Gospel of James

The Gospel of James (or the Protoevangelium of James)[Notes 1] is a 2nd-century infancy gospel telling of the miraculous conception of the Virgin Mary, her upbringing and marriage to Joseph, the journey of the holy couple to Bethlehem, the birth of Jesus, and events immediately following.[1][2] It is the earliest surviving assertion of the perpetual virginity of Mary, meaning her virginity not just prior to the birth of Jesus, but during and afterwards,[3] and, despite being condemned by Pope Innocent I in 405 and rejected by the Gelasian Decree around 500, became a widely influential source for Mariology.[4][5]

Composition[]

| Gospel of James | |

|---|---|

| Date | Second half of 2nd century AD |

| Attribution | James, brother of Jesus |

| Location | Probably Syria |

| Sources | |

| Manuscripts | Originally Greek |

| Audience | Christian |

| Theme | Sanctity of Mary, her virginity before, during and after the birth of Jesus |

Background: Jesus in early Christianity[]

Early Christianity was not monolithic in its teachings, and the New Testament's views on Jesus verge on the contradictory: some passages, such as the genealogies in Matthew and Luke, emphasise his Davidic descent and take his humanity for granted, while others, such as the prologue to John ("In the beginning was the Word") point to his divinity. What was to become the orthodox position managed to combine the human and divine natures, but at the extremes were those like the Ebionites, who believed that Jesus was entirely human, and the Marcionites, who held that he was entirely divine and that his Earthly career was purely an appearance – the latter idea is known as docetism. Apocryphal literature of the 2nd century, of which the Gospel of James is a leading example, tended towards docetism, particularly regarding the birth and infancy of Jesus, and as a result rejected the idea that he could have had a normal human birth.[6][7]

Date, authorship and sources[]

The Gospel of James was well known to Origen in the early 3rd century and probably to Clement of Alexandria at the end of the 2nd, and so is assumed to have been in circulation soon after c.150 AD.[8] The author claims to be James the half-brother of Jesus by an earlier marriage of Joseph, but in fact his identity is unknown.[9] Early studies assumed a Jewish milieu, largely because of its frequent use and knowledge of the Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures); further investigation demonstrated that it misunderstands and/or misrepresents many Jewish practices, but Judaism at this time was highly diverse, and recent trends in scholarship do not entirely dismiss a Jewish connection.[10] Its origin is probably Syrian, and it possibly derives from a sect called the Encratites,[4] whose founder, Tatian, taught that sex and marriage were symptoms of original sin.[11]

The gospel is a midrash (an elaboration) on the birth narratives found in the gospels of Matthew and Luke,[12] and many of its elements, notably its very physical description of Mary's pregnancy and the examination of her hymen by the midwife Salome, suggest strongly that it was attempting to deny the arguments of docetists and Marcionites, unorthodox Christians who held that Jesus was entirely supernatural.[13] It also draws heavily on the Septuagint version of the Jewish Bible (a Greek translation made in the last centuries before the modern era) for historical analogies, turns of phrase, and details of Jewish life. Ronald Hock and Mary F. Foskett have drawn attention to the influence of Greco-Roman literature on its themes of virginity and purity.[14]

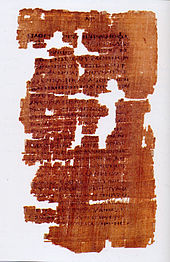

Manuscripts and manuscript tradition[]

Scholars generally accept that the Gospel of James was originally composed in Greek.[15] Over a hundred Greek manuscripts have survived, and translations were made into Syriac, Ethiopian, Coptic, Georgian, Old Church Slavonic, Armenian, Arabic, and presumably Vulgar Latin, given that it was apparently known to the compiler of the Gelasian Decree.[12] The oldest is Papyrus Bodmer 5 from the 4th or possibly 3rd century, discovered in 1952 and now in the Bodmer Library, Geneva, while the fullest is a 10th-century Greek codex in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.[1][16] Emile de Stryker published the standard modern critical edition in 1961, and in 1995 Ronald Hock published an English translation based on de Stryker.[17]

Structure and content[]

The narrative is made up of three distinct sections with only slight ties to each other:

- Chapters 1–17: A biography of Mary, dealing with her miraculous birth and holy infancy and childhood, her engagement to Joseph and virginal conception of Jesus;

- Chapters 18–20: The birth of Jesus, including proof that Mary continued to be a virgin even after the birth;

- Chapters 22–24: The death of Zacharias, father of John the Baptist.[18]

Mary is presented as an extraordinary child destined for great things from the moment of her conception.[1] Her parents, the wealthy Joachim and his wife Anna (or Anne), are distressed that they have no children, and Joachim goes into the wilderness to pray, leaving Anna to lament her childless state.[2] God hears Anna's prayer, angels announce the coming child, and in the seventh month of Anna's pregnancy (underlining the exceptional nature of Mary's future life) she is born.[19][2] Anna dedicates the child to God and vows that she shall be raised in the Temple.[2] Joachim and Anna name the child Mary, and when she is three years old they send her to the Temple,[2] where she is fed each day by an angel.[18]

When Mary approaches her twelfth year the priests decide that she can no longer stay in the Temple lest her menstrual blood render it unclean, and God finds a widower, Joseph, to act as her guardian:[2] Joseph is depicted as elderly and the father of grown sons; he has no desire for sexual relations with Mary.[20] He leaves on business, and Mary is called to the Temple to help weave the temple curtain, where one day an angel appears and tells her that she has been chosen to conceive Jesus the Saviour, but that she will not give birth as other women do.[21] Joseph returns and finds Mary six months pregnant, and rebukes her, fearing that the priests will assume that he is the guilty party.[22] They do, but the chastity of both is proven through the "test of bitter waters".[23]

The Roman census forces the holy couple to travel to Bethlehem, but Mary's time comes before they can reach the village.[24] Joseph settles Mary in a cave, where she is guarded by his sons, while he goes in search of a midwife, and for an apocalyptic moment as he searches all creation stands still.[22] He returns with a midwife, and as they stand at the mouth of the cave a cloud overshadows it, an intense light fills it, and there is suddenly a baby at Mary's breast.[22] Joseph and the midwife marvel at the miracle, but a second midwife named Salome (the first is not given a name) insists on examining Mary, upon which her hand withers as a sign of her lack of faith; Salome prays to God for forgiveness and an angel appears and tells her to touch the Christ Child, upon which her hand is healed.[25]

The gospel concludes with the visit of the Three Magi, the massacre of the innocents in Bethlehem, the martyrdom of the High Priest Zechariah (father of John the Baptist), and the election of his successor Simeon,[24] and an epilogue, telling the circumstances under which the work was supposedly composed.[18]

Influence[]

Christianity[]

The Gospel of James was a widely influential source for Christian doctrine regarding Mary.[4][5] Most notably it is the earliest assertion of her perpetual virginity, meaning her virginity not just prior to the birth of Jesus, but during the birth and afterwards.[26] In this it is practically unique in the first three centuries of Christianity, the concept being virtually absent before the 4th century apart from this gospel and the works of Origen.[27] Its explanation of the gospels' "brothers of Jesus" (the adelphoi) as the offspring of Joseph by an earlier marriage remains the position of the Eastern church,[26][28] but in the West the influential theologian Jerome asserted that Joseph himself had been a perpetual virgin, and that the adelphoi were cousins of the Lord rather than half-brothers.[26] It was thanks to Jerome that the Protoevangelium was condemned by Pope Innocent I in 405 and rejected by the Gelasian Decree around 500,[29] but despite being officially condemned it was taken over almost in toto by another apocryphal work , the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which popularised most of its stories.[18]

The gospel was the first to give the name Anne to the mother of Mary, taking it probably from Hannah, the mother of the prophet Samuel, and Mary, like Samuel, is taken to spend her childhood in the temple.[30] Some manuscripts say of Anne's pregnancy that it was the result of normal intercourse with her husband, but current scholars prefer the oldest texts, which say that Mary was conceived in Joachim's absence through divine intervention; nevertheless, the Protoevangelium does not advance the doctrine of Mary's Immaculate Conception.[31]

Various manuscripts place the birth of Mary in the sixth, seventh, eighth or ninth month, with the oldest having the seventh; this was in keeping with both the Judaism of the period, which had similar seventh-month births for significant individuals such as Samuel, Isaac, and Moses, as the sign of a miraculous or divine conception.[31] Further signs of Mary's supremely holy nature follow, including Anne's vow that the infant would never walk on the earth (her bedroom is made a "sanctuary" where she is attended by "undefiled daughters of the Hebrews"), her blessing "with the ultimate blessing" by the priests on her first birthday with the declaration that because of her God will bring redemption to Israel, and the angels who bring her food in the Temple, where she is attended by the priests and engages herself in weaving the temple curtain.[31]

The test of bitter water serves to defend Jesus against accusation of illegitimacy levied in the 2nd century by pagan and Jewish opponents of Christianity.[3][32] Christian sensitivity to these charges made them eager to defend both the virgin birth of Jesus and the immaculate conception of Mary (i.e., her freedom from sin at the moment of her conception).[33]

Islam[]

The Quranic stories of the Virgin Mary and the birth of Jesus are similar to those of the Protoevangelium, which was widely known in the Near East.[34] These include its mention of Mary fed by angels, the choice of her guardian (Joseph) through the casting of lots, and her occupation making a curtain for the Temple immediately before the Annunciation.[35] Nevertheless, while the Quran holds Mary in high esteem and modern Muslims agree with Christians that she was a virgin when she conceived Jesus, they would see the idea of her perpetual virginity (which is the central idea of James) as contrary to the Islamic ideal of women as wives and mothers.[36]

See also[]

- Acts of the Apostles (genre)

- Apocalyptic literature

- Castelseprio – early fresco depiction of the Trial by water

- Gospel

- History of Joseph the Carpenter

- List of Gospels

- List of New Testament papyri

- New Testament apocrypha

- Pseudepigraphy

- Perpetual virginity of Mary

- Salome (Gospel of James)

- Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate

Notes[]

- ^ The original title was "The Birth of Mary"; it has many names, including the "Infancy Gospel of James", the "Story of the Birth of Saint Mary, Mother of God", and "The Birth of Mary, The Revelation of James". See Ehrman, "Lost Scriptures".

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gambero 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Betsworth 2015, p. 166.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burkett 2019, p. 242.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hunter 1993, p. 63.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aquilina & Gruber, p. 35.

- ^ Weaver 2008, p. 351.

- ^ Behr 2008, p. 202.

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Elliott 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Vuong 2019, p. 21-22.

- ^ Hunter 2008, p. 412.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Elliott 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Vuong 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Vuong 2013, p. 14-16.

- ^ Vuong 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Vuong 2013, p. 6-9.

- ^ Vuong 2013, p. 6-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ehrman & Plese 2011, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Gambero 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 448.

- ^ Vuong 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Betsworth 2015, p. 167.

- ^ Gambero 1999, p. 35-40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gambero 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Booton 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lohse 1966, p. 200.

- ^ Hunter 1993, p. 69.

- ^ Vuong 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Betsworth 2015, p. 169.

- ^ Nixon 2004, p. 11-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Shoemaker 2016, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Siker 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Siker 2015, p. 81.

- ^ Bell 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Robinson 1991, p. 19.

- ^ George-Tvrtkovic 2018, p. unpaginated.

Bibliography[]

- Aquilina, Mike; Gruber, Frederick (2015). Keeping Mary Close: Devotion to Our Lady through the Ages. Cincinnati, OH: Servant. p. 35. ISBN 978-1616368746. OCLC 903675818.

- Bauckham, Richard (2015). Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781474230476.

- Behr, John (2008). "Docetism". In Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (eds.). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224165.

- Bell, Richard (2012). The Origin of Islam in Its Christian Environment. Routledge. ISBN 9781136260674.

- Betsworth, Sharon (2015). Children in early Christian literature. T & T Clark. ISBN 9780567657350.

- Booton, Diane E. (2004). "Variations on a Limbourg Theme". In DuBruck, Edelgard E.; Gusick, Barbara I. (eds.). Fifteenth Century Studies. 29. Camden House. ISBN 9781571132963.

- Burkett, Delbert (2019). An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107172784.

- Ehrman, Bart; Plese, Zlatko (2011). The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199831289.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2003). Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament. Oxford University Press.

- Elliott, James Keith (2005). The Apocryphal New Testament: A collection of apocryphal Christian literature in an English translation. Clarendon Press.

- Gambero, Luigi (1999). Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought. Ignatius Press. ISBN 9780898706864.

- George-Tvrtkovic, Rita (2018). Christians, Muslims, and Mary: A History. Paulist Press. ISBN 9781587686764.

- Hunter, David G. (2008). "Marriage, early Christian". In Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (eds.). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224165.

- Hunter, David G. (Spring 1993). "Helvidius, Jovinian, and the Virginity of Mary in Late Fourth-Century Rome". Journal of Early Christian Studies. Johns Hopkins University Press. 1 (1): 47–71. doi:10.1353/earl.0.0147. S2CID 170719507. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- Hurtado, Larry (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802831675.

- Lohse, Bernhard (1966). A Short History of Christian Doctrine. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451404234.

- Maunder, Chris (2019). "Mary and the Gospel Narratives". In Maunder, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198792550.

- Nixon, Virginia (2004). Mary's Mother: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Europe. Penn State Press. ISBN 0271024666.

- Robinson, Neal (1991). Christ in Islam and Christianity. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791405581.

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. (2016). Mary in Early Christian Faith and Devotion. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300219531.

- Siker, Jeffrey S. (2015). Jesus, Sin, and Perfection in Early Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316404669.

- Vuong, Lily C. (2013). Gender and Purity in the Protevangelium of James. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161523373.

- Vuong, Lily C. (2019). The Protevangelium of James. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781532656170.

- Weaver, Rebecca (2008). "Jesus in Early Christianity". In Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (eds.). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224165.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Early Christian Writings website: Infancy Gospel of James

- The Protoevangelium of James: based on the Greek text of Ronald F. Hock

- The Protoevangelium of James: based on the critical Greek text of Émile de Strycker.

- Protoevangelium Jacobi: in Greek.

- Apocryphal Gospels

- 2nd-century Christian texts

- Infancy Gospels

- Pseudepigraphy