Epistle of Barnabas

The Epistle of Barnabas (Greek: Βαρνάβα Ἐπιστολή) is a Greek epistle written between AD 70 and 132. The complete text is preserved in the 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus, where it appears immediately after the New Testament and before the Shepherd of Hermas. For several centuries it was one of the "antilegomena" writings that some Christians looked on as sacred scripture, while others excluded them. Eusebius of Caesarea classified it as such. It is mentioned in a perhaps third-century list in the sixth-century Codex Claromontanus and in the later Stichometry of Nicephorus appended to the ninth-century Chronography of Nikephoros I of Constantinople. Some early Fathers of the Church ascribed it to the Barnabas who is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles, but it is now generally attributed to an otherwise unknown early Christian teacher, perhaps of the same name. It is distinct from the Gospel of Barnabas.

Manuscript tradition[]

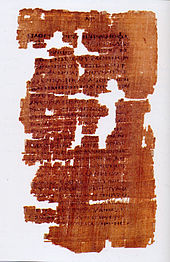

The 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus (S), discovered by Constantin von Tischendorf in 1859 and published by him in 1862, contains a complete text of the Epistle placed after the canonical New Testament and followed by the Shepherd of Hermas. The 11th-century Codex Hierosolymitanus (H), which also includes the Didache, the two Epistles of Clement and the longer version of the Letters of Ignatius of Antioch, is another witness to the full text. It was discovered by Philotheos Bryennios at Constantinople in 1873 and published by him in 1875. Adolf Hilgenfeld used it for his 1877 edition of the Epistle of Barnabas. A family of 10 or 11 manuscripts dependent on the 11th-century Codex Vaticanus graecus 859 (G) contain chapters 5:7b−21:9 placed as a continuation of a truncated text of Polycarp's letter to the Philippians (1:1–9:2). An old Latin version (L), perhaps of no later than the end of the 4th century, that is preserved in a single 9th-century manuscript (St Petersburg, Q.v.I.39) gives the first 17 chapters (without the Two Ways section of chapters 18 to 21) This is a fairly literal rendering in general, but is sometimes significantly shorter than the Greek text. S and H generally agree on readings. G often agrees with L against S and H. A small papyrus fragment (PSI 757) of the third or fourth century has the first 6 verses of chapter 9, and there are a few fragments in Syriac of chapters 1, 19,20. The writings of Clement of Alexandria give a few brief quotations, as to a smaller extent do Origen, Didymus the Blind and Jerome.[2][3][4][5]

Status for Christians[]

The Epistle was attributed to Barnabas, the companion of Paul the Apostle, by Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215) and Origen (c. 184 – c. 253).[6] Clement quotes it with phrases such as "the Apostle Barnabas says".[7] Origen speaks of it as the General Epistle of Barnabas.[8] Its inclusion in close proximity to the New Testament in the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Hierosolymitanus witnesses to the near-canonical authority it held for some Christians,[6] but is evidence of its popularity and usefulness, not necessarily of canonicity.[9][10]

Eusebius (260/265 – 339/340), excluded it from "the accepted books", classifying it as among the "rejected" or "spurious" (νόθοι) writings, while also applying to it, as to many others, the term "the disputed books", but not the description "the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many", a class composed of the Epistle of James, the Second Epistle of Peter, and the Second and the Third Epistle of John. As for the Book of Revelation, Eusebius says it was rejected by some but by others placed among the accepted books.[11]

In the sixth-century Codex Claromontanus a list, dating from the third or fourth century, of Old Testament and New Testament books mentions, with an indication of doubtful or disputed canonicity, the Epistle of Barnabas along with the Pastor of Hermas, the Acts of Paul and the Apocalypse of Peter.[12][13]

The Stichometry of Nicephorus, a later list of uncertain date appended to the Chronography of the early 9th century Nikephoros I of Constantinople, puts the Epistle of Barnabas among its four "disputed" New Testament works — along with the Book of Revelation, the Revelation of Peter and the Gospel of the Hebrews — but not among its seven "New Testament apocrypha".[14][15]

Date of composition[]

In 16.3–4, the Epistle of Barnabas reads:

Furthermore he says again, "Behold, those who tore down this temple will themselves build it." It is happening. For because of their fighting it was torn down by the enemies. And now the very servants of the enemies will themselves rebuild it.

As commonly interpreted, this passage places the Epistle after the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70. It also places the Epistle before the Bar Kochba Revolt of AD 132, after which there could have been no hope that the Romans would help to rebuild the temple. The document must therefore come from the period between the two Jewish revolts. Attempts at identifying a more precise date are conjectures.[6][16] The Encyclopædia Britannica puts the latest possible date at AD 130. [17] and for the actual date of composition gives "circa AD 100".[18] Its 1911 edition opted strongly for "the reign of Vespasian (AD 70-79)", [19] shortly after the Catholic Encyclopedia had preferred AD 130−131 in an article by Paulin Ladeuze,[20] and AD 96−98 in an article by John Bertram Peterson.[21] On a more precise dating within the limits associated with the Jerusalem temple there is thus an "absence of scholarly consensus".[22][23][24]

Jay Curry Treat comments on the absence in the Epistle of Barnabas (except for a possible reference to the phrase "Many are called, but few are chosen" in the Gospel according to Matthew) of citations from the New Testament:

Although Barnabas 4:14 appears to quote Matt 22:14, it must remain an open question whether the Barnabas circle knew written gospels. Based on Koester's analysis (1957: 125–27, 157), it appears more likely that Barnabas stood in the living oral tradition used by the written gospels. For example, the reference to gall and vinegar in Barnabas 7:3, 5 seems to preserve an early stage of tradition that influenced the formation of the passion narratives in the Gospel of Peter and the synoptic gospels.[25]

Helmut Koester considers the Epistle to be earlier than the Gospel of Matthew: in his Introduction to the New Testament he says of the author of the Epistle: "It cannot be shown that he knew and used the Gospels of the New Testament. On the contrary, what Barnabas presents here is from 'the school of the evangelists'. This demonstrates how the early Christian communities paid special attention to the exploration of Scripture in order to understand and tell the suffering of Jesus. Barnabas still represents the initial stages of the process that is continued in the Gospel of Peter, later in Matthew, and is completed in Justin Martyr."[26]

An opposing view is enunciated by Everett Ferguson: "The language of rebuilding the temple in 16.3–5 refers to the spiritual temple of the heart of Gentile believers (any allusion to a physical temple in Jerusalem is doubtful)." On the date of composition he says: "The Epistle of Barnabas is usually dated to 130−135, although an earlier date in the late 70s has had its champions, and 96−98 is a possibility."[27]

Provenance[]

The place of origin is generally taken to be Alexandria in Egypt. It is first attested there (by Clement of Alexandria). Its allegorical style points to Alexandria. Barnabas 9:6 mentions idol-worshipping priests as circumcised, a practice in use in Egypt. However, some scholars have suggested an origin in Syria or Asia Minor.[27][28][29]

Treat comments on the provenance of the Epistle of Barnabas:[30]

Barnabas does not give enough indications to permit confident identification of either the teacher's location or the location to which he writes. His thought, hermeneutical methods, and style have many parallels throughout the known Jewish and Christian worlds. Most scholars have located the work's origin in the area of Alexandria, on the grounds that it has many affinities with Alexandrian Jewish and Christian thought and because its first witnesses are Alexandrian. Recently, Prigent (Prigent and Kraft 1971: 20–24), Wengst (1971: 114–18), and Scorza Barcellona (1975: 62–65) have suggested other origins based on affinities in Palestine, Syria, and Asia Minor. The place of origin must remain an open question, although the Gk-speaking E. Mediterranean appears most probable.

Contents[]

The Epistle of Barnabas has the form not so much of a letter (it lacks indication of identity of sender and addressees) as of a treatise. In this, it is like the Epistle to the Hebrews, which Tertullian ascribed to the apostle Barnabas[31] and with which it has "a large amount of superficial resemblance".[32] On the other hand, it does have some features of an epistolary character,[33] and Reidar Hvalvik argues that it is in fact a letter.[34]

The document can be divided into two parts. Chapters 1−17 give a Christ-centred interpretation of the Old Testament, which it says should be understood spiritually, not in line with the literal meaning of its rules on sacrifice (chapter 2: the sacrifice God wants is that of a contrite heart), fasting (3: the fasting God wants is from injustice), circumcision (9), diet (10: rules that really prohibit behaviour such as praying to God only when in need, like swine crying out when hungry but ignoring their master when full, or being predatory like eagle, falcon, kite and crow, etc.; and that command to chew by meditating the cud of the word of the Lord and to divide the hoof by looking for the holy world to come while walking in this world), sabbath (15), and the temple (16). The passion and death of Jesus at the hands of the Jews, it says, is foreshadowed in the properly understood rituals of the scapegoat (7) and the red heifer (8) and in the posture assumed by Moses in extending his arms (according to the Greek Septuagint text known to the author of the Epistle) in the form of the execution cross, while Joshua, whose name in Greek is Ἰησοῦς (Jesus), fought against Amalek (12). The last four chapters, 18−21, are a version of The Two Ways teaching that appears also in chapters 1−5 of the Didache.[35][36][37][38]

As viewed by Andrew Louth, the author "is simply concerned to show that the Old Testament Scriptures are Christian Scriptures and that the spiritual meaning is their real meaning".[39] As viewed by Bart D. Ehrman, the Epistle of Barnabas is "more anti-Jewish than anything that did make it into the New Testament".[40]

Midrash and gematria[]

According to David Dawson, "the Jewish mind-set of Barnabas, evident in its choice of images and examples, is unmistakable". He says that the work's two-part structure, with a distinct second part beginning with chapter 18, and its exegetical method "provide the most striking evidence of its Jewish perspective. It is presented as a talmud or didachē ('teaching') divided into haggadah and halakhah. It uses Philonic allegorical techniques to interpret fragments of Septuagint passages, in the manner of the midrashim. Finally, it applies biblical texts to its own contemporary historical situation in a manner reminiscent of the pesher technique found at Qumran."[41]

The creative interpretation of Bible texts, that is most typically found in rabbinic literature and is known as midrash, appears also in the New Testament and other early Christian works, where it is utilized with the prior assumption that the whole of the Bible relates to Christ.[42]

James L. Bailey judges as correct the classification as midrash of the frequent use by the evangelists of texts from the Hebrew Bible,[43] and Daniel Boyarin applies this in particular to the Prologue (1:1−18) of the Gospel of John.[44] Other instances of New Testament allegorical interpretations of the Old Testament scriptures as foreshadowing Jesus are John 3:14, Galatians 4:21−31 and 1 Peter 3:18−22.[45] Other examples of midrash-like exegesis are found in the accounts of the temptation of Christ in Matthew and Luke,[46] and of circumstances surrounding the birth of Jesus.[42]

Midrashic presentation of a writer's own views on the basis of the sacred texts was subject to well-established rules but some scholars, due to their failure to recognize the meaning and use of midrash, have evaluated pejoratively the use of scripture by such as Matthew.[47]

Similar negative judgments have been expressed on the abundant use of midrash[45][48][49] in the Epistle of Barnabas. In 1867, Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, in their Ante-Nicene Christian Library, disparaged the Epistle for what it called "the absurd and trifling interpretations of Scripture which it suggests".[50]

The Epistle of Barnabas also employs another technique of ancient Jewish exegesis, that of gematria, the ascription of religious significance to the numerical value of letters. When applied to letters of the Greek alphabet, it is also called isopsephia. A well-known New Testament instance of its use is in the Book of Revelation, "Let the one who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is 666",[51] which is often interpreted as referring to the name "Nero Caesar" written in Hebrew characters.[52] The interpretation of Genesis 17:23–27 in Barnabas 9:7–8 is considered "a classic example" of allegorical or midrashic interpretation:[53][54] "In reading the story of Abraham circumcising his household, his eye fell on the figure 318 which appeared in the scroll as ΤΙΗ. Now ΙΗ was a familiar contraction of the sacred name of Jesus, and is so written in the Alexandrian papyri of the period; and the letter Τ looked like the cross."[55] The same gematria was adopted by Clement of Alexandria and by several other Church Fathers: William Barclay notes that, because the letter T is shaped exactly like the crux commissa and because the Greek letter T represented the number 300, "wherever the fathers came across the number 300 in the Old Testament they took it to be a mystical prefiguring of the cross of Christ".[56]

Philip Carrington says: "Barnabas can be artificial, irritating, and censorious; but it would not be fair to judge him by his less fortunate expositions. His interpretation of the unclean beasts and fishes was in line with the thought of his time, being found in the Letter of Aristeas, for instance. His numerology was also a fashionable mode of thought, though the modern scholar is often impatient with it."[55] Robert A. Kraft states that some of the materials used by the final editor "certainly antedate the year 70, and are in some sense 'timeless' traditions of Hellenistic Judaism (e.g., the food law allegories of ch. 10, the Two Ways). It is with such materials that much of the importance of the epistle for our understanding of early Christianity and its late-Jewish heritage rests."[57] The author's style was not a personal foible: in his time it was accepted procedure in general use, although no longer in favour today. Andrew Louth says: "Barnabas seems strange to modern ears: allegory is out of fashion and there is little else in the epistle. But the fashion that outlaws allegory is quite recent, and fashions change."[58]

Gnosis[]

In its first chapter, the Epistle states that its intention is that the "sons and daughters" to whom it is addressed should have, along with their faith, perfect knowledge.[59] The knowledge (in Greek, γνῶσις, gnosis) that the first part (chapters 1−17) aims to impart is "an essentially practical γνῶσις, somewhat mystical in character, which seeks to make known the deeper sense of scripture". The first part, of an exclusively exegetical character, provides a spiritual interpretation of scripture.[60][61][62]

The second part opens with a declaration (chapter 18:1) that it is turning to "another knowledge" (γνῶσις). This second gnosis is "the knowledge of the will of God, the art of enumerating and specifying his commandments, and applying them to various situations",[60] a halakhic, as opposed to an exegetical, gnosis.[63]

The gnosis of the Epistle of Barnabas by no means links it with Gnosticism. On the contrary, it shows "an implicit anti-Gnostic stance": "Barnabas's gnosis can be seen as a precursor of the gnosis of Clement of Alexandria, who distinguished the 'true' gnosis from the 'knowledge falsely so-called' espoused by heretics".[63]

Scriptural quotations[]

Contrary to the views of Helmut Koester and Jay Curry Treat, cited above in relation to the date of composition of the Epistle, the authors of The Comprehensive New Testament say the Epistle of Barnabas quotes from the New Testament gospels twice (4:14, 5:9).[64]

On the other hand, the Epistle abundantly cites the Old Testament in the Septuagint version, including therefore the deuterocanonical books. The Old Testament material appears as allusions and paraphrases as well as explicit quotations. However, the work in no way distinguishes its quotations from sacred scripture from its quotations from other works, some of which are now unknown. Thus it is not clear whether material in the Epistle that, though not an exact quotation, resembles 1 Enoch (4:3; 16:5) or 4 Esdras (12:1) attributes to the supposed sources exactly the same status as books now considered canonical. Besides, the Epistle sometimes presents as quotations what are rather free paraphrases, while at other times it gives identifiable phrases without any introductory phrase to indicate that it is quoting.[65]

Notes[]

- ^ Reproduction of Codex Sinaiticus with GO TO (Barnabas)

- ^ James Carleton Paget, "The Epistle of Barnabas" in Paul Foster (editor), The Writings of the Apostolic Fathers (Bloomsbury 2007), p. 73

- ^ James N. Rhodes, The Epistle of Barnabas and the Deuteronomic Tradition (Mohr Siebeck 2004), p. xii

- ^ Sailors, Timothy B. "Bryn Mawr Classical Review: Review of The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations". Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ William Wright: A catalogue of the Syriac manuscripts preserved in the Library of the University of Cambridge (Vol. II). Cambridge: University Press 1901, 611.

- ^ a b c Geoffrey W. Bromiley (editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (Eerdmans 1979), vol. 1, p. 206

- ^ Stromata, book 2, chapters 6, 7, 15, 18, 20

- ^ Contra Celsum, book 1, chapter 63

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger, Michael J. Kruger, The Heresy of Orthodoxy (Crossway 2010), p. 164

- ^ Edmon L. Gallagher, John D. Meade, The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis (Oxford University Press 2017), p. 107

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea — On The Canon of the New Testament

- ^ Catalogue inserted in Codex Claromontanus

- ^ Stichometric list in Codex Claromontanus (about A.D. 400)

- ^ The Stichometery of Nicephorus (9th century?)

- ^ Erwin Preuschen, Analecta (1893), pp. 157−158

- ^ "Epistle of Barnabas 16.1-5" in Judaism and Rome

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Types of Biblical Hermeneutics" in Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Paulin Ladeuze, "Epistle of Barnabas" in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907)

- ^ John Bertram Peterson, "The Apostolic Fathers" in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907)

- ^ James N. Rhodes, The Epistle of Barnabas and the Deuteronomic Tradition: Polemics, Paraenesis, and the Legacy of the Golden-calf Incident (Mohr Siebeck 2004), p. 12

- ^ David Edward Aune, The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric (Westminster John Knox Press 2003), p. 72

- ^ Johannes Quasten, Patrology (Christian Classics) vol. 1, p. 90

- ^ Jay Curry Treat in The Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992) v. 1, p. 614

- ^ Helmut Koester, Introduction to the New Testament (Walter de Gruyter 1995), vol. 2, p. 281; original: Helmut Köster, Einführung in das Neue Testament im Rahmen der Religionsgeschichte und Kulturgeschichte der hellenistischen und römischen Zeit (Walter de Gruyter 1980), p. 716

- ^ a b Everett Ferguson, Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (Routledge 2013), p. 168

- ^ Johannes Quasten, Patrology (Christian Classics) vol. 1, p. 89

- ^ Aune (2003), p. 72

- ^ Jay Curry Treat in The Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992) v. 1, p. 613

- ^ F.F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Hebrews (Eerdmans 1990), p. 16

- ^ H.H.B. Ayles, Destination, Date, and Authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews (Cambridge University Press 1899), p. 150

- ^ James Carleton Paget, The Epistle of Barnabas: Outlook and Background (Mohr Siebeck 1994), p. 45

- ^ Reidar Hvalvik, The Struggle for Scripture and Covenant: The Purpose of the Epistle of Barnabas and Jewish-Christian Competition in the Second Century (Mohr Siebeck 1996), pp. 71−75

- ^ James N. Rhodes, The Epistle of Barnabas and the Deuteronomic Tradition: Polemics, Paraenesis, and the Legacy of the Golden-calf Incident (Mohr Siebeck 2004), p. 89

- ^ Johannes Quasten, Patrology (Christian Classics) vol. 1, pp. 85−86

- ^ James N. Rhodes, "Barnabas, Epistle of" in New Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: the battles for scripture and the faiths we never knew. Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- ^ Maxwell Staniforth, Andrew Louth, Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers (Penguin UK 1987), "real meaning"

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2016). Jesus, the Law, and a "New" Covenant (YouTube video). University of Michigan. Event occurs at 31:50~31:55. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ David Dawson, Allegorical Readers and Cultural Revision in Ancient Alexandria (University of California Press 1991), p. 175

- ^ a b Miguel Pérez Fernández, "Midrash and the New Testament" in Reimund Bieringer (editor), "The New Testament and Rabbinic Literature" (BRILL 2010), p. 367

- ^ James L. Bailey, Literary Forms in the New Testament: A Handbook (Westminster John Knox Press 1992), p. 157

- ^ Daniel Boyarin, "Logos, A Jewish Word: John's Prologue as Midrash" in Amy-Jill Levine, Marc Zvi Brettler (editor) The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford University Press 2017), pp. 688–691

- ^ a b "The Epistle of Barnabas: An Early Example of Allegorical Interpretation of the Old Testament" (Northern Kentucky University)

- ^ Birger Gerhardsson, The Testing of God's Son: (Matt. 4:1-11 & PAR), An Analysis of an Early Christian Midrash (Wipf and Stock 2009), p. 11

- ^ George Wesley Buchanan, The Gospel of Matthew (Wipf and Stock 2006), p. 26

- ^ Tim Hegedus, "Midrash and the Letter of Barnabas" in Biblical Theology Bulletin: Journal of Bible and Culture, volume 38, issue 1 (2007), pp. 20-26

- ^ Robert A. Kraft, The Epistle of Barnabas: Its quotations and their sources (Harvard University 1961)

- ^ "The Epistle of Barnabas" in Ante-Nicene Christian Library, vol. I (T&T Clark, Edinburgh 1867)

- ^ Rev 13:18

- ^ Larry W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Eerdmans 2006)

- ^ Roy B. Zuck, Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth (David C. Cook 2002), p. 33

- ^ William W. Klein, Craig L. Blomberg, Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. (editors), Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (Zondervan 2017)

- ^ a b Philip Carrington, The Early Christian Church: Volume 1, The First Christian Church (Cambridge University Press 2011), p. 491

- ^ William Barclay, The Apostles' Creed (Westminster John Knox Press, 1998), p. 79

- ^ Robert A. Kraft, The Apostolic Fathers, vol. 3: Barnabas and the Didache

- ^ Maxwell Staniforth, Andrew Louth, Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers (Penguin UK 1987)

- ^ Chapter 1:5

- ^ a b James Carleton Paget, The Epistle of Barnabas: Outlook and Background (Mohr Siebeck 1994), pp. 46−47

- ^ Richard Patrick Crosland Hanson, Allegory and Event: A Study of the Sources and Significance of Origen's Interpretation of Scripture (Westminster John Knox Press 2002), p. 97

- ^ Maxwell Staniforth, Andrew Louth, Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers (Penguin UK 1987), "gnosis"

- ^ a b Birger A. Pearson, "Earliest Christianity in Egypt" in James E. Goehring, Janet A. Timbie (editors), The World of Early Egyptian Christianity (CUA Press 2007), p. 102

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament", Cornerstone Publications (2008), ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ Reidar Hvalvik, The Struggle for Scripture and Covenant: The Purpose of the Epistle of Barnabas and Jewish-Christian Competition in the Second Century (Mohr Siebeck 1996), p. 333

External links[]

Works related to Epistle of Barnabas at Wikisource

Works related to Epistle of Barnabas at Wikisource- Greek text of Epistle of Barnabas

- Early Christian Writings: Epistle of Barnabas; e-texts of translations and introductions

- Biblicalaudio Letter of Barnabas 2012 Translation & Audio Version

- The Epistle of Barnabas: Its Quotations and Their Sources Robert A. Kraft

- Apostolic Fathers

- Apocryphal epistles

- 1st-century Christian texts

- 2nd-century Christian texts

- Texts in Koine Greek

- Antilegomena