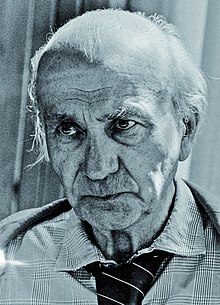

Gyula Illyés

Illyés Gyula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 November 1902 Sárszentlőrinc, Tolna County |

| Died | 15 April 1983 (aged 80) Budapest |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Spouse | Irma Juvancz (married 1931) Flóra Kozmutza (married 1939) |

| Relatives | Father: János Illés Mother: Ida Kálley Daughter: Maria |

Gyula Illyés (2 November 1902 – 15 April 1983) was a Hungarian poet and novelist. He was one of the so-called népi ("from the people") writers, named so because they aimed to show – propelled by strong sociological interest and left-wing convictions – the disadvantageous conditions of their native land.

Early life[]

He was born the son of János Illés (1870 – 1931) and Ida Kállay (1878 – 1931) in Tolna County. His father belonged to a rich gentry family, but his mother came from the most deprived segment of society, agricultural servants.[1] He was their third child and spent his first nine years at his birthplace, where he finished his primary school years (1908 – 1912) and when his family moved to Simontornya, he continued his education at grammar schools there and Dombóvár (1913 – 1914) and Bonyhád (1914 – 1916). In 1926 his parents separated, and he moved to the capital with his mother. He continued senior high school at the Budapest Munkácsy Mihály street gimnazium (1916 – 1917) and at the Izabella Street Kereskedelmi school (1917 – 1921). In 1921 he graduated. From 1918 to 1919 he took part in various left-wing students and youth workers' movements, being present at an attack on Romanian forces in Szolnok during the Hungarian Republic of Councils. On 22 December 1920 his first poem was published (El ne essél, testvér) anonymously in the Social Democrat daily Népszava.

University years[]

He began studies at the Budapest University's department of languages studying Hungarian and French. Due to illegal political activities he was forced to escape to Vienna in December that year, moving on to Berlin and the Rhineland in 1922.

Illyés arrived in Paris in April that year. He did numerous jobs including as a bookbinder. For a while he studied at the Sorbonne and published his first articles and translations in 1923. He became friends with the French surrealists, among them Paul Éluard, Tristan Tzara and René Crevel (each visited him later in Hungary).

Illyés returned to homeland in 1926 following an amnesty. His main forums of activity became and , periodicals edited by the avant-garde writer and poet Lajos Kassák.

Early career[]

Illyés worked for the from 1927 to 1936, and after its bankruptcy he became press referent to the Hungarian National Bank on French agricultural matters (1937 – 1944).

His first critical writing appeared in November 1927 in the review Nyugat ("Occident") – the most distinguished literary magazine of the time –which from 1928 regularly featured his articles and poems. His first book (Nehéz Föld) was also published by Nyugat in 1928.

He made friends with Attila József, László Németh, Lőrinc Szabó , János Kodolányi and Péter Veres, at the time the leading talents of his generation.

In 1931 he married his first wife, Irma Juvancz, a physical education teacher, whom he later divorced.

Illyés was invited to the Soviet Union in 1934 to take part in the 1st Congress of the Soviet Writers' Union where he met André Malraux and Boris Pasternak. From that year he also participated in the editorial work of the review Válasz (Argument), the forum of the young "népi" writers.

He was one of the founding members of the (1937 – 1939), a left-wing and anti-fascist movement. Subsequently, he was invited to the editorial board of Nyugat and became a close friend of its editor, the post-symbolist poet and writer Mihály Babits.

War years[]

During World War II, Illyés was nominated editor-in-chief of Nyugat following the death of Mihály Babits. Having been refused by the authorities to use the name Nyugat for the magazine, he continued to publish the review under a different title: Magyar Csillag ("Hungarian Star").

In 1939 he married Flóra Kozmuta, with whom he had a daughter, Mária.

After the Nazi invasion of Hungary in March 1944, Illyés had to go into hiding along with László Németh, both being labelled anti-Nazi intellectuals.

After World War II[]

He became a member of the parliament of Hungary in 1945, and one of the leaders of the left-wing National Peasant Party. He withdrew from public life in 1947 as the communist takeover of government was approaching. He was a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences from 1945 to 1949. He directed and edited the review from 1946 to 1949.

Although Gyula lived a reclusive life in Tihany and Budapest until the early 1960s, his poetry, prose, theater plays and essays continued to impact Hungarian public and literary life.

On 2 November 1956 he published his famous poem of the Hungarian revolution of 1956, which was not allowed to be republished in Hungary until 1986: "One sentence on tyranny" is a long poem written in 1950.

From the early 1960s he continued to express political, social and moral issues all through his work, but the main themes of his poetry remain love, life and death. Active until his death in April 1983, he published poems, dramas, essays and parts of his diary. His work as a translator is also considerable.

He translated from many languages, French being the most important, but – with the help of rough translations – his volume of translations from the ancient Chinese classics remains a milestone.

Works[]

In his poetry, Illyés was a spokesman for the oppressed peasant class. Typical is "People of the puszta", A puszták népe, 1936. His later work is marked by a more open universality, as well as an appeal for national and individual liberty.

Selection of works[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (July 2010) |

Poetry[]

- Nehéz föld (1928)

- Sarjúrendek (1931)

- Három öreg (1932)

- Hősökről beszélek (1933)

- Ifjúság (1934)

- Szálló egek alatt (1935)

- Rend a romokban (1937)

- Külön világban (1939)

- Egy év (1945)

- Szembenézve (1947)

- Két kéz (1950)

- Kézfogások (1956)

- Új versek (1961)

- Dőlt vitorla (1965)

- Fekete-fehér (1968)

- Minden lehet (1973)

- Különös testamentum (1977)

- Közügy (1981)

- Táviratok (1982)

- A Semmi közelit (2008صصصصصصصىزززد)

Prose[]

- Oroszország (1934)

- Petőfi (1936)

- Puszták népe (1936)

- Magyarok (1938)

- Ki a magyar? (1939)

- Lélek és kenyér (1939)

- Csizma az asztalon (1941)

- Kora tavasz (1941)

- Mint a darvak (1942)

- Hunok Párisban (1946)

- Franciaországi változatok (1947)

- Hetvenhét magyar népmese (1953)

- Balaton (1962)

- Ebéd a kastélyban (1962)

- Petőfi Sándor (1963)

- Ingyen lakoma (1964)

- Szives kalauz (1966)

- Kháron ladikján (1969)

- Hajszálgyökerek (1971)

- Beatrice apródjai (1979)

- Naplójegyzetek, 1–8 (1987–1995)

Theater[]

- A tü foka (1944)

- Lélekbúvár (1948)

- Ozorai példa (1952)

- Fáklyaláng (1953)

- Dózsa György (1956)

- Kegyenc (1963)

- Különc (1963)

- Tiszták (1971)

His work in English translation[]

- A Tribute to Gyula Illyés, Occidental Press, Washington (1968)

- Selected Poems (Thomas Kabdebo and Paul Tabori) Chatto and Windus, London (1971)

- People of the Puszta, Translated and afterword by G.F. Cushing, Chatto and Windus, London (1967), Corvina, Budapest (1967)

- Petőfi, Translated by G.F. Cushing, Corvina, Budapest

- Once Upon a Time, Forty Hungarian Folk Tales, Corvina, Budapest (1970)

- The Tree that Reached the Sky (for children), Corvina, Budapest (1988)

- The Prince and his Magic Horse (for children), Corvina, Budapest (1987)

- 29 poems, Translated by Tótfalusi István, Maecenas, Budapest (1996)

- What You Have Almost Forgotten (Trans. foreword and ed. Willam Jay Smith with Gyula Kodolányi) Kortárs, Budapest (1999)

- Charon's Ferry, Fifty Poems (Translated by Bruce Berlind) Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois (2000)

In anthologies and periodicals[]

- Poems for the Millennium, (ed. Jerome Rothenberg) 2000

- Arion, essays and poems, several issues

- The New Hungarian Quarterly and the Hungarian Quarterly, several issues

- Icarus 6 (Huns in Paris, trans. by Thomas Mark)

- Homeland in the Heights (ed. Bertha Csilla, An anthology of Post-World War II. Hungarian Poetry, Budapest (2000)

References[]

- ^ Judit Frigyesi (2000) Béla Bartók and turn-of-the-century. Budapest, University of California Press. p. 47

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gyula Illyés. |

- Illyés in Hunlit, the on-line multilingual database of Hungarian Book Foundation on Hungarian literature

- Bibliographical Handbook of Hungarian Authors by Albert Tezla; online var. Orig. vers. published at The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS, 1970

- CityPoem 'A Sentence about Tyranny' by Gyula Illyés at Erasmuspc, network for cities and culture

- 1902 births

- 1983 deaths

- People from Tolna County

- Hungarian Roman Catholics

- National Peasant Party (Hungary) politicians

- Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1945–1947)

- Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1947–1949)

- Hungarian male poets

- Members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

- 20th-century Hungarian poets

- Herder Prize recipients

- 20th-century Hungarian male writers

- Baumgarten Prize winners