Aging-associated diseases

An aging-associated disease (commonly termed age-related disease, ARD) is a disease that is most often seen with increasing frequency with increasing senescence. Essentially, aging-associated diseases are complications arising from senescence. Age-associated diseases are to be distinguished from the aging process itself because all adult animals age, save for a few rare exceptions, but not all adult animals experience all age-associated diseases. Aging-associated diseases do not refer to age-specific diseases, such as the childhood diseases chicken pox and measles. "Aging-associated disease" is used here to mean "diseases of the elderly". Nor should aging-associated diseases be confused with accelerated aging diseases, all of which are genetic disorders.

Examples of aging-associated diseases are atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, cancer, arthritis, cataracts, osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and Alzheimer's disease. The incidence of all of these diseases increases exponentially with age.[1]

Of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds—100,000 per day—die of age-related causes.[2] In industrialized nations, the proportion is higher, reaching 90%.[2]

Patterns of differences[]

By age 3 about 30% of rats have had cancer, whereas by age 85 about 30% of humans have had cancer. Humans, dogs and rabbits get Alzheimer's disease, but rodents do not. Elderly rodents typically die of cancer or kidney disease, but not of cardiovascular disease. In humans, the relative incidence of cancer increases exponentially with age for most cancers, but levels off or may even decline by age 60–75 [3](although colon/rectal cancer continues to increase).[4]

People with the so-called segmental progerias are vulnerable to different sets of diseases. Those with Werner's syndrome suffer from osteoporosis, cataracts, and cardiovascular disease, but not neurodegeneration or Alzheimer's disease; those with Down syndrome suffer type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease, but not high blood pressure, osteoporosis or cataracts. In Bloom syndrome, those afflicted most often die of cancer.

Research[]

Aging (senescence) increases vulnerability to age-associated diseases, whereas genetics determines vulnerability or resistance between species and individuals within species. Some age-related changes (like graying hair) are said to be unrelated to an increase in mortality. But some biogerontologists believe that the same underlying changes that cause graying hair also increase mortality in other organ systems and that understanding the incidence of age-associated disease will advance knowledge of the biology of senescence just as knowledge of childhood diseases advanced knowledge of human development.[5]

Strategies for engineered negligible senescence (SENS) is an emerging research strategy that aims to repair "root causes" for age-related illness and degeneration, as well as develop medical procedures to periodically repair all such damage in the human body, thereby maintaining a youth-like state indefinitely.[6] So far, the SENS programme has identified seven types of aging-related damage, and feasible solutions have been outlined for each. However, critics argue that the SENS agenda is optimistic at best, and that the aging process is too complex and little-understood for SENS to be scientific or implementable in the foreseeable future.[7][8][9] It has been proposed that age-related diseases are mediated by vicious cycles.[10]

On the basis of extensive research, DNA damage has emerged a major culprit in cancer and numerous other diseases related to ageing.[11] DNA damage can initiate the development of cancer or other aging related diseases depending on several factors. These include the type, amount, and location of the DNA damage in the body, the type of cell experiencing the damage and its stage in the cell cycle, and the specific DNA repair processes available to react to the damage.[11]

Diseases[]

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)[]

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is a disease that affects the eyes and can lead to vision loss through break down of the central part of the retina called the macula. Degeneration can occur in one eye or both and can be classified as either wet (neovascular) or dry (atrophic). Wet AMD commonly is caused by blood vessels near the retina that lead to swelling of the macula.[12] The cause of dry AMD is less clear, but it is thought to be partly caused by breakdown of light-sensitive cells and tissue surrounding the macula. A major risk factor for AMD is age over the age of 60.[13]

Alzheimer's disease[]

Alzheimer's disease is classified as a "protein misfolding" disease. Aging causes mutations in protein folding, and as a result causes deposits of abnormal modified proteins accumulate in specific areas of the brain. In Alzheimer's,deposits of Beta-amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau protein form extracellular plaques and extracellular tangles.[14] These deposits are shown to be neurotoxic and cause cognitive impairment due to their initiation of destructive biochemical pathways.[15]

Atherosclerosis[]

Atherosclerosis is categorized as an aging disease and is brought about by vascular remodeling, the accumulation of plaque, and the loss of arterial elasticity. Over time, these processes can stiffen the vasculature. For these reasons, older age is listed as a major risk factor for atherosclerosis.[16] Specifically, the risk of atherosclerosis increases for men above 45 years of age and women above 55 years of age.[17]

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)[]

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a noncancerous enlargement of the prostate gland due to increased growth.[18] An enlarged prostate can result in incomplete or complete blockage of the bladder and interferes with a man's ability to urinate properly. Symptoms include overactive bladder, decreased stream of urine, hesitancy urinating, and incomplete emptying of the bladder.[19][20] By age 40, 10% of men will have signs of BPH and by age 60, this percentage increases by 5 fold. Men over the age of 80 have over a 90% chance of developing BPH and almost 80% of men will develop BPH in their lifetime.[18][21]

Cancer[]

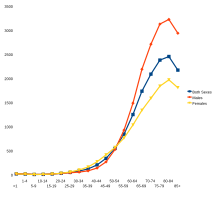

Although it is possible for cancer to strike at any age, most patients with invasive cancer are over 65,[22] and the most significant risk factor for developing cancer is age.[22]According to cancer researcher Robert A. Weinberg, "If we lived long enough, sooner or later we all would get cancer."[23] Some of the association between aging and cancer is attributed to immunosenescence,[24] errors accumulated in DNA over a lifetime[25] and age-related changes in the endocrine system.[26] Aging's effect on cancer is complicated by factors such as DNA damage and inflammation promoting it and factors such as vascular aging and endocrine changes inhibiting it.[27]

Parkinson's disease[]

Parkinson's disease, or simply Parkinson's,[28] is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The disease has many complications, including Dementia, depression, anxiety.[29] Parkinson's disease typically occurs in people over the age of 60, of whom about one percent are affected.[30][31] The prevalence of Parkinson's disease dementia also increases with age, and to a lesser degree, duration of the disease.[32] Exercise in middle age may reduce the risk of PD later in life.[33]

Stroke[]

Stroke was the second most frequent cause of death worldwide in 2011, accounting for 6.2 million deaths (~11% of the total).[34] Stroke could occur at any age, including in childhood, the risk of stroke increases exponentially from 30 years of age, and the cause varies by age.[35] Advanced age is one of the most significant stroke risk factors. 95% of strokes occur in people age 45 and older, and two-thirds of strokes occur in those over the age of 65.[36][37] A person's risk of dying if he or she does have a stroke also increases with age.

See also[]

- Accelerated aging disease

- Alliance for Aging Research

- Gerontology

- Senescence

References[]

- ^ Belikov, Aleksey V. (2019-01-01). "Age-related diseases as vicious cycles". Ageing Research Reviews. 49: 11–26. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2018.11.002. ISSN 1568-1637. PMID 30458244. S2CID 53567141.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aubrey D.N.J, de Grey (2007). "Life Span Extension Research and Public Debate: Societal Considerations" (PDF). Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology. 1 (1, Article 5). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.745. doi:10.2202/1941-6008.1011. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Belikov, Aleksey V. (22 September 2017). "The number of key carcinogenic events can be predicted from cancer incidence". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12170. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712170B. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12448-7. PMC 5610194. PMID 28939880.

- ^ "SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003" (PDF). Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-25. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ^ Hayflick, L (2004). "The not-so-close relationship between biological aging and age-associated pathologies in humans". The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 59 (6): B547–B550. doi:10.1093/gerona/59.6.B547. PMID 15215261.

- ^ "The SENS Platform: An Engineering Approach to Curing Aging". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on June 28, 2008.

- ^ Warner, H; Anderson, J; Austad, S; Bergamini, E; Bredesen, D; Butler, R; Carnes, BA; Clark, BF; et al. (2005). "Science fact and the SENS agenda". EMBO Reports. 6 (11): 1006–8. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400555. PMC 1371037. PMID 16264422.

- ^ De Grey, AD (2005). "Like it or not, life-extension research extends beyond biogerontology". EMBO Reports. 6 (11): 1000. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400565. PMC 1371043. PMID 16264420.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey. "The biogerontology research community's evolving view of SENS". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ Belikov, Aleksey V. (January 2019). "Age-related diseases as vicious cycles". Ageing Research Reviews. 49: 11–26. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2018.11.002. PMID 30458244. S2CID 53567141.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 8;361(15):1475-85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804615. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2009 Nov 5;361(19):1914. PMID: 19812404.

- ^ Zarbin, Marco A. (2004-04-01). "Current Concepts in the Pathogenesis of Age-Related Macular Degeneration". Archives of Ophthalmology. 122 (4): 598–614. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.4.598. ISSN 0003-9950. PMID 15078679.

- ^ "Facts About Age-Related Macular Degeneration | National Eye Institute". nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ Franceschi, Claudio; Garagnani, Paolo; Morsiani, Cristina; Conte, Maria; Santoro, Aurelia; Grignolio, Andrea; Monti, Daniela; Capri, Miriam; Salvioli, Stefano (2018-03-12). "The Continuum of Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Common Mechanisms but Different Rates". Frontiers in Medicine. 5: 61. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00061. ISSN 2296-858X. PMC 5890129. PMID 29662881.

- ^ Bloom, George S. (2014-04-01). "Amyloid-β and Tau: The Trigger and Bullet in Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis". JAMA Neurology. 71 (4): 505–508. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847. ISSN 2168-6149. PMID 24493463.

- ^ Wang Julie C.; Bennett Martin (2012-07-06). "Aging and Atherosclerosis". Circulation Research. 111 (2): 245–259. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388. PMID 22773427.

- ^ "Atherosclerosis | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Prostate Enlargement (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia) | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ "What is Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)? – Urology Care Foundation". www.urologyhealth.org. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) Guideline – American Urological Association". www.auanet.org. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ "Medical Student Curriculum: Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy (BPH) – American Urological Association". www.auanet.org. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Coleman WB, Rubinas TC (2009). "4". In Tsongalis GJ, Coleman WL (eds.). Molecular Pathology: The Molecular Basis of Human Disease. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-12-374419-7.

- ^ Johnson G (28 December 2010). "Unearthing Prehistoric Tumors, and Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017.

- ^ Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Larbi A (August 2010). "Immunosenescence and cancer". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 75 (2): 165–72. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.06.012. PMID 20656212.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. (2002). "The Preventable Causes of Cancer". Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4072-0. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

A certain irreducible background incidence of cancer is to be expected regardless of circumstances: mutations can never be absolutely avoided, because they are an inescapable consequence of fundamental limitations on the accuracy of DNA replication, as discussed in Chapter 5. If a human could live long enough, it is inevitable that at least one of his or her cells would eventually accumulate a set of mutations sufficient for cancer to develop.

- ^ Anisimov VN, Sikora E, Pawelec G (August 2009). "Relationships between cancer and aging: a multilevel approach". Biogerontology. 10 (4): 323–38. doi:10.1007/s10522-008-9209-8. PMID 19156531. S2CID 17412298.

- ^ de Magalhães JP (May 2013). "How ageing processes influence cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 13 (5): 357–65. doi:10.1038/nrc3497. PMID 23612461. S2CID 5726826.

- ^ "Understanding Parkinson's". Parkinson's Foundation. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Sveinbjornsdottir S (October 2016). "The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139 Suppl 1: 318–24. doi:10.1111/jnc.13691. PMID 27401947.

- ^ "Parkinson's Disease Information Page". NINDS. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Carroll WM (2016). International Neurology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 188. ISBN 978-1118777367. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Garcia-Ptacek S, Kramberger MG (September 2016). "Parkinson Disease and Dementia". Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 29 (5): 261–70. doi:10.1177/0891988716654985. PMID 27502301. S2CID 21279235.

- ^ Ahlskog JE (July 2011). "Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease?". Neurology. 77 (3): 288–94. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e318225ab66. PMC 3136051. PMID 21768599.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death". WHO. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02.

- ^ Ellekjaer H, Holmen J, Indredavik B, Terent A (November 1997). "Epidemiology of stroke in Innherred, Norway, 1994 to 1996. Incidence and 30-day case-fatality rate". Stroke. 28 (11): 2180–4. doi:10.1161/01.STR.28.11.2180. PMID 9368561. Archived from the original on February 28, 2008.

- ^ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (1999). "Stroke: Hope Through Research". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2015-10-04.

- ^ Senelick Richard C., Rossi, Peter W., Dougherty, Karla (1994). Living with Stroke: A Guide for Families. Contemporary Books, Chicago. ISBN 978-0-8092-2607-8. OCLC 40856888.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aging-associated diseases. |

- Aging-associated diseases

- Geriatrics

- Senescence