Afghan National Army

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: collapse of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, following 2021 Taliban offensive. (August 2021) |

| Afghan National Army | |

|---|---|

Former emblem of the Afghan National Army | |

| Founded | c. 1722 1 December 2002 (as Afghan National Army) |

| Disbanded | 15 August 2021 (Fall of Kabul) |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Part of | |

| Motto(s) | “God, Country, Duty”[1][2][3] |

The Afghan National Army was[4] the land warfare branch of the Afghan Armed Forces. The Army’s roots could be traced back to the early 18th century when the Hotak dynasty was established in Kandahar followed by Ahmad Shah Durrani's rise to power. It was reorganized in 1880 during Emir Abdur Rahman Khan's reign.[5] Afghanistan remained neutral during the First and Second World Wars. From the 1960s to the early 1990s, the Afghan Army was equipped by the Soviet Union.[6]

Under the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the army was under the Ministry of Defense in Kabul and had been largely trained by US-led NATO forces. The 2004-2021 ‘Afghan National Army’ was divided into seven corps, with the 201st in Kabul, 203rd in Gardez, 205th in Kandahar, 207th in Herat, 209th in Mazar-i-Sharif, the 215th in Lashkargah, and the 217th in the north.

By 2014, most of Afghanistan came under government control with NATO playing a supporting role. However over the next few years the government slowly lost territory to the Taliban and eventually collapsed, with Kabul falling to the Taliban in 2021.[7][failed verification] The majority of training of the ANA was undertaken in the Afghan National Security University. In 2019, the ANA had approximately 180,000 soldiers out of an authorized strength of 195,000.[8] Despite its significant manpower on paper, in reality a significant portion of the Afghan National Army manpower were made up of ghost soldiers.[9][10]

Following the withdrawal of NATO supporting troops from Afghanistan in the Summer of 2021, in addition to a rapid offensive conducted by the Taliban, the Afghan National Army largely disintegrated.[11] This culminated in the fall of Kabul and President Ashraf Ghani fleeing the country to Dubai.[12] Large numbers of troops either abandoned their posts, negotiating surrenders,[13] in the face of the Taliban, with significant amounts of primarily US-made weapons and supplies being captured.[14]

Following the escape of President Ghani and the Fall of Kabul, the remaining forces of the ANA either deserted their posts or surrendered to the Taliban and the ANA de facto ceased to exist.[15] It has been reported that several remnants of the ANA have regrouped in Panjshir Valley, where they joined the anti-Taliban Panjshir resistance.[16] Around 500 - 600 remaining Afghan troops made up mostly of Afghan Comandos were reported to have refused to surrender to the Taliban in Kabul and instead joined up with US forces in the Hamid Karzai International Airport helping them secure the outer perimeter of the airport during the evacuation of Afganistan. According to Pentagon spokesman John Kirby the US will evacuate these remaining Afghan troops to safety if they wish to leave Afghanistan when the evacuation operation ends. [17]

History

The Royal Afghan Army

Historically, Afghans have served in the army of the Ghaznavids (963–1187), Ghurids (1148–1215), Delhi Sultanate (1206–1527), and the Mughals (1526–1858).[18] The Afghan National Army traces its origin to the early 18th century when the Hotak dynasty rose to power in Kandahar and defeated the Persian Safavid Empire at the Battle of Gulnabad in 1722.[19]

When Ahmad Shah Durrani formed the Durrani Empire in 1747, the Afghan Army fought a number of battles in the Punjab region of India during the 19th century. One of the famous battles was the 1761 Battle of Panipat in which the Afghan army decisively defeated the Hindu Maratha Empire.[20] The Afghans then fought with the Sikh Empire, until finally, the Sikh Marshal Hari Singh Nalwa died and Sikh conquests stopped. In 1839, the British successfully invaded Afghanistan and installed the exiled Shah Shujah Durrani into power. Their occupation of Afghanistan was challenged after Wazir Akbar Khan and his forces led an organized revolt against the occupying British. At the time, the Afghan Army was not an organized army, rather, Afghan tribal chiefs contributed fighting men when the Emir called upon their services.[21] The success of the uprising led to the 1842 retreat from Kabul where the Afghan army decimated British forces, thanks to effective use of the rugged terrain and weapons such as the Jezail.

At the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–80), Ali Ahmad Jalali cites sources saying that the regular army was about 50,000 strong and consisted of 62 infantry and 16 cavalry regiments, with 324 guns mostly organized in horse and mountain artillery batteries.[22] Sedra cites Jalali, who writes that '..although Amir Shir Ali Khan (1863–78) is widely credited for founding the modern Afghan Army, it was only under Abdur Rahman that it became a viable and effective institution.'[23] In 1880 Amir Abdur Rahman Khan established a newly equipped Afghan Army with help from the British. The Library of Congress Country Study for Afghanistan states:[5]

When [Abdur Rahman Khan] came to the throne, the army was virtually nonexistent. With the assistance of a liberal financial loan from the British, plus their aid in the form of weapons, ammunition, and other military supplies, he began a 20-year task of creating a respectable regular force by instituting measures that formed the long-term basis of the military system. These included increasing the equalization of military obligation by setting up a system known as the hasht nafari (whereby one man in every eight between the ages of 20 and 40 took his turn at military service); constructing an arsenal in Kabul to reduce dependence on foreign sources for small arms and other ordnance; introducing supervised training courses; organizing troops into divisions, brigades, and regiments, including battalions of artillery; developing pay schedules; and introducing an elementary (and harsh) disciplinary system.

Further improvements to the Army were made by King Amanullah Khan in the early 20th century just before the Third Anglo-Afghan War. King Amanullah fought against the British in 1919, resulting in Afghanistan becoming fully independent after the Treaty of Rawalpindi was signed. It appears from reports of Naib Sular Abdur Rahim's career that a Cavalry Division was in existence in the 1920s, with him being posted to the division in Herat Province in 1913 and Mazar-i-Sharif after 1927.[24] The Afghan Army was expanded during King Zahir Shah's reign, starting in 1933.

In 1953, Lieutenant General Mohammed Daoud, cousin of the King who had previously served as Minister of Defence, was transferred from command of the Central Corps in Kabul to become Prime Minister of Afghanistan.[25] Periodic border clashes with Pakistan seem to have taken place between 1950 and 1961.[26]

From 1949 to 1961, Afghanistan-Pakistan skirmishes took place along the frontier, culminating in fighting in Bajaur Agency in September 1960. This led to a breakoff in diplomatic relations between the two countries in September 1961.[27]

From the 1960s to the early 1990s, the Afghan Army received training and equipment mostly from the Soviet Union. In February – March 1957, the first group of Soviet military specialists (about 10, including interpreters) was sent to Kabul to train Afghan officers and non-commissioned officers.[28] At the time, there seems to have been significant Turkish influence in the Afghan Armed Forces, which waned quickly after the Soviet advisors arrived. By the late 1950s, Azimi describes three corps, each with a number of divisions, along the eastern border with Pakistan and several independent divisions.[29]

In the early 1970s, Soviet military assistance was increased. The number of Soviet military specialists increased from 1,500 in 1973 to 5,000 by April 1978.[30] The senior Soviet specialist at this time (from 29.11.1972 till 11.12.1975) was a Major General I.S. Bondarets (И.С. Бондарец), and from 1975 to 1978, the senior Soviet military adviser was Major General L.N. Gorelov. Before the 1978 Saur Revolution, according to military analyst George Jacobs, the Army included "some three armored divisions (570 medium tanks plus T 55s on order), eight infantry divisions (averaging 4,500 to 8,000 men each), two mountain infantry brigades, one artillery brigade, a guards regiment (for palace protection), three artillery regiments, two commando regiments, and a parachute kandak (battalion), which was largely grounded. All the formations were under the control of three corps level headquarters. All but three infantry divisions were facing Pakistan along a line from Bagram south to Khandahar."[31]

Socialist Afghanistan

On 27 April 1978 the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, Babrak Karmal and Amin overthrew the regime of Mohammad Daoud, who was killed the next day, along with most of his family.[32] The uprising was known as the Saur Revolution. On 1 May, Taraki became President, Prime Minister and General Secretary of the PDPA. The country was then renamed the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), and the PDPA regime lasted, in some form or another, until April 1992.

The strength of the army was greatly weakened during the early stages of PDPA rule. One of the main reasons for the small size was that the Soviet military were afraid the Afghan army would defect en masse to the enemy if total personnel increased. There were several sympathisers of the mujahideen within the military.[33] Even so, there were several elite units under the command of the Afghan army, for instance, the 26th Airborne Battalion, 444th, 37th and 38th Commando Brigades. The 26th Airborne Battalion proved politically unreliable, and in 1980 they initiated a rebellion against the PDPA government. The Commando Brigades were, in contrast, considered reliable and were used as mobile strike forces until they sustained excessive casualties. After sustaining these casualties the Commando Brigades were turned into battalions.[34]

Most soldiers were recruited for a three-year term, later extended to four-year terms in 1984.

The Afghan Army 1978[35]

- Central Corps (Kabul)

- (Kabul)

- (Kabul)

- 4th and 15th Armoured Brigades

- Republican Guard Brigade

- (Kandahar)

- 7th Armoured Brigade

- 15th Division (Kandahar)[36]

- (Gardez)

- (Chugha-Serai)

- 11th Division (Jalalabad)

- 12th Division (Gardez)

- 14th Division (Ghazni)

- (Herat)[37]

- 18th Division (Mazar-i-Sharif)

- 20th Division (Nahrin)

- 25th Division (Khost)

After the PDPA seizure of power, desertions swept the force, affecting the loyalty and moral values of soldiers. There were purges on patriotic junior and senior officers, and upper class Afghan aristocrats in society. On March 15, 1979, the Herat uprising broke out. The was detailed by the regime to put down the rebellion, but this proved a mistake, as there were few Khalqis in the division and instead it mutinied and joined the uprising.[38] Forces from Kabul had to be dispatched to suppress the rebellion.

Gradually the Army's three armoured divisions and now sixteen infantry divisions dropped in size to between battalion and regiment sized, with no formation stronger than about 5,000 troops.[39] It is not clear whether the three armoured formations were brigades or divisions: different authoritative sources give both designations. One of the first series of defections occurred in the , which, Urban wrote, defected by brigades in response to the Soviet intervention. It lost its 5th Brigade at Asmar in August 1979 and its 30th Mountain Brigade in 1980.[40] After Soviet advisors arrived in 1977, they inspired a number of adaptations and reorganisations.[41] In April 1982, the was moved from the capital. The division, which was commanded by Khalqi Major General Zia-Ud-Din, had its depleted combat resources spread out along the Kabul-Kandahar highway.[42] In 1984–1985, all infantry divisions were restructured to a common design. In 1985 Army units were relieved of security duties, making more available for combat operations.

During the 1980s Soviet–Afghan War, the Army fought against the mujahideen rebel groups. Deserters or defectors became a severe problem. The Afghan Army's casualties were as high as 50–60,000 soldiers and another 50,000 soldiers deserted the Army. The Afghan Army's defection rate was about 10,000 soldiers per year between 1980 and 1989; the average deserters left the Afghan Army after the first five months.[43]

Local militias were also important to the Najibullah regime's security efforts. From 1988 several new divisions were formed from former Regional Forces/militias' formations: the , , 80th, 93rd, 94th, 95th, and 96th, plus, possibly, a division in Lashkar Gah.[44]

As compensation for the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, the USSR agreed to deliver sophisticated weapons to the regime, among which were large quantities of Scud surface-to-surface missiles.[45] The first 500 were transferred during the early months of 1989, and soon proved to be a critical strategic asset. During the mujahideen attack against Jalalabad, between March and June 1989, three firing batteries manned by Afghan crews advised by Soviets fired approximately 438 missiles.[46] Soon Scuds were in use in all the heavily contested areas of Afghanistan. After January 1992, the Soviet advisors were withdrawn, reducing the Afghan Army's ability to use their ballistic missiles. On April 24, 1992, the mujahideen forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud captured the main Scud stockpile at Afshur. As the communist government collapsed, the few remaining Scuds and their TELs were divided among the rival factions fighting for power. However, the lack of trained personnel prevented a sustained use of such weapons, and, between April 1992 and 1996, only 44 Scuds were fired in Afghanistan.[46]

1992 and after

In spring 1992, the Afghan Army consisted of five corps – at Jalalabad, 2nd at Khandahar, at Gardez,[47] 4th Corps at Herat, and 6th Corps at Kunduz – as well as five smaller operations groups, including one at Charikar, which had been 5th Corps until it was reduced in status. 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Corps, and the operations groups at Sarobi and Khost, nearly completely disintegrated in 1992.[48] Formations in and around Kabul joined different mujahideen militias while forces in the north and west remained intact for a longer period. Forces in the north and west were taken over by three major commanders: Ismael Khan, Ahmed Shah Masoud, and Abdul Rashid Dostam.

On 18 April 1992, the PDPA garrison at Kunduz surrendered to local mujahideen commanders.[49] The base at Kunduz was handed over to the overall military leader of Ittehad in the area, Amir Chughay. Dostum and commanders loyal to him formed Junbesh I-Melli, the National Islamic Movement of Afghanistan.[50] It grouped the former regime's 18th, 20th, 53rd, 54th, and 80th Divisions, plus several brigades.[51] By mid-1994 there were two parallel 6th Corps operating in the north. Dostum's 6th Corps was based at Pul-i-Khumri and had three divisions. The Defence Ministry of the Kabul government's 6th Corps was based at Kunduz and also had three divisions, two sharing numbers with formations in Dostum's corps.[52] By 1995 Masoud controlled three corps commands: the Central Corps at Kabul, the best organised with a strength of 15–20,000, the 5th Corps at Herat covering the west, and the 6th Corps at Kunduz covering the northeast.[53]

This era was followed by the Taliban Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in 1996, which aimed to control the country by Islamic Sharia law. The Taliban's army and commanders placed emphasis on simplicity;[54] some were secretly trained by the Pakistan Inter-Services Intelligence and Pakistani Armed Forces around the Durand Line. After the removal of the Taliban government through the United States invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001, private armies loyal to warlords gained more and more influence. In mid-2001, Ali Ahmed Jalali wrote:[55]

The army (as a state institution, organized, armed, and commanded by the state) does not exist in Afghanistan today. Neither the Taliban-led "Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan" nor the "Islamic State of Afghanistan" headed by the ousted President Rabbani has the political legitimacy or administrative efficiency of a state. The militia formations they command are composed of odd assortments of armed groups with varying level of loyalties, political commitment, professional skills, and organizational integrity. Many of them feel free to switch sides, shift loyalties, and join or leave the group spontaneously. The country suffers from the absence of a top political layer capable of controlling individual and group violence. ... Although both sides identify their units with military formations of the old regime, there is hardly any organizational or professional continuity from the past. But these units really exist in name only ... [i]n fact only their military bases still exist, accommodating and supporting an assortment of militia groups.

Formations in existence by the end of 2002 included the 1st Army Corps (Nangarhar), 2nd Army Corps (Kandahar, dominated by Gul Agha Sherzai), 3rd Army Corps (Paktia, where the US allegedly attempted to impose Atiqullah Ludin as commander), 4th Army Corps (Herat, dominated by Ismail Khan), 6th Army Corps at Kunduz, 7th Army Corps (under Atta Muhammad Nur at Balkh[56]), 8th Army Corps (at Jowzjan, dominated by Dostum's National Islamic Movement of Afghanistan) and the Central Army Corps around Kabul.[57][58] In addition, there were divisions with strong links to the centre in Kabul. These included the 1st in Kabul, 27th in Qalat, 31st in Kabul, 34th in Bamiyan (4th Corps),[59] 36th in Logar, 41st in Ghor, 42nd in Wardak, 71st in Farah, and 100th in Laghman.[60]

The International Crisis Group wrote:[61]

New divisions and even army corps were created to recognise factional realities or undermine the power base of individual commanders, often without regard to the troop levels normally associated with such units. For example, the ministry in July 2002 recognised a 25th Division in Khost province, formed by the Karzai-appointed governor, Hakim Taniwal, to unseat a local warlord, Padshah Khan Zadran, who was then occupying the governor's residence. At its inception, however, the division had only 700 men – the size of a battalion.

Even by December 2004 Human Rights Watch was still saying in an open letter to Karzai that: "Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf, the head of the Ittihad-i Islami faction and the Daw'at-e Islami party [should be curbed]. Sayyaf has no government post but has used his power over the Supreme Court and other courts across the country to curtail the rights of journalists, civic society activists, and even political candidates. He also controls militias, including forces recognized as the 10th Division of the Afghan army, which intimidate and abuse Afghans even inside Kabul. We ask that you express public opposition to Sayyaf's activities, explicitly state your opposition to such misuse of unofficial authority, and move expeditiously to disarm and demobilize armed forces associated with Ittihad-i Islami and other unofficial forces."[62][63]

Afghan National Army

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: The latest information is from 2014. (November 2019) |

The Afghan National Army was founded with the issue of a decree by President Hamid Karzai on December 1, 2002.[64] Upon his election Karzai set a goal of an Army of at least 70,000 soldiers by 2009. However, the Afghan Defense Minister, Abdul Rahim Wardak, said that at least 200,000 active troops were needed.[65] The Afghan Ministry of Defence also loudly objected to the smaller, volunteer, nature of the new army, a change from the previous usage of conscripts.[66] The US also blocked the new government from using the army to pressure Pakistan.

The first new Afghan kandak (battalion) was trained by British Army personnel of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), becoming 1st Battalion, Afghan National Guard.[67] Yet while the British troops provided high quality training, they were few in number. After some consideration, it was decided that the United States might be able to provide the training. Thus follow-on kandaks were recruited and trained by 1st Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group.[68] 3rd SFG built the training facilities and ranges for early use, using a Soviet built facility on the eastern side of Kabul, near the then ISAF headquarters.

Recruiting and training commenced in May 2002, with a difficult but successful recruitment process of bringing hundreds of new recruits in from all parts of Afghanistan.[69][67] Training was initially done in Pashto and Dari (Persian dialect) and some Arabic due to the very diverse ethnicities. The original US target in April 2002 was that of 12,000 men trained by April 2003, but it was quickly realised that this was too ambitious, and the requirement reduced to only 9,000, to be ready by November 2003. The first female Afghan parachutist Khatol Mohammadzai, trained during the 1980s, became the first female general in the Afghan National Army in August 2002.[70] The National Military Academy of Afghanistan, a West Point analogue and part of the which is based in Qargha Garrison, was also established to produce officers. The curriculum of this academy is to complete a four year military and civil training in the aim of preparing the officer for the long-term. The NMAA taught four major foreign languages, vital to developing the relationship between the ANA and foreign armies.

US Army major objectives for ANA reconstruction in October 2002 were:[71]

- Ensure activation of Central Corps headquarters and its three Brigades by 1 October 2003

- Develop and begin implementation of Afghan MoD/General Staff reform plan

- Establish ANA institutional support systems including officer and NCO schools, ANA training and doctrine directorate, and garrison support elements

- Design and build OMC-A structure consisting of US/Coalition military, contractor, and Afghan civilian and military personnel capable of managing the ANA building program as it increases in scope and complexity

- Increase international and Afghan domestic support for and confidence in ANA through the maintenance of quality within the force and the conduct of effective information operations.

The first deployment outside Kabul was made by 3rd Kandak, ANA to Paktika Province, including Orgun, in January 2003.[72] By January 2003 just over 1,700 soldiers in five Kandaks (battalions) had completed the 10-week training course, and by mid-2003 a total of 4,000 troops had been trained. Approximately 1,000 ANA soldiers were deployed in the US-led Operation Warrior Sweep, marking the first major combat operation for Afghan troops. Initial recruiting problems lay in the lack of cooperation from regional warlords and inconsistent international support. The problem of desertion dogged the force in its early days: in the summer of 2003, the desertion rate was estimated to be 10% and in mid-March 2004, an estimate suggested that 3,000 soldiers had deserted. Some recruits were under 18 years of age and many could not read or write. Recruits who only spoke the Pashto language experienced difficulty because instruction was usually given through interpreters who spoke Dari.

The Afghan New Beginnings Programme (ANBP) was launched on 6 April 2003 and begin disarmament of former Army personnel in October 2003.[73] In March 2004, fighting between two local militias took place in the western Afghan city of Herat. It was reported that Mirwais Sadiq (son of warlord Ismail Khan) was assassinated in unclear circumstances. Thereafter a bigger conflict began that resulted in the death of up to 100 people. The battle was between troops of Ismail Khan and Abdul Zahir Nayebzada, a senior local military commander blamed for the death of Sadiq.[74] Nayebzada commanded the 17th Herat Division of the Afghan Militia Forces' 4th Corps. In response to the fighting, about 1,500 newly trained ANA soldiers were sent to Herat in order to bring the situation under control.

Beyond the fighting kandaks, establishment of regional structures began when four of the five planned corps commanders and some of their staff were appointed on 1 September 2004. The first regional command was established in Kandahar on September 19; the second at Gardez on September 22, with commands at Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat planned.[75] The Gardez command, also referred to in the AFPS story as the 203 Corps, was to have an initial force of 200 soldiers. Kandahar's command was the first activated, followed by Gardez and Mazar-e-Sharif. The Herat command was seemingly activated on 28 September. The next year, the ANA's numbers grew to around 20,000 soldiers, most of which were trained by forces of the United States. In the meantime, the United States Army Corps of Engineers had started building new military bases for the fast-growing ANA.

By March 2011, a National Military Command Center had been established in Kabul, which was being mentored by personnel from the Virginia Army National Guard.[76]

An increasing number of female soldiers also joined the ANA.

Troop numbers

Due to the strong Taliban insurgency and the many other problems that Afghanistan faced at the time, the ANA steadily expanded. By early 2013, reports stated that there were 200,000 ANA troops. However, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) said in January 2013:[77]

Determining ANSF strength is fraught with challenges. US and coalition forces rely on the Afghan forces to report their own personnel strength numbers. Moreover, the Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan (CSTC-A) noted that, in the case of the Afghan National Army, there is "no viable method of validating [their] personnel numbers." SIGAR will continue to follow this issue to determine whether US financial support to the ANSF is based on accurately reported personnel numbers.

| Number of soldiers on duty | Year(s) |

|---|---|

| 90,000 | 1978[78] |

| 100,000 | 1979[79] |

| 25 - 35,000 | 1980-1982[79][43][78] |

| 35 - 40,000 | 1983-1985[80][81][82] |

| 1,750 | 2003[83] |

| 13,000 | 2004[84] |

| 21,200 | 2005[85] |

| 26,900 | 2006[86] |

| 50,000 | 2007[87] |

| 80,000 | 2008 |

| 90,000 | 2009 |

| 134,000 | 2010[88] |

| 164,000 | 2011[89] |

| 200,000 | 2012[90] |

| 194,000 | 2014[91] |

ANA personnel were trained by the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) under the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan.

Costs and salaries

Under the US–Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement, the United States designated Afghanistan as a major non-NATO ally and agreed to fund the ANA until at least 2024. This included soldiers' salaries, providing training and weapons, and all other military costs.

Soldiers in the Army initially received $30 a month during training and $50 a month upon graduation, though the basic pay for trained soldiers later rose to $165. This starting salary increased to $230 a month in an area with moderate security issues and to $240 in those provinces where there was heavy fighting.[92] About 95% of the men and women who served in the military were paid by electronic funds transfer.[93] Special biometrics were used during the registration of each soldier.[94]

Ineffectiveness

The Afghan National Army (ANA) were plagued by significant issues of poor cohesion, illiteracy, corruption and abuse. A quarter of ANA troops were reported to have deserted in 2009 with many troops hiding in the heat of battle rather than engaging the enemy.[95][96] It was reported that approximately 90% of ANA troops were illiterate and there were widespread instances of corruption with the ANA manpower consisting a high percentage of ghost battalions.[97][98] Another significant problem for the ANA was a high level of drug abuse amongst its soldiers. The Special Investigator General for Afghan Reconstruction reported the number of ANA soldiers using drugs was "at least 50 percent" and may be as high as 75 percent of all Afghan soldiers, according to some reports.[99]

Theft and a lack of discipline plagued many elements of the ANA. US trainers reported missing vehicles, weapons and other military equipment, and outright theft of fuel provided by the US to the ANA.[100] Death threats had been leveled against some US officers who tried to stop Afghan soldiers from stealing. Some Afghan soldiers often found improvised explosive devices and snipped the command wires instead of marking them and waiting for US forces to come to detonate them. The practice allowed insurgents to return and reconnect them.[100] US trainers frequently had to remove the cell phones from Afghan soldiers hours before a mission for fear that the operation would be compromised by bragging, gossip and reciprocal warnings.[101]

ANA troops engaged in fragging by turning on their own troops and troops of ISAF.[102] Fragging had worsened enough to the point where two decrees were issued by the U.S Defense Department in the summer of 2012 stating that all American personnel serving in Afghanistan were told to carry a magazine with their weapon at all times, and that when a group of American troops were present and on duty with ANA forces, one American serviceman had to stand apart on guard with a loaded weapon ready.[103] In addition to fragging, a report by a US inspector general revealed 5,753 cases of "gross human rights abuses by Afghan forces", including "routine enslavement and rape of underage boys by Afghan commanders".[104] The ineffectiveness of the ANA became most apparent during the 2021 Taliban offensive; thousands of ANA troops surrendered to the Taliban en masse, with many cities falling to the Taliban unopposed.[105]

Conflicts

Since its inception in 1722, the Afghan National Army had engaged the following entities in various conflicts:

- Empires

- Ottoman Empire - 1722–1727

- Safavid Empire - 1722, 1729

- Maratha Empire - 1757, 1758, 1761

- Sikh Empire - 1813

- Qajar Empire - 1837–1838

- British Empire - 1839–1842, 1878–1880, 1919

- Superpower

- Soviet Union - 1925–1926

In addition to dealing with external threats, the Afghan National Army dealt with significant levels of internal threats, including multiple uprisings and civil wars:

Training and International Partnerships

Various International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and Operation Enduring Freedom - Afghanistan contributing countries had undertaken different responsibilities in the creation of the ANA. All these various efforts were managed on the Coalition side by Combined Security Transition Command - Afghanistan (CSTC-A), a three-star level multi-national command headquartered in downtown Kabul. On the ANA side, all training and education in the Army was managed and implemented by the (ANATC), a two-star command which reported directly to the Chief of the General Staff. All training centers and military schools were under ANATC HQ. The coalition forces were partnered with the ANA to mentor and support formal training through Task Force Phoenix. This program was formalized in April 2003, based near the Kabul Military Training Center.

During the ISAF era, advisers in the US ETTs (Embedded Training Teams) or NATO OMLTs (Operational Mentor and Liaison Team) acted as liaisons between the ANA and ISAF. The ETTs and OMLTs coordinated operational planning and ensured that ANA units received enabling support.[106] Individual basic training was conducted primarily by Afghan National Army instructors and staff at ANATC's Kabul Military Training Center, situated on the eastern edge of Kabul. The US Armed Forces assisted in basic and advanced training of enlisted recruits, and also ran the Drill Instructor School which ran basic training courses for training NCOs. Basic training had been expanded to include required literacy courses for illiterate recruits. A French Army advisory team oversaw the training of officers for staff and platoon or toli (company) command in a combined commissioning/infantry officer training unit called the Officer Training Brigade (OTB). OTB candidates in the platoon and toli command courses were usually former militia and mujaheddin leaders with various levels of military experience. The United Kingdom also conducted initial infantry officer training and commissioning at the Officer Candidate School (OCS). OCS candidates were young men with little or no military experience. The British Army also conducted initial and advanced Non-Commissioned Officer training as well in a separate NCO Training Brigade.

The Canadian Forces supervised the Combined Training Exercise portion of initial military training, where trainee soldiers, NCOs, and officers were brought together in field training exercises at the platoon, toli (company) and kandak (battalion) levels to certify them ready for field operations. In the Regional Corps, Coalition Embedded Training Teams continued to mentor the kandak's leadership, and advised them in the areas of intelligence, communications, fire support, logistics and infantry tactics.

Formal education and professional development was conducted at two main ANATC schools, both in Kabul. The National Military Academy of Afghanistan, located near the Kabul International Airport, was a four-year military university which produced degree second lieutenants in a variety of military professions. NMAA's first cadet class entered its second academic year in spring 2006. A contingent of US and Turkish instructors jointly mentored the NMAA faculty and staff. The Command and General Staff College, located in southern Kabul, prepared mid-level ANA officers to serve on brigade and corps staffs. France established the CGSC in early 2004, and a cadre of French Army instructors continued to oversee operations at the school.

Sizable numbers of Afghan National Army Officers were sent to be trained in India either at the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun, the National Defence Academy near Pune or the Officers Training Academy in Chennai. The Indian Military Academy which had been in existence since 1932, provided a 4-year degree to ANA army officers, while the National Defence Academy provided a 3-year degree after which officers underwent a 1-year specialization in their respective service colleges. The Officers Training Academy provided a 49-week course to Graduate officer candidates. In 2014 the number of Afghan officers in training in India was nearly 1100.[107]

According to statements made by Colonel Thomas McGrath in October 2007, the coalition supporting the build-up of the ANA has seen progress and is pleased with the Afghan performance in recent exercises. McGrath estimated that the ANA should be capable of carrying out independent brigade-size operations by the spring of 2008.[108] Despite high hopes for the ANA, four years after McGrath's estimated date for independent brigade-size operations, not a single one of the ANA's 180 kandaks could carry out independent operations, much less an entire brigade.[109] On July 30, 2013, US Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense Peter Lavoy told reporters in Washington D.C., according to Jane's Defence Weekly, that '... a residual [US] force would be needed to help the ANSF complete more mundane tasks such as logistics, ensuring soldiers get their paychecks, procuring food, awarding fuel contracts, and more.'[110][111] Lavoy noted that the Afghans were still developing those skills and it would be "well beyond the 2014 date" before they were expected to be capable.

Size

A table of the size of the Afghan army over time is listed below.[112]

| Head of state | Year | Total | Trained/regular |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dost Mohammad Khan | 1857 | 25,000 | 7,400 |

| Sher Ali Khan | 54,900 | ||

| Abdur Rahman Khan | 88,400 | 88,400 | |

| Habibullah Khan | 20,000 | 4,000 | |

| Amanullah Khan | 10,000 | 10,000 | |

| Habibullāh Kalakāni | 20,000 | 4,000 | |

| Mohammed Nadir Shah | 72,000 | 70,000 | |

| Mohammad Hashim Khan | 82–92,000 | 80–90,000 | |

| Mohammed Zahir Shah | 82,000 | 80,000 | |

| Mohammad Najibullah | 1988 | 160,000 | 101,500 |

| Burhanuddin Rabbani | 1995 | 70,000 | |

| Taliban period | 100,000 | ||

| Hamid Karzai | 2003 | 49,000 | 4,000 |

Officers

Despite its size, the ANA had close to 1,000 officers with the rank of general which is more than the number of generals in the United States army.[113] Corruption was deeply rooted within the officer cadres with many officers holding loyalties with particular political factions. The endemic corruption engaged by these officers eroded the morale of the ANA.[114]

Structure

A January 2011 NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan information paper described the ANA as being led by the Chief of General Staff, supervising the Vice Chief of the General Staff, the Vice Chief of the Armed Forces (an Air Force officer), the Director of the General Staff, himself supervising the General Staff itself, and seven major commands. The ANA Ground Force Command, under a lieutenant general, directed the five ground forces corps and the . The other six commands included the ANA Special Operations Command, Army Support Command, the ANA Recruiting Command (ANAREC), the HSSB, and the Detainee Guard Force.[115]

Amongst support facilities was the ,[116] a Central Ammunition Depot.

Kandak

The basic unit in the Afghan National Army was the kandak (battalion), consisting of 600 troops. Kandaks could be further broken down into four toli (company).[117] Although the vast majority of kandaks were infantry, at least one mechanized and one tank kandak had been formed. Every ANA Corps was assigned commando kandaks.

Seven Quick Reaction Forces (QRF) kandaks were created in 2012–13, one kandak for each of the ANA's corps and divisions. They were created by converting existing infantry kandaks into QRF kandaks at the NMAA Armour Branch School. The QRF kandaks were trained and fielded in 2012 and 2013. The QRF kandaks were the first major ANA users of armoured vehicles.[118]

Corps

At its largest the ANA reached the size of seven corps; each corps was responsible for an area of the country. Establishment of the corps started when four regional commands were established with some staff in September 2004. For a period the Afghan National Army Air Corps was also among the corps, before being split off as a separate air force. Each corps had three to four subordinate brigades, and each brigade had four infantry kandaks (battalions) as basic fighting units. Each infantry kandak was assigned a specific area for which it is responsible for; the kandak's mission was to secure its area from internal and external threats. Originally, the four outlying corps were assigned one or two brigades, with the majority of the manpower of the Army based in Kabul's 201st Corps. This was superseded by a buildup in which each corps added extra brigades. Originally, the 2008 Combined Security Transition Command – Afghanistan size target was for a total of 14 brigades: 13 infantry, one mechanized, and one commando.

In 2019-2021 the regionally focused corps were as follows:

- 201st Corps (Kabul) – 1st Brigade was based at the Presidential Palace. 3rd Brigade, at Pol-e-Chakri, was to be a mechanised formation including M-113s[119] and Soviet-built main battle tanks (T-62s).[120] Later information from LongWarJournal.org placed most of the 3rd Brigade at Jalalabad, Second Brigade at Pol-e-Charkhi, and only a single kandak of First Brigade at the Presidential Palace.[121] The corps operational areas included Eastern Afghanistan, including Kabul, Logar, Kapisa, Konar, and Laghman. This included the Afghan capital of Kabul as well as vital routes running north and south, and valleys leading from the Pakistani border into Afghanistan.

- 203rd Corps (Gardez) The original Gardez Regional Command was established on 23 September 2004.[122] As of 2009, First Brigade, Khost, Second Brigade, Forward Operating Base Rushmore, Sharana, Paktika Province, Third Brigade, Ghazni. On 19 Oct 2006, as part of Operation Mountain Fury, two ETTs (Embedded Training Teams) mentored and advised a D30 artillery section from Fourth Kandak, Second Brigade, 203rd Corps, to conduct the first artillery missions during combat operations with harassment and indirect fires.[123] Three days later, they successfully conducted counterfire (with assistance from a US Q-36 radar) that resulted in ten enemy casualties, the highest casualties inflicted from artillery fire in ANA history.[citation needed] The corps is supported by the Gardez Regional Support Squadron of the AAF, equipped with 8 helicopters: 4 transport to support the corps' commando kandak, two attack, and two medical transport.[124]

- 205th Corps (Kandahar) – oversaw the provinces of Kandahar, Zabul, and 4th Brigade Urozgan under Brigadier General Zafar Khan's control.[125] It consisted of four brigades, a commando kandak and three garrisons. The corps had integrated artillery and airlift capacity, supplied by a growing Kandahar Wing of the Afghan Air Force.[126]

- 207th Corps (Herat) – 1st Brigade at Herat, 2nd Brigade at Farah, and elements at Shindand (including commandos).[127] The corps was supported by the Herat Regional Support Squadron of the AAF, equipped with eight helicopters: four transport to support the corps' commando kandak, two attack, and two medical transport aircraft.[124]

- 209th Corps (Mazar-i-Sharif) – Worked closely with the German-led Regional Command North, and had 1st Brigade at Mazar-i-Sharif and, it appears, a Second Brigade forming at Kunduz. An Army Corps of Engineers solicitation for Kunduz headquarters facilities for the Second Brigade was issued in March 2008.[128] The corps was supported by the Mazar-i-Sharif Regional Support Squadron of the AAF, equipped with eight helicopters: four transport to support the Corps' commando kandak, two attack, and two medical transport helicopters.[124] In October 2015, as a response to the fall of Kunduz, reports came that a new division would be formed in the area.[129]

- 215th Corps (Lashkar Gah) – In 2010, the Afghan government approved a sixth corps of the Afghan National Army – Corps 215 Maiwand – to be based in the Helmand capital of Lashkar Gah. The 215th was developed specifically to partner with the Marine Expeditionary Brigade in Helmand.[130] On 28 January 2010, Xinhua reported that General Sayed Mallok would command the new corps.[131] The corps will cover all parts of Helmand, half of Farah and most parts of southwestern Nimroz province. The corps was formally established on 1 April 2010. 1st Bde, 215th Corps, is at Garmsir, partnered with a USMC Regimental Combat Team.[132] Elements of 2nd Brigade, 215th Corps, had been reported at Forward Operating Base Delaram, Farah Province. 3rd Bde, 215th Corps, partnered with the UK Task Force Helmand is at Camp Shorabak.[133]

- 217th Corps (Headquarters Kunduz) – The Afghan army established a new corps in 2019. The 20th Division, which was formerly part of the 209th Corps, became the 217th Corps. The corps was given responsibility for Kunduz Province, Takhar, Baghlan, and Badakhshan provinces.[134] In August 2021, the Taliban seized control of the corps headquarters and Kunduz as part of the 2021 Taliban offensive.[135]

In late 2008 it was announced that the 201st Corps' former area of responsibility would be divided, with a Capital Division being formed in Kabul and the corps concentrating its effort further forward along the border. The new division, designated the 111th Capital Division, became operational in April 2009.[136] It had a First Brigade and Second Brigade (both forming) as well as a Headquarters Special Security Brigade.

ANA Special Operations Command

This section needs to be updated. (July 2021) |

From mid-2011, the ANA began establishing an ANA Special Operations Command (ANASOC) to control the ANA Commando Brigade and the ANA Special Forces. It is headquartered at Camp Moorehead in Wardak Province, located six miles south of Kabul.[137][138] In 2011, ANASOC consisted of 7,809 commandos and 646 special forces personnel.[139]

In July 2012, the Special Operations Command was officially established as a division-sized special operations force formation, including a command and staff. The command, with the status of a division, now boasts between 10,000 and 11,000 special operations soldiers.[140][141] Previously this was organised as one brigade with 8 kandaks, all with a minimum of 6 companies. Due to the standard size of a brigade in the ANA, the ANASOC is likely to be split into 3 – 4 brigades, one of which will be a Special Forces Brigade.

ANASOC now has an attached Air Force Special Mission Wing which was inaugurated in July 2012.[142] With the December 2017 approval of the FY 2018 tashkil, ANASOC is authorized 16,040 personnel, organized into four Special Operations Brigades (SOB) and a National Mission Brigade (NMB).[139]

ANA Commando Corps

In July 2007 the ANA graduated its first commandos. The commandos underwent a grueling three-month course being trained by American Special Operations Forces. They were fully equipped with US equipment and had received specialized light infantry training with the capability to conduct raids, direct action, and reconnaissance in support of counterinsurgency operations; and they provided a strategic response capability for the Afghan government.[143][144] By the end of 2008, the six ANA commando battalions were stationed in the southern region of Afghanistan assisting the Canadian forces. As of 2017, the commando brigade grew into corps size with 21,000 commandos, with their number eventually reaching 30,000 commandos. ANA commando force comprised only seven percent of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces, however they engaged in 70 percent to 80 percent of the fighting during the War in Afghanistan.[145]

During the 2021 Taliban offensive, the ANA Commando Corps fought tenaciously and were seen as the Afghan military's best-trained and most highly motivated troops. The commandos were deployed on mass across a vast geographical area, however this isolated many units as they were abandoned by other ANA units and locals. In June 2021, 50 commandos managed to recapture Dawlat Abad from the Taliban, however after receiving no reinforcements, commandos were encircled and made a desperate last stand. Those that survived and were captured were executed by the Taliban.[146][147]

Special Security Forces

A special operations unit was first conceptualized in 2009 and established in 2010.[148] Currently, there were at least two special operations brigades (1st, 2nd) and a National Mission Brigade, which included the 6th Special Operations Kandak (SOK), Ktah Khas (KKA), and two Special Forces Kandaks.[139]

The first Special Forces team, whose soldiers were selected from the ANA Commandos (this practice was discontinued later to preserve commando capability), finished training in May 2010. The organization was based on the US Army Special Forces.[149][150] Initially all the Special Forces candidates were planned to come from the Commando Kandak (Commando Battalion), only requiring 10 weeks of training. However, after the initial period it was planned that Special Forces recruiting was to be conducted throughout the Army, and initial Special Forces training was to be 15 weeks. Commando graduates of the special forces course would retain their 'commando' tab and would also have a 'special forces' tab on top of the commando tab in addition to receiving a tan beret. These candidates were normally selected after serving four years as a Commando.[148]

In May 2010 the first class of the ANA Special Forces graduated from their 10-week qualification course and moved on to the operational portion of their training. In November 2010, the ANA Special Forces Class 1 received their tan berets in a ceremony at Camp Morehead, Kabul Province, after completing 26 weeks of on-the-job training partnered with US Special Forces. The initial selection involved taking the 145 commandos who volunteered, putting them through a one-week qualification process (similar to the one used in the United States), and finding, as in the US, that only about half (69) passed. These Special Forces operators formed the first four A-Teams (of 15 men each). Some of them who passed the 1st were being used to help US Special Operations Forces train the 2nd class of candidates.[151] Special Forces soldiers were trained to focus on interacting with the population through jirgas with village elders, but capable of unilateral operations.[152] A second ANA Special Forces class completed training in December 2010.[153]

The force numbered 646 Special Forces operators in December 2011.[139] This unit also had female Special Forces operators to interact with female civilians, such as searches, interviews or medical examinations. There were plans to create one Special Forces platoon of just female operators so they could interact with women and children.[148]

Afghan Border Force

The Afghan Border Force (ABF) was responsible for the security of Afghanistan's border area with neighboring countries extending up to 30 miles (48 km) into the interior.[154] In December 2017, most of the Afghan Border Police (ABP) personnel of the Afghan National Police were transferred to the Afghan National Army to form the ABF.[155] The Afghan National Police retained 4,000 ABP personnel for customs operations at border crossings and international airports.[156] The ABF consisted of seven brigades.[157]

Afghan National Civil Order Force

The Afghan National Civil Order Force (ANCOF) was responsible for civil order and counterinsurgency.[158] In March 2018, most of the Afghan National Civil Order Police (ANCOP) personnel of the Afghan National Police were transferred to the Afghan National Army to form the ANCOF with their role remaining the same.[159][157] The remaining 2,550 ANCOP personnel in the Afghan National Police formed the Public Security Police (PSP).[157] The ANCOF consisted of eight brigades.[160] In June 2020, the ANA began disbanding the ANCOF brigades with personnel to be integrated into ANA Corps.[158]

Combat support units

As the ANA grew, the focus changed to further developing the force so that it could become self-sustaining. The development of the ANA Combat Support Organizations, the Corps Logistics Kandaks, or Combat Logistics Battalions (CLK) and the Combat Support Kandaks, or Combat Support Battalions, (CSK) was vital to self-sustainability. Combat Support Kandaks (CSK) provided specialized services for infantry kandaks. While most ANA kandaks had a CSK, they were underdeveloped and did not fit the requirements of a growing army. The CSK role includes motor fleet maintenance, specialized communications, scouting, engineering, and long range artillery units. Eventually one fully developed CSK was to be assigned to each of the 24 ANA combat brigades.[118] Each CSK included an Intelligence toli (company) called a Cashf Tolai. Each company was responsible for collecting information about the surrounding area and Taliban activities.[161] The members of the unit interacted closely with the local residents in an effort to deny the enemy control over the surrounding area.[162]

In order to enable the ANA to be self-sufficient, brigades were to form a Corps Logistics Kandaks (CLK) which was responsible for providing equipment to the 90 infantry kandaks. The CSK was responsible for the maintenance of the new heavier equipment including APCs.[118] In the 215th Corps area, the US Marine Combat Logistics Battalion 1 announced in January 2010 that the training of the ANA 5th Kandak, 1st Brigade, 215th ANA Corps Logistics Kandak has gone very well and that the unit was capable of undertaking the majority of day-to-day activities on their own.[163] The ANA never achieved self-sufficiency and after losing logistical and air support from the U.S, the ANA fell apart during the 2021 Taliban offensive, making a series of negotiated surrenders.[13]

Ranks

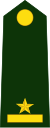

- Commissioned officer ranks

The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General/flag officers | Field/senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| مارشال Marshal |

ستر جنرال Setar jenral |

ډگرجنرال Dagar jenral |

تورن جنرال Turan jenral |

برید جنرال Brid jenral |

ډگروال Dagarwal |

ډگرمن Dagarman |

جگرن Jagran |

جگتورن Jag turan |

تورن Turan |

لمړی بريدمن Lomri baridman |

دوهم بریدمن Dvahomi baridman |

دریم بریدمن Dreyom baridman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Other ranks

The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سرپرگمشر قدمدار Serebergemser qadamdar |

معاون سرپرگمشر قدمدار Maawan serebergemser qadamdar |

سرپرگمشر Serebergemser |

معاون سرپرگمشر Maawan sarpargamshar |

پرگمشر Pregmesher |

جندي Jondi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnic composition

In 2003, the United States issued special guidelines to ensure ethnic balance in the ANA.[164] By late 2012, the ANA was composed of 43% Pashtuns, 32% Tajiks, 12% Hazaras, 8% Uzbeks, and the rest were smaller ethnic groups of Afghanistan.[165] However, the army dis not track the actual ethnic composition of the officer corps, so it's difficult to know if the quotas were really fulfilled. There were no quotas for the enlisted soldiers.[166]

Equipment

Since the early 1970s, the Afghan Army had been equipped with the Soviet AK-47 as its main service rifle. As a major non-NATO ally of the United States, Afghanistan continued to receive billions of dollars in military assistance and the American M16 rifle served alongside the AK-47 as a main service rifle. Additional U.S made military hardware that formed part of the Afghan National Army arsenal included various rifles, bulletproof vests, night vision goggles, trucks and MRAPs. The ANA previously had a contract with International Trucks that would provide a fleet of 2,781 trucks which could be used for transporting personnel, water, petroleum and as a recovery vehicle.

Besides NATO, Afghanistan had increasingly turned to its regional allies, India and Russia for military aid and supplies. Both countries supported the Northern Alliance, with funding, training, supplies and medical treatment of wounded fighters, against the Taliban for years prior to the US-led intervention in 2001.

After the removal of the Taliban government in late 2001, India has been helping with several billion dollars invested in infrastructure development projects in Afghanistan besides the training of Afghan officers in India. But India has been unwilling to provide military aid unless under an UN-authorised peacekeeping mission. In 2014, India signed a deal with Russia and Afghanistan where it would pay Russia for all the heavy equipment requested by Afghanistan instead of directly supplying them. The deal also includes the refurbishment of heavy weapons left behind since the Soviet war.[107][167] Following the end of the 2021 Taliban offensive, much of the Afghan National Armies arsenal including much of its U.S military hardware ended up in the hands of the Taliban.[168]

Quick Reaction Force vehicles

The Quick Reaction Force (QRF) kandaks were being organized as motorized infantry equipped with 352 Mobile Strike Force Vehicles (MSFV). Shipments of the vehicles began in November 2011,[169] and the ANA took possession of the first 58 in March 2012.[170]

There was some confusion over the exact amount and type of vehicles in the QRF with various sources giving different figures. While some sources reporting on the formation of the QRF state that 440–490 M1117s had been ordered, it is unclear whether all of these were assigned to the QRF.[171][172] The first 18 M1117s were sent to Afghanistan in November 2011.[169] In March 2012 the ANA took delivery of the first 58 of 352 MSFVs which included some or all of the M1117s.[170] Other sources reported that 352 MSFV (which include M1117s) would be supplied to the ANA.[170][173]

It is likely that 281 of the 352 MSFV would be M1117 Armored Security Vehicle while the other 71 would be other vehicle types including the Navistar 7000 series Medium Tactical Vehicles (MTV), the 4x4 chassis of which is used for the MRAP. The US had ordered 9900 of the International MaxxPro MRAP configuration alone for the Afghan National Army and the Iraqi Army.[174] Additional support vehicles will also be required to maintain a force such as this in the field.

In order to use the MSFV, the members of the quick reaction forces had to be trained in their upkeep and maintenance. This began by training Afghan instructors who helped to pass on the knowledge to the Quick Reaction Forces members with increasing levels of responsibility. Most of the training was being undertaken by American and French instructors.[170]

The United States Army reported that the Quick Reaction Forces would be equipped with 352 Mobile Strike Force Vehicles or MSFVs. The MSFV is an updated version of a vehicle supplied by Textron Marine & Land Systems who also produce the M1117. The MSFV utilizes off the shelf parts where possible, significantly reducing costs. The standard MSFV APC can be supplied in three options: Gunner Protection Kit, with turret and as an armored ambulance. By November 14, 2011, 18 had been delivered.[175] It is currently not clear whether the 281 MSFVs are in addition to the 490 M117s or part of the order.

In March 2012 Textron Marine & Land Systems who have produced all of the existing MSFVs were awarded a contract for an additional 64 MSFV to be sent to Afghanistan. These will again be based on the M117. Three variants of MSFV are with Turret, MSFV with Objective Gunner Protection Kit; and MSFV Ambulance.[176][177] In April 2012 it was announced that a second option to supply a further 65 MSFV in all three variants has been awarded to Textron Marine & Land Systems. This brings the total number of MSFVs to 369.[178] By 7 March 2013 the Textron had received orders for 634 MSFVs. They report that 300 of these have already been fielded.[179]

References

Citations

- ^ "ANA Recruits Commit Loyalty to God, Country and Duty". DVIDS.

- ^ "A Tale of Two Afghan Armies | Small Wars Journal". smallwarsjournal.com.

- ^ "Allah Duty Homeland", Afghanistan Ministry of Defence

- ^ "How the Afghan Army Collapsed Under the Taliban's Pressure". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Library of Congress Country Study Afghanistan, 1986, 290–291.

- ^ Giustozzi 2016.

- ^ "Bomb blast hits Afghanistan on security handover day". Deutsche Welle. Deutsche Welle. 19 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013. and "Karzai announces Afghan security handover". Agence France-Presse. Global Post. 18 June 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Operation Freedom's Sentinel: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, April 1, 2019 – June 30, 2019" (PDF). Department of Defense Office of the Inspector General. 20 August 2019. p. 26. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Engel Rasmussen, Sune. "Afghanistan's 'ghost soldiers': thousands enlisted to fight Taliban don't exist". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Sriram, Akash. "Ghost soldiers emblematic of a problem that has plagued Afghanistan's security for decades — corruption". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Editor, Analysis by Nic Robertson, International Diplomatic. "Afghanistan is disintegrating fast as Biden's troop withdrawal continues". CNN. Retrieved 2021-08-15.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Natasha Turak, Amanda Macias, and Emma Graham (August 18, 2021). "Ousted Afghan President Ashraf Ghani resurfaces in UAE after fleeing Kabul, Emirati government says". cnbc.com. Retrieved August 18, 2021.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Opinion | Why Afghan Forces So Quickly Laid Down Their Arms". 16 August 2021.

- ^ Chaturvedi, Amit. "Choppers, rifles, humvees: What Taliban captured during Afghanistan blitzkrieg". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Cooper, Helene (2021-08-14). "Taliban Sweep in Afghanistan Follows Years of U.S. Miscalculations". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ "'Northern Alliance' flag hoisted in Panjshir in first resistance against Taliban". Hindustan Times. 2021-08-17. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ Regencia, Tamila Varshalomidze,Usaid Siddiqui,Ted. "Biden keeps to August 31 deadline for Kabul airlift". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th. (1993). E.J. Brill's first encyclopedia of Islam 1913–1936. BRILL. pp. 150–51. ISBN 978-90-04-09796-4. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. pp. 29–31. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree; et al. "Last Afghan empire". The Online Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Yapp, M.E. Journal Article The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 338.

- ^ Ali Ahmad Jalali, Parameters, 2002.

- ^ Mark Sedra, Security Sector Reform in Afghanistan: An Instrument of the State-Building Project, in Andersen, Moller, and Stepputat, 'Fragile States and Insecure People: Violence, Security, and Statehood in the Twenty-first Century,' Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, 153, citing Jalali, Parameters, 2002, 76.

- ^ Frank Clements, Conflict in Afghanistan: A Historical Encyclopedia, 2–3.

- ^ Peter Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan, Public Affairs, 2011, 90.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2013-08-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Angelo Rasanayagam, Afghanistan: A Modern History, 2005, 36.

- ^ "АФГАНИСТАН. 1919-1978 гг. / Секретные войны Советского Союза". www.xliby.ru.

- ^ Azimi 2019.

- ^ Брудерер Г. Афганская война. Frankfurt am Main. 1995. С. 43.

- ^ Library of Congress Country Studies, Afghanistan: A Country Study, American University, 1986, Chapter 5: National Security, p.288-289.

- ^ Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and Confrontation. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1994. p. 986.

- ^ Isby 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Isby 1986, p. 19.

- ^ Urban, Mark (1988). War in Afghanistan. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0-333-43263-1.

- ^ Reported as part of 2nd Corps 1985. Central Intelligence Agency, "The Afghan Army: The Soviet Military's Poor Student," NESA, January 1985 (CIA FOIA).

- ^ Independent from any corps in 1985. Central Intelligence Agency, "The Afghan Army: The Soviet Military's Poor Student," NESA, January 1985 (CIA FOIA).

- ^ Urban, Mark (1988). War in Afghanistan. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-333-43263-1.

- ^ Jane's Military Review 1982–1983, David C. Isby, Ten Million Bayonets, Orion Publishing Group Ltd, 1988, Christopher F. Foss, Jane's Main Battle Tanks 1986–1987, Jane's Publishing Company Ltd, 1986: 'The order of battle of the.. army includes 11 infantry divs and 3 armoured divs, which like the rest of the army are under strength due to the internal problems within the country' (p.158)

- ^ Urban 1988, p.55, citing Asia Week, 30 May 1980.

- ^ Olga Oliker, 'Building Afghanistan's Security Forces in Wartime: The Soviet Experience,' RAND monograph MG1078A, 2011, p.38-39

- ^ Jane's Defence Weekly, Vol. 4, 1985, p.1148.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amtstutz 1986, p. 180.

- ^ Antonio Giustozzi (2000). War, Politics, and Society in Afghanistan. Hurst. p. 220. ISBN 9781850653967. See also Davis 1993 and Davis 1994.

- ^ "SS-1 'Scud' (R-11/8K11, R-11FM (SS-N-1B) and R-17/8K14)". Jane's Information Group. 26 April 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zaloga, p. 39

- ^ 3rd Corps, by the AMF period, 'theoretically incorporated 14th Division, 30th Division, 822nd Brigade, Border Brigades, and approximately 800.. in the Governor's Force in Paktya, Ghazni, Paktika, and Khost Provinces. Bhatia and Sedra 2008, 209.

- ^ See Anthony Davis, 'The Afghan Army,' Jane's Intelligence Review, March 1993, and also, later, Anthony Davis, 'The Battlegrounds of Northern Afghanistan,' Jane's Intelligence Review, July 1994, p.323 onwards

- ^ Nils Wormer, 'The Networks of Kunduz: A History of Conflict and their actors from 1992 to 2001,' Afghan Analysts Network, August 2012, 10.

- ^ Giustozzi 2004.

- ^ Giustozzi 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Anthony Davies, Jane's Intelligence Review, July 1994.

- ^ Davies, 1995, p.317, cited in Fontini Christia, 'Alliance Formation in Civil Wars,' Cambridge University Press, 2012, p.68. See also p.257 and citation of Anthony Davis (March 1993). "The Afghan Army". Jane's Intelligence Review: 134–139.

- ^ Giustozzi 2016, p. 121.

- ^ Ali A. Jalali, Afghanistan: The Anatomy of an Ongoing Conflict Archived 2016-12-10 at the Wayback Machine, Parameters, Spring 2001, pp. 85–98.

- ^ ReliefWeb ť Document ť Army develops despite militia disarmament issues Archived February 11, 2011, at archive.today and Mukhopadhyay, Dipali. "Disguised warlordism and combatanthood in Balkh: the persistence of informal power in the formal Afghan state." Conflict, Security & Development 9, no. 4 (2009): 535–564.

- ^ Antonio Giustozzi, 'Military Reform in Afghanistan,' in Confronting Afghanistan's Security Dilemmas, Bonn International Centre for Conversion, Brief 28, September 2003, pp. 23–31, see also Ali A. Jalali, 'Rebuilding Afghanistan's National Army', Parameters, November 2002, notes 20–25

- ^ "Afghanistan - Militia Facilities". www.globalsecurity.org.

- ^ Bhatia & Sedra 2008, p. 283.

- ^ Globalsecurity.org, Afghan Military Forces, accessed August 2013.

- ^ ICG, "Disarmament and Reintegration in Afghanistan," Asia Report N°65, 30 September 2003, p.3, citing Antonio Giustozzi, "Re-building the Afghan Army", paper presented during a joint seminar on "State Reconstruction and International Engagement in Afghanistan" of the Centre for Development Research, University of Bonn, and the Crisis States Program, Development Research Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science, 30 May-1 June 2003, Bonn.

- ^ "Afghanistan: An open letter to president Hamid Karzai - Afghanistan". ReliefWeb.

- ^ https://jfcbs.nato.int/rsm/newsroom/2019/national-military-academy-of-afghanistan-graduates-513-cadets

- ^ Retrieved August 2009. Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CBCNews: "Defence minister says Afghan Army must be 5 times larger" Archived 2008-01-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Giustozzi 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Giustozzi 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Terrence K. Kelly, Nora Bensahel, Olga Oliker, Security Force Assistance in Afghanistan: Identifying Lessons for Future Efforts, RAND Corporation, 2011, 22.

- ^ Kelly et al. 2011

- ^ Haseena Sullaiman (2 March 2005). "Woman Skydiver Leaps Ahead". Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

- ^ Jason Howk, Security Sector Reform/Building in Afghanistan, Strategic Studies Institute, 16.

- ^ Carlotta Gall (January 25, 2003). "An Afghan Army Evolves From Fantasy to Slightly Ragged Reality". The New York Times.

- ^ Bhatia & Sedra 2008, p. 122-127.

- ^ "Afghan aviation minister assassinated Slaying sparks factional fighting in western city". The Boston Globe. March 22, 2004. Retrieved 2013-06-29. and "Afghan minister killed in Herat". BBC News. 21 March 2004. Retrieved 2013-06-29. and "Afghan Aviation Minister Shot Dead". FOX News. Associated Press. March 21, 2004. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ "Defense.gov News Article: Afghan National Army Activates Second Regional Command". web.archive.org. August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Virginia National Guard's 29th Infantry Division mentors making a diff". National Guard.

- ^ SIGAR Report to Congress, January 30, 2013, pp. 73–74, cited in Cordesman, THE Afghan WAR IN 2013: MEETING THE CHALLENGES OF TRANSITION – VOLUME III SECURITY AND THE ANSF, working draft, March 28, 2013, 58.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Far East and Australasia 2003. Routledge. 2002. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arnold, Anthony (1983). Afghanistan's Two-party Communism: Parcham and Khalq. Hoover Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8179-7792-4.

- ^ Amtstutz 1986, p. 181.

- ^ Bonosky, Phillip (2001). Afghanistan–Washington's secret war. International Publishers. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-7178-0732-1.

- ^ Levite, Ariel; Jenteleson, Bruce; Berman, Larry (1992). Foreign Military Intervention: The Dynamics of Protracted Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-231-07295-3.

- ^ SoldiersMagazine.com:"Soldiers – the Official U.S. Army Magazine – March 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-18. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ^ Rumsfeld, Donald (August 6, 2004). "Rumsfeld: Cost of Freedom for Iraq Similar to Bringing Democracy to Others". Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ^ US DoD: Afghan Army Has Made Great Progress, Says U.S. Officer. Washington. January 10, 2005 Archived December 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ US Dept. of State: Afghanistan National Security Forces. 31 January 2006. Archived February 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Over 153,000 troops fighting 20,000 combatants: NATO". Pajhwok Afghan News. June 6, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- ^ Khwaja Basir Ahmad (July 5, 2010). "ANA strength reaches 134,000". Pajhwok Afghan News. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- ^ Pellerindate, Cheryl (May 23, 2011). "Afghan Security Forces Grow in Numbers, Quality". American Forces Press Service. United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ^ Blenkin, Max (June 28, 2012). "Afghan National Army a work in progress". The Australian. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Karzais On The Run". StrategyPage. October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE BLOGGERS ROUNDTABLE WITH MAJOR GENERAL DAVID HOGG, DEPUTY COMMANDER-ARMY, NATO TRAINING MISSION-AFGHANISTAN. U.S. NAVY, OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS, FEBRUARY 18, 2010. (PDF). Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE BLOGGERS ROUNDTABLE WITH ARMY COLONEL Colonel Thomas Umberg. MAY 17, 2010. (PDF). Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ 111128-F-HS721-086 | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Flickr. Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ "US trainers bemoan Afghan corruption". UPI.com. 9 December 2009. Archived from the original on 20 December 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ "POLITICS: Afghan Army Turnover Rate Threatens US War Plans". 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ "US surge is big, Afghan army is crucial". MSNBC. Associated Press. 5 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ "Illiteracy undermines Afghan army". Air Force Times. 14 September 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ "Drug problem adding to challenge in Afghanistan," Chicago Tribune, January 31, 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dianna Cahn Troops fear corruption outweighs progress of Afghan forces. Stars and Stripes. December 9, 2009. Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ James Gordon Meek, Training Afghanistan troops gets tough for U.S. troops as trust issues worsen, New York Daily News, December 13, 2009

- ^ Sara, Sally (8 November 2011). "Afghan soldier shoots 3 diggers". ABC News.

- ^ "MSN News". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Annie Jacobsen, "Surprise, Kill, Vanish: The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins," (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2019), p. 411

- ^ WILKINSON, TRACY; BULOS, NABIH (13 August 2021). "U.S. troops' return to Afghanistan has ominous parallel to recent history in Iraq". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

Government soldiers have surrendered en masse, bequeathing the militants thousands of trucks, dozens of armored vehicles, antiaircraft guns, artillery and mortars, seven helicopters (seven others were destroyed) and a number of ScanEagle drones.

- ^ "Operational Mentor and Liaison Team (OMLT) Programme". Archived from the original on 2009-04-04. Retrieved 2007-12-09.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Nato.int. September 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b "India turns to Russia to help supply arms to Afghan forces". Reuters. 2014-04-30. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Jim Garamone and David Mays, American Forces Press Service Afghan, Coalition Forces Battle Taliban, Narcotics, Emphasize Training. Army.mil. October 19, 2007

- ^ Spencer Ackerman, "Not A Single Afghan Battalion Fights Without U.S. Help," Wired, September 26, 2011.

- ^ Daniel Wasserbly, 'Pentagon: ANSF would still require 'substantial' help after 2014,' Jane's Defence Weekly

- ^ "Transcript". www.defense.gov.

- ^ Giustozzi, Antonio (2008). "AFGHANISTAN: TRANSITION WITHOUT END". S2CID 54592886. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Being an Afghan General Is Nice Work if You Can Get It. And Many Do". The New York Times. 19 December 2016. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019.

- ^ Tollast, Robert. "How Afghanistan's Army was pulled apart by corruption and backroom deals". The National News. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan, 'Information Paper: Ministry of Defense: A Year in Review,' 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Afghan National Army takes over operations at Chimtallah National Ammunition Depot". DVIDS.

- ^ Tim Mahon. Basic steps: Afghan Army and police trainers and trainees see progress Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Training and Simulation Journal. February 01, 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Afghan National Army update: July 2011 – Threat Matrix. Longwarjournal.org (2011-07-21). Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ DefendAmerica.mil, Afghan Army gets armored personnel carriers Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, April 25, 2005

- ^ "Bagram-Kabul-Bagram". Archived from the original on 2006-10-19. Retrieved 2008-03-24.. Austin Bay Blog. 21 June 2005

- ^ CJ Radin, Long War Journal, 2007-8

- ^ Afghan National Army activates second regional command Archived 2010-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, September 23, 2004, AFPS

- ^ (First to Fire, "FA Journal", Jan/Feb 2007)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Afghan National Army Air Corps: February 2009 Update – FDD's Long War Journal". www.longwarjournal.org. February 20, 2009. Archived from the original on September 12, 2010.

- ^ Northshorejournal.org, Status Report from the Afghan South Archived 2009-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, December 2008

- ^ Phoenix Legacy Vol 1 Issue 2, Task Force Phoenix, January 31, 2009

- ^ Anthony Cordesman, 'Winning in Afghanistan: Afghan Force Development,' Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 14, 2006

- ^ FedBizOpps.gov, 38—Y—Construction Services for the Second Battalion, 209th headqauters facilities, ANA Kunduz Installation Phase II, Kunduz, Afghanistan. Retrieved August 2009.

- ^ Marty, Franz J. (10 February 2016). "Isolated Outposts: Badakhshan sitrep". Jane's Defence Weekly. 53 (6). ISSN 0265-3818.

- ^ Amazingly capable « Your experience may vary, 30 January 2010

- ^ "Military Corps formed to strengthen security in Taliban hotbed".

- ^ DVIDS – News – Afghan leaders recognize military progress in Helmand. Dvidshub.net (2011-04-17). Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ Danish chief visits UK advisors in Helmand – British Army Website. Army.mod.uk (2010-10-07). Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ "Operation Freedom's Sentinel: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, April 1, 2019 – June 30, 2019" (PDF). Department of Defense Office of the Inspector General. 20 August 2019. p. 27. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "Taliban seizes Afghan Army corps headquarters, 2 northern airports | FDD's Long War Journal". www.longwarjournal.org. August 12, 2021.

- ^ James Sims Change of Command at Camp Phoenix. Dvidshub.net. May 31, 2009. Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ Afghan National Army update, May 2011. The Long War Journal (2011-05-09). Retrieved on 2011-12-27.

- ^ US Department of Defense. "Gates Visits New Afghan Commando Training Site".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "ANA Special Operations Command (ANASOC)". www.globalsecurity.org.

- ^ Rose, Cory. "ANA Special Operations Command stands up first division in Afghan history". NATO Training Mission – Afghanistan Public Affairs. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "NATO Secretary General Witnesses Afghan Army Strength". eNews Park Forest. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "ANA Commissions Special Mission Wing". Us Department of Defense. Retrieved 14 December 2012.