Epistle to the Laodiceans

The Epistle to the Laodiceans is a lost (although witnessed in Codex Fuldensis) letter of Paul the Apostle, the original existence of which is inferred from an instruction to the congregation in Colossae to send their letter to the believing community in Laodicea, and likewise obtain a copy of the letter "from Laodicea" (Greek: ἐκ Λαοδικείας, ek Laodikeas).[1]

And when this letter has been read to you, see that it is also read before the church at Laodicea, and that you yourselves read the letter which will be forwarded from there.

— Colossians 4:16 OEB

Several ancient texts purporting to be the missing "Epistle to the Laodiceans" have been known to have existed, most of which are now lost. These were generally considered, both at the time[when?] and by modern scholarship, to be attempts to supply a forged copy of a lost document.[2] The exception is a Latin Epistola ad Laodicenses ("Epistle to the Laodiceans"),[3] which is actually a short compilation of verses from other Pauline epistles, principally Philippians, and on which scholarly opinion is divided as to whether it is the lost Marcionite forgery or alternatively an orthodox replacement of the Marcionite text. In either case it is generally considered a "clumsy forgery" and an attempt to seek to fill the "gap" suggested by Colossians 4:16.[4]

Some ancient sources, such as Hippolytus, and some modern scholars consider that the epistle "from Laodicea" was never a lost epistle, but simply Paul re-using one of his other letters (the most common candidate is the contemporary Epistle to the Ephesians), just as he asks for the copying and forwarding of the Letter to Colossians to Laodicea.

The Colossians 4:16 mention[]

Paul, the earliest known Christian author, wrote several letters (or epistles) in Greek to various churches. Paul apparently dictated all his epistles through a secretary (or amanuensis), but wrote the final few paragraphs of each letter by his own hand.[5][6] Many survived and are included in the New Testament, but others are known to have been lost. The Epistle to the Colossians states "After this letter has been read to you, see that it is also read in the church of the Laodiceans and that you in turn read the letter from Laodicea."[7] The last words can be interpreted as "letter written to the Laodiceans", but also "letter written from Laodicea". The New American Standard Bible (NASB) translates this verse in the latter manner, and translations in other languages such as the Dutch Statenvertaling translate it likewise: "When this letter is read among you, have it also read in the church of the Laodiceans; and you, for your part read my letter (that is coming) from Laodicea."[8][9] Those who read here "letter written to the Laodiceans" presume that, at the time that the Epistle to the Colossians was written, Paul also had written an epistle to the community of believers in Laodicea.[citation needed]

Identification with the Epistle to the Ephesians[]

Some scholars have suggested that this refers to the canonical Epistle to the Ephesians, contending that it was a circular letter (an encyclical) to be read to many churches in the Laodicean area.[10] Others dispute this view.[11]

The Marcionite Epistle to the Laodiceans[]

According to the Muratorian fragment, Marcion's canon contained an epistle called the Epistle to the Laodiceans which is commonly thought to be a forgery written to conform to his own point of view. This is not at all clear, however, since none of the text survives.[12] It is not known what this letter might have contained. Some scholars suggest it may have been the Vulgate epistle described below,[13] while others believe it must have been more explicitly Marcionist in its outlook.[2] Others believe it to be the Epistle to the Ephesians.[14]

The Latin Vulgate Epistle to the Laodiceans[]

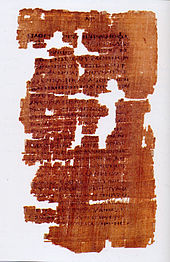

For centuries some Western Latin Bibles used to contain a small Epistle from Paul to the Laodiceans.[15] The oldest known Bible copy of this epistle is in a Fulda manuscript written for Victor of Capua in 546. It is mentioned by various writers from the fourth century onwards, notably by Pope Gregory the Great, to whose influence may ultimately be due the frequent occurrence of it in Bibles written in England; for it is more common in English Bibles than in others. John Wycliffe included Paul's letter to the Laodiceans in his Bible translation from the Latin to English. However this epistle is not without controversy because there is no evidence of a Greek text.[16]

The epistle consists of twenty verses, and is described by Professors Rudolf Knopf (1874-1920) and Gustav Kruger (1862-1940) as "nothing other than a worthless patching together of [canonical] Pauline passages and phrases, mainly from the Epistle to the Philippians."[17] The text was almost unanimously considered pseudepigraphal when the Christian Biblical canon was decided upon, and does not appear in any Greek copies of the Bible at all, nor is it known in Syriac or other versions.[18] Jerome, who wrote the Latin Vulgate translation, wrote in the 4th century, "it is rejected by everyone".[19] It was the opinion of M.R. James that "It is not easy to imagine a more feebly constructed cento of Pauline phrases."[20] However, it evidently gained a certain degree of respect, having appeared in over 100 surviving early Latin copies of the Bible. According to Biblia Sacra iuxta vulgatam versionem, there are Latin Vulgate manuscripts containing this epistle dating between the 6th and 12th century, including Latin manuscripts F (Codex Fuldensis), M, Q, B, D (Ardmachanus), C, and Lambda.[21]

The apocryphal epistle is generally considered a transparent attempt to supply this supposed lost sacred document. Some scholars suggest that it was created to offset the popularity of the Marcionite epistle.[2]

Wilhelm Schneemelcher's standard work, New Testament Apocrypha (Volume 2, Chapter 14 Apostolic Pseudepigrapha) includes a section on the Latin Epistle to the Laodiceans and a translation of the Latin text.[22]

References[]

- ^ Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bart D. Ehrman (2005-09-15). Lost Christianities: The Battles For Scripture And The Faiths We Never Knew. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- ^ Michael D. Marlowe, Bible Research website, The Epistle to the Laodiceans, published October 2010, accessed 8 February 2018

- ^ Miracle and mission Page 151 James A. Kelhoffer - 2000 "Schneemelcher writes of this letter, "It is a rather clumsy forgery, the purpose of which is to have in the Pauline corpus the Epistle of the Laodiceans mentioned in Col. 4:16" (NTApo, 2.44)."

- ^ Harris, p. 316-320. Harris cites Galatians 6:11, Romans 16:22, Colossians 4:18, 2 Thessalonians 3:17, Philemon 19

- ^ Joseph Barber Lightfoot in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians writes: "At this point[Gal. 6:11] the apostle takes the pen from his amanuensis, and the concluding paragraph is written with his own hand. From the time when letters began to be forged in his name([2 Thes. 2:2]; 2 Thes. 3:17) it seems to have been his practice to close with a few words in his own handwriting, as a precaution against such forgeries... In the present case he writes a whole paragraph, summing up the main lessons of the epistle in terse, eager, disjointed sentences. He writes it, too, in large, bold characters (Gr. pelikois grammasin), that his handwriting may reflect the energy and determination of his soul."

- ^ Colossians 4:16, NIV translation

- ^ "NASB translation". Blueletterbible.org. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ Statenvertaling, (Jongbloed <=> 1637 edd.)

- ^ See, for example: Theodore Beza, Novum Testamentum, cum versione Latina veteri, et nova Theodori Bezæ; James Ussher, Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti; and modern scholars John Lightfoot, Fenton John Anthony Hort, Douglas Campbell, and others.

- ^ See, for instance: N. A. Dahl, Theologische Zeitschrift 7 (1951); and W. G. Kummel, et al., Introduction to the New Testament.

- ^ "The Muratorian fragment". Earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ See, e.g. Adolf von Harnack

- ^ Adrian Cozad. "Book Seven of the Apostolicon: The Epistle of the Apostle Paul To the Laodiceans" (PDF). Marcionite Research Library. Melissa Cutler. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ See Latin text here [1], with a translation in Modern English by Michael Marlowe and the Wycliffe Bible translation in Middle English.

- ^ M.R. James, Epistle to the Laodiceans Archived 2006-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, translation and commentary

- ^ Quoted in .Wilhelm Shneermelcher, ed., Edgar Hennecke, New Testament Apocrypha (1965, Philadelphia, Westminster Press) vol. 2,, vol. 2, page 129. The text, with each verse identified, is in Wilhelm Shneermelcher, ed., Edgar Hennecke, New Testament Apocrypha (1965, Philadelphia, Westminster Press) vol. 2, pages 131-132.

- ^ Paul's Epistle to the Laodiceans from The Reluctant Messenger

- ^ Jerome, Lives of Illustrious Men, Chapter 5.

- ^ Montague Rhodes James, The Apocryphal New Testament (1924, Oxford, Clarendon Press) page 479.

- ^ Biblia Sacra Iuxta Vulgatam Versionem, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, vierte, verbesserte Auflage, 1994, p. 1976.

- ^ Wilhelm Schneemelcher; Robert McLachlan Wilson; R. McL. Wilson (2003-06-01). New Testament Apocrypha, Volume Two: Writings Relating to the Apostles; Apocalypses and Related Subjects. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-664-22722-7.

External links[]

Works related to Bible (Wycliffe)/Laodicensis at Wikisource

Works related to Bible (Wycliffe)/Laodicensis at Wikisource

- 1st-century Christian texts

- Apocryphal epistles

- Pauline epistles

- Christian terminology

- Lost religious texts