Albert Göring

Albert Göring | |

|---|---|

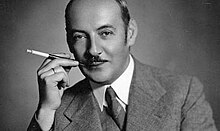

Albert Göring in 1936 | |

| Born | Albert Günther Göring 9 March 1895 |

| Died | 20 December 1966 (aged 71) |

| Resting place | Göring family plot, Munich[1] |

| Nationality | German, Austrian |

| Education | Technical University of Munich |

| Alma mater | Technische Universität München[1] |

| Occupation | Businessman |

| Known for | Anti-Nazi activities |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Elizabeth Göring |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

Albert Günther Göring (9 March 1895 – 20 December 1966) was a German engineer, businessman, and the younger brother of Hermann Göring (the head of the German Luftwaffe and a leading member of the Nazi Party). In contrast to his brother, Albert was opposed to Nazism, and he helped Jews and others who were persecuted in Nazi Germany.[2] He was shunned in post-war Germany because of his family name, and he died without any public recognition and received very little attention for his humanitarian efforts until decades after his death.[3]

Family background[]

Albert Göring was born on 9 March 1895 in the Berlin suburb of Friedenau.[4] He was the fifth child of the former Reichskommissar to German South-West Africa and German Consul General to Haiti, Heinrich Ernst Göring, and his wife Franziska "Fanny" Tiefenbrunn, who came from a Bavarian peasant family.

The Görings were relatives of numerous residents of the Eberle/Eberlin area in Switzerland and Germany, among them German Counts Zeppelin, including aviation pioneer Ferdinand von Zeppelin; German nationalist art historian Herman Grimm, author of the concept of the German hero as a mover of history that was later embraced by the Nazis; Swiss historian of art and cultural, political and social thinker Jacob Burckhardt; Swiss diplomat, historian and President of the International Red Cross Carl J. Burckhardt; the Merck family, owners of the German pharmaceutical giant Merck; and German Catholic writer and poet Gertrud von Le Fort.[5]

The Göring family lived with their children's aristocratic godfather of Jewish heritage, Ritter von Mauternburg, in his Veldenstein and Mauterndorf castles. Epenstein was a prominent physician and acted as a surrogate father to the children as Heinrich Göring was often absent from the family home.[6] Albert was one of five children. His brothers were Hermann and Karl Ernst Göring, and his half-sisters were Olga Therese Sophia and Paula Elisabeth Rosa Göring, both from his father's first marriage.[7]

Epenstein began an affair with Franziska Göring about a year before Albert's birth.[8] A strong physical resemblance between Epenstein and Albert Göring even led many to believe that they were father and son. If this were true, it meant that Albert Göring was one-quarter Jewish.[8] However, Franziska Göring had accompanied her husband to his post in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and lived there with him between March 1893 and mid-1894, which makes this seem extremely unlikely.[9] In 2016, Albert's daughter (Elizabeth) told the BBC that her mother (Mila) said that Albert told her that Epenstein was his father.[10]

During World War I, Albert served in the trenches with the Imperial German army as a signal engineer.[11]

Anti-Nazi activity[]

Göring seemed to have acquired his godfather's character as a bon vivant and looked set to lead an "unremarkable life" as a filmmaker, until the Nazis came to power in 1933. Unlike his elder brother Hermann, who was a leading party member, Albert Göring despised Nazism and the brutality involved.

Many anecdotal stories exist about Göring's resistance to the Nazi ideology and regime.[12] For example, Albert is reported to have joined a group of Jewish women who had been forced to scrub the street. The SS officer in charge inspected his identification, and ordered the group's scrubbing activity to stop after realizing he could be held responsible for allowing Hermann Göring's brother to be publicly humiliated.[13]

Albert Göring used his influence to get his Jewish former boss Oskar Pilzer freed after the Nazis arrested him. Göring then helped Pilzer and his family escape from Germany. He is reported to have done the same for many other German dissidents.[13]

Göring intensified his anti-Nazi activity when he was made export director at the Škoda Works in Czechoslovakia. He encouraged minor acts of sabotage and had contact with the Czech resistance. On many occasions, he forged his brother's signature on transit documents to enable dissidents to escape. When he was caught, he used his brother's influence to gain his release. Göring also sent trucks to Nazi concentration camps with requests for labourers. The trucks would stop in an isolated area, and their passengers were then allowed to escape.[13]

After the war, Albert Göring was questioned during the Nuremberg Tribunal. However, many of those he had helped testified for him, and he was released. Soon afterwards, Göring was arrested by the Czechs, but he was again released when the full extent of his activities became known.[13]

In 2010, Edda Göring, the daughter of Hermann, said of her uncle Albert in The Guardian:

He could certainly help people in need himself financially and with his personal influence, but, as soon as it was necessary to involve higher authority or officials, then he had to have the support of my father, which he did get.[1]

Later life[]

On his release, Göring returned to Germany, but was shunned because of his family name. He found work occasionally as a writer and translator, and he lived in a modest flat far from the baronial splendour of his childhood. In his last years, Göring lived on a pension from the government. He knew that if he married, on his death the pension payments would be transferred to his wife. As a sign of gratitude, he married his housekeeper in 1966 so she would receive his pension. One week later, Albert Göring died without his wartime anti-Nazi activities having been publicly acknowledged.[3]

Although Göring lived out his last years in Munich in Bavaria, he died farther away in a hospital in Neuenbürg in the neighbouring state of Baden-Württemberg.[14]

Reception and popular culture[]

Albert Göring's story remained largely unknown to the public even three decades after his death. While his brother Hermann Göring was the subject of many publications, Albert received little or no attention. One exception was a short article in the German weekly magazine aktuell by the writer Ernst Neubach in the early 1960s when Göring was still alive. At the end of the 20th century and at the beginning of the 21st century, the situation began to change when Albert Göring and his work started to become the subject of several books and documentaries, which in turn triggered a larger number of new publications.

Books[]

The British author James Wyllie published a double biography The Warlord and the Renegade in 2006, which was followed by the book Thirty Four by Australian author William Hastings Burke in 2009. Albert Göring was also covered in the 2011 book Rettungswiderstand (Resistance to save) by the German historian and Holocaust survivor Arno Lustiger.

Göring's humanitarian efforts are recorded by William Hastings Burke in the book Thirty Four (ISBN 9780956371201). A review of the 2009 book in The Jewish Chronicle concluded with a call for Albert Göring to be honoured at the Yad Vashem memorial;[15] however, Yad Vashem subsequently announced that they would not list Göring as Righteous Among the Nations, stating that although "[t]here are indications that Albert Goering had a positive attitude to Jews and that he helped some people," there is not "sufficient proof, i.e., primary sources, showing that he took extraordinary risks to save Jews from danger of deportation and death."[16]

Documentaries[]

Göring was the subject of a couple of film documentaries, the first and most extensive one being The Real Albert Goering, which was produced by 3BM TV and broadcast in the UK in 1998. The documentary, which was later picked up by the History Channel for distribution outside of the UK, made its way overseas to other countries, most notably in America, during the early 2000s.[17] Roughly a decade later William Hastings Burke produced a documentary based on his book and in 2014 Véronique Lhorme's Le Dossier Albert Göring was broadcast on French TV. In January 2016, the German TV channel Das Erste broadcast the docudrama Der gute Göring (The Good Göring) with Barnaby Metschurat as Albert Göring and Francis Fulton-Smith as his brother Hermann.[18]

A BBC Radio 4 documentary entitled The Good Goering, also broadcast in January 2016, featured an investigation of the life of Albert Göring by British journalist and broadcaster Gavin Esler.[10]

See also[]

- Heinz Heydrich, Reinhard Heydrich's younger brother who helped many Jews escape the Nazis.

- List of Germans who resisted Nazism

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c William Hastings Burke, 'Albert Göring, Hermann's anti-Nazi brother' in The Guardian dated 20 February 2010 online at guardian.co.uk, accessed 12 December 2012

- ^ Wyllie 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burke, pp. 205–214.

- ^ Burke 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Paul 1983, p. 33.

- ^ cf. Christian H. Freitag: Ritter, Reichsmarschall & Revoluzzer. Aus der Geschichte eines Berliner Landhauses. Berlin 2015, pp. 25–45.

- ^ Brandenburg 1935, p. not cited.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mosley 1974, p. not cited.

- ^ Burke 2009, pp. 26, 27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gavin, Esler (27 January 2016). "The Good Goering". Seriously. BBC. Radio 4. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Did Hermann Goering's brother save innocent lives from the Nazis?". British Broadcasting Company.

- ^ Goldgar 2000, p. not cited.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bülow 2007, p. not cited.

- ^ Alexander Heilemann: Spur des „guten Göring“ in Neuenbürg. Pforzheimer Zeitung, 16 January 2016 (preview on the newspaper's webseite) (German)

- ^ Sher, Gilead. "Review: Thirty Four". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ^ Top Israeli honor eludes Goering’s brother, who heroically saved Jews, by Stuart Winer and Sue Surkes, in the Times of Israel; published January 25, 2016; retrieved September 20, 2016

- ^ Rabinowitz, Dorothy (28 February 2000). "The Good Brother". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "The Good Goering". BBC Radio 4.

References[]

- Brandenburg, Erich (1995) [1935]. Die Nachkommen Karls des Grossen (in German). Neustadt an der Aisch; Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Degener. ISBN 3-7686-5102-9. OCLC 34581384.

- Bülow, Louis (2007–2009). "The Good Brother, A True Story of Courage". The Holocaust Project. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- Burke, William Hastings (2009). Thirty Four. London: Wolfgeist Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-9563712-0-1.

- Freitag, Christian H. (2015). Ritter, Reichsmarschall & Revoluzzer. Aus der Geschichte eines Berliner Landhauses. Berlin. p. 25–45. ISBN 978-3-9816130-2-5.

- Goldgar, Vida (2000-03-10). "The Goering Who Saved Jews". Jewish Times (Atlanta). Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- Mosley, Leonard (1974). The Reich Marshal: A biography of Hermann Göring. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04961-7.

- Paul, Wolfgang (1983). Wer war Hermann Göring: Biographie (in German). Esslingen am Neckar: Verlag Bechtle. ISBN 3-7628-0427-3.

- Wyllie, James (2006). The Warlord and the Renegade; The Story of Hermann and Albert Goering. Sutton Publishing Limited. p. 7. ISBN 0-7509-4025-5.

- "The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names (DB Search)". Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

External links[]

Media related to Albert Göring at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Albert Göring at Wikimedia Commons- The Holocaust, Crimes, Heroes, and Victims – Detailed information about Göring's actions and the activities of other Holocaust heroes.

- 1895 births

- 1966 deaths

- German anti-fascists

- German resistance members

- German humanitarians

- People who rescued Jews during the Holocaust

- Engineers from Berlin

- Göring family

- 20th-century German businesspeople

- German military personnel of World War I

- People from Tempelhof-Schöneberg

- Nazi personnel who resisted the Holocaust