Aghasi Khanjian

Aghasi Khanjyan | |

|---|---|

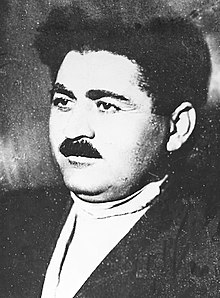

Khanjyan in 1934 | |

| First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia | |

| In office May 1930 – July 9, 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Haykaz Kostanyan |

| Succeeded by | Amatuni Vartapetyan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 30, 1901 Van, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | July 9, 1936 (aged 35) Tiflis, Georgian SSR, Transcaucasian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1919–1936) |

Aghasi Ghevondi Khanjian (Armenian: Աղասի Ղևոնդի Խանջյան; Russian: Агаси Гевондович Ханджян, Agasi Gevondovich Khandzhyan) (January 30, 1901 – July 9, 1936) was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia from May 1930 to July 1936.[1]

Biography[]

Khanjian was born in the city of Van, Ottoman Empire (today eastern Turkey).[2] With the onslaught of the Armenian genocide, his family emigrated from the city in 1915 and settled in Russian Armenia.[1][3] In 1917–19, he was one of the organizers of Spartak, the Marxist students' union of Armenia. He later served as the secretary of the Armenian Bolshevik underground committee.[3]

In September 1919, Khanjian was elected to the Transcaucasian regional committee of Komsomol. He enrolled in Sverdlov University in 1921. After graduating, he worked as a party official in Leningrad, where he supported Joseph Stalin against the city’s party boss, Grigory Zinoviev. He returned to Armenia in April 1928 and served as a secretary of the Armenian Communist Party in 1928–29, first secretary of the Yerevan City Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia, (March 1929–May 1930); and in May 1930, First Secretary of the Armenian Communist Party.[3]

Khanjian took over the leadership of the Armenian party at a time when the peasants were being forced to give up their land and were being driven onto collective farms, on instructions in Moscow. This provoked widespread resistance. The Soviet press revealed at the time that the communists lost control of parts of Armenia, which were in rebel hands for several weeks in March and April 1920.[4] Under Khanjian, the process was completed without any reports of armed clashes between rebels and the security services. He proved to be a charismatic Soviet politician and was very popular among the Armenian populace.[1] He was a friend and supporter of many Armenian intellectuals, including Yeghishe Charents (who dedicated a poem to him), Axel Bakunts and Gurgen Mahari (all three were subjected to political repressions after Khanjian's death).[3] Khanjian also tried unsuccessfully to have Moscow annex Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.[5] In a 1935 letter addressed to Stalin criticizing Khanjian, Armenian Bolshevik Aramayis Yerznkyan cited Khanjian's support for the unification of Kars, Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhijevan with Armenia as evidence of the latter's "nationalism".[6]

Death[]

Khanjian died under unclear circumstances in Tiflis (Tbilisi) on July 9, 1936. His death was officially declared a suicide, but according to many accounts, he was killed as a result of a political struggle with Lavrenti Beria.[7] Khanjian had openly opposed Stalin's decision to promote Beria to the leadership of the Transcaucasian SFSR in 1931, and Beria had been replacing many of Khanjian's allies in Armenia with his own in the lead up to Khanjian's death.[6] Ronald Grigor Suny describes the circumstances of his death as follows:

But by the mid-1930s Khanjian had come into conflict with the most powerful party leader in Transcaucasia, Lavrenti Beria, a Georgian close to Stalin.

Early in July 1936 Khanjian was called to Tiflis. Suddenly and unexpectedly it was announced that the Armenian party chief had committed suicide.[2] Though the circumstances of his death are murky, it is believed that Beria had ordered Khanjian's death to remove a threat to his own monopoly of power.[8]

Political condemnations of Khanjian came soon after his death. On July 20, 1936, Beria published an article in the newspaper Zarya Vostoka where he accused Khanjian of patronizing "rabid nationalist elements among the Armenian intelligentsia" and "abetting the terrorist group of [Armenian communist Nerses] Stepanyan".[7] In December 1936, the USSR's most prominent Armenian politician, Anastas Mikoyan, told the Central Committee that Khanjian had killed himself because "he didn't want to be a witness to his own universal shame". Stalin backed him up,[9] but a "much more plausible story", according to the Russian historian Roy Medvedev, is the one that Alexander Shelepin, Chairman of the KGB, told the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party in 1961: that Beria shot Khanjian dead, and put two forged suicide notes in his pocket.[10] Historian Boris V. Sokolov argues that it is likely that Khanjian committed suicide out of desperation, seeing his own arrest and death as imminent due to his former association with the disgraced and soon-to-be executed Grigory Zinoviev.[11]

Soon after Khanjian's death, his personal friend Yeghishe Charents wrote a series of seven sonnets dedicated to him titled "The Dauphin of Nairi: Seven Sonnets to Aghasi Khanjian".[6] Charents was arrested and died in prison in November 1937. According to Khanjian's successor Amatuni Vartapetyan, in the ten months after the former's death 1,365 people were arrested, among them 900 "Dashnak-Trotskyists" (Amatuni himself was arrested and shot in 1938).[7] Along with an entire generation of intellectual Armenian communist leaders (such as Vagarshak Ter-Vaganyan), Khanjian was denounced as an enemy of the people during the Great Purge.[1]

Khanjian was officially rehabilitated in 1956, three years after the death of Joseph Stalin and the arrest and execution of Lavrenti Beria.[11] In the proposal for the rehabilitation, Prosecutor General of the USSR Roman Rudenko attributed Khanjian's murder to Beria and his henchmen.[11]

See also[]

- Armenian SSR

- Vagarshak Arutyunovich Ter-Vaganyan

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Zev Katz, Rosemarie Rogers, Frederic Harned. Handbook of Major Soviet Nationalities. New York: Free Press, 1975, pp. 146-47.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Suny 1993, p. 156.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ханджян Агаси Гевондович in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1969–1978 (in Russian)

- ^ Conquest, Robert (1988). The Harvest of Sorrow, Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine. London: Arrow. p. 156. ISBN 0-09-956960-4.

- ^ Armenian History: History of Artsakh, Part 2[permanent dead link], Yuri Babayan

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gyulmisaryan, Ruben (July 9, 2021). "Մի սպանության պատմություն. Աղասի Խանջյան, 9 հուլիսի, 1936թ, Թիֆլիս" [History of a murder: Aghasi Khanjian, 9 July, 1936, Tiflis]. www.aniarc.am (in Armenian). Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Barseghyan, Artak R. (July 9, 2021). "Кто убил Агаси Ханджяна?" [Who killed Aghasi Khanjian?]. armradio.am (in Russian). Public Radio of Armenia. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny, "Soviet Armenia", The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St Martin's Press, 1997, p. 362.

- ^ J.Arch Getty, and Oleg V.Naumov (1999). Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939. New Haven: Yale U.P. p. 322. ISBN 0-300-07772-6.

- ^ Medvedev, Roy (1976). Let History Judge, The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. Nottingham: Spokesman. pp. 367–68.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sokolov, Boris (July 9, 2015). "Убивал ли Берия? Дело Ханджяна" [Did Beria Kill? The Khanjian Case]. www.aniarc.am (in Russian). ANI Armenian Research Center. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

Sources[]

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253207739.

Aghasi Khanjyan born in van.

- 1901 births

- 1936 deaths

- Party leaders of the Soviet Union

- Great Purge victims from Armenia

- People from Van, Turkey

- Armenian genocide survivors

- Communist Party of Armenia (Soviet Union) politicians

- Armenians of the Ottoman Empire

- Armenian atheists

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin