Book of Revelation

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Related literature |

| See also |

The Book of Revelation – also called the Apocalypse of John, Revelation to John or Revelation from Jesus Christ – is the final book of the New Testament, and consequently is also the final book of the Christian Bible. Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: apokalypsis, meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of Revelation is the only apocalyptic book in the New Testament canon.[a] Thus, it occupies a central place in Christian eschatology.

The author names himself as "John" in the text, but his precise identity remains a point of academic debate. Second-century Christian writers such as Papias, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Melito (the bishop of Sardis), Clement of Alexandria, and the author of the Muratorian fragment identify John the Apostle as the "John" of Revelation.[1] [2] Modern scholarship generally takes a different view,[3] with many considering that nothing can be known about the author except that he was a Christian prophet.[4] Modern theological scholars characterize the Book of Revelation's author as "John of Patmos". The bulk of traditional sources date the book to the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (AD 81–96), which evidence tends to confirm.[5][b]

The book spans three literary genres: the epistolary, the apocalyptic, and the prophetic.[7] It begins with John, on the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea, addressing a letter to the "Seven Churches of Asia". He then describes a series of prophetic visions, including figures such as the Seven-Headed Dragon, the Serpent, and the Beast, which culminate in the Second Coming of Jesus.

The obscure and extravagant imagery has led to a wide variety of Christian interpretations. Historicist interpretations see Revelation as containing a broad view of history, whilst preterist interpretations treat Revelation as mostly referring to the events of the Apostolic Age (1st century), or, at the latest, the fall of the Roman Empire. Futurists, meanwhile, believe that Revelation describes future events, with the seven churches growing into the body/believers throughout the age, and a reemergence or continuous rule of a Roman/Graeco system with modern capabilities described by John in ways familiar to him, and idealist or symbolic interpretations consider that Revelation does not refer to actual people or events, but is an allegory of the spiritual path and the ongoing struggle between good and evil.

Composition and setting[]

Title, authorship, and date[]

The name Revelation comes from the first word of the book in Koine Greek: ἀποκάλυψις (apokalypsis), which means "unveiling" or "revelation". The author names himself as "John", but modern scholars consider it unlikely that the author of Revelation also wrote the Gospel of John.[8] He was a Jewish Christian prophet, probably belonging to a group of such prophets, and was accepted by the congregations to whom he addresses his letter.[5][9]

The book is commonly dated to about 95 AD, as suggested by clues in the visions pointing to the reign of the emperor Domitian.[10] The beast with seven heads and the number 666 seem to allude directly to the emperor Nero (reigned AD 54–68), but this does not require that Revelation was written in the 60s, as there was a widespread belief in later decades that Nero would return.[11][5]

Genre[]

Revelation is an apocalyptic prophecy with an epistolary introduction addressed to seven churches in the Roman province of Asia.[4] "Apocalypse" means the revealing of divine mysteries;[12] John is to write down what is revealed (what he sees in his vision) and send it to the seven churches.[4] The entire book constitutes the letter—the letters to the seven individual churches are introductions to the rest of the book, which is addressed to all seven.[4] While the dominant genre is apocalyptic, the author sees himself as a Christian prophet: Revelation uses the word in various forms twenty-one times, more than any other New Testament book.[13]

Sources[]

The predominant view is that Revelation alludes to the Old Testament although it is difficult among scholars to agree on the exact number of allusions or the allusions themselves.[14] Revelation rarely quotes directly from the Old Testament, yet almost every verse alludes to or echoes older scriptures. Over half of the references stem from Daniel, Ezekiel, Psalms, and Isaiah, with Daniel providing the largest number in proportion to length and Ezekiel standing out as the most influential. Because these references appear as allusions rather than as quotes, it is difficult to know whether the author used the Hebrew or the Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures, but he was clearly often influenced by the Greek. He very frequently combines multiple references, and again the allusional style makes it impossible to be certain to what extent he did so consciously.[15][need quotation to verify]

Setting[]

Conventional understanding has been that the Book of Revelation was written to comfort beleaguered Christians as they underwent persecution at the hands of an emperor.

This is not the only interpretation. Domitian may not have been a despot imposing an imperial cult, and there may not have been any systematic empire-wide persecution of Christians in his time.[16][additional citation(s) needed] Revelation may instead have been composed in the context of a conflict within the Christian community of Asia Minor over whether to engage with, or withdraw from, the far larger non-Christian community: Revelation chastises those Christians who wanted to reach an accommodation with the Roman cult of empire.[17] This is not to say that Christians in Roman Asia were not suffering for withdrawal from, and defiance against, the wider Roman society, which imposed very real penalties; Revelation offered a victory over this reality by offering an apocalyptic hope: in the words of professor Adela Yarbro Collins, "What ought to be was experienced as a present reality."[18]

Canonical history[]

Revelation was among the last books accepted into the Christian biblical canon, and to the present day some churches that derive from the Church of the East reject it.[19][20] Eastern Christians became skeptical of the book as doubts concerning its authorship and unusual style[21] were reinforced by aversion to its acceptance by Montanists and other groups considered to be heretical.[22] This distrust of the Book of Revelation persisted in the East through the 15th century.[23]

Dionysius (AD 248), bishop of Alexandria and disciple of Origen, wrote that the Book of Revelation could have been written by Cerinthus although he himself did not adopt the view that Cerinthus was the writer. He regarded the Apocalypse as the work of an inspired man but not of an Apostle (Eusebius, Church History VII.25).[24]

Eusebius, in his Church History (c. 330 AD) mentioned that the Apocalypse of John was accepted as a Canonical book and rejected at the same time:

- 1. ... it is proper to sum up the writings of the New Testament which have been already mentioned... After them is to be placed, if it really seem proper, the Apocalypse of John, concerning which we shall give the different opinions at the proper time. These then belong among the accepted writings [Homologoumena].

- 4. Among the rejected [Kirsopp. Lake translation: "not genuine"] writings must be reckoned, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books.[25]

The Apocalypse of John is counted as both accepted (Kirsopp. Lake translation: "Recognized") and disputed, which has caused some confusion over what exactly Eusebius meant by doing so. The disputation can perhaps be attributed to Origen.[26] Origen seems to have accepted it in his writings.[27]

Cyril of Jerusalem (348 AD) does not name it among the canonical books (Catechesis IV.33–36).[28]

Athanasius (367 AD) in his Letter 39,[29] Augustine of Hippo (c. 397 AD) in his book On Christian Doctrine (Book II, Chapter 8),[30] Tyrannius Rufinus (c. 400 AD) in his Commentary on the Apostles' Creed,[31] Pope Innocent I (405 AD) in a letter to the bishop of Toulouse[32] and John of Damascus (about 730 AD) in his work An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (Book IV:7)[33] listed "the Revelation of John the Evangelist" as a canonical book.

Synods[]

The Council of Laodicea (363) omits it as a canonical book.[34]

The Decretum Gelasianum, which is a work written by an anonymous scholar between 519 and 553, contains a list of books of scripture presented as having been reckoned as canonical by the Council of Rome (382 AD). This list mentions it as a part of the New Testament canon.[35]

The Synod of Hippo (in 393),[36] followed by the Council of Carthage (397), the Council of Carthage (419), the Council of Florence (1442 AD)[37] and the Council of Trent (1546 AD)[38] classified it as a canonical book.[39]

The Apostolic Canons, approved by the Eastern Orthodox Council in Trullo in 692, but rejected by Pope Sergius I, omit it.[40]

Protestant Reformation[]

Doubts resurfaced during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther called Revelation "neither apostolic nor prophetic" in the 1522 preface to his translation of the New Testament (he revised his position with a much more favorable assessment in 1530),[citation needed] Huldrych Zwingli labelled it "not a book of the Bible",[41] and it was the only New Testament book on which John Calvin did not write a commentary.[42] As of 2015 Revelation remains the only New Testament book not read in the Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church,[43] though Catholic and Protestant liturgies include it.[citation needed]

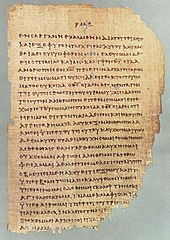

Texts and manuscripts[]

There are approximately 300 Greek manuscripts of Revelation.[44] While it is not extant in Codex Vaticanus (4th century), it is extant in the other great uncial codices: Sinaiticus (4th century), Alexandrinus (5th century), and Ephraemi Rescriptus (5th century). In addition, there are numerous papyri, especially