Second Epistle of John

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

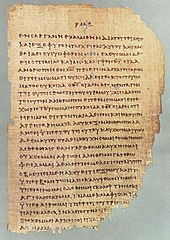

| New Testament manuscripts |

The Second Epistle of John, often referred to as Second John and often written 2 John or II John, is a book of the New Testament attributed to John the Evangelist, traditionally thought to be the author of the other two epistles of John, and the Gospel of John (though this is disputed). Most modern scholars believe this is not John the Apostle, but in general there is no consensus as to the identity of this person or group. (See Authorship of the Johannine works.)

Second John and Third John are the two shortest books in the Bible. The shortest book in the English language is different depending on which translation (version) you look at. For example, in the New International Version 2 John is the shortest book with only 302 words but in the King James Version (Authorized Version) 3 John is the shortest with only 295 words. However, Second John has the fewest verses in the Bible with only 1 chapter made up of only 13 verses.

Composition[]

The language of this epistle is remarkably similar to 3 John. It is therefore suggested by a few that a single author composed both of these letters. The traditional view contends that all the letters are by the hand of John the Apostle, and the linguistic structure, special vocabulary, and polemical issues all lend toward this theory.[1]

Also significant is the clear warning against paying heed to those who say that Jesus was not a flesh-and-blood figure: "For many deceivers are entered into the world, who confess not that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh." This establishes that, from the time the epistle was first written, there were those who had docetic Christologies, believing that the human person of Jesus was actually pure spirit or not come at all.[2]

Alternatively, the letter's acknowledgment and rejection of gnostic theology may reveal a later date of authorship than orthodox Christianity claims. This can not be assured by a simple study of the context. Gnosticism's beginnings and its relationship to Christianity are poorly dated, due to an insufficient corpus of literature relating the first interactions between the two religions. It vehemently condemns such anti-corporeal attitudes, which also indicates that those taking such unorthodox positions were either sufficiently vocal, persuasive, or numerous enough to warrant rebuttal in this form. Adherents of gnosticism were most numerous during the second and third centuries.[3]

Contents[]

This section possibly contains original research. (June 2016) |

It reads as follows in the American Standard Version:

The elder unto the elect lady and her children, whom I love in truth; and not I only, but also all they that know the truth; for the truth's sake which abideth in us, and it shall be with us for ever:

Grace, mercy, peace shall be with us, from God the Father, and from Jesus Christ, the Son of the Father, in truth and love.

I rejoice greatly that I have found [certain] of thy children walking in truth, even as we received commandment from the Father.

And now I beseech thee, lady, not as though I wrote to thee a new commandment, but that which we had from the beginning, that we love one another.

And this is love, that we should walk after his commandments. This is the commandment, even as ye heard from the beginning, that ye should walk in it.

For many deceivers are gone forth into the world, [even] they that confess not that Jesus Christ cometh in the flesh. This is the deceiver and the antichrist.

Look to yourselves, that ye lose not the things which we have wrought, but that ye receive a full reward.

Whosoever goeth onward and abideth not in the teaching of Christ, hath not God: he that abideth in the teaching, the same hath both the Father and the Son.

If any one cometh unto you, and bringeth not this teaching, receive him not into [your] house, and give him no greeting: for he that giveth him greeting partaketh in his evil works.

Having many things to write unto you, I would not [write them] with paper and ink: but I hope to come unto you, and to speak face to face, that your joy may be made full.

The children of thine elect sister salute thee.

The doctrines of Docetism and Gnosticism had made inroads among the followers of Jesus in the latter half of the First Century. Some said that Jesus never assumed human flesh, but only had the appearance of flesh, because they were scandalized that Divinity would soil itself by associating so closely with matter. Others said that Christ was raised as a spirit only, and did not experience a bodily resurrection. In this epistle John condemns such doctrines in no uncertain terms with the statement that such persons were antichrist.

Interpretation of "The Lady"[]

The text is addressed to "the elect lady and her children" (some interpretations translate this phrase as "elder lady and her children"), and closes with the words, "The children of thy elect sister greet thee." The person addressed is commended for her piety, and is warned against false teachers.

The lady has often been seen as a metaphor for the church, the church being the body of believers as a whole and as local congregations.[4] The children would be members of that local congregation. The writer also includes a greeting from another church in the final verse, "The children of thy elect sister greet thee." The term the elect was a fairly common term for those who believe in the gospel and follow Christ.[5][6][7] Scholar Amos Wilder supports this view, saying the content of the epistle itself shows it was addressed to the church as a whole rather than a single person.[8]

Another interpretation holds that the letter is addressed to a specific individual. Athanasius proposed[9] that Kyria, the Greek word used here which means lady,[10] was actually a name. The Young's Literal Translation of the Bible translates it this way.[11] It is also possible it refers to an individual but simply does not use her name.[9] One theory is that the letter refers to Mary, mother of Jesus; Jesus had entrusted his "beloved disciple" with Mary's life when Jesus was on the cross (John 19:26–27). The children would thus refer to the brothers of Jesus: James, Joses, Simon and Jude, and the sister to Mary's sister mentioned in John 19:25. Mary was likewise never referred to by name in John's gospel. Such an interpretation would assume a much earlier date of composition than modern scholars have suggested.[12][13]

See also[]

- Authorship of the Johannine works

- Textual variants in the New Testament § Second Epistle of John

Notes[]

- ^ John Painter, 1, 2, and 3 John (Sacra Pagina), Volume 18 of Sacra Pagina, Liturgical Press, 2008. pp. 57–59

- ^ James Leslie Houlden, Johannine epistles, Black's New Testament commentaries, Edition 2, Continuum International Publishing Group, 1994. pp. 139–40

- ^ Cf. Bart D. Ehrman. Lost Christianities. Oxford University press, 2003, pp. 116–26

- ^ Burton, Ernest DeWitt (1896). "The Epistles of John". The Biblical World. 7 (5): 368–69. JSTOR 3140373.

- ^ thebereancall.org

- ^ Did Christ Die Only for the Elect?: A Treatise on the extent of Christ's Atonement ISBN 1-57910-135-6 pp. 113–114

- ^ biblegateway.com

- ^ Wilder, Amos. "II John: Exegesis". In Harmon, Nolan (ed.). The Interpreter's Bible. 12. p. 303.

- ^ a b New English Translation (PDF). p. 2 John.

- ^ "κυρίᾳ". Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "2 John 1 YLT". Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ biblicalarchaeology.org

- ^ bible-truth.org

References[]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "John, Second Epistle of". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "John, Second Epistle of". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Online translations of the Second Epistle of John:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

- KJV

- NIV

Bible: 2 John public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: 2 John public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Online articles on the Second Epistle of John:

- Second Epistle of John

- 2nd-century Christian texts

- New Testament books

- Christian anti-Gnosticism

- Catholic epistles

- Johannine literature

- Women in the New Testament

- Antilegomena