Aldo Busi

Aldo Busi | |

|---|---|

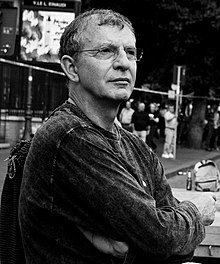

Busi in 2008 | |

| Born | February 25, 1948 Montichiari (Brescia) |

| Occupation | Novelist, translator |

| Language | Italian |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Citizenship | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Verona |

| Period | 1984-present |

| Literary movement | Postmodernism |

| Notable works | Seminar on Youth The Standard Life of a Temporary Pantyhose Salesman Sodomies in Elevenpoint |

| Notable awards | Premio Mondello 1984, Premio Frignano 2002, Premio Boccaccio 2013. |

Aldo Busi (born 25 February 1948) is a contemporary Italian writer and translator, famous for his linguistic invention and for his polemic force as well as for some prestigious translations from English, German and ancient Italian that include Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Lewis Carroll, Christina Stead, Giovanni Boccaccio, Baldesar Castiglione, Friedrich Schiller, Joe Ackerley, John Ashbery, Heimito von Doderer, Ruzante, Meg Wolitzer, Paul Bailey, Nathaniel Hawthorne.[1]

Biography[]

Early years: youth and literary training[]

He was born in Montichiari, near Brescia in Lombardy.

Third son of Marcello Busi (1913 – 1982) and Maria Bonora (1914 – 2008) he is raised in poverty conditions with his father, mother and siblings getting noticed for his predisposition to writing (according to the writer himself already since he attended the third year of elementary school his essays were awaited). At 14 years he's obliged by his father, manager of a tavern, to leave school and he begins to work as a waiter in several locations in the Lake Garda area. He then transfers to Milan and in 1968 he wins the exemption from the military service thanks to the article 28/a that waives self-proclaimed homosexuals. He decides after to live abroad, first in France between 1969 and 1970 (Lille and then Paris), then in Britain (London between 1970 and 1971), Germany (Munich, 1971 and 1972, Berlin in 1974), Spain (Barcelona in 1973) and in the US (New York, in 1976) working as waiter, sweeper, night porter or kitchen boy. He therefore learns several languages (French, English, German, Spanish) and keeps on revising Il Monoclino (his debut book that in 1984 will be published with the definitive title of ).[2] Back in Italy he works occasionally as an interpreter (experience that will be at the basis of his second novel [3] and he engages in his first translations from English and German. In the meantime he gets a G.E.D. in Florence in 1976 and in 1981 he graduates in Foreign Languages and Literatures at Università di Verona, with a thesis on the American poet John Ashbery. Of Ashbery in 1983 Busi will translate Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror that will eventually win the prestigious Accademia dei Lincei prize.[4] Among Busi's spiritual fathers appear Laurence Sterne, Gustave Flaubert, Arthur Rimbaud, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Miguel de Cervantes and Marcel Proust.[5]

Maturity and success: the novelist, the essayist, the translator[]

Busi puts the novel to the center of his production (he wrote seven) as he considers it to be the highest form of literature for structure complexity, aesthetic contents and expressive flexibility. Close observer of society and customs, particularly Italian ones, his characters reflect a deep psychological insight, and their fictional context is outlined with vivid impressionistic realism.[6]

Left-wing, feminist and political militant for homosexual rights, fervently anticlerical in his life and in his art, he published a serie of five «end-of-millennium» essays and six manuals «for a perfect humanity» that analyse contemporary socio-political issues and propose some guidelines to handle them in daily life. Because of his open stances and his straightforward language and depictions, he finds himself to be often in the middle of given and received lawsuits. Particular attention wins in 1990 the case of his fourth book , that receives a large media coverage but for which he is fully absolved.[7] It will only be the parent of his legal proceedings, because the same fate will affect several of his future works, magazines and newspapers articles, and TV appearances.[8]

His extensive literary production includes also seven travel books (among which ),[9] two novellas, a collection of stories, two fables, a theatre play, a screenplay, two song books and two self-portraits. Indefatigable traveller, his reports from the five continents also consistently contribute to his fame as a valued narrator and observer.[10] He occasionally writes also for newspapers and magazines.

His personal research as a scholar of languages and as a translator from foreign languages leads him to also translate some works of the Italian Middle Ages and Renaissance from ancient to modern Italian, such as Boccaccio's The Decameron, Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier (with Carmen Covito), Ruzante, and The Novellino by anonymous author of the 13th century (with Carmen Covito). According to Busi, nowadays several classics of Italian literature, including Divine Comedy, are more known abroad than in Italy, because language update hasn't yet become a customary on the Italian literary scene. His translation of The Decameron was awarded in 2013 with the Premio Letterario Boccaccio.[11] Following the same philosophy of language update, between 1995 and 2008 Busi directs for the publisher Frassinelli a book serie of some classics from the most important modern literatures, that proposes new translations which use all the linguistic registers of contemporary language. Between 2004 and 2009 he also has the TV serie on Literature Amici libri (trans. "Book friends") inside a talent show, where he also plays the role of teacher of General Education.[12]

In 2006 the literary critic Marco Cavalli writes the first monograph on Aldo Busi titled Busi in corpo 11, where he describes, analyses and comments the whole writer's work.

The immobility of Italy and the «writing strike»[]

Around half of the 2000s the writer declares to be tired and disappointed by the immobility of culture and politics of his own country. He claims also that his work has been boycotted by Italy and decides to withdraw from writing, at least from organic novel writing.[13] In the following years, therefore, his releases are much more sporadic then before, and limited to some minor works and to the revision of old material. The only exception is represented by the novel El especialista de Barcelona, that according to him is totally unexpected to the writer himself, and that, not for nothing, talks also about a writer's tackling against a book that wants to be written.[14]

Works[]

Novels[]

- (Seminario sulla gioventù), translated by Stuart Hood, London, Faber and Faber, 1989, ISBN 0571152899

- (Vita standard di un venditore provvisorio di collant), translated by Raymond Rosenthal, New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988; London, Faber and Faber, 1990, ISBN 0374528195

- La delfina bizantina, Milan, Mondadori, 1986.

- Vendita galline Km 2, Milan, Mondadori, 1993.

- Suicidi dovuti, Milan, Frassinelli, 1996.

- Casanova di se stessi, Milan, Mondadori, 2000.

- El especialista de Barcelona, Milan, Dalai Editore, 2012.

Travel Proses[]

- (Sodomie in corpo 11), translated by Stuart Hood, London, Faber and Faber, 1992, ISBN 0571142052

- (Altri abusi), translated by Stuart Hood, London, Faber and Faber, 1997, ISBN 0571179053

- Cazzi e canguri (pochissimi i canguri), Milan, Frassinelli, 1994.

- Aloha!!!!! (gli uomini, le donne e le Hawaii), Milan, Bompiani, 1998.

- La camicia di Hanta, Milan, Mondadori, 2003.

- E io, che ho le rose fiorite anche d'inverno?, Milan, Mondadori, 2004.

- Bisogna avere i coglioni per prenderlo nel culo, Milan, Mondadori, 2006.

Manuals «for a Perfect Humanity»[]

- Manuale del perfetto Gentilomo, Milan, Sperling & Kupfer, 1992.

- Manuale della perfetta Gentildonna, Milan, Sperling & Kupfer, 1994.

- Nudo di madre, Milan, Bompiani, 1997.

- Manuale della perfetta mamma, Milan, Mondadori, 2000.

- Manuale del perfetto papà, Milan, Mondadori, 2001.

- Manuale del perfetto single, Milan, Mondadori, 2002.

Other Writings[]

- Pâté d'homme (play), Milan, Mondadori, 1989.

- L'amore è una budella gentile (short novel), Milan, Leonardo, 1991.

- Sentire le donne (collection of stories), Milan, Bompiani, 1991.

- Le persone normali (essay), Milan, Mondadori, 1992.

- Madre Asdrubala (fable), Milan, Mondadori, 1995.

- La vergine Alatiel (screenplay), Milan, Mondadori, 1996.

- L'amore trasparente. Canzoniere (song book), Milan, Mondadori, 1997.

- Per un'Apocalisse più svelta (essay), Milan, Bompiani, 1999.

- Un cuore di troppo (short novel), Milan, Mondadori, 2001.

- La signorina Gentilin dell'omonima cartoleria (short novel), Milan, Oscar Mondadori, 2002.

- Guancia di tulipano (fable), Milan, Oscar Mondadori, 2003.

- Aaa! (collection of stories), Milan, Bompiani, 2010.

- E baci (essay), Rome, Editoriale Il Fatto, 2013.

- Vacche amiche (self-portrayal), Venice, Marsilio Editore, 2015.

- L'altra mammella delle vacche amiche (self-portrayal), Venice, Marsilio Editore, 2015.

- Le consapevolezze ultime (essay), Turin, Einaudi, 2018.

Bibliography[]

(in Italian)

- Marco Cavalli (a cura di), Dritte per l'aspirante artista (televisivo): Aldo Busi fa lezione ad Amici, Milan, Feltrinelli, 2005, ISBN 8804539259

(in Italian)

- Marco Cavalli, Busi in corpo 11: miracoli e misfatti, opere e opinioni, lettere e sentenze, Milan, Il Saggiatore, 2006, ISBN 8842812129

(in Italian)

- Marco Cavalli, Aldo Busi, Florence, Cadmo, 2007, ISBN 8879233653

References[]

- ^ See (in Italian) M.Cavalli, Aldo Busi, Florence, Cadmo, 2007.

- ^ Read a New York Times article about Seminar on Youth [1]

- ^ Read a New York Times article about The Standard Life of a Temporary Pantyhose Salesman[2]

- ^ Read (in Italian) M. Cavalli, Aldo Busi, Florence, Cadmo, 2007

- ^ An interview on www.italialibri.net (in Italian)[3]

- ^ Read (in Italian) M. Cavalli, Busi in corpo 11, Milan, Il Saggiatore, 2006

- ^ An article about the trial from the newspaper la Repubblica (in Italian)[4]

- ^ Read (in Italian) M. Cavalli, Busi in corpo 11, Milan, Il Saggiatore, 2006

- ^ See a The Independent article on Uses and Abuses [5]

- ^ For an analysis on his works see the monograph (in Italian) M. Cavalli, Busi in corpo 11, Milan, Il Saggiatore, 2006

- ^ Interview to Aldo Busi on translation, on the occasion of the Premio Letterario Boccaccio prize-awarding (in Italian) [6]

- ^ A transcript of some of these lessons can be found in (in Italian) M. Cavalli (a cura di), Dritte per l'aspirante artista (televisivo): Aldo Busi fa lezione ad Amici, Milan, Feltrinelli, 2005.

- ^ See an article on the newspaper Corriere della sera (in Italian) [7]

- ^ See article on the newspaperla Repubblica (in Italian) [8]

External links[]

- Works by or about Aldo Busi in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- (in Italian) Italialibri:Aldo Busi

- (in Italian)

Newspaper article 24-05-2015 [9]

- 1948 births

- Living people

- Writers from the Province of Brescia

- Italian male writers

- Gay writers

- Italian translators

- LGBT writers from Italy

- Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe