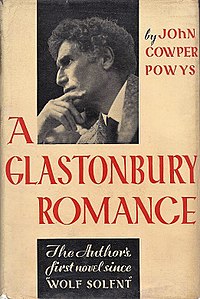

A Glastonbury Romance

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

| |

| Author | John Cowper Powys |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster (US); The Bodley Head (UK) |

Publication date | 6 March 1932 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 1174 (1932, New York) |

| ISBN | 0-7156-3648-0 |

| OCLC | 76798317 |

| 823.912 | |

| LC Class | PR6031.O867 |

| Preceded by | Wolf Solent |

| Followed by | Weymouth Sands |

A Glastonbury Romance was written by John Cowper Powys (1873–1963) in rural upstate New York and first published by Simon and Schuster in New York City in March 1932. An English edition published by John Lane followed in 1933. It has "nearly half-a-million words" and is "probably the longest undivided novel in English".[1]

It is the second of Powys's Wessex novels, along with Wolf Solent (1929), Weymouth Sands (1934) and Maiden Castle (1936). Powys was an admirer of Thomas Hardy and these novels are set in Somerset and Dorset, parts of Hardy's mythical Wessex.[note 1] The action occurs over roughly a year, and the first two chapters of A Glastonbury Romance take place in Norfolk, where the late Canon William Crow's will is read, and the Crow family learn that his secretary-valet John Geard has inherited his wealth.[2] Also in Norfolk, a romance begins between cousins, John and Mary Crow. However, after an important scene at the ancient monument of Stonehenge, the rest of the action takes place in or near the Somerset town of Glastonbury, which is some ten miles north of the village of Montacute. Powys's father, the Reverend Charles Francis Powys (1843–1923), was parish priest of Montacute from 1885 to 1918, and it was here that Powys grew up. The grail legends associated with the town of Glastonbury are of major importance in this novel, and Welsh mythology has, for the first time, a significant role.[3]

Introduction[]

It "was conceived on an uncompromisingly huge scale, with a cast of hundreds".[4] In his preface to the 1955 edition Powys states the novel's "heroine is the Grail",[5] however, in 1932 he described "Glastonbury herself" as "the hero of the story.[6] Its central concern is with the various myths and legends along with history associated with Glastonbury. It is also possible to see most of the main characters, John Geard, Sam Dekker, John Crow, and Owen Evans as undertaking a Grail quest.

However, the opening chapters are concerned with John Crow's arrival in Northwold, Norfolk, to attend his grandfather's funeral and the reading of the will. Northwold was where Powys spent memorable holidays as a child at his maternal grandfather, William Cowper Johnson's, rectory. Johnson was Rector of Northwold from 1880 until 1892. In 1878 was made an Honorary Canon of Norwich Cathedral. Like John Crow, Powys would have arrived at Brandon railway station and similarly boated and fished on the River Wissey. In 1929 he had revisited Northwold with his brother Littleton.[7]

Central to the novel is John Geard's plan to revive Glastonbury as a centre of religious pilgrimage. Part of his plan is an elaborate pageant that includes the various myths and legends associated with the town. It is worth noting that beginning in 1924 annual pilgrimages "to the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey" began to take place, initially organized by some local churches.[8] Pilgrimages continue today to be held; in the second half of June for the Anglicans and early in July for the Catholics and they attract visitors from all over Western Europe. Services are celebrated in the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions.[8] The abbey site is visited by over 100,000 a year.[9] With regard to Geard's pageant, W. J. Keith notes that "the chapter entitled 'The Pageant' occurs exactly halfway" in the novel, and that because "of its structural and thematic importance is therefore central in two senses of that word".[10] Margaret Drabble also recognizes the importance of this chapter, describing its 55 pages as "a narrative tour de force. She notes that it involves "not only the 50 and more named characters ... but a cast of thousands" with "the whole town ... either taking part or providing the audience".[4] There are Arthurian scenes at the beginning, followed by the Christmas 'Passion Play', and a final a prehistoric portion, which is not performed. "The pageant ends ... unintentionally, with the physical collapse of Evans" playing the role of Christ on the cross.[11]

The novel has several climaxes that relate to the completion of the Grail quest of major characters and the murder of Tom Barter.

At the novel's end, much of the city is flooded, in reference to the myth that held Glastonbury to be the original Island of Avalon of Arthurian legend. The novel closes with a drowning John Geard looking to Glastonbury Tor (itself referred to repeatedly as the domain of the Welsh king of the Welsh Otherworld (Annwn), Gwyn-ap-Nudd), in hopes of seeing the Grail. A Glastonbury Romance is also the first of several novels by Powys that reflect his growing interest in Welsh mythology, the others are Maiden Castle (1935), Morwyn (1937), Owen Glendower (1941), and Porius (1951). The Welshman Owen Evans, one of the novel's main characters, introduces the idea that the Grail has a Welsh (Celtic), pagan pre-Christian origin.

Influences[]

Not only is A Glastonbury Romance concerned with the legend that Joseph of Arimathea brought the Grail, a vessel containing the blood of Christ, to the town, but the further tradition that King Arthur was buried there. Powys's wide reading in the literature relating to the Grail, King Arthur, fertility ritual, and Celtic mythology shaped the mythological ideas that underlie this novel. This includes John Rhys's Studies in the Arthurian Legend, the works of the Cambridge classical scholars, Jane Harrison, Francis Cornford, and Gilbert Murray, Roger Loomis on the Fisher King and W. E. Mead on Merlin. In addition Alfred Nutt "on the Celtic version" of the Grail Legend. However, "it was Jessie Weston's controversial theories of the Grail's origins ... that particularly absorbed him".[12]

In writing this novel Powys was also clearly influenced by both James Joyce's Ulysses and T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Just as Joyce established a series of parallels between Homer's Odyssey and his novel, Powys used the Grail as "a peg upon which to hang his huge narrative".[13] In a letter to Kenneth Hopkins, Powys comments "There is all the way through the book a constant undercurrent of secret references to the Grail Legends, various incidents playing roles parallel to those in the old romances of the Grail".[14] Eliot in his first note to his poem attributes the title to Jessie Weston's book on the Grail legend, From Ritual to Romance. The allusion is to the wounding of the Fisher King and the subsequent sterility of his lands; and to the restoring the King and make his lands fertile again.

Island of Avalon[]

Though no longer an island the high conical bulk of Glastonbury Tor had been surrounded by marsh prior to the draining of fenland in the Somerset Levels. In ancient times, Ponter's Ball Dyke would have guarded the only entrance to the island. The Romans eventually built another road to the island.[15] Glastonbury's earliest name in Welsh was the Isle of Glass, which suggests that the location was at one point seen as an island. At the end of 12th century, Gerald of Wales wrote in De instructione principis:

What is now known as Glastonbury was, in ancient times, called the Isle of Avalon. It is virtually an island, for it is completely surrounded by marshlands. In Welsh it is called Ynys Afallach, which means the Island of Apples and this fruit once grew in great abundance. After the Battle of Camlann, a noblewoman called Morgan, later the ruler and patroness of these parts as well as being a close blood-relation of King Arthur, carried him off to the island, now known as Glastonbury, so that his wounds could be cared for. Years ago the district had also been called Ynys Gutrin in Welsh, that is the Island of Glass, and from these words the invading Saxons later coined the place-name "Glastingebury".[16]

Holy Grail[]

The Holy Grail is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Different traditions describe it as a cup, dish or stone with miraculous powers that provides eternal youth or sustenance in infinite abundance, often in the custody of the Fisher King. The term "holy grail" is often used to denote an elusive object or goal that is sought after for its great significance.[17]

A "grail", wondrous but not explicitly holy, first appears in Perceval, le Conte du Graal, an unfinished romance written by Chrétien de Troyes around 1190. Chrétien's story attracted many continuators, translators and interpreters in the later 12th and early 13th centuries, including Wolfram von Eschenbach, who perceived the Grail as a stone. In the late 12th century, Robert de Boron wrote in Joseph d'Arimathie that the Grail was Jesus's vessel from the Last Supper, which Joseph of Arimathea used to catch Christ's blood at the crucifixion. Thereafter, the Holy Grail became interwoven with the legend of the Holy Chalice, the Last Supper cup, a theme continued in works such as the Lancelot-Grail cycle and consequently Le Morte d'Arthur.[18]

Joseph of Arimathea was, according to all four canonical gospels, the man who assumed responsibility for the burial of Jesus after Ηis crucifixion. A number of stories that developed during the Middle Ages connect him with Glastonbury.[19] and also with the Holy Grail legend.

Fisher King[]

In Arthurian legend, the Fisher King also known as the Wounded King or Maimed King is the last in a long bloodline charged with keeping the Holy Grail. Versions of the original story vary widely, but he is always wounded in the legs or groin and incapable of standing. All he is able to do is fish in a small boat on the river near his castle, Corbenic, and wait for some noble who might be able to heal him by asking a certain question. In later versions, knights travel from many lands to try to heal the Fisher King, but only the chosen can accomplish the feat. This is achieved by Percival alone in the earlier stories; he is joined by Galahad and Bors in the later ones.

The Fisher King appears first in Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail in the late 12th century, but the character's roots may lie in Celtic mythology. He may be derived more or less directly from the figure of Brân the Blessed in the Mabinogion. In the Second Branch, Bran has a cauldron that can resurrect the dead (albeit imperfectly; those thus revived cannot speak) which he gives to the king of Ireland as a wedding gift for him and Bran's sister Branwen. Later, Bran wages war on the Irish and is wounded in the foot or leg, and the cauldron is destroyed. He asks his followers to sever his head and take it back to Britain, and his head continues talking and keeps them company on their trip. The group lands on the island of Gwales, where they spend 80 years in a castle of joy and abundance, but finally they leave and bury Bran's head in London. This story has analogues in two other important Welsh texts: the Mabinogion tale "Culhwch and Olwen", in which King Arthur's men must travel to Ireland to retrieve a magical cauldron, and the poem The Spoils of Annwn, which speaks of a similar mystical cauldron sought by Arthur in the otherworldly land of Annwn.

The injury is a common theme in the telling of the Grail Quest. Although some iterations have two kings present, one or both are injured, most commonly in the thigh. The wound is sometimes presented as a punishment, usually for philandering. In Parzival, specifically, the king is injured by the bleeding lance as punishment for taking a wife, which was against the code of the "Grail Guardians".[20] In some early story lines, Percival asking the Fisher King the healing question cures the wound. The nature of the question differs between Perceval and Parzival, but the central theme is that the Fisher King can be healed only if Percival asks "the question".[21][page needed]

The location of the wound is of great importance to the legend. In most medieval stories, the mention of a wound in the groin or more commonly the "thigh" (such as the wounding of the ineffective suitor in Lanval from the Lais of Marie de France) is a euphemism for the physical loss of or grave injury to one's penis. In medieval times, acknowledging the actual type of wound was considered to rob a man of his dignity, thus the use of the substitute terms "groin" or "thigh", although any informed medieval listener or reader would have known exactly the real nature of the wound. Such a wound was considered worse than actual death because it signaled the end of a man's ability to function in his primary purpose: to propagate his line. In the instance of the Fisher King, the wound negates his ability to honour his sacred charge.

King Arthur[]

The legendary Arthur developed as a figure of international interest largely through the popularity of Geoffrey of Monmouth's fanciful and imaginative 12th-century Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain).[22] In some Welsh and Breton tales and poems that date from before this work, Arthur appears either as a great warrior defending Britain from human and supernatural enemies or as a magical figure of folklore, sometimes associated with the Welsh otherworld Annwn (see reference to Gwyn ap Nudd above).[23] How much of Geoffrey's Historia (completed in 1138) was adapted from such earlier sources, rather than invented by Geoffrey himself, is unknown. According to Geoffrey in the Historia, and much subsequent literature which he inspired, King Arthur was taken to Avalon in hope that he could be saved and recover from his mortal wounds following the tragic Battle of Camlann.

Around 1190, monks at Glastonbury Abbey claimed to have discovered the bones of Arthur and his wife Guinevere. The discovery of the burial is described by chroniclers, notably Gerald, as being just after King Henry II's reign when the new abbot of Glastonbury, Henry de Sully, commissioned a search of the abbey grounds. At a depth of 5 m (16 ft), the monks were said to have discovered an unmarked tomb with a massive treetrunk coffin and, also buried, a lead cross bearing the inscription:

Hic jacet sepultus inclitus rex Arturius in insula Avalonia.

("Here lies entombed the renowned king Arthur in the island of Avalon.")

Merlin[]

Links between King Arthur’s magician Merlin, and Glastonbury are “practically non-existent”,[24] but for the legend that King Arthur was buried there. However, Merlin is important in the lives of two of the novel’s main characters, Owen Evans and John Geard. Evans is writing a life of Merlin and believes that hidden in the ancient Welsh grail myths is a spiritual wisdom that will enable him to free himself from the nightmare of his sadistic obsession and find happiness (A Glastonbury Romance, p, 151). Geard spends a night in a room at Marks Court associated with fear and death, because it was where Merlin returned and punished King Mark's crimes by turning him into "a pinch of thin grey dust" (p. 406). After struggling within fear, upon hearing the voice of Merlin "Geard reaches out to comfort the disconsolate ghost ... and from then on does in a sense become Merlin himself".[25] C. A. Coates comments that after this experience Geard "has achieved something in the psychic sphere and established his right to be called a magician".[26] This combined with the legend about the Holy grail containing drops of Christ’s blood, gives Geard the Christ-like power of curing Tithie Petherton of her cancer, and bringing an apparently dead boy back to life (pp. 707, 893-4).

In his Autobiography Powys states that "my dominant life-illusion was that I was, or at least would eventually be, a magician".[27] Later, after describing how reading Thomas Hardy helped him overcome his sadistic thoughts, Powys says that he felt himself "to be what the great Magician Merlin was before he met his 'Belle Dame sans Merci' " (Autobiography, p. 309). Merlin again appears in Morwyn (1937), and as Myrddin in Porius: A Romance of the Dark Ages (1951), while in Owen Glendower (1941), Glendower is presented as a magician by Powys, following Shakespeare’s suggestion, in Henry IV: Part 1 (III.i. 530), There is also, earlier, in Wolf Solent (1929) reference to Christie's mother being Welsh and claiming descent from Merlin.[28]

Themes[]

In 1932 Powys said that, amongst other things, he wrote his Romance, "To express certain moral, philosophical and mystical ideas that seem to me unduly neglected in these days" ([29] In particular this is presented as a "psychic battle ... over the Grail ... between the 'the forces of mystery,' and 'forces of reason' [Romance] (747)".[30] C. A. Coates says that it "is a novel in which the main element is the possibility of mystical experience" and that it is "one of the great mystical novels".[31] While, for Glen Cavaliero, "Glastonbury as a place [is] uniquely constituted for revealing [Powys's] vision of reality. That vision might be described as a naturalizing of the supernatural, the incorporation into a single vision of two normally separate areas of experience".[32] G. Wilson Knight, however, has a different focus, and sees A Glastonbury Romance as "the greatest study of evil that has ever been composed".[33]

Kenneth Hopkins draws attention to the "half a dozen love stories ... each concerned with a different aspect of love". Along with which there is "love go God, love of ones neighbour, love of power, love of self, love of money; selfish or generous or hopeless or triumphant love".[34]

Summary of the plot[]

The action begins in Norfolk with the funeral Canon William Crow and the reading of his will, and where the romance between the cousins John and Mary Crow begins. The Crow family members are shocked to learn that William' Crow's secretary-valet, John Geard, has inherited most of the deceased's wealth. John Crow then sets off to walk to Glastonbury, where he will rejoin Mary. While crossing Salisbury Plain he is offered a ride in Owen Evans' car and the two men visit Stonehenge.

A central aspect of A Glastonbury Romance is the attempt by John Geard, ex-minister now the mayor of Glastonbury, to restore Glastonbury to its medieval glory as a place of religious pilgrimage. On the other hand, the Glastonbury industrialist Philip Crow, along with John and Mary Crow, and Tom Barter, all whom are from Norfolk, view the myths and legends of the town with contempt. Philip's vision is of a future with more mines and more factories. John Crow, however, as he is penniless, takes on the task of organizing a pageant for Geard. At the same time an alliance of Anarchists, Marxists, and Jacobins try to turn Glastonbury into a commune.

Like Powys, Owen Evans is a devoted student of Welsh mythology. He also resembles Powys in that he has strong urges toward violence and sadism, and is often tempted by sadistic pornography. But Evans is not the only character that resembles his creator, as both John Geard and John Crow reflect, in different ways, aspects of Powys's personality.

A Glastonbury Romance has several climactic moments, before the major final one. Firstly there is Sam Dekker's decision, following his Grail vision, to give-up of his adulterous affair with Nell Zoyland, and to lead a monk-like existence. Then there's Evans' failed attempt to destroy his sadistic urge, by playing the part of Christ on the Cross at the Easter Pageant. Followed, however, by his wife Cordelia's ability to defeat his desire to witness a murder. The attempted murder of John Crow is equally climatic. But this involves Tom Barter's death, when he saves his friend John Crow, who is Mad Bet's intended victim.

Finally the novel concludes with the a flooding of the low lying country surrounding Glastonbury, so that it becomes once again the legendary Isle of Avalon. This causes the death of Geard, and ends his ambitious plans for Glastonbury. However, the ending is ambiguous, rather than tragic, because Geard had earlier had asked John Crow: "do you suppose anyone's ever committed suicide out of an excess of life, simply to enjoy the last experience in full consciousness?" (1955 edition, p. 1041).

In the novel's final pages there is a panegyric to "the great goddess Cybele" (1955 edition, p. 1118), the "Goddess Earth" (See also - Gaia, Demeter, Persephone, Rhea),[35] whom "The powers of reason and science gather in the strong light of the Sun to beat ... down. But evermore she rises again" (p. 1119).

Characters[]

The numerous inhabitants of Glastonbury, include: "a sadist, a madwoman, a vicar, a procuress, eccentric servants, spinster ladies, lovelorn maidens, lesbians ... anarchists, communists, romantic lovers, old men, and young children".2007

- John Geard, a mystic who influenced the late Canon Crow of Glastonbury and received the man's riches when he died. Geard becomes mayor of the town during the course of the novel and becomes obsessed with the Grail Legend, commissioning new monuments for the town and promoting his own religious brand of Grail-worship. He is married to Megan Geard—a marriage that is still physically passionate unlike that of Geard's rival, Philip Crow. Geard becomes fascinated with the youthful and delicate daughter of the Marquis of P., Rachel Zoyland. Megan Geard has Welsh ancestry, as her maiden name was Rhys.[36] The Geard's were a prominent family of Baptists in Montacute,[37] where Powys's father was vicar for 32 years.[38]

- Cordelia Geard, daughter of John and Megan Geard. Her name Cordelia may indicate a mythological identification with Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd in The Mabinogion.[39] Her admirer, Owen Evans, identifies her with the Grail Messenger.[40] [41] Creiddylad is the name that Porius gives to the giantess in Powys's novel, Porius.

- John Crow, a young man from Norfolk who comes from France to attend funeral of his grandfather Canon William Crow. There he meets his cousin Mary Crow, who he later marries. He walks to Glastonbury, where he works for John Geard. A skeptic and cynic, he sees his work for Geard as a way of mocking the Grail-worship he is supposed to promote.

- Philip Crow, a cousin to John and an industrialist, who owns Wookey Hole Caves. He is widely hated by the citizens of the town for his attempt to industrialise it. He too hates the Grail legend, and seeks to unseat Geard.

- Tom Barter, a childhood friend of John Crow, from Norfolk. He initially works for Philip Crow but leaves to join John Geard. He is a somewhat depressed womaniser who carries a flame for Mary Crow but marries Tossie Stickles, after she becomes pregnant.

- Owen Evans, a Welshman, obsessed student of Welsh mythology, mystic, antiquarian, and a friend of John Crow. He has strong sadistic urges, and is tempted by an anonymous pornographic book. He is writing a book on Merlin, the magician of Arthurian legend.

- Mat Dekker, the town vicar. He is also wary of Geard's new religion and is also described as being an enemy of the anthropomorphised sun.

- Sam Dekker, the vicar's son. He carries an on-and-off affair with Nell Zoyland, wife of Will Zoyland, and goes through several spiritual conversions during the course of the novel. According to Morine Krissdóttir, "Sam is the virtuous Perceval of medieval myth; the Fisher King is this story Christ himself".[42]

- Persephone Spear, wife of Communist leader Dave Spear and longtime mistress to Philip Crow.

- Mad Bet, (Bet Chinnock) a bald, witch-like madwoman who encourages Finn Toller to commit murder. She is identified with the Grail Messenger.[43]

- Finn Toller (alias, Codfin), who accidentally kills Tom Barter when he attempts to murder John Crow.

- Edward Athling, a farmer-poet who creates the "libretto" for the Glastonbury Pageant.

Romance[]

The novel's title "points to a distinction between romance and novel",[44] and, in his Autobiography, Powys describes Walter Scott's romances, as "by far the most powerful literary influence of my life".[45] Scott defines the romance as "a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvellous and uncommon incidents", in contrast to mainstream novels which realistically depict the state of a society.[46] These works frequently, but not exclusively, take the form of the historical novel.[47] The following definition of the word "romance" is also serves describes some of the characteristic elements of the romance: "the character or quality that makes something appeal strongly to the imagination, and sets it apart from the mundane; an air, feeling, or sense of wonder, mystery, and remoteness from everyday life; redolence or suggestion of, or association with, adventure, heroism, chivalry, etc.; mystique, glamour" (OED). This definition is associated with the Romantic movement, as well as to the medieval romance tradition.[48]

Anthropomorphism[]

The novel also contains numerous examples of anthropomorphism, that is "the attribution of human characteristics or behavior to a god, animal, or object" (OED), reflecting Powys' belief that even inanimate objects possessed a soul.[49] This includes "certain astronomical powers or bodies" who are "possessd of sub-human or super-human consciousness", including "The Sun, the Moon, the Evening Star, the Milky Way, the Constellations".[50] Also, in the first paragraph of the novel, there is reference to the dualism of the First Cause's "divine diabolical soul", the novel's equivalent to a Judeo-Christian God.[51] In Powys's own word, from his "review" in 1932 of the novel, combining "God and the Devil".[52]

Lawsuit[]

In 1934, Powys and his English publishers were successfully sued for libel by Gerard Hodgkinson, real-life owner of the Wookey Hole caves, who claimed that the character of Philip Crow had been based on him. The damages awarded crippled Powys financially, and he was forced to make substantial changes to the English edition of his next novel, which was initially published in America as Weymouth Sands (1934).[53] The title of the English version was changed to Jobber Skald (1935) and all references to the real-life Weymouth were cut.[54]

Reception[]

One of Powys's major novels, it was praised on publication by J. D. Beresford as "one of the greatest novels in the world".[55] While Glen Cavaliero describes it "as Powys's most enthralling novel" despite "all its many and glaring faults".[56]

In a review of the 1955 reprint, Roland Mathias describes Powys "as a strangely limited writer, fecund but narrow in his fecundity".[57] He suggests that Powys "may not be a novelist at all, or less one than historian, philosopher and image-maker".[58] Mathias finds Powys's characters unsatisfying: "It is, unfortunately, the plot that moves, not the characters. With few exceptions they do not develop".[59] But, he notes,

- It is not given to one writer in a generation to enjoy so embracing an imagination and to simulate life and beyond-life, to gather in preposterous and tender, and to go on being so interesting in himself that his fictions hardly matter.[60]

However, though Jeremy Hooker sees all the major characters, as "reflections of a dominant psychological bias in the author", he argues that "Powys is, supremely, a master of personalities–of massive,self-consistent personalities. ... Evans is his creator's mouthpiece, but his ideas are consistent with his character".[61]

A Glastonbury Romance was translated into French by Jean Queval, as Les enchantements de Glastonbury and published in 1975/6 (in four volumes) by Gallimard in their "Collection Du monde entier," with a preface by Catherine Lépront.[62] In the German-speaking world, admirers included Hermann Hesse, Alfred Andersch, Hans Henny Jahnn, Karl Kerényi and Elias Canetti.[63] It was published in Germany by Verlag Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main, 2000, ISBN 3-86150-258-5; (Munich: Hanser, 1998).

Notes[]

- ^ Powys's first novel Wood and Stone (1915) was dedicated to Thomas Hardy. See also Autobiography (1967), pp. 224–25, 227, 229–30, etc.

References[]

- ^ H. P. Collins, John Cowper Powys: Old Earth-Man. London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1966, p.78.

- ^ "Northwold". www.literarynorfolk.co.uk.

- ^ Jeremy Hooker, John Cowper Powys. University of Wales Press, 1973, p. 44.

- ^ a b Drabble, Margaret (11 August 2006). "The English degenerate". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Powys 1955, p. xiii.

- ^ John Cowper Powys, Glastonbury: 'Author's Review', 1932 ". The Powys Review, no. 9, vol. 3i, (1981–82), p. 8

- ^ "William Cowper Johnson (1813-1893)". oldshirburnian.org.uk. 23 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Services & Pilgrimage". Glastonbury Abbey. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Conservation Area Appraisal Glastonbury" (PDF). Mendip District Council. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ Keith 2010, p. 76.

- ^ Keith 2010, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Krissdóttir2007, pp. 252–53.

- ^ P.J. Kavanagh, "J.C. Powys–A Glastonbury Romance<". Theology, January 1977, p. 12.

- ^ Kenneth Hopkins, The Powys Brothers. Southrepps, Norfolk: Warren House Press, 1972, p. 157.

- ^ Allcroft, Arthur Hadrian (1908), Earthwork of England: Prehistoric, Roman, Saxon, Danish, Norman and Mediæval, Nabu Press, pp. 69–70, ISBN 978-1-178-13643-2, retrieved 12 April 2011

- ^ "Two Accounts of the Exhumation of Arthur's Body: Gerald of Wales". britannia.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "Definition of Holy Grail". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Campbell 1990, p. 210.

- ^ "Myths & Legends | Explore | Glastonbury Abbey". www.glastonburyabbey.com.

- ^ Brown, Arthur C. L. (2 December 2020). "The Bleeding Lance". PMLA. 25 (1): 6. doi:10.2307/456810. ISSN 0030-8129. JSTOR 456810.

- ^ Lacy & Wilhelm 2013.

- ^ Thorpe 1966, but see also Loomis 1956

- ^ See Padel 1994; Sims-Williams 1991; Green 2007b; and Roberts 1991a

- ^ ”JCP and Merlin”, W. J. Keith, ‘’A Glastonbury Romance Revisited’’. The Powys Society, 2019, p. 115.

- ^ Glen Cavaliero, John Cowper Powys: Novelist. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973, p.65. H. P. Collins describes Geard, as "inescapably Merlin redivivus ". John Cowper Powys: Old Earth Man. London: Barrie and Rockcliff, 1966, p. 78.

- ^ John Cowper Powys in Search of a Landscape. Totowa, NJ: Barnes and Noble, 1982, pp. 115-16.

- ^ (1934) London: Macdonald, 1967, p.24

- ^ London: Macdonald, 1961, pp. 233, 238.

- ^ John Cowper Powys, Glastonbury: 'Author's Review', 1932 ". The Powys Review, no. 9, vol. 3i, (1981–82), p. 7

- ^ Janina Nordius, "I'm Myself Alone": Solitude and Transcendence in John Cowper Powys. Göteborg, Sweden: University of Gothenburg, p.73

- ^ Coates, p. 92.

- ^ Cavaliero, p. 74

- ^ Neglected Powers. London: Routtledge & Kegan Paul,p. 178.

- ^ The Powys Brothers, p. 158.

- ^ Keith 2010, pp. 158–64.

- ^ Powys 1955, p. 124.

- ^ "Montacute", British History Online

- ^ "The Powys Family". Dorset Pages. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ The Mabinogion, translated by Lady Charlotte Guest (1906). J. M. Dent: London, 1927, p. 310.

- ^ Powys 1955, p. 800.

- ^ See also Cavaliero, Glen. John Cowper Powys, Novelist. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973, p. 63

- ^ Krissdóttir 2007, p. 256.

- ^ "Grail Messenger", Keith, W. J. "John Cowper, Powys’s A Glastonbury Romance: A Reader’s Companion", p. 25

- ^ Francis Berry, "J. C. Powys and Romance". Essays on John Cowper Powys, ed. Belinda Humfrey. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1972, p. 180.

- ^ Autobiography (1934). London: Macdonald, 1967, p. 66.

- ^ "Essay on Romance", Prose Works volume vi, p. 129, quoted in "Introduction" to Walter Scott's Quentin Durward, ed. Susan Maning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. xxv.

- ^ Margaret Anne Doody. The True Story of the Novel (1996). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997, p. 15.

- ^ David Punter, The Gothic, London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, p. 178.

- ^ G. Wilson Knight quoting Powys: "that there is nothing in the universe devoid of some mysterious element of consciousness ... whether animal, vegetable or mineral". Neglected Powers. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971, p. 399.

- ^ John Cowper Powys, Glastonbury: 'Author's Review', 1932". The Powys Review, no. 9, vol. 3i, (1981–82), p. 8.

- ^ W. J. Keith, A Glastonbury Romance Revisited, pp.32–33.

- ^ See John Cowper Powys, "Glastonbury: 'Author's Review' ", 1932 ", p.7.

- ^ Krissdóttir 2007, pp. 301–02, 304–07, 320.

- ^ Krissdóttir 2007, pp. 307–08.

- ^ "Hotch-Potch Genius: John Cowper Powys". The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1935, p. 6.

- ^ Cavaliero 1973, p. 60.

- ^ "Glad-Y-Haf". Dock Leaves. A John Cowper Powys Number. Spring, 1956, pp.20-29.

- ^ "Glad-Y-Haf", Dock Leaves', p,28

- ^ "Glad-Y-Haf", Dock Leaves, p.22.

- ^ "Glad-Y-Haf", Dock Leaves, p.28.

- ^ John Cowper Powys Writers of Wales series. University of Wales, Press,1973, p.52.

- ^ "Les enchantements de Glastonbury - Biblos - GALLIMARD - Site Gallimard". www.gallimard.fr.

- ^ "Afterword" by Elmar Schenkel to the German translation Carl Hanser Verlag, München 1995, ISBN 978-3-446-18276-9. p. 1229.

Works cited[]

- Cavaliero, Glen (1973). John Cowper Powys: Novelist. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-812049-0.

- Keith, W. J. (April 2010). A Glastonbury Romance Revisited. Powys Society. ISBN 978-1-874559-38-2.

- Krissdóttir, Morine (6 September 2007). Descents of Memory: A Life of John Cowper Powys. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-58567-917-1.

- Lacy, Norris J.; Wilhelm, James J. (2013). The Romance of Arthur: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-78288-3.

- Powys, John Cowper (1955). A Glastonbury Romance. Macdonald.

Further reading[]

Keith, W. J. "John Cowper, Powys’s A Glastonbury Romance: A Reader’s Companion"

External links[]

- Modernist novels

- 1932 British novels

- Modern Arthurian fiction

- Anglo-Welsh novels

- Works by John Cowper Powys

- Novels set in Somerset