Adverse childhood experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) encompass various forms of physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction experienced in childhood. ACEs have been linked to premature death as well as to various health conditions, including those of mental disorders.[1][2] Resulting toxic stress has also been linked to childhood maltreatment, which is related to a number of neurological changes in the structure of the brain and its function. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study was the first large scale study to look at the relationship between ten categories of adversity in childhood and health outcomes in adulthood.[3]

Long term effects of ACEs[]

According to the Center for Youth Wellness website, "Exposure without a positive buffer, such as a nurturing parent or caregiver, can lead to a Toxic Stress Response in children, which can, in turn, lead to health problems like asthma, poor growth and frequent infections, as well as learning difficulties and behavioral issues. In the long term, exposure to ACEs can also lead to serious health conditions like heart disease, stroke, and cancer later in life."[4]

Adverse childhood experiences are equal to various stresses, and a serious adversity is defined as a trauma.[5] The World Health Organization (WHO) recognises that prolonged stress in childhood can have life-long implications for the development of many diseases. Moreover ACEs can disrupt early brain development leading to the possible development of several disorders. WHO has designed a screening questionnaire to be used internationally in order to list adverse effects, and relate them to future developments in the hope of possible preventive interventions. The questionnaire is titled the Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ).[6]

Neurobiology of stress[]

Cognitive and neuroscience researchers have examined possible mechanisms that might explain the negative consequences of adverse childhood experiences on adult health.[7] Adverse childhood experiences can alter the structural development of neural networks and the biochemistry of neuroendocrine systems[8][9][10][11] and may have long-term effects on the body, including speeding up the processes of disease and aging and compromising immune systems.[12][13][14]

Allostatic load refers to the adaptive processes that maintain homeostasis during times of toxic stress through the production of mediators such as adrenaline, cortisol and other chemical messengers. According to researcher Bruce S. McEwen, who coined the term:

These mediators of the stress response promote adaptation in the aftermath of acute stress, but they also contribute to allostatic overload, the wear and tear on the body and brain that result from being 'stressed out.' This conceptual framework has created a need to know how to improve the efficiency of the adaptive response to stressors while minimizing overactivity of the same systems, since such overactivity results in many of the common diseases of modern life. This framework has also helped to demystify the biology of stress by emphasizing the protective as well as the damaging effects of the body's attempts to cope with the challenges known as stressors.[15]

Additionally, epigenetic transmission may occur due to stress during pregnancy or during interactions between mother and newborns. Maternal stress, depression, and exposure to partner violence have all been shown to have epigenetic effects on infants.[11]

Implementing practices[]

As knowledge about the prevalence and consequences of adverse childhood experiences increases, trauma-informed and resilience-building practices based on the research is being implemented in communities, education, public health departments, social services, faith-based organizations and criminal justice. A few states are considering legislation.

Communities[]

As knowledge about the prevalence and consequences of ACEs increases, more communities seek to integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices into their agencies and systems. Research with American Indian tribal communities has demonstrated that social support and cultural involvement can ameliorate the effects of ACEs.[16] Additionally, focus group research with over 100 low-income urban youth indicates that the common systems of classifying ACEs are not currently sufficient in capturing community stressors, such as racial discrimination, poverty, and community violence, that can also result in childhood trauma.[17]

Qualitative studies have proposed a handful of models on how best to disseminate information about ACEs to community members in order to create trauma-informed systemic change. For example, after conducting a series of interviews and focus groups in 10 cities around the US, Ellis & Dietz (2017)[18] proposed the Building Community Resilience model, a two-phase model that emphasizes collaboration across public sectors in order to create a coordinated array of community services. The focus of phase 1 is developing shared goals and understanding between different stakeholders (community health workers, pediatricians, parents, etc) in order to assess areas of strength, design interventions, and create a broader network of care. Phase 2 then utilizes the established community care network to create coordinated initiatives aimed at prevention of toxic stress. Data collection and community feedback is to be conducted continuously in order to refine strategies. The empower action model (created as part of the South Carolina ACE Initiative)[19] also recommends a collaborative approach to knit together different community stakeholders and uses data-driven feedback to inform decision-making. The authors created concrete steps for implementation after studying the shortcomings of previous models and examining 3 years of post-ACE training survey data, then refining the model through a series of focus groups with participants who work in child welfare. In the empower action model, community resilience is built by reinforcing 5 protective factors across multiple social levels (individual, organizational, community, and public policy) and throughout the lifespan. Racial equity is fundamental for creating healthy communities, and in this model, ACE prevalence is expected to diminish as systemic barriers are removed for entire populations. Currently, 3 different state-funded agencies have implemented the empower action model and from these experiences the authors recommended the following: having representation from multiple stakeholders, selecting a facilitator for meetings, developing a formalized “readiness process” prior to application of the model, celebrating progress, and understanding that sustainable change takes time and flexibility.[20]

There is a paucity of empirical research documenting the experiences of communities who have attempted to implement information about ACEs and trauma-informed practice into widespread public action. The Matlin et al. (2019)[21] article on Pottstown, Pennsylvania’s process demonstrated the challenges associated with community implementation. The Pottstown Trauma-Informed Community Connection (PTICC) initiative evolved from a series of prior collectives that all had similar goals of creating community resilience in order to prevent and treat ACEs. Over the course of the two year study, over 230 individuals from nearly 100 organizations attended one training offered by the PTICC, raising the number of engaged public sectors from 2 to 14. Participation in training and events was fairly steady and this was largely due to community networking.

However, the PTICC faced several challenges similar to those predicted by the Building Community Resilience model. These barriers included availability of resources over time, competition for power within the group, and the lack of systemic change needed to support long-term goals. Still, Pottstown has built a trauma-informed community foundation and offers lessons to other communities who have similar goals: start with a dedicated small team, identify community connectors, secure long term financial backing, and conduct data-informed evaluations throughout.[22]

Other community examples exist, such as Tarpon Springs, Florida which became the first trauma-informed community in 2011.[23][24] Trauma-informed initiatives in Tarpon Springs include trauma-awareness training for the local housing authority, changes in programs for ex-offenders, and new approaches to educating students with learning difficulties.[25]

Education[]

ACEs exposure is widespread in the US, one study from the National Survey of Children's Health reported that approximately 68% of children 0–17 years old had experienced one or more ACEs.[26] The impact of ACEs on children can manifest in difficulties focusing, self regulating, trusting others, and can lead to negative cognitive effects. One study found that a child with 4 or more ACEs was 32 times more likely to be labeled with a behavioral or cognitive problem than a child with no ACEs.[27] Another study by the Area Health Education Center of Washington State University found that students with at least three ACEs are three times as likely to experience academic failure, six times as likely to have behavioral problems, and five times as likely to have attendance problems.[28] The trauma-informed school movement aims to train teachers and staff to help children self-regulate, and to help families that are having problems that result in children's normal response to trauma. It also seeks to provide behavioral consequences that will not re-traumatize a child.[29]

Trauma-informed education refers to the specific use of knowledge about trauma and its expression to modify support for children to improve their developmental success.[30] The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) describes a trauma-informed school system as a place where school community members work to provide trauma awareness, knowledge and skills to respond to potentially negative outcomes following traumatic stress.[31] The NCTSN published a study that discussed the ARC (attachment, regulation and competency) model, which other researchers have based their subsequent studies of trauma-informed education practices off of.[27][32] Trauma-sensitive or trauma-informed schooling has become increasingly popular in Washington, Massachusetts, and California in the last 10 years.[26]

One study details how several San Francisco schools provided trauma-informed support based on the ARC model to students, adults in the system, and the school system as a whole through universal learning strategies, plans and techniques for children with trauma, and by providing trauma-informed therapy to those children.[32] At El Dorado, an elementary school in this study in San Francisco, trauma-informed practices were associated with a suspension reduction of 89%.[33]

Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, Washington, adapted a trauma-informed approached to discipline and reduced its suspensions by 85%.[34] Rather than standard punishment, students are taught to recognize their reaction to stress and learn to control it. Spokane, Washington, schools conducted a research study that demonstrated that academic risk was correlated with students’ experiences of traumatic events known to their teachers.[28][35] The same school district has begun a study to test the impact of trauma-informed intervention programs, in an attempt to reduce the impact of toxic stress.

In Brockton, Massachusetts, a community-wide meeting led to a trauma-informed approach being adopted by the Brockton School District.[29] So far, all of the district's elementary schools have implemented trauma-informed improvement plans, and there are plans to do the same in the middle school and high school. About one-fifth of the district teachers have participated in a course on teaching traumatized students. Police alert schools when they have arrested someone or visited at a student's address. Massachusetts state legislation has sought to require all schools to develop plans to create "safe and supportive schools".[29]

Social services[]

Social service providers—including welfare systems, housing authorities, homeless shelters, and domestic violence centers – are adopting trauma-informed approaches that help to prevent ACEs or minimize their impact. Utilizing tools that screen for trauma can help a social service worker direct their clients to interventions that meet their specific needs.[36] Trauma-informed practices can also help social service providers look at how trauma impacts the whole family.[37]

Trauma-informed approaches can improve child welfare services by 1) openly discussing trauma and 2) addressing parental trauma.[according to whom?][38] The New Hampshire Division for Children Youth and Families (DCYF) is taking a trauma-informed approach to their foster care services by educating staff about childhood trauma, screening children entering foster care for trauma, using trauma-informed language to mitigate further traumatization, mentoring birth parents and involving them in collaborative parenting, and training foster parents to be trauma-informed.[36]

In Albany, New York the HEARTS Initiative has led to local organizations developing trauma-informed practice.[38] Senior Hope Inc., an organization serving adults over the age of 50, began implementing the 10-question ACE survey and talking with their clients about childhood trauma. The LaSalle School, which serves orphaned and abandoned boys, began looking at delinquent boys in from a trauma-informed perspective and began administering the ACE questionnaire to their clients.

Housing authorities are also becoming trauma-informed. Supportive housing can sometimes recreate control and power dynamics associated with clients’ early trauma.[39] This can be reduced through trauma-informed practices, such as training staff to be respectful of clients' space by scheduling appointments and not letting themselves into clients' private spaces, and also understanding that an aggressive response may be trauma-related coping strategies.[39] The housing authority in Tarpon Springs provided trauma-awareness training to staff so they could better understand and react to their clients' stress and anger resulting from poor employment, health, and housing.[25]

A survey of 200 homeless individuals in California and New York demonstrated that more than 50% had experienced at least four ACEs.[40] In Petaluma, California, the Committee on the Shelterless (COTS) uses a trauma-informed approach called Restorative Integral Support (RIS) to reduce intergenerational homelessness.[41] RIS increases awareness of and knowledge about ACEs, and calls on staff to be compassionate and focus on the whole person. COTS now consider themselves ACE-informed and focus on resiliency and recovery.

Health care services[]

Screening for or talking about ACEs with parents and children can help to foster healthy physical and psychological development and can help doctors understand the circumstances that children and their parents are facing. By screening for ACEs in children, pediatric doctors and nurses can better understand behavioral problems. Some doctors have questioned whether some behaviors resulting in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses are in fact reactions to trauma. Children who have experienced four or more ACEs are three times as likely to take ADHD medication when compared with children with less than four ACEs.[42] Screening parents for their ACEs allows doctors to provide the appropriate support to parents who have experienced trauma, helping them to build resilience, foster attachment with their children, and prevent a family cycle of ACEs.[43][44] Trauma-informed pediatric care also allows doctors to develop a more trusting relationship with parents, opening the lines of communication.[45] At Montefiore Medical Center ACEs screenings will soon be implemented in 22 pediatric clinics. In a pilot program, any child with one parent who has an ACE score of four or higher is offered enrollment and receive a variety of services. For families enrolled in the program parents report fewer ER visits and children have healthier emotional and social development, compared with those not enrolled.[43][46]

Public health[]

Most American doctors as of 2015 do not use ACE surveys to assess patients. Objections to doing so include that there are no randomized controlled trials that show that such surveys can be used to actually improve health outcomes, there are no standard protocols for how to use the information gathered, and that revisiting negative childhood experiences could be emotionally traumatic.[47] Other obstacles to adoption include that the technique is not taught in medical schools, is not billable, and the nature of the conversation makes some doctors personally uncomfortable.[47]

Some public health centers see ACEs as an important way (especially for mothers and children)[48] to target health interventions for individuals during sensitive periods of development early in their life, or even in utero.[48] For example, Jefferson Country Public Health clinic in Port Townsend, Washington, now screens pregnant women, their partners, parents of children with special needs, and parents involved with CPS for ACEs.[49] With regard to patient counseling, the clinic treats ACEs like other health risks such as smoking or alcohol consumption.

Psychologists, politicians, therapists, educators, and countless[vague] other professionals interested in advocating for universal screening for ACEs while creating awareness of ACEs and possible treatments for their residual effects has resulted in the launching of a public health campaign Stress Health Public Education Campaign to bring greater attention to the problems implicated by stress and toxic stress in childhood.[50][51][unreliable source?]

Resilience and Resources[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Resilience is not a trait that people either have or do not have. It involves behaviors, thoughts and actions that can be learned and developed in anyone. According to the American Psychological Association (2017), resilience is the ability to adapt in the face of adversity, tragedy, threats or significant stress — such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems or workplace and financial stressors. Resilience refers to bouncing back from difficult experiences in life. There is nothing extraordinary about resilience. People often demonstrate resilience in times of adversity. However, being resilient does not mean that a person will not experience difficulty or distress, as emotional pain is common for people when they suffer from a major adversity or trauma. In fact, the path to resilience often involves considerable emotional pain [70].

Resilience and access to other resources are protective factors.[16][52][53] Having resilience can benefit children who have been exposed to trauma and have a higher ACE score. Children who can learn to develop it, can use resilience to build themselves up after trauma. A child who has not developed resilience will have a harder time coping with the challenges that can come in adult life. People and children who are resilient, embrace the thinking that adverse experiences do not define who they are. They also can think about past events in their lives that were traumatic, and, try to reframe them in a way that is constructive. They are able to find strength in their struggle and ultimately can overcome the challenges and adversity that was faced in childhood.[54] In childhood, resiliency can come from having a caring adult in a child's life. Resiliency can also come from having meaningful moments such as an academic achievement or getting praise from teachers or mentors. In adulthood, resilience is the concept of self-care. If you are taking care of yourself and taking the necessary time to reflect and build on your experiences, then you will have a higher capacity for taking care of others. Adults can also use this skill to counteract some of the trauma they have experienced. Self-care can mean a variety of things. One example of self-care, is knowing when you are beginning to feel burned out and then taking a step back to rest and recuperate yourself. Another component of self-care is practicing mindfulness or engaging in some form of prayer or meditation. If you are able to take the time to reflect upon your experiences, then you will be able to build a greater level of resiliency moving forward. All of these strategies put together can help to build resilience and counteract some of the childhood trauma that was experienced. With these strategies children can begin to heal after experiencing adverse childhood experiences. This aspect of resiliency is so important because it enables people to find hope in their traumatic past. When first looking at the ACE study and the different correlations that come with having 4 or more traumas, it is easy to feel defeated. It is even possible for this information to encourage people to have unhealthy coping behaviors. Introducing resilience and the data that supports its positive outcome in regards to trauma, allows for a light at the end of a tunnel. It gives people the opportunity to be proactive instead of reactive when it comes to addressing the traumas in their past.

Criminal justice[]

Since research on decarceration in the United States suggests that incarcerated individuals are much more likely to have been exposed to violence and suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),[55] a trauma-informed approach may better help to address some of these criminogenic risk factors and can create a less traumatizing criminal justice experience.[according to whom?] Programs, like Seeking Safety, are often used to help individuals in the criminal justice system learn how to better cope with trauma, PTSD, and substance abuse.[56] Juvenile courts better help deter children from crime and delinquency when they understand the trauma many of these children have experienced.[57] The criminal justice system itself can also retraumatize individuals.[58] This can be prevented by creating safer facilities where correctional and police officers are properly trained to keep incidents from escalating.[55] Partnerships between police and mental health providers can also reduce the possible traumatizing effects of police intervention and help provide families with the proper mental health and social services.[59] The Women's Community Correctional Center of Hawaii began a Trauma-Informed Care Initiative that aims to train all employees to be aware and sensitive to trauma, to screen all women in their facility for trauma, to assess those who have experienced trauma, and begin providing trauma-informed mental health care to those women identified.[58]

Legislation[]

Vermont has passed a bill, Act 43(H.508), an act relating to building resilience for individuals experiencing adverse childhood experiences which acknowledges the life span effects of ACEs on health outcomes, seeks wide use of ACE screening by health providers and aims to educate medical and health school students about ACEs.[60][61][62] Previously Washington State passed legislation to set up a public-private partnership to further community development of trauma-informed and resilience-building practices that had begun in that state; but it was not adequately funded.[citation needed] On August 18, 2014, California lawmakers unanimously passed ACR No. 155, which encourages policies reducing children's exposure to adverse experiences.[63] Recent Massachusetts legislation supports a trauma-informed school movement as part of The Reduction of Gun Violence bill (No. 4376). This bill aims to create "safe and supportive schools" through services and initiatives focused on physical, social, and emotional safety.[64]

ACEs score[]

To determine someone's ACEs score, they answer the 10 Adverse Childhood Experiences questions relating to events prior to their eighteenth birthday.[65] The questions are:

- 1. Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often... Swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you? or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?

- 2. Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often... Push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? or Ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

- 3. Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever... Touch or fondle you or have you touch their body in a sexual way? or Attempt or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with you?

- 4. Did you often or very often feel that ... No one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? or Your family didn't look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?

- 5. Did you often or very often feel that ... You didn't have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you? or Your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?

- 6. Were your parents ever separated or divorced?

- 7. Was your parent or caretaker: Often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at her? or Sometimes, often, or very often kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, or hit with something hard? or Ever repeatedly hit over at least a few minutes or threatened with a gun or knife?

- 8. Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic, or who used street drugs?

- 9. Was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide?

- 10. Did a household member go to prison?

Adverse Childhood Experiences movement[]

The Adverse Childhood Experiences movement is an initiative to revolutionize national awareness, and understanding of the health impacts of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and toxic stress, and to implement programs and protocols to prevent, recognize, and address them when they have occurred.[1] Adverse childhood experiences are defined as potentially traumatic experiences that can occur between the ages of 0 and 17.[1] The movement is being driven by pediatric clinicians, educators, parents, policymakers and other child-serving professionals and advocates who are working to implement universal screening for adverse childhood experiences.[1]

Start of the ACE-aware movement[]

The ACE aware movement arose out of the need for a bidirectional effort to create a public health change, with both individuals and institutions/ government systems.[66] Change on the individual level is essential, because individual change is self-directed.[1] The institutions and government systems engagement is essential, because without the structure surrounding individuals changing, the very systems that are intended to help, can perpetuate the cycle of trauma.

International adoption of the ACEs model[]

The U.S. ACEs list was created in 1997 when a study was conducted to examine different childhood traumas. From 1995-1997, the CDC Kaiser ACE study involved more than 17,000 people sharing their stories about their unforgettable childhood trauma experiences. They used this study to make a list of ACEs to determine and examine how these traumatizing experiences can lead to health issues and stunt developmental growth. ACEs are divided into three categories: abuse, household challenges, and neglect. Examples of ACEs include being exposed to abuse and neglect, violence in the family, mental illness, parental divorce or substance abuse. It is said to disrupt a child's development, leading to poor health outcomes and low life expectancy.[67]

In the UK in 2017 a study was made based on the original US study and presented together with recommendations for early intervention to the UK parliament.[68]

The World Health Organization has designed a far more extensive screening questionnaire than the original US version, designed to be used internationally in order to relate adverse conditions to future developments in the hope of possible preventive interventions. In addition to the ACEs identified in the US questionnaire it includes questions related to such adverse experiences as warfare. The questionnaire is titled the Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ).[6]

Adverse Childhood Experiences Study[]

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) is a research study conducted by the U.S. health maintenance organization Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[69] that was originally published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.[70] Participants were recruited to the study between 1995 and 1997 and have since been in long-term follow up for health outcomes. The study has demonstrated an association of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) with health and social problems across the lifespan. The study has produced many scientific articles and conference and workshop presentations that examine ACEs.[69][70]

In the 1980s, the dropout rate of participants at Kaiser Permanente's obesity clinic in San Diego, California, was about 50%; despite all of the dropouts successfully losing weight under the program.[71] Vincent Felitti, head of Kaiser Permanente's Department of Preventive Medicine in San Diego, conducted interviews with people who had left the program, and discovered that a majority of 286 people he interviewed had experienced childhood sexual abuse. The interview findings suggested to Felitti that weight gain might be a coping mechanism for depression, anxiety, and fear.[71]

Felitti and Robert Anda from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) went on to survey childhood trauma experiences of over 17,000 Kaiser Permanente patient volunteers.[71] The 17,337 participants were volunteers from approximately 26,000 consecutive Kaiser Permanente members. About half were female; 74.8% were white; the average age was 57; 75.2% had attended college; all had jobs and good health care, because they were members of the Kaiser health maintenance organization.[72] Participants were asked about different types of adverse childhood experiences that had been identified in earlier research literature:[73]

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Physical neglect

- Emotional neglect

- Exposure to domestic violence

- Household substance abuse

- Household mental illness

- Parental separation or divorce

- Incarcerated household member

Findings[]

According to the United States' Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the ACE study found that:

- Adverse childhood experiences are common. For example, 28% of study participants reported physical abuse and 21% reported sexual abuse. Many also reported experiencing a divorce or parental separation, or having a parent with a mental and/or substance use disorder.[76]

- Adverse childhood experiences often occur together. Almost 40% of the original sample reported two or more ACEs and 12.5% experienced four or more. Because ACEs occur in clusters, many subsequent studies have examined the cumulative effects of ACEs rather than the individual effects of each.[76]

- Adverse childhood experiences have a dose–response relationship with many health problems. As researchers followed participants over time, they discovered that a person's cumulative ACEs score has a strong, graded relationship to numerous health, social, and behavioral problems throughout their lifespan, including substance use disorders. Furthermore, many problems related to ACEs tend to be comorbid, or co-occurring.[76]

About two-thirds of individuals reported at least one adverse childhood experience; 87% of individuals who reported one ACE reported at least one additional ACE.[73] The number of ACEs was strongly associated with adulthood high-risk health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, promiscuity, and severe obesity, and correlated with ill-health including depression, heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease and shortened lifespan.[73][77] [78] Compared to an ACE score of zero, having four adverse childhood experiences was associated with a seven-fold (700%) increase in alcoholism, a doubling of risk of being diagnosed with cancer, and a four-fold increase in emphysema; an ACE score above six was associated with a 30-fold (3000%) increase in attempted suicide.

The ACE study's results suggest that maltreatment and household dysfunction in childhood contribute to health problems decades later. These include chronic diseases—such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes—that are the most common causes of death and disability in the United States.[79] The study's findings, while relating to a specific population within the United States, might reasonably be assumed to reflect similar trends in other parts of the world, according to the World Health Organization.[79]

Subsequent surveys[]

The ACE Study has produced more than 50 articles that look at the prevalence and consequences of ACEs.[80][non-primary source needed] It has been influential in several areas. Subsequent studies have confirmed the high frequency of adverse childhood experiences, or found even higher incidences in urban or youth populations.

The original study questions have been used to develop a 10-item screening questionnaire.[81][82] Numerous subsequent surveys have confirmed that adverse childhood experiences are frequent.

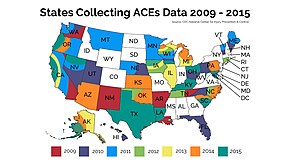

The CDC runs the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS),[83] an annual survey conducted by individual state health departments in all 50 states. An expanded survey instrument in several states found each state to be similar.[81] Some states have collected additional local data.[84][85] Adverse childhood experiences were even more frequent in studies in urban Philadelphia[86] and in a survey of young mothers (mostly younger than 19).[87] Internationally, an Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) is undergoing validation testing.[88] Surveys of adverse childhood experiences have been conducted in Romania,[89] the Czech Republic,[90] the Republic of Macedonia,[91] Norway, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, Canada, China and Jordan.[75][not specific enough to verify] Child Trends used data from the 2011/12 National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH) to analyze ACEs prevalence in children nationally, and by state. The NSCH's list of "adverse family experiences" includes a measure of economic hardship and shows that this is the most common ACE reported nationally.[92]

Additional Information[]

Sandra Bloom and Brian Farragher's book Destroying Sanctuary states in its introduction that 17th century philosophers like Descartes took apart the person and "turned over the body to physicians and the mind to philosophers and clergy," and in the ACEs movement society is now trying to bring them back together.[3]

ACE Nashville has repurposed the acronym, ACE to stand for All Children Excel and is trying to raise awareness about adverse childhood experiences in Nashville, Tennessee.[67]

See also[]

- Alcoholism in family systems

- Child abuse

- Childhood trauma

- Decarceration in the United States

- Early childhood trauma

- Effects of domestic violence on children

- Pedophilia

- Social determinants of health

- Verbal abuse

- Weathering hypothesis

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "About Adverse Childhood Experiences |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- ^ "What Are ACEs? And How Do They Relate to Toxic Stress?". Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bloom, Sandra L.; Farragher, Brian (2010-10-28). Destroying Sanctuary: The Crisis in Human Service Delivery Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199830848.

- ^ "How ACEs Affect Health". Center for Youth Wellness. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- ^ Pearce, J; Murray, C; Larkin, W (July 2019). "Childhood adversity and trauma: experiences of professionals trained to routinely enquire about childhood adversity". Heliyon. 5 (7): e01900. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01900. PMC 6658729. PMID 31372522.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "WHO | Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ)". WHO. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Weiss JS, Wagner SH (1998). "What explains the negative consequences of adverse childhood experiences on adult health? Insights from cognitive and neuroscience research (editorial)". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 14 (4): 356–360. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00011-7. PMID 9635084.

- ^ Anda RF; Felitti VJ; Bremner JD; et al. (April 2006). "The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 256 (3): 174–186. doi:10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. PMC 3232061. PMID 16311898.

- ^ Danese A; McEwen BS (April 12, 2012). "Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease". Physiology & Behavior. 106 (1): 29–39. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. PMID 21888923. S2CID 3840754.

- ^ Teicher, M.D., Martin H. "Windows of Vulnerability: Understanding how early stress alters trajectories of brain development and sets the stage for the emergence of mental disorders" (PDF). The Balanced Mind. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kolassa, Iris - Tatjana (2016). "Biological memory of childhood maltreatment – current knowledge and recommendations for future research" (PDF). Ulmer Volltextserver - Institutional Repository der Universität Ulm. doi:10.18725/OPARU-2420. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Sorrow, April (May 30, 2013). "Study uncovers cost of resiliency in kids". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Moffitt, Terrie E. (November 2013). The Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank. "Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: Clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces". Development and Psychopathology. 25 (4pt2): 1619–1634. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000801. PMC 3869039. PMID 24342859.

- ^ Rogosch FA; Dackis MN; Cicchetti D (November 2011). "Child maltreatment and allostatic load: consequences for physical and mental health in children from low-income families". Development and Psychopathology. 23 (4): 1107–24. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000587. PMC 3513367. PMID 22018084.

- ^ McEwen, Bruce S. (2005). "Stressed or stressed out: What is the difference?". Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 30 (5): 315–318. ISSN 1180-4882. PMC 1197275. PMID 16151535.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brockie, Teresa N.; Elm, Jessica H. L.; Walls, Melissa L. (2018-09-01). "Examining protective and buffering associations between sociocultural factors and adverse childhood experiences among American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes: a quantitative, community-based participatory research approach". BMJ Open. 8 (9): e022265. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022265. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 6150153. PMID 30232110.

- ^ Wade Jr., Roy; Shea, Judy A.; Rubin, David; Wood, Joanne (2014). "Adverse Childhood Experiences of Low Income Youth". Pediatrics. 134 (1): e13–e20. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2475. PMID 24935995. S2CID 17428799.

- ^ Ellis, Wendy R.; Dietz, William H. (2017). "A New Framework for Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences: The Building Community Resilience Model". Academic Pediatrics. 17 (7S): S93–S86. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011. PMID 28865665.

- ^ Srivastav, Aditi; Strompolis, Melissa; Moseley, Amy; Daniels, Kelsay (2020). "The Empower Action Model: A Framework for Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences by Promoting Health, Equity, and Well-Being Across the Life Span". Health Promotion Practice. 21 (4): 525–534. doi:10.1177/1524839919889355. PMC 7298349. PMID 31760809.

- ^ Srivastav, Aditi; Strompolis, Melissa; Moseley, Amy; Daniels, Kelsay (2020). "The Empower Action Model: A Framework for Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences by Promoting Health, Equity, and Well-Being Across the Life Span". Health Promotion Practice. 21 (4): 525–534. doi:10.1177/1524839919889355. PMC 7298349. PMID 31760809.

- ^ Maitlin, Samantha; Champine, Robey; Strambler, Michael; O'Brien, Caitlin; Hoffman, Erin; Whitson, Melissa; Kolka, Laurie; Kraemer Tebes, Jacob (2019). "A Community's Response to Adverse Childhood Experiences: Building a Resilient, Trauma‐Informed Community". American Journal of Community Psychology. 64 (3–4): 451–466. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12386. PMID 31486086.

- ^ Maitlin, Samantha; Champine, Robey; Strambler, Michael; O'Brien, Caitlin; Hoffman, Erin; Whitson, Melissa; Kolka, Laurie; Kraemer Tebes, Jacob (2019). "A Community's Response to Adverse Childhood Experiences: Building a Resilient, Trauma‐Informed Community". American Journal of Community Psychology. 64 (3–4): 451–466. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12386. PMID 31486086.

- ^ Stevens "Community Projects", ACEs Connection, 25 September 2012

- ^ Saenger "PEACE4TARPON Trauma Informed Community Initiative", 30 March 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens "Tarpon Springs, FL, may be first trauma-informed city in U.S.", ACEs Too High, 13 February 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blodgett, Cristopher; Lanigan, Jane D. (2018). "The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children". School Psychology Quarterly. 33 (1): 137–146. doi:10.1037/spq0000256. PMID 29629790. S2CID 4717363.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Plumb, J.L.; Bush, K.A.; Kersevich, S.E. (2016). "Trauma-Sensitive Schools: An Evidence Based Approach". School Social Work Journal. 40 (2): 37–60.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens "Spokane, WA, students’ trauma prompts search for solutions", ACEs Too High, 28 February 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stevens "Massachusetts, Washington State lead U.S. trauma-sensitive school movement", ACEs Too High, 31 May 2012

- ^ Blodgett, C. (2013). "A Review of Community Efforts to Mitigate and Prevent Adverse Childhood Experiences and Trauma" (PDF). Washington State University Health Education Center: Spokane, WA.

- ^ National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Schools Committee. (2017). "Creating, Supporting, and Sustaining Trauma-Informed Schools: A System Framework" (PDF). Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Dorado, J.S.; Martinez, M.; McArthur, L.E.; Leibovitz, T. (2016). "Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A Whole-School, Multi-Level, Prevention and Intervention Program for Creating Trauma-Informed Safe and Supportive Schools". School Mental Health. 8 (1): 163–176. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0. S2CID 146359339.

- ^ Stevens "San Francisco’s El Dorado Elementary uses trauma-informed & restorative practices; suspensions drop 89%", ACEs Too High, 28 January 2014

- ^ Stevens, Jane Ellen (April 13, 2012). "Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, WA, tries new approach to school discipline — suspensions drop 85%". ACEs Too High!. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Stevens "There’s no such thing as a bad kid in these Spokane, WA, trauma-informed elementary schools", ACEs Too High, 20 August 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meister "Addressing Child Traumatic Stress in Child Welfare", Common Ground, July 2012

- ^ Family-Informed Trauma Treatment Center 15 July 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens "‘Starve the beast,’ say these cities – but don’t cut people off; reduce need for services instead", ACEs Too High, 30 July 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bebout "Waiting on the welcome mat: How to be at home with trauma-informed care" Archived 2016-01-27 at the Wayback Machine, camh Cross Currents, Winter 2010/2011

- ^ ACEs 360 "‘ACEs 360-New York" Archived 2014-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, ACEs 360 Iowa, Retrieved 15 July 2014

- ^ Larkin et al. "‘Mobilizing resilience and recovery in response to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among homeless people: A Restorative Integral Support (RIS) case study", Prevention Summit, Retrieved 15 July 2014

- ^ Ruiz "How Childhood Trauma Could Be Mistaken for ADHD", The Atlantic, 7 July 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens "To prevent childhood trauma, pediatricians screen children and their parents…and sometimes, just parents…for childhood trauma", ACEs Too High, 29 July 2014

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics "Promoting Children’s Health and Resiliency: A Strengthening Families Approach" Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, Center for the Study of Social Policy

- ^ Gottlieb "Toxic Stress and Trauma-Informed Pediatric Care" Archived 2014-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project

- ^ Montefiore Medical Group "Healthy Steps Program", Montefiore Medical Group

- ^ Jump up to: a b "10 Questions Some Doctors Are Afraid to Ask".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellerstedt "Adverse Childhood Experience: Public Health Surveillance Measures", Healthy Generations, Spring 2013

- ^ Stevens "Public health clinic adds child trauma to smoking, alcohol, HIV screening", ACEs Too High, 23 March 2012

- ^ "Building a Movement". Center for Youth Wellness. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- ^ "JOIN THE MOVEMENT". Stress Health. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Nurius, Paula S.; Green, Sara; Logan-Greene, Patricia; Borja, Sharon (July 2015). "Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: A stress process analysis". Child Abuse & Neglect. 45: 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008. ISSN 0145-2134. PMC 4470711. PMID 25846195.

- ^ Jones, Tiffany M.; Nurius, Paula; Song, Chiho; Fleming, Christopher M. (June 2018). "Modeling life course pathways from adverse childhood experiences to adult mental health". Child Abuse & Neglect. 80: 32–40. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.005. ISSN 0145-2134. PMC 5953821. PMID 29567455.

- ^ Elm, Jessica H. L.; Lewis, Jordan P.; Walters, Karina L.; Self, Jen M. (2016-06-02). "'I'm in this world for a reason': Resilience and recovery among American Indian and Alaska Native two-spirit women". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 20 (3–4): 352–371. doi:10.1080/10894160.2016.1152813. ISSN 1089-4160. PMC 6424359. PMID 27254761.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miller & Najavits "Creating trauma-informed correctional care: a balance of goals and environment", European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2012

- ^ Seeking Safety "Seeking Safety: A Model to Improve Coping Skills", Seeking Safety

- ^ Buffington et al. "Ten Things Every Juvenile Court Judge Should Know About Trauma and Delinquency", NCJFCJ, 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b National Association of State Mental Health Program Director "Creating A Place Of Healing and Forgiveness: The Trauma-Informed Care Initiative at the Women’s Community Correctional Center of Hawaii" Archived 2014-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, NASMHPD, 2013

- ^ The National Child Traumatic Stress Network "Creating A Trauma-Informed Law Enforcement System", NCTSN, April 2018

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-25. Retrieved 2017-10-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "No. 43. An act relating to building resilience for individuals experiencing adverse childhood experiences" (PDF). Vermont Legislature.

- ^ Prewitt "Vermont first state to propose bill to screen for ACEs in health care", ACEs Connection, 18 March 2014

- ^ Prewitt "CA Senate unanimously approves ACEs reduction resolution", ACEs Too High, 21 August 2014

- ^ Prewitt "Massachusetts "Safe and Supportive Schools" provisions signed into law, boosts trauma-informed school movement", ACEs Too High, 13 August 2014

- ^ Stevens, Jane (1 January 2017). "Got Your ACE, Resilience Scores?". acesconnection.com. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "ACE-Aware". ACE Aware Scotland. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Weight of Adverse Childhood Experiences". Nashville Scene. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Evidence-based early years intervention - Science and Technology Committee - House of Commons". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study". cdc.gov. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Felitti, Vincent J.; Anda, Robert F.; Nordenberg, Dale; Williamson, David F.; Spitz, Alison M.; Edwards, Valerie; Koss, Mary P.; Marks, James S. (1998). "Adverse Childhood Experiences". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 14 (4): 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. PMID 9635069.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stevens, Jane Ellen (8 October 2012). "The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study — the Largest Public Health Study You Never Heard Of". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "Prevalence of Individual Adverse Childhood Experiences". cdc.gov. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Anda RF; Felitti VJ (April 2003). "Origins and Essence of the Study" (PDF). ACE Reporter. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "The ACE Pyramid". Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Adverse Childhood Experiences". samhsa.gov. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Felitti, Vincent J; Anda, Robert F; et al. (May 1998). "Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 14 (4): 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. PMID 9635069.

- ^ Middlebrooks, J.S.; Audage, N.C. (2008). The Effects of Childhood Stress on Health Across the Lifespan (PDF). Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-05. Retrieved 2016-01-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b World Health Organization; International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (2006). Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence (PDF). Geneva, Switzerland. p. 12. ISBN 978-9241594363.

- ^ "Publications by Health Outcome". cdc.gov. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bynum, L.; et al. (December 17, 2010). "Adverse Childhood Experiences Reported by Adults — Five States, 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 59 (49): 1609–1613. PMID 21160456.

- ^ Anda, Robert (2007). "Finding Your ACE Score" (PDF). Acestudy.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2016.

- ^ Clinton Gudmunson; Lisa Ryherd; Karen Bougher; Jacy Downey; Meghan Gillette. Central Iowa ACEs Steering Committee (ed.). "Adverse Childhood Experiences in Iowa: A New Way of Understanding Lifelong Health: Findings From the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "ACEs 360 - New York". Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ "ACEs 360 - Arizona". Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ "The Philadelphia Urban ACE Study". 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Stevens, Jane Ellen (November 2, 2012). "Survey finds teen, young mothers using Crittenton services have alarmingly high ACE scores". ACEs Too High!. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Adriana Baban; Alina Cosma; Robert Balazsi; Dinesh Sethi; Victor Olsavszky (2013). "Survey of Adverse Childhood Experiences among Romanian university students" (PDF). World Health Organization. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Adverse childhood experiences survey among young people in the Czech Republic". World Health Organization. December 23, 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Marija Raleva; Dimitrinka Jordanova Peshevska; Dinesh Sethi (2013). "Survey of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Young People in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "Adverse Childhood Experiences: National and State-Level Prevalance" (PDF). Child Trends. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

Further reading[]

- Felitti, Vincent J. (2002). "The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead" (PDF). The Permanente Journal. 6 (1): 44–47. PMC 6220625. PMID 30313011.

External links[]

- CAPT: Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) via Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- Adverse Childhood Experiences Resources Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Adverse Childhood Experiences: Risk Factors for Substance Misuse and Mental Health Dr. Robert Anda, co-principal investigator, explains some of the study's basic findings (video)

- Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University (Environmental factors in child development)

- "Take The ACE Quiz – And Learn What It Does And Doesn't Mean", National Public Radio

- The ACE Score Acestudy.org

- ACE Global Research Network

- What is Your ACE Score?

- Adverse childhood experiences

- Child abuse

- Human development

- Child development

- Determinants of health

- Developmental psychology

- Initiatives

- Public health