Epistle of James

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

The Epistle of James, the Letter of James, or simply James (Ancient Greek: Ἰάκωβος, romanized: Iakōbos), is a General epistle and one of the 21 epistles (didactic letters) in the New Testament.

The author identifies himself as "James, a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ" who is writing to "the twelve tribes scattered abroad" (James 1:1). The epistle is traditionally attributed to James the brother of Jesus (James the Just),[1][2] and the audience is generally considered to be Jewish Christians, who were dispersed outside Israel.[3][4]

Framing his letter within an overall theme of patient perseverance during trials and temptations, James writes in order to encourage his readers to live consistently with what they have learned in Christ. He condemns various sins, including pride, hypocrisy, favouritism, and slander. He encourages and implores believers to humbly live by godly, rather than worldly wisdom and to pray in all situations.

For the most part, until the late 20th century, the epistle of James was relegated to benign disregard – though it was shunned by many early theologians and scholars due to its advocacy of Torah observance and good works.[5] Famously, Luther at one time considered the epistle to be among the disputed books, and sidelined it to an appendix,[6] although in his Large Catechism he treated it as the authoritative word of God.[7]

The epistle aims to reach a wide Jewish audience.[8] During the last decades, the epistle of James has attracted increasing scholarly interest due to a surge in the quest for the historical James,[9] his role within the Jesus movement, his beliefs, and his relationships and views. This James revival is also associated with an increasing level of awareness of the Jewish grounding of both the epistle and the early Jesus movement.[10]

Authorship[]

The debate about the authorship of James is inconclusive and shadows debates about Christology, and about historical accuracy.

According to Robert J. Foster, "there is little consensus as to the genre, structure, dating, and authorship of the book of James."[11] There are four "commonly espoused" views concerning authorship and dating of the Epistle of James:[12]

- the letter was written by James before the Pauline epistles,

- the letter was written by James after the Pauline epistles,

- the letter is pseudonymous,

- the letter comprises material originally from James but reworked by a later editor.[13]

The writer refers to himself only as "James, a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ".[14] Jesus had two apostles named James: James, the son of Zebedee and James, the son of Alphaeus, but it is unlikely that either of these wrote the letter. According to the Book of Acts, James, the brother of John, was killed by Herod Agrippa I.[15] James, the son of Alphaeus is a more viable candidate for authorship, although he is not prominent in the scriptural record, and relatively little is known about him. Hippolytus, writing in the early third century, asserted in his work On the 12 Apostles:[16]

And James the son of Alphaeus, when preaching in Jerusalem was stoned to death by the Jews, and was buried there beside the temple.

The similarity of his alleged martyrdom to the stoning of James the Just has led some scholars, such as Robert Eisenman[17] and James Tabor,[18] to assume that these "two Jameses" were one and the same. This identification of James of Alphaeus with James the Just (as well as James the Less) has long been asserted, as evidenced by their conflation in Jacobus de Voragine's medieval hagiography the Golden Legend.[19]

Some have said the authorship of this epistle points to James, the brother of Jesus, to whom Jesus evidently had made a special appearance after his resurrection described in the New Testament as this James was prominent among the disciples.[20][21] James the brother of Jesus was not a follower of Jesus before Jesus died according to John 7:2-5,[22] which states that during Jesus' life "not even his brothers believed in him".[23]: 98

From the middle of the 3rd century, patristic authors cited the epistle as written by James, the brother of Jesus and a leader of the Jerusalem church.[3]

If the letter is of pseudonymous authorship (i.e. not written by an apostle but by someone else), this implies that the person named "James" is respected and doubtless well known. Moreover, this James, brother of Jesus, is honored by the epistle written and distributed after the lifetime of James, the brother of Jesus.[24] Indeed, while not numbered among the Twelve Apostles unless he is identified as James the Less,[25] James was nonetheless a very important figure: Paul the Apostle described him as "the brother of the Lord" in Galatians 1:19 and as one of the three "pillars of the Church" in 2:9."There is no doubt that James became a much more important person in the early Christian movement than a casual reader of the New Testament is likely to imagine."[26] The James believers are acquainted with, emerges out of Galatians 1-2; 1 Corinthians 15-17 and Acts 12,15,21. We also have accounts about James in Josephus, Eusebius, Origen, the Gospel of Thomas, the Apocalypses of James, the Gospel of the Hebrews and the Pseudo-Clementine literature – most of whom cast him as righteous and as the undisputed leader of the Jewish camp.[27] "His influence is central and palpable in Jerusalem and in Antioch, despite the fact that he did not minister at Antioch. Although we are dependent on sources dominated by the Pauline perspective… the role and influence of James overshadow all others at Antioch."[28]

John Calvin and others suggested that the author was the James, son of Alphaeus, who is referred to as James the Less. The Protestant reformer Martin Luther denied it was the work of an apostle and termed it an "epistle of straw".[29]

The Holy Tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church teaches that the Book of James was "written not by either of the apostles, but by the 'brother of the Lord' who was the first bishop of the Church in Jerusalem."[30][4]

Arguments for a pseudepigraphon[]

There is a majority view that it is pseudonymous.[31] Most scholars consider the epistle to be pseudepigrapha because of these factors:[32]

- The author introduces himself merely as "a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ" without invoking any special family relationship to Jesus or even mentioning Jesus widely in the book. (James 1:1)

- The cultured Greek language of the Epistle, it is contended, could not have been written by a Jerusalem Jew. Some scholars argue for a primitive version of the letter composed by James and then later polished by another writer.[33]

- Some see parallels between James and 1 Peter, 1 Clement, and the Shepherd of Hermas and take this to reflect the socio-economic situation Christians were dealing with in the late 1st or early 2nd century. It thus could have been written anywhere in the Empire that Christians spoke Greek. There are some scholars who argued for Syria.[33]

Minority or fringe view[]

Some scholars state James the Just as the author on the following grounds:[34]

- A reverent leader in the early church would not have boasted a familial connection with Jesus, as James could have. Rather, James' recognition of Jesus as "God and Lord"[35] supersedes any familial relationship James had with Jesus.

- The historicity of James is well documented in historical literature.[36][37]

Dating[]

Scholars, such as Luke Timothy Johnson, suggest an early dating for the Epistle of James:

The Letter of James also, according to the majority of scholars who have carefully worked through its text in the past two centuries, is among the earliest of New Testament compositions. It contains no reference to the events in Jesus' life, but it bears striking testimony to Jesus' words. Jesus' sayings are embedded in James' exhortations in a form that is clearly not dependent on the written Gospels.[38]

If written by James the brother of Jesus, it would have been written sometime before AD 69 (or AD 62), when he was martyred.

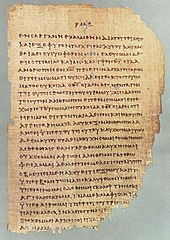

The earliest extant manuscripts of James usually date to the mid-to-late 3rd century.[13]

Dated consensually c. 65–85 CE. The traditional author is James the Just, "a servant of God and brother of the Lord Jesus Christ". Like Hebrews, James is not so much a letter as an exhortation; the style of the Greek language-text makes it unlikely that it was actually written by James, the brother of Jesus. Most scholars regard all the letters in this group as pseudonymous.[31]

Genre[]

James is considered New Testament wisdom literature: "like Proverbs and Sirach, it consists largely of moral exhortations and precepts of a traditional and eclectic nature."[39]

The content of James is directly parallel, in many instances, to sayings of Jesus which are found in the gospels of Luke and Matthew, i.e., those attributed to the hypothetical Q source, in the two-source hypothesis. Compare, for example, "Do not swear at all, either by heaven ... or by the earth ... Let your word be 'Yes, Yes' or 'No, No'; anything more than this comes from the evil one"[40] and " ... do not swear either by heaven or by earth or by any other oath, but let your 'Yes' be yes and your 'No' be no, so that you may not fall under condemnation" (James 5:12). According to James Tabor, the epistle of James contains "no fewer than thirty direct references, echoes, and allusions to the teachings of Jesus found in the Q source."[41]

Koester H. (1965) and Kloppenborg J. (1987) are widely recognized for bringing about the pivot from the above (traditional) emphasis on James as wisdom and ethics literature, to focus on the apocalyptic and pre-Gentile (Jewish) context of James.[42] Later studies strengthened this recent appreciation for the pre-Gentile foundations of Q, M, and James. In addition to James, traces of the Jewish followers of Jesus are to be found in the extra-canonical Jewish Gospels (Nazoraeans, Ebionites),[43] in the Didache[44] and the Pseudo-Clementine literature,[45] texts which are not focused on Jesus' death and resurrection and neither advocate, nor do they seem to advocate, Torah observance.[46]

Structure[]

Some view the epistle as having no overarching outline: "James may have simply grouped together small 'thematic essays' without having more linear, Greco-Roman structures in mind."[47] That view is generally supported by those who believe that the epistle may not be a true piece of correspondence between specific parties but an example of wisdom literature, formulated as a letter for circulation. The Catholic Encyclopedia says, "the subjects treated of in the Epistle are many and various; moreover, St. James not infrequently, whilst elucidating a certain point, passes abruptly to another, and presently resumes once more his former argument."[3]

Others view the letter as having only broad topical or thematic structure. They generally organize James under three (Ralph Martin[48]) to seven (Luke Johnson[49]) general key themes or segments.

A third group believes that James was more purposeful in structuring his letter, linking each paragraph theologically and thematically:

James, like the gospel writers, can be seen as a purposeful theologian, carefully weaving his smaller units together into larger fabrics of thought and using his overall structure to prioritize his key themes.

— Blomberg and Kamell[47]

The third view of the structuring of James is a historical approach that is supported by scholars who are not content with leaving the book as "New Testament wisdom literature, like a small book of proverbs" or "like a loose collection of random pearls dropped in no particular order onto a piece of string."[50]

A fourth group uses modern discourse analysis or Greco-Roman rhetorical structures to describe the structure of James.[51]

The United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament divides the letter into the following sections:

|

|

Historical context[]

A 2013 article in the Evangelical Quarterly explores a violent historical background behind the epistle and offers the suggestion that it was indeed written by James, the brother of Jesus, and it was written before AD 62, the year he was killed.[note 1] The 50s saw the growth of turmoil and violence in Roman Judea, as Jews became more and more frustrated with corruption, injustice and poverty. It continued into the 60s, four years before James was killed. War broke out with Rome and would lead to the destruction of Jerusalem and the scattering of the people. The epistle is renowned for exhortations on fighting poverty and caring for the poor in practical ways (1:26–27; 2:1–4; 2:14–19; 5:1–6), standing up for the oppressed (2:1–4; 5:1–6) and not being "like the world" in the way one responds to evil in the world (1:26–27; 2:11; 3:13–18; 4:1–10). Worldly wisdom is rejected and people are exhorted to embrace heavenly wisdom, which includes peacemaking and pursuing righteousness and justice (3:13–18).[52]

This approach sees the epistle as a real letter with a real immediate purpose: to encourage Christian Jews not to revert to violence in their response to injustice and poverty but to stay focused on doing good, staying holy and to embrace the wisdom of heaven, not that of the world.[53]

Doctrine[]

Justification[]

The epistle contains the following famous passage concerning salvation and justification:

14 What good is it, my brothers, if someone says he has faith but does not have works? Can that faith save him? 15 If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and lacking in daily food, 16 and one of you says to them, “Go in peace, be warmed and filled,” without giving them the things needed for the body, what good is that? 17 So also faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead. 18 But someone will say, “You have faith and I have works.” Show me your faith apart from your works, and I will show you my faith by my works. 19 You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder! 20 Do you want to be shown, you foolish person, that faith apart from works is useless? 21 Was not Abraham our father justified by works when he offered up his son Isaac on the altar? 22 You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was completed by his works; 23 and the Scripture was fulfilled that says, “Abraham believed God, and it was counted to him as righteousness”—and he was called a friend of God. 24 You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. 25 And in the same way was not also Rahab the prostitute justified by works when she received the messengers and sent them out by another way? 26 For as the body apart from the spirit is dead, so also faith apart from works is dead.[54]

This passage has been contrasted with the teachings of Paul the Apostle on justification. Some scholars even believe that the passage is a response to Paul.[55] One issue in the debate is the meaning of the Greek word δικαιόω (dikaiόō) 'render righteous or such as he ought to be',[56] with some among the participants taking the view that James is responding to a misunderstanding of Paul.[57]

Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy have historically argued that the passage disproves the doctrine of justification by faith alone (sola fide).[58][59] The early (and many modern) Protestants resolve the apparent conflict between James and Paul regarding faith and works in alternate ways from the Catholics and Orthodox:[60]

Paul was dealing with one kind of error while James was dealing with a different error. The errorists Paul was dealing with were people who said that works of the law were needed to be added to faith in order to help earn God's favor. Paul countered this error by pointing out that salvation was by faith alone apart from deeds of the law (Galatians 2:16; Romans 3:21–22). Paul also taught that saving faith is not dead but alive, showing thanks to God in deeds of love (Galatians 5:6 ['...since in Christ Jesus it is not being circumcised or being uncircumcised that can effect anything – only faith working through love.']). James was dealing with errorists who said that if they had faith they didn't need to show love by a life of faith (James 2:14–17). James countered this error by teaching that faith is alive, showing itself to be so by deeds of love (James 2:18,26). James and Paul both teach that salvation is by faith alone and also that faith is never alone but shows itself to be alive by deeds of love that express a believer's thanks to God for the free gift of salvation by faith in Jesus.[61]

According to Ben Witherington III, differences exist between the Apostle Paul and James, but both used the law of Moses, the teachings of Jesus and other Jewish and non-Jewish sources, and "Paul was not anti-law any more than James was a legalist".[23]: 157–158 A more recent article suggests that the current confusion regarding the Epistle of James about faith and works resulted from Augustine of Hippo's anti-Donatist polemic in the early fifth century. [62] This approach reconciles the views of Paul and James on faith and works.

Anointing of the Sick[]

The epistle is also the chief biblical text for the Anointing of the Sick. James wrote:

14Is anyone among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord. 15And the prayer of faith will save the one who is sick, and the Lord will raise him up. And if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven.[63]

G. A. Wells suggested that the passage was evidence of late authorship of the epistle, on the grounds that the healing of the sick being done through an official body of presbyters (elders) indicated a considerable development of ecclesiastical organisation "whereas in Paul's day to heal and work miracles pertained to believers indiscriminately (I Corinthians, XII:9)."[64]

Works, deeds and care for the poor[]

James and the M Source material in Matthew are unique in the canon in their stand against the rejection of works and deeds.[65] According to Sanders, traditional Christian theology wrongly divested the term "works" of its ethical grounding, part of the effort to characterize Judaism as legalistic.[66] However, for James and for all Jews, faith is alive only through Torah observance. In other words, belief demonstrates itself through practice and manifestation. For James, claims about belief are empty, unless they are alive in action, works and deeds.[67]

Do not merely listen to the word, and so deceive yourselves. Do what it says. Anyone who listens to the word but does not do what it says is like someone who looks at his face in a mirror and, after looking at himself, goes away and immediately forgets what he looks like. But whoever looks intently into the perfect law that gives freedom, and continues in it-not forgetting what they have heard, but doing it-they will be blessed in what they do."

— James 1:22–25[68]

Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world.

— James 1:27[69]

Speak and act as those who are going to be judged by the law that gives freedom, because judgment without mercy will be shown to anyone who has not been merciful. Mercy triumphs over judgment.

— James 2:12–13[70]

Torah observance[]

James is unique in the canon by its explicit and wholehearted support of Torah-observance (the Law). According to Bibliowicz, not only is this text a unique view into the milieu of the Jewish founders – its inclusion in the canon signals that as canonization began (fourth century onward) Torah observance among believers in Jesus was still authoritative. [71] According to modern scholarship James, Q, Matthew, the Didache, and the pseudo-Clementine literature reflect a similar ethos, ethical perspective, and stand on, or assume, Torah observance. James call to Torah observance (1:22-27) insures salvation (2:12–13, 14–26).[72] Hartin is supportive of the focus on Torah observance and concludes that these texts support faith through action and sees them as reflecting the milieu of the Jewish followers of Jesus (2008).[73] Hub van de Sandt sees Matthew's and James’ Torah observance reflected in a similar use of the Jewish Two Ways theme which is detectable in the Didache too (3:1–6). McKnight thinks that Torah observance is at the heart of James's ethics.[74] A strong message against those advocating the rejection of Torah observance characterizes, and emanates from, this tradition: "Some have attempted while I am still alive, to transform my words by certain various interpretations, in order to teach the dissolution of the law; as though I myself were of such a mind, but did not freely proclaim it, which God forbid! For such a thing were to act in opposition to the law of God which was spoken by Moses, and was borne witness to by our Lord in respect of its eternal continuance; for thus he spoke: 'The heavens and the earth shall pass away, but one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass away from the law.'"[75]

James seem to propose a more radical and demanding interpretation of the law than mainstream Judaism. According to Painter, there is nothing in James to suggest any relaxation of the demands of the law. [76] "No doubt James takes for granted his readers' observance of the whole law, while focusing his attention on its moral demands."[77]

Canonicity[]

The Epistle of James was first explicitly referred to and quoted by Origen of Alexandria,[78] and possibly a bit earlier by Irenaeus of Lyons,[79] although it was not mentioned by Tertullian, who was writing at the end of the Second century.[64]

The Epistle of James was included among the twenty-seven New Testament books first listed by Athanasius of Alexandria in his Thirty-Ninth Festal Epistle (AD 367)[80] and was confirmed as a canonical epistle of the New Testament by a series of councils in the fourth century.

In the first centuries of the Church the authenticity of the Epistle was doubted by some, including Theodore of Mopsuestia in the mid-fifth century. Because of the silence of several of the western churches regarding it, Eusebius classes it among the Antilegomena or contested writings (Historia ecclesiae, 3.25; 2.23). Gaius Marius Victorinus, in his commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians, openly questioned whether the teachings of James were heretical.[81]

Its late recognition in the Church, especially in the West, may be explained by the fact that it was written for or by Jewish Christians, and therefore not widely circulated among the Gentile Churches. There is some indication that a few groups distrusted the book because of its doctrine. In Reformation times a few theologians, most notably Martin Luther in his early ministry,[82] argued that this epistle should not be part of the canonical New Testament.[83][84]

Martin Luther's description of the Epistle of James varies. In some cases, Luther argues that it was not written by an apostle; but in other cases, he describes James as the work of an apostle.[85] He even cites it as authoritative teaching from God[86] and describes James as "a good book, because it sets up no doctrines of men but vigorously promulgates the law of God."[87] Lutherans hold that the Epistle is rightly part of the New Testament, citing its authority in the Book of Concord.[82]

Notes[]

- ^ On the death of James, see Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 20.9.1 and Eusebius II.23.1–18.

See also[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Epistle of James |

- Abrogation of Old Covenant laws

- Gospel of James

- Jacob (name)

- Pauline Christianity

- Textual variants in the Epistle of James

References[]

- ^ Davids, Peter H (1982). The Epistle of James: A Commentary on the Greek Text. New International Greek Testament Commentary (Repr. ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans. ISBN 0802823882.

- ^ Evans, Craig A (2005). Craig A Evans (ed.). Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: John, Hebrews-Revelation. Colorado Springs, Colo.: Victor. ISBN 0781442281.

- ^ a b c Camerlynck, Achille (1910). "Epistle of St James". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Letters of Saint James." Orthodox Church in America, OCA, (n.d.). Accessed 11 Dec. 2018.

- ^ Bibliowicz, Abel M. (2019). Jewish-Christian Relations – The First Centuries (Mascarat, 2019). WA: Mascarat. p. 65-67. ISBN 978-1513616483.

- ^ Johnson, L. T. (2004). Brother of Jesus, Friend of God. Brother of Jesus, Friend of God. p. 176. ISBN 0802809863.

- ^ Luther's Large Catechism, 7th Petition, 122-4

- ^ Painter, John (2005). James and Peter models of leadership and mission in Chilton Bruce & Evans Craig The Missions of James, Peter, and Paul. Leiden, Netherlands.: Brill. p. 209. ISBN 9004141618.

- ^ Chilton B. and Evans C. A. Eds. (2005). "James and the Gentiles in The Missions of James, Peter, and Paul: Tensions in Early Christianity". Supplements to Novum Testamentum (115): 91–142.

- ^ Bibliowicz, Abel M. (2019). Jewish-Christian Relations – The First Centuries (Mascarat, 2019). WA: Mascarat. p. 70-72. ISBN 978-1513616483.

- ^ Foster, Robert J. (23 September 2014). The Significance of Exemplars for the Interpretation of the Letter of James. Mohr Siebeck. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-16-153263-4.

- ^ Dan G. McCartney (1 November 2009). James. Baker Academic. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-0-8010-2676-8.

- ^ a b McCartney, Dan G (2009). Robert W Yarbrough and Robert H Stein (ed.). Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament: James. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0801026768.

- ^ James 1:1

- ^ Acts 12:1–2

- ^ of Rome, Pseudo-Hippolytus. "On the Twelve Apostles" and "On the Seventy Disciples". newadvent.org. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Eisenman, Robert (2002), James, the Brother of Jesus" (Watkins)

- ^ Tabor, James D (2006). The Jesus Dynasty: A New Historical Investigation of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-8723-1.

- ^ de Voragine, Jabobus (1275). "The Life of S. James the Less". Fordham.edu.

- ^ See Matthew 13:55; Acts 21:15–25;1 Corinthians 15:7; and Galatians 1:19, 2:9

- ^ Moo, Douglas J (2000). D A Carson (ed.). The Letter of James. Grand Rapids: Wm B Eerdmans Publishing co. ISBN 0802837301.

- ^ "John 7:2-5". BibleGateway.com. World English Bible . Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Shanks, Hershel and Witherington III, Ben. (2004). The Brother of Jesus: The Dramatic Story & Meaning of the First Archaeological Link to Jesus & His Family. HarperSanFrancisco, CA. Retrieved September 18, 2019. ISBN 978-0060581176.

- ^ Shillington, V. George (2015). James and Paul: The Politics of Identity at the Turn of the Ages. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 65–96. ISBN 978-1-4514-8213-3.

- ^ Bechtel, Florentine. "The Brethren of the Lord". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

His identity with James the Less (Mark 15:40) and the Apostle James, the son of Alpheus (Matthew 10:3; Mark 3:18), although contested by many Protestant critics, may also be considered as certain.

- ^ Martin, Ralph P. (1988). James, WBC 48. Waco, Tex.: Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 0849902479.

- ^ Bauckham, Richard (2007). Leadership in James and the Jerusalem Community in Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik, eds., Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries. Peabody, Mass.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 66-70. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- ^ Bibliowicz, Abel M. (2019). Jewish-Christian Relations – The First Centuries (Mascarat, 2019). WA: Mascarat. p. 70-72. ISBN 978-1513616483.

- ^ "HISTORY OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH*". www.ccel.org.

- ^ see Acts 15, Galatians 1:19

- ^ a b Perkins 2012, pp. 19ff.

- ^ "Epistle of James". Early Christian Writings. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ a b John Barton and John Muddiman, ed. (2001). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1256. ISBN 0198755007.

- ^ "Introduction to the Book of James". ESV Study Bible. Crossway. 2008. ISBN 978-1433502415.

- ^ James 1:1

- ^ Josephus, "Jewish Antiquities" 20.200–201

- ^ Eusebius, "Ecclesiastical History" 2.23

- ^ Johnson, Luke Timothy (1996). The Real Jesus. HarperOne. p. 121. ISBN 0060641665.

- ^ Laws, Sophie (1993). The HarperCollins Study Bible. San Francisco: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 2052. ISBN 0060655267.

- ^ Matthew 5:34, 37

- ^ Tabor, James D. (2012). Paul and Jesus: How the Apostle Transformed Christianity. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4391-2332-4.

- ^ Koester, H. (1965). "ΓΝΩΜΑΙ ΔΙΑΦΟΡΟΙ.: The Origin and Nature of Diversification in the History of Early Christianity". HTR. 58 (3): 279–318. doi:10.1017/S0017816000031400.

- ^ Skarsaune, Oskar (2007). The Ebionites in Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik, eds., Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries. Peabody, Mass.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 419-463. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- ^ Draper Jonathan A. and Jefford Clayton N. (2015). The Didache: A Missing Piece of the Puzzle in Early Christianity. Atlanta, GA: SBLECL. p. 14. ISBN 978-1628370485.

- ^ Graham, Graham (2007). Christian Elements in the Pseudo-Clementine Writings in Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik, eds., Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries. Peabody, Mass.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 305-323. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- ^ Bibliowicz, Abel M. (2019). Jewish-Christian Relations – The First Centuries (Mascarat, 2019). WA: Mascarat. p. ????. ISBN 978-1513616483.

- ^ a b Blomberg, Craig (2008). James. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 23. ISBN 9780310244028.

- ^ Martin, Ralph (1988). James. Waco, TX: WBC. p. xcviii – civ.

- ^ Johnson, Luke (2000). The Letter of James. Grand Rapids: Pillar. pp. 11–16.

- ^ Some numerous writers and commentators assume so, like William Barclay, The Daily Study Bible, rev. ed., 17 vols. (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1976), Vol 14, The Letters of James and Peter, p. 28.

- ^ Taylor, Mark (2006). A Linguistic Investigation into the Discource Structure of James. London: T&T Clark. ISBN 9780310244028.

- ^ Reiher, Jim (July 2013). "Violent Language – a clue to the Historical Occasion of James". Evangelical Quarterly. LXXXV (3) – via Jim Reiher's Writings.

- ^ Numerous studies argue for a letter- structure to James. See, for example, Euan Fry, "Commentaries on James, I and 2 Peter, and Jude," The Bible Translator, 41 (July 1990): 330, and F.O. Francis, "The Form and Function of the Opening and Closing Paragraphs of James and I John," ZNW 61 (1970):110–126.

- ^ James 2:14–26

- ^ McKnight, Scot (2011). The Letter of James. The New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Erdmans. pp. 259–263. ISBN 978-0-8028-2627-5.

- ^ "Dikaioo". Greek Lexicon. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Martin, D. 2009. New Testament History & Literature: 18. Arguing with Paul. Yale University.

- ^ "The Theological Virtues: 1815". Catechism of the Catholic Church.

The gift of faith remains in one who has not sinned against it. But 'faith apart from works is dead':[Jas 2:26] when it is deprived of hope and love, faith does not fully unite the believer to Christ and does not make him a living member of his Body.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1877). "The Synod of Jerusalem and the Confession of Dositheus, A.D. 1672: Article XIII". Creeds of Christendom. Harper & Brothers.

Man is justified, not by faith alone, but also by works.

- ^ Calvin, John. "James 2:20–26". Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles.

When, therefore, the Sophists set up James against Paul, they go astray through the ambiguous meaning of a term.

- ^ "Faith and Works". WELS Topical Q&A. Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth (2020). "Reading James 2:18–20 with Anti-Donatist Eyes: Untangling Augustine's Exegetical Legacy". Journal of Biblical Literature. 139 (2): 389–410.

- ^ James 5:14–15

- ^ a b Wells, George Albert (1971). The Jesus of Early Christians. London: Pemberton. p. 152. ISBN 0301710147.

- ^ Hagner, Donald A. (2007). Paul as a Jewish Believer in Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik, eds., Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries. Peabody, Mass.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 96-120. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- ^ Sanders, P. (1977). Paul and Palestinian Judaism. Fortress Press. p. 236. ISBN 1506438148.

- ^ Hartin, Patrick J. (2015). "The Letter of James: Faith Leads to Action". Word & World. 35 (3): 229.

- ^ James 1:22–25

- ^ James 1:27

- ^ James 2:12–13

- ^ Bibliowicz, Abel M. (2019). Jewish-Christian Relations – The First Centuries (Mascarat, 2019). WA: Mascarat. p. 70-73. ISBN 978-1513616483.

- ^ Bauckham, Richard (2007). James and the Jerusalem Community in Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik, eds., Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries. Peabody, Mass.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 64-95. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- ^ Hartin, Patrick J. (2008). Law and Ethics in Matthew's Antitheses and James's Letter van de Sandt, Huub and Zangenberg, eds. Introduction in Matthew, James and the Didache. Atlanta, GA: SBL. p. 315,365. ISBN 978-1589833586.

- ^ McKnight, Scot (2011). The Letter of James in New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. p. 34-6. ISBN 978-0802826275.

- ^ Matthew 5:18

- ^ Chilton B. and Evans C. A. Eds. (2005). "James and the Gentiles in The Missions of James, Peter, and Paul: Tensions in Early Christianity". Supplements to Novum Testamentum (115): 222.

- ^ Bauckham, Richard (2001). James and Jesus in The brother of Jesus in James the Just and his mission, eds. Chilton Bruce and Neusner Jacob. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 1105. ISBN 0664222994.

- ^ Aymer, Margaret (12 January 2017). James: An Introduction and Study Guide: Diaspora Rhetoric of a Friend of God. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-00885-4.

- ^ Davis, Glenn (2010). "Irenaeus of Lyons". The Development of the Canon of the New Testament. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Griggs, C Wilfred (1991). Early Egyptian Christianity (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Academic Publisher. p. 173. ISBN 9004094075.

- ^ 1958–, Cooper, Stephen Andrew (24 March 2005). Marius Victorinus' "Commentary on Galatians" : introduction, translation, and notes. Oxford University Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 0198270275. OCLC 878694940.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b The Lutheran Study Bible, Concordia Publishing House, 2009, p2132

- ^ Schaff, Philip. History of the Reformation.

The most important example of dogmatic influence in Luther's version is the famous interpolation of the word alone in Rom. 3:28 (allein durch den Glauben), by which he intended to emphasize his solifidian doctrine of justification, on the plea that the German idiom required the insertion for the sake of clearness.464 But he thereby brought Paul into direct verbal conflict with James, who says (James 2:24), "by works a man is justified, and not only by faith" ("nicht durch den Glauben allein"). It is well known that Luther deemed it impossible to harmonize the two apostles in this article, and characterized the Epistle of James as an "epistle of straw," because it had no evangelical character ("keine evangelische Art").

- ^ Stonehouse, Ned B (1957). Paul Before the Areopagus. pp. 186–197.

- ^ Die deutsche Bibel 41:578-90

- ^ Luther's Large Catechism, IV 122-24

- ^ Luther's Works (American Edition) 35:395

Bibliography[]

- Davids, Peter H. (1982). The Epistle of James: a commentary on the Greek text. The New International Greek Testament Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823885.

- Johnson, Luke Timothy (2007). The Letter of James. Anchor Bible Commentaries. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300139907.

- Perkins, Pheme (2012). Reading the New Testament: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809147861.

External links[]

Bible: James public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: James public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions Quotations related to Epistle of James at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Epistle of James at Wikiquote

- Epistle of James

- Catholic epistles

- New Testament books

- Antilegomena

- James, brother of Jesus