Targum

A targum (Aramaic: תרגום 'interpretation, translation, version') was an originally spoken translation of the Hebrew Bible (also called the Tanakh) that a professional translator (מְתוּרגְמָן mǝturgǝmān) would give in the common language of the listeners when that was not Hebrew. This had become necessary near the end of the first century BCE, as the common language was Aramaic and Hebrew was used for little more than schooling and worship.[1] The translator frequently expanded his translation with paraphrases, explanations and examples, so it became a kind of sermon.

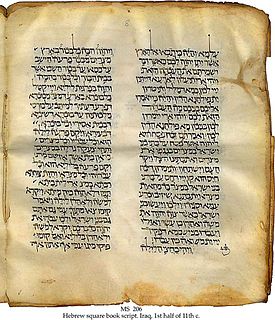

Writing down the targum was initially prohibited; nevertheless, some targumitic writings appeared as early as the middle of the first century CE.[1] They were not then recognized as authoritative by the religious leaders.[1] Some subsequent Jewish traditions (beginning with the Babylonian Jews) accepted the written targumim as authoritative translations of the Hebrew scriptures into Aramaic. Today, the common meaning of targum is a written Aramaic translation of the Bible. Only Yemenite Jews continue to use the targumim liturgically.

As translations, the targumim largely reflect midrashic interpretation of the Tanakh from the time they were written and are notable for favoring allegorical readings over anthropomorphisms.[2] (Maimonides, for one, notes this often in The Guide for the Perplexed.) That is true both for those targums that are fairly literal as well as for those that contain many midrashic expansions. In 1541, Elia Levita wrote and published the Sefer Meturgeman, explaining all the Aramaic words found in the Targum[which?].[3][4]

Targumim are used today as sources in text-critical editions of the Bible (Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia refers to them with the abbreviation