Gospel

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

Gospel originally meant the Christian message,[note 1] but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out;[2] in this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words and deeds of Jesus of Nazareth, culminating in his trial and death and concluding with various reports of his post-resurrection appearances.[3]

The four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John share the same basic outline: Jesus begins his public ministry in conjunction with that of John the Baptist, calls disciples, teaches and heals and confronts the Pharisees, dies on the cross, and is raised from the dead.[4] Each has its own distinctive understanding of Jesus and his divine role:[5] Mark never calls him "God",[6] Luke expands on Mark while eliminating some passages entirely, but still follows his plot more faithfully than does Matthew,[7] and John, the most overtly theological, is the first to make Christological judgements outside the context of the narrative of Jesus's life.[5] They contain details which are irreconcilable, and attempts to harmonize them would be disruptive to their distinct theological messages.[8] They were probably written between AD 66 and 110.[9][10][11] All four were anonymous (the modern names were added in the 2nd century), almost certainly none were by eyewitnesses, and all are the end-products of long oral and written transmission.[12] Mark was the first to be written, using a variety of sources;[13][14] the authors of Matthew and Luke, acting independently, used Mark for their narrative of Jesus's career, supplementing it with the collection of sayings called the Q document and additional material unique to each;[15] and there is a near-consensus that John had its origins as a "signs" source (or gospel) that circulated within a Johannine community.[16] The contradictions and discrepancies between the first three and John make it impossible to accept both traditions as equally reliable.[17] Modern scholars are cautious of relying on the gospels uncritically, but nevertheless they do provide a good idea of the public career of Jesus, and critical study can attempt to distinguish the original ideas of Jesus from those of the later authors.[18][19]

Many non-canonical gospels were also written, all later than the four canonical gospels, and like them advocating the particular theological views of their various authors.[20][5] Important examples include the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, the Gospel of Judas, the Gospel of Mary, infancy gospels such as the Gospel of James (the first to introduce the perpetual virginity of Mary), and gospel harmonies such as the Diatessaron.

Canonical gospels[]

Contents[]

The four canonical gospels share the same basic outline of the life of Jesus: he begins his public ministry in conjunction with that of John the Baptist, calls disciples, teaches and heals and confronts the Pharisees, dies on the cross, and is raised from the dead.[4] Each has its own distinctive understanding of him and his divine role:[5] Mark never calls him "God" or claims that he existed prior to his earthly life, apparently believes that he had a normal human parentage and birth, makes no attempt to trace his ancestry back to King David or Adam, and originally had no post-resurrection appearances,[6] [21] although Mark 16:7, in which the young man discovered in the tomb instructs the women to tell "the disciples and Peter" that Jesus will see them again in Galilee, hints that the author knew of the tradition.[22] Matthew and Luke base their narratives of the life of Jesus on that in Mark, but each makes subtle changes, Matthew stressing Jesus's divine nature – for example, the "young man" who appears at Jesus' tomb in Mark becomes a radiant angel in Matthew.[23][24] Similarly, the miracle stories in Mark confirm Jesus' status as an emissary of God (which was Mark's understanding of the Messiah), but in Matthew they demonstrate divinity.[25] Luke, while following Mark's plot more faithfully than does Matthew, has expanded on the source, corrected Mark's grammar and syntax, and eliminated some passages entirely, notably most of chapters 6 and 7.[7] John, the most overtly theological, is the first to make Christological judgements outside the context of the narrative of Jesus's life.[5] Scholars recognise that the differences of detail between the gospels are irreconcilable, and any attempt to harmonise them would only disrupt their distinct theological messages.[8]

Matthew, Mark and Luke are termed the synoptic gospels because they present very similar accounts of the life of Jesus. John presents a significantly different picture of Jesus's career,[26] omitting any mention of his ancestry, birth and childhood, his baptism, temptation and transfiguration.[26] John's chronology and arrangement of incidents is also distinctly different, clearly describing the passage of three years in Jesus's ministry in contrast to the single year of the synoptics, placing the cleansing of the Temple at the beginning rather than at the end, and the Last Supper on the day before Passover instead of being a Passover meal.[27] The Gospel of John is the only gospel to call Jesus God. In contrast to Mark, where Jesus hides his identity as messiah, in John he openly proclaims it.[28]

Composition[]

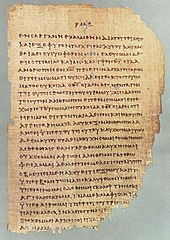

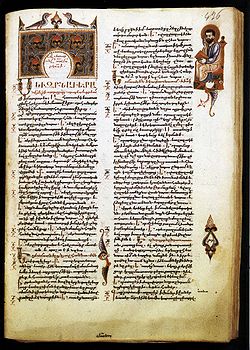

Like the rest of the New Testament, the four gospels were written in Greek.[30] The Gospel of Mark probably dates from c. AD 66–70,[9] Matthew and Luke around AD 85–90,[10] and John AD 90–110.[11] Despite the traditional ascriptions, all four are anonymous and most scholars agree that none were written by eyewitnesses.[12] A few conservative scholars defend the traditional ascriptions or attributions, but for a variety of reasons the majority of scholars have abandoned this view or hold it only tenuously.[31]

In the immediate aftermath of Jesus' death his followers expected him to return at any moment, certainly within their own lifetimes, and in consequence there was little motivation to write anything down for future generations, but as eyewitnesses began to die, and as the missionary needs of the church grew, there was an increasing demand and need for written versions of the founder's life and teachings.[32] The stages of this process can be summarised as follows:[33]

- Oral traditions – stories and sayings passed on largely as separate self-contained units, not in any order;

- Written collections of miracle stories, parables, sayings, etc., with oral tradition continuing alongside these;

- Written proto-gospels preceding and serving as sources for the gospels – the dedicatory preface of Luke, for example, testifies to the existence of previous accounts of the life of Jesus.[34]

- Gospels formed by combining proto-gospels, written collections and still-current oral tradition.

Mark is generally agreed to be the first gospel;[13] it uses a variety of sources, including conflict stories (Mark 2:1–3:6), apocalyptic discourse (4:1–35), and collections of sayings, although not the sayings gospel known as the Gospel of Thomas and probably not the Q source used by Matthew and Luke.[14] The authors of Matthew and Luke, acting independently, used Mark for their narrative of Jesus's career, supplementing it with the collection of sayings called the Q document and additional material unique to each called the M source (Matthew) and the L source (Luke).[15][note 2] Mark, Matthew and Luke are called the synoptic gospels because of the close similarities between them in terms of content, arrangement, and language.[35] The authors and editors of John may have known the synoptics, but did not use them in the way that Matthew and Luke used Mark.[36] There is a near-consensus that this gospel had its origins as a "signs" source (or gospel) that circulated within the Johannine community (the community that produced John and the three epistles associated with the name), later expanded with a Passion narrative and a series of discourses.[16][note 3]

All four also use the Jewish scriptures, by quoting or referencing passages, or by interpreting texts, or by alluding to or echoing biblical themes.[38] Such use can be extensive: Mark's description of the Parousia (second coming) is made up almost entirely of quotations from scripture.[39] Matthew is full of quotations and allusions,[40] and although John uses scripture in a far less explicit manner, its influence is still pervasive.[41] Their source was the Greek version of the scriptures, called the Septuagint – they do not seem familiar with the original Hebrew.[42]

Genre and historical reliability[]

The consensus among modern scholars is that the gospels are a subset of the ancient genre of bios, or ancient biography.[43] Ancient biographies were concerned with providing examples for readers to emulate while preserving and promoting the subject's reputation and memory; the gospels were never simply biographical, they were propaganda and kerygma (preaching).[44] As such, they present the Christian message of the second half of the first century AD,[45] and as Luke's attempt to link the birth of Jesus to the census of Quirinius demonstrates, there is no guarantee that the gospels are historically accurate.[46]

The majority view among critical scholars is that the authors of Matthew and Luke have based their narratives on Mark's gospel, editing him to suit their own ends, and the contradictions and discrepancies between these three and John make it impossible to accept both traditions as equally reliable.[17] In addition, the gospels we read today have been edited and corrupted over time, leading Origen to complain in the 3rd century that "the differences among manuscripts have become great, ... [because copyists] either neglect to check over what they have transcribed, or, in the process of checking, they make additions or deletions as they please".[47] Most of these are insignificant, but many are significant,[48] an example being Matthew 1:18, altered to imply the pre-existence of Jesus.[49] For these reasons modern scholars are cautious of relying on the gospels uncritically, but nevertheless they do provide a good idea of the public career of Jesus, and critical study can attempt to distinguish the original ideas of Jesus from those of the later authors.[18][19]

Scholars usually agree that John is not without historical value: certain of its sayings are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, its representation of the topography around Jerusalem is often superior to that of the synoptics, its testimony that Jesus was executed before, rather than on, Passover, might well be more accurate, and its presentation of Jesus in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically plausible than their synoptic parallels.[50] Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that the author had direct knowledge of events, or that his mentions of the Beloved Disciple as his source should be taken as a guarantee of his reliability.[51]