Alexander Worthy Clerk

Alexander Worthy Clerk | |

|---|---|

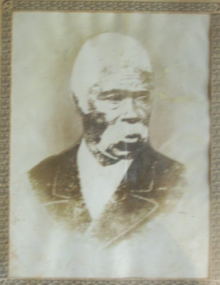

Portrait of Alexander Worthy Clerk | |

| Born | 4 March 1820 |

| Died | 11 February 1906 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | |

| Education | Fairfield Teachers' Seminary |

| Occupation | |

| Spouse(s) | Pauline Hesse (m. 1848) |

| Children | 12, including Nicholas |

| Relatives |

|

| Church | |

| Ordained |

|

Offices held | 1st Deacon, Christ Presbyterian Church, Akropong |

Alexander Worthy Clerk (4 March 1820[1][2][3] – 11 February 1906[4][5][6]) was a Jamaican Moravian pioneer missionary, teacher and clergyman who arrived in 1843 in the Danish Protectorate of Christiansborg, now Osu in Accra, Ghana, then known as the Gold Coast.[7][8][9] He was part of the first group of 24 West Indian missionaries from Jamaica and Antigua who worked under the aegis of the Basel Evangelical Missionary Society of Switzerland.[10][11][12] Caribbean missionary activity in Africa fit into the broader "Atlantic Missionary Movement" of the diaspora between the 1780s and the 1920s.[1][13][14] Shortly after his arrival in Ghana, the mission appointed Clerk as the first Deacon of the Christ Presbyterian Church, Akropong, founded by the first Basel missionary survivor on the Gold Coast, Andreas Riis in 1835, as the organisation's first Protestant church in the country.[13] Alexander Clerk is widely acknowledged and regarded as one of the pioneers of the precursor to the Presbyterian Church of Ghana. As a leader in education in colonial Ghana, he co-established with fellow educators, George Peter Thompson and Catherine Mulgrave, an all-male boarding middle school, the Salem School at Osu in 1843.[15] In 1848, Clerk was an inaugural faculty member at the Basel Mission Seminary, Akropong, now known as the Presbyterian College of Education, where he was an instructor in Biblical studies.[13] The Basel missionaries founded the Akropong seminary and normal school to train teacher-catechists in service of the mission.[13][16] The college is the second oldest higher educational institution in early modern West Africa after Fourah Bay College in Freetown, Sierra Leone which was established in 1827.[16] Clerk was the father of Nicholas Timothy Clerk (1862 – 1961), a Basel-trained theologian, who was elected the first Synod Clerk of the Presbyterian Church of the Gold Coast from 1918 to 1932[7] and co-founded the all boys’ boarding high school, the Presbyterian Boys’ Secondary School established in 1938.[17] A. W. Clerk was also the progenitor of the historically important Clerk family from the suburb of Osu in Accra.[18]

Early life and education[]

Clerk was born on 4 March 1820 on Fairfield Plantage near Spur Tree, Manchester Parish under British colonial rule.[1][19] Little is known of Clerk's parentage and childhood other than his parents were Jamaican Christians.[4] He was the third son among five brothers and four sisters. In 1833, when Alexander Clerk was about thirteen years old, the "apprenticeship act", granting immediate and full freedom to children six years of age and younger, and an intermediate status for those older, was enacted.[1] Between 1838 and 1842, Clerk studied Christian theology, ministry, dogmatics and homiletics; philosophy and ethics; pedagogy and education at the now defunct Fairfield Teachers’ Seminary (Lehrerseminar Fairfield), a teacher's training college and theological seminary, founded in 1837 by the Rev. Jacob Zorn (1803 – 1843), a German-speaking Danish subject and a superintendent of the Moravian Church in Jamaica and the Cayman Islands from 1834 until his death in 1843.[20][21][22] Zorn was also a missionary of the London-based Missions of the Church of the United Brethren and its sister organisation, The Brethren’s Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel.[10][23][24][25][20][26][21] The Jamaican branch of the Moravian Church, which had its early beginnings in 1754, had by then been in the West Indies for nearly hundred years.[13] The first Moravian missionaries in Jamaica were Zecharias Georg Caries, Thomas Shallcross and Gottlieb Haberecht, who evangelised to slaves on the Bogue Estate and later, to surrounding plantations.[27] As part of his classical education, Clerk also studied languages: German, Latin, Greek and Hebrew. The training institute was established by Zorn at the behest of the Moravian mission leadership to prepare young Jamaican men for Christian evangelism, catechism and the propagation of the Gospel in the West Indies after the abolishment of slavery in the British Empire in 1834[10][23] followed by the full emancipation of slaves in Jamaica on 1 August 1838, a little over a year after Queen Victoria's ascension to the throne.[28] Zorn also envisioned sending graduates from his small missionary training school to evangelical mission in Africa.[21] Clerk was also mentored by the Rev. J. Blandfield at the Moravian school. Clerk's education was funded by a wealthy Victorian Christian woman from Bath, Somerset, Mrs. P. Skeate (née Ibbett) .[25][20][26] A. W. Clerk maintained correspondence with his English benefactor when he later worked on the Gold Coast as a teacher-missionary.[26] Clerk was set to become a teacher-catechist and a missionary affiliated to the Fairfield Moravian Church mission presbytery or classis, (founded on 1 January 1826) after his graduation from the seminary and subsequent consecration in 1842.[10][29][30]

Missionary activities on the Gold Coast[]

Historical context[]

Early accounts indicate that the Moravian Church in Herrnhut in Saxony, Germany, recruited an inhabitant of the Gold Coast in 1735 and trained him in the arts and philosophy at the University of Copenhagen.[11] However, on his return to the Gold Coast, the man found out that he could barely speak his mother tongue.[11] A series of European missions were embarked upon by these Protestant missionary bodies, including the Dutch Missionary Society, North German Missionary Society, Baptist Missionary Society and the Church Missionary Society.[31] Some missionaries died within a few years, others within a few months.[10] The Directors of the Danish Guinea Company invited Missions of the Church of the United Brethren, a missionary society of the Moravian Church to the Gold Coast, to teach at the castle and fort schools with five missionaries arriving at Christiansborg in 1768.[31] The first two batches of eleven missionaries all died within a short period from tropical diseases such as malaria, blackwater fever, yellow fever and dysentery, having not fully acclimatised to the local environment.[31][32][33] European missionaries who operated in the Caribbean, Latin America and Southeast Asia were also infected with dengue fever. A group of Christian Protestants from the Lutheran Moravians and other sister Reformed Churches in Germany and Switzerland founded the German Missionary Society in 1815 as "the result of a pledge taken by a few dedicated Christians at Basel in the face of a military threat."[34][35][36] "If God would spare their city, they pledged to begin a seminary for the training of missionaries," the Christian believers asserted.[35] The mission later changed its name to the Basel Evangelical Missionary Society, and finally the Basel Mission.[34] This German Missionary Society had roots in the Deutsche Christentumgesellschaft, established in Basel in 1780 as a Bible reading fellowship that sought to disseminate Christian literature.[13] They envisioned working with established missionary societies already operating in "unevangelized areas" in the world.[34]

In 1825, the Governor of the Danish Protectorate, Christiansborg (Osu), Major Johan Christopher von Richelieu, upon the observation of the degradation of moral values of European residents living within and without the Danish fort, Christiansborg Castle, requested the Danish Crown, through the Rev. Bone Falck Rønne (1764–1833), founder and board chair of the Danish Missionary Society (established on 17 June 1821), who represented Basel Mission interests in Denmark, to arrange for missionaries from the Basel Evangelical Missionary Society in Switzerland to evangelize in the then Gold Coast colony.[11][37][38][39]For a decade and half, the chaplain's station at the Christiansborg Castle had remained vacant.[37] Richelieu acted as a chaplain and reinstated public Christian worship, set up a school where 150 pupils were baptised and educated. More hands were therefore needed for evangelism.[37][40] In March 1827, four young men from rural Switzerland and southern Germany between the ages of 23 and 27 years were selected by the Basel Mission. They were: Karl F. Salbach (27 years), Gottlieb Holzwath (26 years), Johannes Henke (23 years) and the Swiss-born Johannes Gottlieb Schmidt (24 years).[11][37][41] They were skilled tradesmen with practical training experience in pottery, carpentry, shoe-making, masonry, joinery hat-making and black-smithing.[40]

In Christiansborg, Accra, they also started the Basel Mission Trading Factory to export palm oil and other local products to fund the mission work and also set up an artisan workshop to train local entrepreneurs in advanced methods of tradesmanship in order to serve their communities on the Gold Coast and in West Africa, which in the view of the Basel committee, was a way of atoning for the horror and devastating effects of the slave trade brought on by European colonialism.[40] According to church history, their priorities were "to become acclimatised, to take time over the selection of a permanent site for the mission, to master the local language at all costs, to begin actual mission activity by founding a school, and lastly to present the Gospel with love and patience...to show to the people an inexhaustible forbearance and an excess of beneficent love, even though only a few of the thousand bleeding wounds may be healed which greed of gain and the cruel craftiness of the European have caused."[41]

They arrived in Christiansborg on 18 December 1828 and had their first church service at a coastal hamlet called Amanfon, near Osu on 28 December 1828. All but Johannes Henke died within eight months of their arrival (August 1829) from malaria and other tropical diseases.[11] Henke eventually died on 22 November 1831.[11] On 21 March 1832, a second batch of three missionaries made up of the Rev. Andreas Riis, the Rev. Peter Peterson Jager and Dr. Christian Frederich Heinze, a physician arrived to continue the work.[42] Five weeks after their arrival, the medical doctor who was supposed to take care of the health needs of the other two missionaries died of malaria on 26 April 1832. The Rev. P. P. Jager also died on 18 July 1832.[11]

The Rev. Andreas Riis, a Danish minister was the only surviving missionary. After becoming ill from malaria fever, a native herbalist, introduced to Riis by his Euro-African trader friend and a friend of the mission, George Lutterodt, treated him with lemon, soap, a cold bath and naturally occurring quinine in tree bark. After his recovery, Lutterodt advised Riis to move to the hilly countryside in Akropong – Akuapem where the climate is much cooler and had a more conducive environment.[11]

In January 1835, Riis and his friend were warmly received by the then Omanhene of Akuapem, Nana Addo Dankwa I. They finally moved and settled at Akropong on 26 March 1835. Osiadan, meaning "builder in the Akan language, is what Riis was affectionately called, because he had built his house made of stones and timber.[10] He ate local foods and spoke Akuapem Twi just like the people of Akropong. Riis lived like the locals at the time, residing in the forested hinterlands, using palm branches as sleeping mats and eating regional delicacies like peppersoup, snails and wormfish by some accounts.[10]

After settling for a year and with the approval of the Home Committee of the Basel Mission, Riis arranged to get a wife called Anna Margaretha Wolters, a twenty year old Danish lady. Among those who came with her were Andreas Stranger and Johannes Murdter.[11][43] Stranger died on Christmas Eve in 1837 and Riis’ own infant died at the close of 1838. Riis had become the symbol of hope for the evangelical revival in the missionary work.[11]

Riis’ poor health condition, the rough terrain and the high death rates of European missionaries, sometimes reaching eighty percent, coupled with the failure of the missionary work compelled the Basel Missionary Society to abandon the work and recall Riis.[10][36] For eight years, Riis had been unable to convert a native to Christianity and could not boast of a single baptism.[10] In 1840, Andreas Riis travelled through Akwamu, Shai, Kroboland, Akim Abuakwa, and Cape Coast and arrived in Kumasi in 1840.[11] Seeing that conditions were too harsh to contain, the Basel Mission authorities were displeased and Riis was recalled to Switzerland - the mission was to be closed.[10] At the valedictory durbar organised in honour of Riis, the paramount chief, Omanhene of Akuapem, is known to have remarked, "When God created the world, He made the Book (Bible) for the European and animism (fetish) for the African, but if you could show us some Africans who could read the Bible, then we would surely follow you".[10][11]

Arrival of West Indian missionaries[]

This chief's coded message gave Riis and the Basel Mission Society food for thought. The dawn of a new day for African missions appeared when contacts were made to involve Afro-Caribbean Christians from the West Indies in the mission to Africa. Already, such a suggestion had come to Basel from England, but the impetus for Basel's involvement must have come from Riis.[10]

Riis arrived at the European headquarters of the Basel Mission on 7 July 1840 and immediately conferred with the directors of the mission who had already decided to end the mission's operations in West Africa.[34] Riis then made a compelling case by narrating the Akropong's chief farewell address to the mission's board committee.[34] The directors agreed to go to the Caribbean islands with the aim of finding the descendants of freed slaves who were perhaps better suited or adapted to acclimatise to the West African tropical environment, which had a similar climate to the West Indies.[34] Morally, they were well-equipped to handle missionary work due to their strong sense of social mission, gleaned from the abolitionist and emancipation movements, and an imbibing of the Moravian Christian educational ethos in the West Indies.[13] Furthermore, the Afro-Caribbean recruits had no immediate links to families or clans or ethnic groups in Africa which made them neutral agents in evangelical efforts.[13]

Sometime in 1842, the Home Committee selected new missionary graduate, the Rev. Johann Georg Widmann (1814 – 1876), the assistant missionary, Hermann Halleur and the Beuggen and Basel-trained Americo-Liberian mission teacher, George Peter Thompson (1819 – 1889) to go to Jamaica to recruit Christians of African descent.[34][44][13][21] On 28 May 1842, Andreas Riis and his wife, Anna Wolters, Widmann together with Thompson left Basel for the British leeward island of Antigua in the West Indies via Gravesend and Liverpool to engage and recruit black Christian men who would accompany them to West Africa while Halleur went directly to the Gold Coast to prepare the grounds for their arrival.[34] With the assistance of James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, the Governor of Jamaica at the time, the Rev. Jacob Zorn, the Superintendent of the Moravian Mission in Jamaica, the Rev. Jacob F. Sessing and the Rev. J. Miller, an agent of the Africa Civilization Society, Riis was able to recruit candidates after a mass appeal across the island and an extensive and rigorous interview process.[34] Many of the prospective volunteers or "repatriates" who initially applied to the programme were found to be unsuitable: a few were lapsed Christians, one was excited about the adventure and wished to mine for gold, another had an invalid wife who was too ill to travel while other potential recruits wished merely to return to the motherland, Africa, the mission work not being a top priority in their minds. It was quite an arduous task finding the right candidates to the extent that Riis and other Basel missionaries almost gave up on the initiative.[10][11][34]

Riis met Clerk's teacher, the Moravian, Jacob Zorn who insisted on a proper contract of service between these Jamaican missionaries represented by the Conference of the Jamaican Moravian Mission and the Basel Mission. The agreement stipulated among other things,[10] that:

- "The form of public worship and the rules of the Moravian Church in regard to church discipline were to be maintained

- The West Indians were to undertake to serve the mission willingly. In return the mission would take care of all their needs for the first two years

- The Basel Mission would provide houses for the West Indians and give them land for farming and gardening, on which they could work one day per week

- At the end of the first two years, the West Indians could choose to either follow their own source of employment or to work for the Basel Mission at a reasonable wage

- After five years, if anyone wanted to return to Jamaica, the Basel Mission would pay the passage, provided that they had not been guilty of moral aberration."[10][13]

The provision which allowed the West Indian Moravians to use their own form of worship and discipline was an indication of the extent to which both the Moravians and the Basel Mission were prepared to go in order to enlist Afro-Caribbean Christians in the mission. Given the historical similarities between the Moravian and Basel missions due to their shared Lutheran heritage, the alliance was the commencement of a new and effective model in the mission entreprise which had profound socio-cultural effects on the indigenous community in Ghana.[10][19][28]

Before their departure from Jamaica, an emotional farewell service was held at the Moravian Churches at Lititz and Fairfield for the missionaries and their families.[10][13] Amidst tears and hugs, the West Indian emigrants made it known to their families and church congregations in a valedictory address telling them: “When we go to Africa, we go not to a foreign country. Africa is our country and our home. Our grandfathers and great-grandfathers were taken from there and brought here. We go there to witness the Grace of God not only to the European, but also to the African and our only prayer is that the eyes of the Africans whom we regard as our brothers may be opened to see Jesus Christ as Saviour of the World.”[10][11][34] The Jamaicans were essentially a bridge to share the Gospel with the Gold Coast natives while connecting with their ancestral and cultural roots in Africa.[13]

In an allegory of the Biblical Joseph narrative, a team of 24 Jamaicans and one Antiguan (6 distinct families and 3 bachelors) sailed from the port at Kingston on 8 February 1843 aboard the Irish brigantine, The Joseph Anderson, rented for £600, and according to varying historical accounts, arrived in Christiansborg, Gold Coast on Easter Sunday, 16 April or Easter Monday, 17 April 1843 at about 8 p.m. local time (GMT) after sixty-eight days and nights of voyage, enduring a five-day tropical storm on the Caribbean sea, shortage of fresh water and an oppressive heat aboard the vessel.[10][11][44][28] A short welcome ceremony was held for them by the Basel Mission at the Christiansborg Castle, where they were warmly received by Edvard James Arnold Carstensen, the Danish Governor at the time, together with George Lutterodt, a mulatto and personal friend of Andreas Riis who had earlier been acting Governor of the Gold Coast.[10][11] The West Indians rested for a while on the coast before leaving for Frederikgave on 10 May 1843, the old villa and royal plantation of the Danish Governor at modern day Sesemi village near the Akwapim hills.[13][28][45] While in Accra, half of the group stayed with Lutterodt while the rest of the West Indians stayed in the home of another Euro-African called Yestrop.[6]

Apart from A. W. Clerk from the Fairfield congregation, who was already a trained mission agent, other Moravian missionary recruits doubled as skilled craftsmen:[1][6][13]

- Joseph Miller of Fairfield, a farm worker, with his wife, Mary and children, Rose Ann, Robert and Catherine

- John Rochester of Fairfield, a cooper, with his wife Mary, sister, Ann and son John Powell Rochester

- James Greene of the Nazareth congregation, a carpenter, with his wife, Catherine and son, Robert

- John Hall of Irwin Hill, Montego Bay, a rum distiller and his wife Mary and son Andrew

- James G. Mullings of the Bethlehem church, a domestic servant, with his wife Margarethe and daughter, Catharine Elisa

- Edward Walker of the Bethlehem church, a farm worker, with wife, Sarah and son John

- David Robinson of Fulneck, a farm worker

- Jonas Horsford of the Grace Hill church, Liberta Village[46] in Antigua

In addition, the West Indians were accompanied by an Angolan-born, Jamaican-raised school teacher named Catherine Mulgrave, also from Fairfield who was the bride of George Peter Thompson and became the Headmistress of the then Danish-run Christiansborg Castle School in Osu, Accra, which was taken over by the Basel Mission.[47][48] Riis also had the Rev. Johann Georg Widmann, a German clergyman as his assistant. They also had donkeys, horses, mulls and other animals and agricultural seeds and cuttings such as mango seedlings which they were going to introduce to the Gold Coast economy.[10][47][49][48] Other tropical seedlings brought by the West Indian missionaries include cocoa, coffee, breadnut, breadfruit, guava, yam, cassava, plantains, cocoyam, variety of banana species and pear.[34] Cocoyam, for example, is now a Ghanaian staple.[34] Later on in 1858, the missionaries experimented with cocoa planting at Akropong, more than two decades before Tetteh Quarshie brought cocoa seedlings to the Gold Coast from the island of Fernando Po, now known as Bioko in the Equatorial Guinea.[34][50]

Mission enterprise at Akropong[]

Majority of the West Indians relocated to Akropong from Frederiksgave between 17 and 18 June 1843.[28] While at the villa, Mary Hall gave birth to her second son, Henry who was baptised by Johann Georg Widmann.[13] The local people received the West Indians with enthusiasm but were later disappointed "because we [the West Indians] did not bring them money and brandy" as remarked by one of the missionaries, Joseph Miller.[10] Nonetheless, they settled in and wholly "trusted the Akuapem people" and formed close friendships with the natives who became their interpreters as they could not originally communicate in the local Twi language; they later incorporated Akan vocabulary into their Jamaican Patois.[10] The political unrest in Akropong within the period 1839 to 1850 hampered the missionary effort.[10]

Clerk and his colleagues started work immediately since the houses they were promised were actually in disrepair.[10] As per historical literature, they built the first brick and stone houses in Akropong and the area of West Indian settlement became known as Hanover, a connection to the parish (region) in northwest Jamaica.[10] Hanover was described as a "community lined with mango trees" as seen in Jamaican neighbourhoods even today.[10] There is even a Hanover Street in Akropong built circa 1860: the street of little stone houses built by the Jamaicans which now runs parallel to the north boundary of the Presbyterian Training College (PTC).[10] There is still a water well called Jamaica in Aburi that was built by Jamaican Moravian, John Rochester and local labourers dating back to the 1850/60s.[1][10][51][40] Based on an 1851 headcount, 25 out of the total 31 Christians at Akropong were West Indian.[41] There was a cordial atmosphere in the West Indian community as the Caribbean settlers saw one another as brothers and sisters.[13]

Initially, as local mission president, Riis had to be master of all trades: pastor, administrator, bursar, accountant, carpenter, architect and a public relations officer between the Mission and the traditional rulers.[11][13] Hermann Halleur was the mission station manager responsible for all economic activities while J. G. Widmann was appointed the school inspector and Basel minister-in-charge of the Christ Presbyterian Church, Akropong.[13] As a result of his previous experience as an elder in his home church in Irwin Hill in Montego Bay, John Hall became the first Presbyter of the church while Alexander Worthy Clerk became the first deacon with an additional role in distributing food supplies like corn and imported clothing to his fellow Caribbean emigrants.[13] Clerk was also put in charge of teaching the children of the settlers at the then newly established infant school at Akropong.[13] John Rochester supervised the agricultural work of the mission.[13]

As more missionaries were recruited for the mission, the burden of the administrator increased. Riis and another Basel missionary, Simon Süss were forced by the situation to trade and barter in order to get money to buy food and other needs of his expanding mission staff and local workers.[11][51][40] The missionaries faced many difficulties and one of the many charges levelled against them by their detractors was that they had become commercial traders instead of church missionaries.[11] Riis and his men started evangelising to the rural people around Akropong; the Basel Mission became colloquially known as "rural" or "bush" church.[11] Riis wanted to address paganism inland and to learn the Akan language spoken more widely in the hinterlands of the Gold Coast. Riis as a disciplinarian suspended the Americo-Liberian missionary, George Thompson who failed in his mission at Osu in 1845.[11]

The first Christian baptisms were performed by the Jamaicans in 1847 when a theological seminary was established at Christiansborg, Osu.[13][41] Another seminary, the Basel Mission Seminary (later Presbyterian College of Education) was established in 1848 to train natives in the work of the mission.[41] Later on, the Christiansborg seminary was permanently moved to the Akropong campus and merged with the Basel Mission Seminary there. Upon the opening of the seminary, the Sierra Leonean Pan-Africanist, James Africanus Beale Horton noted that, "it is indeed an academic achievement which can very well hold its own in comparison with European Training Colleges of the period."[13] The school produced teacher-catechists whose roles were pivotal in Christian evangelism as the curriculum grounded students in the theory and practice of general education and pedagogy as well as a classic seminary training.[13] There were also plans in 1845 to import prospective students from Barbados but those plans were shelved as there was a greater need to train local scholars and preachers.[13] The catechist educational model was based on the Church Missionary Society system in which trained catechists who were non-ordained pastors and regarded as probationers for a number of years before being elevated to the position of church minister.[13]

Challenges in the early days were not uncommon.[1][51][40] It was documented that "by January 1845 some of the West Indian Christians had grown weary of the Christian experiment and wrote to the Basel Mission requesting repatriation to the West Indies but the mission refused” citing the signed agreement.[1][40][51] In 1848, a few West Indian emigrants opted to return to Jamaica upon the expiration of the five-year residency requirement in the original contract with the Basel Mission.[40] David Robinson died in 1850 on the Gold Coast from persistent illness.[1][40][51] As tensions continued to rise between the Basel Mission and the West Indians, the Walkers became disenchanted, left the mission station at Akropong and relocated to Accra before permanently settling in Cape Coast.[1][40][51] Some disagreements among the Caribbean settlers over the distribution of clothing supplies resulted in the flogging of Antiguan, Jonas Horsford by Andreas Riis and the labourer-foreman, Ashong.[13] Horsford, who was then in his early twenties, fled to Osu, Accra and later, Cape Coast out of anger and humiliation.[13] He was voluntarily repatriated to Antigua but died at sea on his way home.[13] The Greenes requested repatriation to Jamaica in 1849, only for Catherine, wife of James to die at sea from apparent terminal breast cancer which was diagnosed while she was living in Akropong.[13] A Basel missionary, Johann Friedrich Meischel believed Mrs. Catherine Greene negatively influenced her husband to be wary of the European missionaries as the Greenes thought the society would renege on its promise to repatriate Caribbean missionary-volunteers after five years if they desired to.[13]

Five Caribbean families remained to form the nucleus of the African Christian community at Akropong: Alexander Worthy Clerk, John Hall, Joseph Miller, James Gabriel Mullings, John Powell Rochester and their respective families.[1][40][51][52] According to historical archives,"…the mission took steps to secure farming land for the West Indian families that decided to stay. The mission purchased land near Adami for the Miller and the Hall families and at Adobesum on the road to Amanprobi for the Mullings and Rochester families. Land was secured for the Clerk family in Aburi at a place called Little Jamaica today.”[1][40][51]

He was a missionary in villages and towns in the Akuapem area from 1864 and 1867. In 1867, Clerk was sent to Tutu, a town in the Akuapem area and raised funds locally for the construction of the first Basel Mission chapel there.[13] On 1 September 1872, together with indigenous Akan native pastor, Theophilus Opoku, Alexander Worthy Clerk was ordained a full Basel Mission minister by the Basel missionary, the Rev. Johann Georg Widmann.[13][53] The Gold Coast historian, Carl Christian Reindorf was ordained six weeks later on 13 October 1872.[13][54][55] This ceremony was the beginning of ordination of local pastors for mission work.[13] He later became the district minister of the Basel Mission Church at Aburi.[13]

Contributions to education[]

Clerk and his fellow Caribbean missionaries were self-motivated and adapted quickly despite the initial homesickness and learnt the indigenous languages of Akan and Ga.[10][56][57] The missionaries composed new local language hymns, translated church hymns into Ga and Akan from English and German, built stone houses, water wells and schools, set up large farms and taught the local people to read and write vastly improving literacy in the region.[10][47][49][48] In 1848, thirty-seven girls, twenty-five boys and seven children of the West Indians attended the newly set-up, United Akropong School with Clerk as a founding schoolmaster.[1][13][40][51] As a result of his hardwork, Clerk was nicknamed, "Suku Mansere", a bastardisation of "schoolmaster" in the Twi language.[13] The West Indian children who were taught at the school included Andrew Hall, Rose Ann Miller, Robert Miller, Catherine Miller, Elizabeth Mullings, Ann Rochester and John Rochester. The girls’ school was later transferred to Aburi in 1854 to become the Girls’ Senior School, predecessor to the present-day Aburi Girls’ Secondary School.[1][40][51] Rose-Ann Miller, daughter of Jamaican missionaries, Joseph and Mary Miller, who had previously run the infant school at Akropong in 1857 was put in charge of the girls' school at Aburi in 1859 until 1874 when she voluntarily left the Basel Mission to work at the state-run Government Girls' School in Accra.[13]

Clerk and other missionaries also trained native catechists to help them in their evangelical work and play significant roles in the Basel Mission[10][47][48] at the then newly established Basel Mission Training College in 1848 (now Presbyterian College of Education)[10] as the second oldest higher educational institution in West Africa after Fourah Bay College (founded in 1827)[58] in Freetown, Sierra Leone.[59] At the seminary, Clerk was given a new role as an instructor of Biblical studies.[13] Clerk's students in the pioneer class included John Powell Rochester, David Asante, Paul Staudt Keteku, William Yirenkyi and Jonathan Bekoe Palmer.[13] These seminarians later became teacher-catechists and pastors in the service of the mission.[13]

A few years earlier, on 27 November 1843, an English language all boys’ boarding middle school, the Salem School was opened at Christiansborg, the oldest existing school founded by the Basel Mission. The founding educators were all missionaries: Jamaicans, Alexander Worthy Clerk and Catherine Mulgrave (1827–1891) as well as George Thompson, the German-trained Americo-Liberian missionary.[15] Mulgrave was born in Angola but raised in Jamaica after being rescued as a six-year old from Portuguese slave traders.[15] She recalled her mother calling her by the Angolan name "Gewe" as a child and was adopted by the then Governor of Jamaica, Earl of Mulgrave and his wife, Lady Mulgrave who educated her at the Female Refuge School followed by teacher training at the Mico Institution in Kingston, Jamaica.[1] Between 1843 and 1891, Mulgrave also established various boarding schools for girls at Osu, Abokobi and Odumase, with curricula that emphasised arithmetic, reading, writing, needlework, gardening and household chores.[13]

The West Indians introduced English as the preferred medium of instruction in school and this gained wide acceptance after the Danes sold their forts and castles on the eastern board of the Gold Coast, including Osu, to the British in 1850.[15] In the 19th century, the name Salem described that part of town where the early European Basel missionaries had settled together with their converts. Originally, the term Salem included the church, the school and other buildings in the Christian quarter of the town[15] The school was built around a quadrangle with the classrooms on one side, dormitories on the other and the headmaster's and teachers’ residences on the other side. This arrangement kept teachers and pupils in constant touch with one another.[15] Salem, therefore had a "Christian village culture" that was typical in the European small towns and villages many Basel missionaries hailed from.[13]

The school curriculum was rigorous: It included English and Ga languages, arithmetic, geography, history, religious knowledge, nature study, hygiene, handwriting and music.[15] There was also instruction in arts and crafts, including pottery, carpentry, basket and mat weaving and practical lessons in agriculture on the school farm.[15] Christian religious training was core to the curriculum with compulsory church attendance required of all pupils.[15] A strict disciplinary code, based on austere living was enforced.[15]

The early years of the school were difficult. Within a year of its establishment, Clerk was sent to Akropong to start a similar school there.[15] In 1854, the British authorities, aided by the colonial forces, bombarded the town of Osu for two days using the warship, "H.M. Scourge" after the indigenes refused to pay the newly imposed poll-tax.[15] Several parts of the town were destroyed. The young school together with a large number of new African converts moved to Abokobi. The school was transferred back to Osu to the place called Salem around 1857.[15] Later, similar Salem schools were established in Peki, La, Teshie, Odumase, Ada Foah, Kibi, Abetifi and Nsaba.[15]

Many of the school's alumni later became administrators, accountants, bankers, civil servants, dentists, diplomats, engineers, judges, lawyers, medical doctors, political leaders, professors and teachers in the colonial era.[15] The Christian-rooted Basel training the Salem alumni received in their formative years instilled in them a strong sense of noblesse oblige.[15] From the mid nineteenth century to the latter part of the twentieth century, Salem old boys dominated many facets of public life and society, and formed a nucleus of the nouvelle haute bourgeoisie in the Gold Coast colonial social hierarchy.[15]

Despite being highly educated by all standards; self-taught and multilingual in several Ghanaian, Caribbean and European languages (Ga, Twi, English, Jamaican Creole and German), the Home Committee in Basel never accorded Clerk the full or maximum respect he deserved as a Basel missionary, minister and educator during his lifetime.[10] He and his other Caribbean colleagues in particular, were instead seen by the Europeans as having the same status as administrative assistants or mission helps, leading sometimes to strained relations with the Basel Mission.[10]

Personal life and ancestry[]

Lineage[]

Clerk was a descendant of eighteenth century West African slaves who were captured by slave traders and forcibly brought to the Caribbean island to work on coffee and sugar plantations at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.[10][23][24][60] Some of these Jamaican slaves were possibly of Asante origin as per some oral narratives, and from the middle belt of present-day Ghana, while others originated from the Ghanaian coastal corridor, largely populated by Gas and Fantes. Later on, many slaves were also taken from Igbo and Yoruba communities in modern-day Sierra Leone and Nigeria.[60]

Marriage[]

On 30 August 1848, Clerk married Pauline Hesse (born 3 May 1831) of Osu Amantra, the daughter of a Euro-Ga merchant, Herman Hesse of the Hesse family and a Ga-Dangme woman, Charlotte Lamiorkai, who hailed from a trading family at Shai Hills.[1][2][3][9][61][62] Pauline Hesse's paternal grandfather, Dr. Lebrecht Wilhelm Hesse, was an eighteenth century-Danish physician of German ethnicity.[1] Hesse-Clerk was Basel Mission-trained and educated at the Danish language Christiansborg Castle School in Osu.[1][63] One of her schoolteachers was Catherine Mulgrave, the Basel Mission's first woman educator on the Gold Coast.[1] Hesse's schoolmates included her sisters, Mary (Mrs. Richter), Wilhelmina (Mrs. Briandt), Regina (1832 –1898), a teacher who later married Hermann Ludwig Rottmann, the first Basel missionary-trader in Christiansborg and the founder of the Basel Mission Trading Company.[1][6][13][62] Her brother, William Hesse (1834 –1920) was Basel Mission pastor. Another schoolmate was the historian and minister, Carl Christian Reindorf (1834 –1917), whose seminal book, The History of the Gold Coast and Asante, was published in 1895.[63][64][65][66] The Christiansborg Castle School, opened in 1722, was very similar to the Cape Coast Castle School established by the Anglican vicar, the Reverend Thompson and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) affiliated to the Church of England[67][68] Danish was the medium of instruction at the Christiansborg School.[15] The castle schools were established by the European Governors to baptise and primarily educate the male Euro-African mulatto children of European men and Gold Coast African women for eventual employment as administrative assistants and soldiers in the colonial civil service.[67][31][68] Later on, Hesse-Clerk became a small business owner and a commercial trader.[1] As a result of the 1854 bombardment of Osu and the ensuing forced displacement of its residents, a brother-in-law of Clerk, John Hesse, relocated to Akropong as a domestic refugee and engaged in petty trading together with other Ga-Dangme traders who had also fled the bombing.[15][28] Due to her upbringing, education and trade, Pauline Hesse was multilingual, speaking Ga, Akuapem Twi, English, Danish and German.

The couple had twelve children but one, the Rev. A. W. Clerk's namesake, Alexander Worthy, died at birth: Caroline Rebecca (Mrs. Svaniker), John Patrick, Louisa (Mrs. Hall), Ophelia (died in childhood from measles), Charles Emmanuel, Richard Alfred, Nicholas Timothy, Jane Elizabeth (Mrs. Bruce), Mary Anne, Matilda Johanna (Mrs. Lokko) and Christian Clerk who died in his youth in a drowning accident in the Gulf of Guinea.[1][6][69][28] Thus, A. W. Clerk became the patriarch of the historically notable Clerk family of Accra by virtue of his 1843 arrival to the Gold Coast as a bachelor and his subsequent 1848 marriage to Pauline Hesse.[18]

Selected works[]

A. W. Clerk wrote and translated hymns from German into the Ga language. These hymns are captured in the Presbyterian Hymnals and are still used by the Presbyterian Church of Ghana for its church services:

- Mɛni Yesu efee eham'? - What is there Christ has done for me? (PHB 497)[56][57]

- Mɔ ni ji Kristo kaselɔ - All you that follow Jesus Christ (PHB 528), translated from a German hymn, originally written by the Swiss-Italian Pietist theologian and hymn composer, Hieronymus Annoni (1697 – 1770)[56][57][70]

Death and legacy[]

Clerk died of natural causes on 11 February 1906, three weeks before his eighty-sixth birthday[4][18][5] at his home, Fairfield House, in Aburi,[71] 20 miles (32 km) north of Accra. He was buried at the old Basel Mission Cemetery near the Aburi Botanical Gardens in Aburi.[5] As an opinion leader at Aburi, Clerk had been influential in the choice of the campus of the botanical garden. Clerk's widow, Pauline Hesse-Clerk died on 18 August 1909 at the age of 78 years; she was buried next to her husband.

During World War I, German missionaries working left the Gold Coast and Scottish Presbyterian missionaries came and served the Christians of the Moravian Church.[10] Sometime after the war ended, the Germans sought to renew their dominant influence but the Gold Coast Christians declared a strong preference for the Presbyterian Church brought there by the Scots.

In a fitting tribute to the legacy of Clerk, other West Indian missionaries and the Basel Mission, the British Governor of the Gold Coast during World War I, Sir Frederick Gordon Guggisberg, reacted to the expulsion of Basel Mission as alien security risk from the Gold Coast by lamenting that, the forced departure was "the greatest blow which education in this country has ever suffered;" describing their work as the "first and foremost as regards quality of education and character training" – a testament to the mission's approach of combining academic study with practical training for life.[17] While propagation of the Gospel was the main objective of the West Indians and the Basel Mission, the domestic socioeconomic and dire educational environment motivated them to establish the first formal schools and colleges in the country, open to pupils from all walks of life.[35] Moreover, the missionaries provided alternative sources of employment to rural inhabitants through the establishment of mechanized agriculture and commerce-driven small-scale artisanal industries such as construction and craftsmanship including printing, book-binding, tile manufacturing, brick-making and weaving in order to create self-sufficiency among the natives.[35][42] To accentuate this point, the scholar, Noel Smith noted in 1966, "In education and in agriculture, in artisan training and in the development of commerce, in medical services and in concern for the social welfare of the people, the name 'Basel' by the time of the expulsion of the Mission from the country had become a treasured word in the minds of the people."[13]

The Presbyterian Church of Ghana today duly remembers and recognises Clerk and the other West Indian missionaries for their pioneering role in the Protestant Christian movement in Ghana.[10] The church continues to maintain much of the Jamaican church liturgy, order and discipline that were imported to Ghana in the nineteenth century and is a strong mission-minded one.[10][23] The denomination currently has nearly 1 million members constituting about a quarter of the Ghanaian Christian Protestant demographic and about four-percent of the national population.[72] The Presbyterian Church of Ghana today has instituted "Presbyterian Day" or "Ebenezer Day", a special Sunday designated in the church almanac to honour the memories, selfless work and toil of the missionaries in the early years.[72] The names of Alexander Clerk and his son Nicholas Clerk appear on a commemorative plaque in the sanctuary of the Ebenezer Presbyterian Church, Osu, listing pioneering missionaries of the church, in recognition of their contributions to formal education and the growth of the Presbyterian faith in Ghana.[73] In the sanctuary of the Christ Presbyterian Church, Akropong, a tablet memorialises the life and work of Alexander W. Clerk and his Caribbean compatriots, Joseph Miller, John Hall, John Rochester, James Mullings, John Walker, James Green and Antiguan Jonas Horsford.

In addition to increased access to education, A. W. Clerk and other Basel Mission and West Indian missionaries were also instrumental in the expansion of hospitals, social welfare programs, medical services or healthcare as well as the development of infrastructure including roads and the growth of commerce and agriculture to support church mission activities.[38] Today, the church maintains schools, colleges and health centres in many cities and towns in Ghana including Abetifi, Aburi, Agogo, Bawku, Donkorkrom, Dormaa Ahenkro and Enchi.[38] In order to preserve the old culture, the usage of vernacular as the principal medium of ministry continues to be emphasised by the Presbyterian Church of Ghana.[38]

Clerk's lineage or progeny has played pioneering roles in the development of architecture, church development, civil service, diplomacy, education, health services, journalism, medicine, natural sciences, public administration, public health public policy and urban planning on the Gold Coast and in modern Ghana.[48] His son, Nicholas Timothy Clerk was a Basel-trained theologian who served as the first Synod Clerk of the Presbyterian Church of the Gold Coast from 1918 to 1932 campaigned for a secondary school, culminating in the establishment of Presbyterian Boys' Secondary School in 1938.[7][15][17] Peter Hall, the son of John Hall, Clerk's fellow Jamaican missionary, was also elected the first Moderator of Presbyterian Church of the Gold Coast in 1918.[47][28] Other second generation descendants of the Jamaicans who were instrumental in strengthening the country's educational foundations laid by their Caribbean forebears include John Powell Rochester, Timothy Mullings, Henry Hall, James Hall, Caroline Clerk, Patrick Clerk, Charles Clerk, Rose Ann Miller and Emil Miller.[1][13] As agriculturists, educators, craftsmen and preachers, they toiled to provide formal education in the communities they worked in.[13]

Bibliography[]

Notes[]

- Genealogical research based on a registry of Jamaican births and baptisms between 1752 and 1920 showed earlier records of a Jamaican family with the Clerk surname, though unrelated to Alexander Worthy Clerk.[74][75][76][77][78][79][80]

- An individual named John Clerk (the older) had his two children, James Shaw Clerk and Mary Ann Clerk baptised on 21 November 1793 at St. James, Trelawny in the county of Cornwall, Jamaica.[74]

- Other members of this family were Fanny, Richard Brian and John Clerk (the younger), all christened on 30 August 1798 in Hanover, Jamaica.[74]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Sill, Ulrike (2010). Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood: The Basel Mission in Pre- and Early Colonial Ghana. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004188884.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Jena, Geographische Gesellschaft (für Thüringen) zu (1891). Mitteilungen (in German). G. Fischer. p. 77.

nicholas timothy clerk basel.

- ^ a b Jena, Geographische gesellschaft (für Thüringen) zu (1890). Mitteilungen der Geographischen gesellschaft (für Thüringen) zu Jena (in German). G. Fischer. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b c History in Africa. African Studies Association. 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Debrunner, Hans W. (1965). Owura Nico, the Rev. Nicholas Timothy Clerk, 1862–1961: pioneer and church leader. Watervile Publishing House.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Clerk, Nicholas, Timothy (1943). The Settlement of West Indian Emigrants in the Gold Coast 1843–1943 – A Centenary Sketch. Accra.

- ^ a b c "Clerk, Nicholas Timothy, Ghana, Basel Mission". www.dacb.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Allgemeine Missions-Zeitschrift (in German). M. Warneck. 1903. p. 80.

alexander worthy clerk.

- ^ a b Kingdon, Zachary (21 February 2019). Ethnographic Collecting and African Agency in Early Colonial West Africa: A Study of Trans-Imperial Cultural Flows. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 214, 219. ISBN 9781501337949.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Dawes, Mark (2003). "A Ghanaian church built by Jamaicans". Jamaican Gleaner. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "NUPS-G KNUST>>PCG>>History". www.nupsgknust.itgo.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Sundkler, Bengt; Steed, Christopher (4 May 2000). A History of the Church in Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 719. ISBN 9780521583428. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av Kwakye, Abraham Nana Opare (2018). "Returning African Christians in Mission to the Gold Coast". Studies in World Christianity. 24 (1): 25–45. doi:10.3366/swc.2018.0203.

- ^ Gilroy, Paul (1993). The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Verso. ISBN 9780860916758. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Osu Salem". osusalem.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Presbyterian College of Education, Akropong". Presby. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "PRESEC | ALUMINI PORTAL". www.odadee.net (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "International Mission Photography Archive, ca.1860-ca.1960". Retrieved 29 March 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood | Brill. www.brill.com. Brill. 7 July 2010. ISBN 9789004193734. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Periodical Accounts Relating to the Missions of the Church of the United Brethren Established Among the Heathen, Volume 16. Brethren's Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel. 1841.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Herppich, Birgit (31 October 2016). Pitfalls of Trained Incapacity: The Unintended Effects of Integral Missionary Training in the Basel Mission on its Early Work in Ghana (1828-1840). James Clarke Company, Limited. pp. 326, 328. ISBN 9780227905883. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018.

- ^ Vig, Peter Sorensen (1907). Danske i Amerika (in Danish). C. Rasmussen publishing Company.

- ^ a b c d Antwi, Daniel J. (1998). "The African Factor in Christian Mission to Africa: A Study of Moravian and Basel Mission Activities in Ghana". International Review of Mission B. 87 (344): 55–56. doi:10.1111/j.1758-6631.1998.tb00066.x.

- ^ a b Newman, Las (2007). Historical Missionology: A critical analysis of West Indian participation in the Western missionary enterprise in Africa in the 19th century. Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, England.

- ^ a b Periodical Accounts Relating to the Missions of the Church of the United Brethren Established Among the Heathen, Volume 15. Brethren's Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel. 1839.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Periodical Accounts Relating to the Missions of the Church of the United Brethren Established Among the Heathen, Volume 21. Brethen's Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel. 1853.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Moravian Archives". www.moravianchurcharchives.findbuch.net. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hall, Peter (1965). Autobiography of Peter Hall. Accra: Waterville Publishing House.

- ^ "Fairfield Moravian, Manchester". Jamaican Ancestral Records. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "History – Moravian Church in Jamaica and the Cayman Islands". jamaicamoravian.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d "History of Education in Ghana – Great Pola Africa Foundation". politicalpola.wikifoundry.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Grant, Paul (2014). "Dying German in Ghana: The Basel Mission Wrestles with Grief, 1830–1918". Studies in World Christianity. 20 (1): 4–18. doi:10.3366/swc.2014.0068. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018.

- ^ "Lost in Transition: Missionary Children of the Basel Mission in the Nineteenth Century". www.internationalbulletin.org. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Akyem Abuakwa Presbytery Youth: PCG History". Akyem Abuakwa Presbytery Youth. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d "South India remembers sacrifice of Basel missionaries | Christian News on Christian Today". www.christiantoday.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b Joeden-Forgey, Elisa von (November 2004). "Review of Miller, Jon, Missionary Zeal and Institutional Control: Organizational Contradictions in the Basel Mission on the Gold Coast, 1828-1917". www.h-net.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Agbeti, J. Kofi (1986). West African Church History. Brill Archive. p. 62. ISBN 978-9964912703.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d PCG. "Brief History Of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana". pcgonline.io. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ svendHistorie (30 May 2018). "Ghana – The Gold Coast". Historie. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Coe, Cati (1 November 2005). Dilemmas of Culture in African Schools: Youth, Nationalism, and the Transformation of Knowledge. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226111315.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Yeboah Laryea, Daniel (30 June 2015). "The Beginnings of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana". yldaniel. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Role of Basel missionaries still relevant - Okuapehene". www.ghanaweb.com. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Seth, Quartey. "Andreas Riis: a lifetime of colonial drama". Research Review of the Institute of African Studies. 21. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017.

- ^ a b Owusu-Agyakwa, Gladys; Ackah, Samuel K.; Kwamena-Poh, M. A. (1994). The mother of our schools: a history of the Presbyterian Training College, Akropong-Akuapem and biography of the principals, 1848-1993. Presbyterian Training College. p. 8. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Frederiksgave Plantation and Common Heritage Site" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Gracehill Antigua Church: Moravian Church Celebrates 240 Years". www.antiguanice.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Anquandah, James (2006). Ghana-Caribbean Relations – From Slavery Times to Present: Lecture to the Ghana-Caribbean Association. National Commission on Culture, Ghana.

- ^ a b c d e

Anquandah, James (2006). Ghana-Caribbean Relations – From Slavery Times to Present: Lecture to the Ghana-Caribbean Association. National Commission on Culture, Ghana:"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Anfinsen, Eirik. "Bischoff.no – Bischoff.no is the personal blog of Eirik Anfinsen – co-founder of Cymra, anthropologist, and general tech-enthusiast". Bischoff.no. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Missionary Spotlight – Ghana's Christian legacy | Evangelical Times". www.evangelical-times.org. April 2006. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sackey, Brigid M. (2006). New Directions in Gender and Religion: The Changing Status of Women in African Independent Churches. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739110584.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Boadi-Siaw, S. Y. (2013). "Black Diaspora Expatriates in Ghana Before Independence". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana (15): 128. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 43855014.

- ^ Ofosu-Appiah, L. H. "Opoku, Theophilus 1824-1913 Basel Mission Ghana". dacb.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ ""Obstinate" Pastor and Pioneer Historian: The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf". www.internationalbulletin.org. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Ofosu-Appiah, L. H. "Carl Christian Reindorf". Dictionary of African Christian Biography (online ed.). Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Presbyterian Hymn Book - Ga Hymnal. Accra: Waterville Publishing House. 2000. pp. 234–235, 250.

- ^ a b c Presbyterian Hymn Book - English Hymnal. Accra: Waterville Publishing House. 2014. pp. 282, 300.

- ^ "PRESEC | ALUMINI PORTAL". www.odadee.net (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ "About PUCG | Presbyterian University College, Ghana". www.presbyuniversity.edu.gh. 7 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ a b "On the Plantations: The Abolition of Slavery Project". abolition.e2bn.org. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Family Tree - Doku Web Site - MyHeritage". www.myheritage.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b Veit, Arlt (2005). Christianity, imperialism and culture : the expansion of the two Krobo states in Ghana, c. 1830 to 1930. edoc.unibas.ch (Thesis). doi:10.5451/unibas-003662454. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ a b Agyemang, Fred M. (2006). Our Presbyterian heritage. Pedigree Publications. pp. 37, 124. ISBN 9789988029210.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Reindorf, Carl Christian, Ghana, Presbyterian". www.dacb.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Carl Christian Reindorf, Ghana, Basel Mission". www.dacb.org. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ ""Obstinate" Pastor and Pioneer Historian: The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf". www.internationalbulletin.org. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ a b Graham, C. K. (1971). The History of Education in Ghana from the Earliest Times to the Declaration of Independence. F. Cass. ISBN 9780714624570.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Jenkins, Paul (1998). The Recovery of the West African Past: African Pastors and African History in the Nineteenth Century : C.C. Reindorf & Samuel Johnson : Papers from an International Seminar Held in Basel, Switzerland, 25-28th October 1995 to Celebrate the Centenary of the Publication of C.C. Reindorf's History of the Gold Coast and Asante. Basler Afrika Bibliographien. ISBN 9783905141702.

- ^ "FamilySearch.org". familysearch.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Hieronymus Annoni - Hymnary.org". hymnary.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ Al, Fashion Et (12 May 2013). "Ghana Rising: History: Ghana's Majestic Past –People & Culture in Black & White from 1850 - 1950". Ghana Rising. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Presbyterian Church of Ghana". www.pcg.pcgonline.io. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Innovation, Osis. "Osu Eben-ezer Presbyterian Church". osueben-ezer.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "FamilySearch.org". familysearch.org. Retrieved 9 May 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Watson, Karl (2008). "Review of The Last Colonials: The Story of Two European Families in Jamaica". NWIG: New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 82 (1/2): 162–165. ISSN 1382-2373. JSTOR 43390725.

- ^ Jensen, Peta Gay (2005). The Last Colonials: The Story of Two European Families in Jamaica. Radcliffe. ISBN 978-0-7556-2457-7.

- ^ Jensen, Peta Gay (29 July 2005). The Last Colonials: The Story of Two European Families in Jamaica. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84511-033-8.

- ^ Jensen, Peta Gay. "The Last Colonials". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Jensen, Peta Gay. "The Last Colonials". Half Price Books. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Last Colonials: The Story of Two European Families in Jamaica - AbeBooks - Jensen, Peta Gay: 1845110331". www.abebooks.com. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- 1820 births

- 1906 deaths

- Christian missionaries in Africa

- Clerk family of Ghana

- Gold Coast (British colony) people

- Jamaican emigrants to Ghana

- Jamaican Protestants

- Jamaican Protestant missionaries

- Jamaican people of the Moravian Church

- Jamaican educators

- Moravian Church missionaries

- Protestant missionaries in Ghana

- Presbyterian College of Education, Akropong faculty

- Osu Salem School teaching staff

- Afro-Jamaican