81st ARCOM). From 1967 to 1995, the 81st ARCOM was headquartered in East Point, Georgia, commanded and controlled Army Reserve units in Georgia, South Carolina, Puerto Rico and portions of North Carolina, Florida and Alabama. During that time, the 81st ARCOM was responsible for deploying US Army Reserve units to Vietnam, Southwest Asia, and the Balkans. The 81st was relocated in 1996 to Birmingham, Alabama and reorganized as the 81st Regional Support Command (RSC) and was responsible command and control of all Army Reserve units in the southeast United States and Puerto Rico.[1][5]

In 2003, the 81st RSC was reorganized as the 81st Regional Readiness Command (RRC), but retained essentially the same mission as its predecessor. In September 2008, the 81st RRC inactivated at Birmingham, Alabama. In its place, a reorganized 81st Regional Support Command (RSC) was activated at Fort Jackson, South Carolina.[4] Unlike its predecessor units, the new 81st RSC had a fundamentally different mission. Gone was the responsibility for hundreds of Troop Program Units (TPU) units and Soldiers. Instead, the 81st RSC provided Base Operations (BASOPS) support to 497 Army Reserve units in nine southeastern states plus Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. By providing the essential customer care and services, the 81st RSC was intended to help the supported Operational, Functional and Training (OF&T) commands to focus on their core unit mission and ultimately meet force requirements for global combatant commanders.[6] In 2018, the 81st RSC was provisionally redesignated as the 81st Readiness Division, and designated to gain additional responsibilities from other Army Reserve Functional Commands in addition to the enduring BASOPS mission.

On 1 October 2018, the 81st RSC was officially reorganized as the 81st Readiness Division (USAR).[7]

World War I[]

[8] The 81st Infantry Division "Wildcats" was organized as a National Division of the United States Army in August 1917 during World War I at Camp Jackson, South Carolina. The division was originally organized with a small cadre of Regular Army officers, while the soldiers were predominantly Selective Service men drawn from the southeastern United States. After organizing and finishing training, the 81st Division deployed to Europe, arriving on the Western Front in August 1918. Elements of the 81st Division first saw limited action by defending the St. Dié sector in September and early October. After relief of mission, the 81st Division was attached to the American First Army in preparation for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. In the last days of World War I, the 81st Division attacked a portion of the German Army's defensive line on 9 November 1918, and remained engaged in combat operations until the Armistice with Germany at 1100 hours on 11 November 1918. After the cessation of hostilities, the 81st Division remained in France until May 1919; after which the division was shipped back to the United States and inactivated on 11 June 1919.[9]

Interwar period[]

The division was reconstituted in the Organized Reserve on 24 June 1921 and assigned to the states of North Carolina and Tennessee.

World War II[]

The 81st Infantry Division was reactivated for World War II service in June 1942 at Camp Rucker, Alabama. As in World War I, the division was filled primarily with inducted men. The division trained at locations in Tennessee, Arizona and California before embarking for Hawaii in June 1944. After completion of amphibious and jungle training, the 81st Infantry Division departed for Guadalcanal in August 1944. There the division was attached to the III Marine Amphibious Corps reserve.[10] In September 1944 the 321st and 322nd Infantry Regiment of the 81st Infantry Division performed a combat landing on Angaur Island as part of the operations to secure the Palau Islands chain. After finishing the battle of Angaur, the 81st Infantry Division was ordered to assist the 1st Marine Division in their efforts to seize Peleliu. The 81st Infantry Division eventually relieved the 1st Marine Division, and assumed command of combat operations on Peleliu. The 81st Infantry Division remained engaged in the Battle of Peleliu until the end of organized Japanese resistance on 18 January 1945. In early February 1945, the 81st Infantry Division sailed to New Caledonia to rest and refit. In May 1945, the 81st Infantry Division was deployed to the Philippines to take part in mopping up operations on Leyte Island, and to prepare for the planned invasion of Japan. After the end of World War II, the 81st Infantry Division deployed to Aomori Prefecture in Japan as part of the Allied occupation force. The 81st Infantry Division was inactivated in Japan on 30 January 1946.[11]

On 10 November 1947, the 81st Infantry Division was reconstituted in the Organized Reserve Corps (known as the United States Army Reserve after 1952) with the division headquarters at Atlanta, Georgia. Under War Department guidelines, the 81st was organized as a Class C reserve unit with 60% of the authorized officer cadre, but no authorized enlisted members. In the event of a wartime mobilization, the division would expand to wartime strength with called up reservists and new inductees. However, during the 1950s and 60s, the 81st Infantry Division was not called up for service during the Korean War or Berlin Crisis. As part of the 1962 reorganization of the Reserve Components initiated by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, the 81st Infantry Division was selected for inactivation, which was completed on 31 December 1965.[12]

Combat history[]

World War I[]

- Activated: September 1917. Camp Jackson, South Carolina.

- Overseas: August 1918.

- Major Operations: Meuse-Argonne, Alsace-Lorraine.

- Casualties: Total-1,104 (KIA-195, WIA-909).

- Commanders: Brig. Gen. Charles H. Barth (28 August 1917), Maj. Gen. Charles J. Bailey (8 October 1917), Brig. Gen. Charles H. Barth (24 November 1917), Brig. Gen. George W. McIver (28 December 1917), Maj. Gen. Charles J. Bailey (11 March 1918), Brig. Gen. George W. McIver (19 May 1918), Brig. Gen. (24 May 1918), Maj. Gen. Charles J. Bailey (30 May 1918), Brig. Gen. George W. McIver (9 June 1918), Maj. Gen. Charles J. Bailey (3 July 1918).

- Inactivated at Hoboken, New Jersey on 11 June 1919.

Order of battle[]

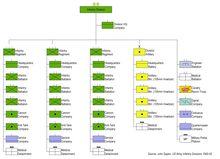

The division was composed of the following units:[13]

- Headquarters, 81st Division

- 161st Infantry Brigade

- 321st Infantry Regiment

- 322nd Infantry Regiment

- 317th Machine Gun Battalion

- 162nd Infantry Brigade

- 323rd Infantry Regiment

- 324th Infantry Regiment

- 318th Machine Gun Battalion

- 156th Field Artillery Brigade

- 306th Train Headquarters and Military Police

- 306th Ammunition Train

- 306th Supply Train

- 306th Engineer Train

- 306th Sanitary Train

- 321st, 322nd, 323rd, and 324th Ambulance Companies and Field Hospitals

World War II[]

- Activated: 15 June 1942, Camp Rucker, Alabama.

- Overseas: 3 July 1944.

- Campaigns: Western Pacific, South Philippines.

- Days of combat: 166.

- Awards: DSC-7 ; DSM-2 ; SS-281; LM-7; SM-40 ; BSM-658 ; AM-15.

- Commanders: Maj. Gen. Gustave H. Franke (June–August 1942), Maj. Gen. Paul J. Mueller (August 1942 to inactivation).

- Inactivated: 30 January 1946 in Japan.

Order of Battle[]

- Headquarters, 81st Infantry Division

- 321st Infantry Regiment

- 322nd Infantry Regiment

- 323rd Infantry Regiment

- Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 81st Infantry Division Artillery

- 306th Engineer Combat Battalion

- 306th Medical Battalion

- 81st Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

- Headquarters, Special Troops, 81st Infantry Division

- 781st Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

- 81st Quartermaster Company

- 81st Signal Company

- Military Police Platoon

- Band

- 81st Counterintelligence Corps Detachment

Combat chronicle[]

The 81st Infantry Division landed in Hawaii, 11 June-8 July 1944. The division minus Regimental Combat Team (RCT) 323 invaded Angaur Island in the Palau group, as part of the Palau Islands campaign 17 September, and pushed through to the western shore in a quick movement, cutting the island in half. The enemy was driven into isolated pockets and mopping-up operations began on 20 September. RCT 321, attached to the 1st Marine Division, went into action on Peleliu Island in the Palaus and assisted in splitting defense forces and isolating them in mountainous areas in the central part of the island. The team aided in mopping up Ngesebus Island and capturing Kongauru and Garakayo Islands. RCT 323 under naval task force command occupied the Ulithi atoll, 21–23 September 1944. Elements of the team landed on Ngulu Atoll and destroyed enemy personnel and installations, 16 October, completing the outflanking of the enemy base at Yap. On 18 October, RCT 323 left to rejoin the 81st on Peleliu, which assumed command of all troops on that island and Angaur, 20 October 1944. Resistance was ended on Peleliu, 27 November. Between 4 November 1944 and 1 January 1945, the division seized Pulo Anna Island, Kyangel Atoll, and Pais Island. The 81st left in increments from 1 January to 8 February for New Caledonia for rehabilitation and training. The division arrived in Leyte on 17 May 1945, and after a period of training participated in mopping-up operations in the northwest part of the island, 21 July 1945 to 12 August 1945. After rest and training, the 81st moved to Japan, 18 September, and performed occupation duties in Aomori Prefecture until inactivation.[11]

Casualties[]

- Total battle casualties: 2,314[15]

- Killed in action: 366[15]

- Wounded in action: 1,942[15]

- Missing in action: 6[15]

Story of the wildcat[]

As the fighting divisions of the United States Army organized in 1917, commanders adopted distinctive nicknames and insignia, not only to foster esprit-de-corps within their units, but to help identify unit equipment and baggage. The 81st Division, composed mostly of Southern inductees, first adopted the nickname "Stonewall Division" in honor of Confederate General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson. While at Camp Jackson, much of the division training was conducted in the vicinity of Wildcat Creek. Furthermore, some more daring country boys in uniform trapped a Carolina wildcat near the creek, and adopted the snarling beast as the division mascot. For those reasons, the division adopted a wildcat as their unique insignia. The wildcat proved so popular with the members of the division that the "Stonewall" nickname was quickly supplanted. The cat symbol and the motto "Obedience, Courage, Loyalty" were officially adopted in the War Department General Order #16 of 24 May 1918.[16]

The 81st Division commander, Major General Charles J. Bailey, went a step further in creating a distinctive shoulder patch for his men after seeing similar items in use by Allied troops on the Western Front. General Bailey canvassed his officers for thoughts on a divisional patch. Colonel Frank Halstead, commander of the 321st Infantry regiment, logically proposed to use a wildcat as a symbol. Sergeant Dan Silverman, a soldier in the headquarters of the 321st Infantry, created several concept sketches for review by General Bailey. One of Silverman's sketches which showed a wildcat superimposed on a disk was selected for approval by General Bailey.[17] Out of the concept sketch was created a circular olive drab cloth patch with a wildcat silhouette surrounded by a black border. To further differentiate the elements of the division, specific colors were assigned the subordinate brigades, support trains and separate battalions. For example, the divisional headquarters and headquarters troop adopted a black patch with a yellowish wildcat with the superimposed letters "HQ". On his own authority, Bailey authorized the creation and wear of the wildcat patches.[18]

The new wildcat insignia not only served as a ready means of identification, but helped to foster unit pride and esprit-de-corps. However, General Bailey quickly found himself in trouble over his unauthorized patch. When the 81st Division arrived in New York City to embark for Europe, the port commander not only ordered the removal of the patches, but cabled the War Department to report the breach of uniform regulations. By the time the War Department replied with orders to remove the patch, the 81st Division had already sailed from New York. Once at sea, General Bailey cheekily ordered his men to restore the wildcat patches to their uniforms.[19]

However, the matter of the wildcat patch was not settled. As the 81st Division was moving into the Vosges sector of France, a War Department telegram arrived from the Adjutant General of the American Expeditionary Forces. The telegram frostily requested General Bailey to "furnish authority, if any, for wearing the "wildcat" in cloth on both the left sleeve and overseas cap...it is gathered that no previous authority was officially given to any organization for this addition to the uniform." Bailey redoubled his efforts to keep the insignia by sending an indorsement to General John Pershing on 4 October 1918 advising that "no official sanction had been given for the wearing of the emblem on the uniform. Bailey continued by explaining in detail the events leading up to the adoption...of the distinguishing symbol in this manner and the advantages of the usage of such as symbol."[20]

Determined to win the argument, Bailey obtained permission to personally defend his decision to General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.). As the story goes, Bailey touted the advantages of a shoulder patch in boosting the morale of the soldiers. General Pershing approved the use of the patch, reportedly saying "all right, go ahead and wear it; and see to it that you live up to it."[21]

Bailey's initiative quickly spread among the A.E.F. On 18 October 1918, the commander of the First Field Army distributed an order from General Pershing that directed each division commander to submit a sleeve insignia design for review and approval. On 19 October, the 81st Division requested confirmation of their existing wildcat design, and received approval from the GHQ on the same day - thus confirming the 81st Division Wildcat patch as the first divisional patch of the Army.[22] In 1922 the War Department approved the final version of the Wildcat patch, a black cat on an olive drab disc within a black circle, a design which has remained the same ever since - with one minor variation. When worn on the Desert Combat Uniform, the patch was tan and brown. In contrast to other Army organizations which displayed a colored patch on the old green dress uniform and a "subdued" patch for the field uniform, the 81st Wildcat insignia was the same regardless of uniform type.[23] In 1967, a memo from the Adjutant General of the Army authorized the wearing of the 81st Infantry Division patch by the 81st Army Reserve Command (ARCOM) of the United States Army Reserve. This authorization is extended today to the 81st Readiness Division (RD) currently located at Fort Jackson, South Carolina.[5]

See also[]

References[]

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army Center of Military History document: "The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950 reproduced".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army Center of Military History document: "The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950 reproduced".

- ^ Jump up to: a b 81st Regional Support Command, Shoulder Sleeve Insignia Archived 29 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, United States Army Institute of Heraldry (TIOH), dated 17 September 2008, last accessed 31 May 2017

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Special Unit Designations". United States Army Center of Military History. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ 81st Regional Support Command, Distinctive Unit Insignia Archived 29 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, TIOH, dated 17 September 2008, last accessed 31 May 2017

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lineage & Honors HQ 81st Regional Support Command". History. Army.Mil. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 81st Regional Support Command US Army Reserve Official Website, last accessed 31 May 2017

- ^ Coker, Kathryn R. (2013). The Indispensable Force: The Post-Cold War Operational Army Reserve, 1990 – 2010. Fort Bragg, North Carolina: Office of Army Reserve History. pp. 355–8.

- ^ Permanent Order F-008-001, Headquarters, United States Army Reserve Command (USARC), 8 January 2019.

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil//html/books/077/77-3/cmhPub_077-3.pdf Joining the Great War

- ^ American Battle Monuments Commission (1944). 81st Division Summary of Operations in the World War. Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 1–5, 9.

- ^ 317th Military History Detachment. Wildcats Never Quit: A Brief History of the 81st Infantry Division and its Successor, the 81st US Army Reserve Command. East Point, Georgia: 317th Military History Detachment. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b No Author (1950). The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 554–5.

- ^ Crossland, Richard; Curry, James T. (1984). Twice the Citizen: A History of the United States Army Reserve, 1908-1983. Washington D.C.: Office of the Chief of the Army Reserve. pp. 159–160.

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/023/23-2/CMH_Pub_23-2.pdf Order of Battle in the Great War P339

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/cbtchron/infcomp.html Component Elements of Infantry Divisions in World War II

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ^ Department of the Army (n.d.). Resume: Shoulder Sleeve Insignia 81st Infantry Division. Fort Belvoir, Virginia: Institute of Heraldry.

- ^ No author (n.d.). 81st Regional Support Command History. Fort Jackson, South Carolina: 81st Regional Support Command. p. 2.

- ^ Johnson, Clarence Walton (1919). The History of the 321st Infantry. Columbia SC: R.L. Bryan Company. p. 133.

- ^ No author (n.d.). 81st Regional Support Command History. Fort Jackson SC: 81st Regional Support Command. pp. 3–4.

- ^ Department of the Army (n.d.). Resume: Shoulder Sleeve Insignia 81st Infantry Division. Fort Belvoir, Virginia: Institute of Heraldry. p. 1.

- ^ No author (n.d.). 81st Regional Support Command History. Fort Jackson, South Carolina: 81st Regional Support Command. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Center of Military History (15 May 2006). WWI Lineage. Washington D.C.: Department of the Army. pp. Chapter III, pp 22–23.

- ^ Department of the Army (n.d.). Resume: Shoulder Sleeve Insignia 81st Infantry Division. Fort Belvoir, Virginia: Institute of Heraldry. pp. 1–2.

Further reading[]

- Triplet, William S. (2000). Ferrell, Robert H. (ed.). A Youth in the Meuse-Argonne. Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press. pp. 278–80. ISBN 0-8262-1290-5. LCCN 00029921. OCLC 43707198.

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army

- United States Army divisions during World War II

- United States Army divisions of World War I

- Military units and formations established in 1917

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1946

- 1917 establishments in South Carolina

- 1946 disestablishments in Japan