Apocalypse of Paul

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

|

|

Related literature |

|

See also

|

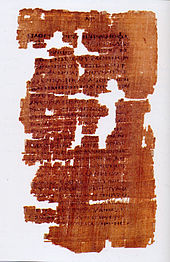

The Apocalypse of Paul (Apocalypsis Pauli, more commonly known in the Latin tradition as the Visio Pauli or Visio sancti Pauli) is a fourth-century non-canonical apocalypse considered part of the New Testament apocrypha.[1] The original Greek version of the Apocalypse is lost, although heavily redacted versions still exist. Using later versions and translations, the text has been reconstructed.[2] The text is not to be confused with the gnostic Coptic Apocalypse of Paul, which is unlikely to be related.

The text, which is pseudepigraphal, purports to present a detailed account of a vision of Heaven and Hell experienced by Paul the Apostle; "its chief importance lies in the way it helped to shape the beliefs of ordinary Christians concerning the afterlife".[3]

Authorship[]

Kirsti Copeland argues that the Apocalypse of Paul was composed at a communal Pachomian monastery in Egypt between 388-400 CE.[4] Bart Ehrman dates it to the 4th century.[5][6]

Content[]

The text is primarily focused on a detailed account of Heaven and Hell. It appears to be an elaborate expansion and rearrangement of the Apocalypse of Peter, although it differs in some ways. It contains a prologue describing all of creation appealing to God against the sin of man, which is not present in the Apocalypse of Peter. At the end of the text, Paul or the Virgin Mary (depending on the manuscript) manages to persuade God to give everyone in Hell a day off every Sunday.

The text expands upon the Apocalypse of Peter by framing the reasons for the visits to heaven and hell as the witnessing of the death and judgement of one wicked man and one righteous man. The text is heavily moralistic, and adds, to the Apocalypse of Peter, features such as:

- Pride is the root of all evil

- Heaven is the land of milk and honey

- Hell has rivers of fire and of ice (for the cold hearted)

- Some angels are evil, the dark angels of hell, including Temeluchus, the tartaruchi.

The plan of the text is:

- 1, 2. Discovery of the revelation.

- 3–6. Appeal of creation to God against man

- 7–10. The report of the angels to God about men.

- 11–18. Deaths and judgements of the righteous and the wicked.

- 19–30. First vision of Paradise, including lake Acherusa.

- 31–44. Hell. Paul obtains rest on Sunday for the lost.

- 45–51. Second vision of Paradise.

Versions[]

Greek copies of the texts are rare; those that exist contain many omissions. Of the Eastern versions – Syriac, Coptic, Amharic, Georgian – the Syriac are considered to be the most reliable. There is an Ethiopic version of the apocalypse which features the Virgin Mary in the place of Paul the Apostle, as the receiver of the vision, known as the Apocalypse of the Virgin.

The lost Greek original was translated into Latin as the Visio Pauli, and was widely copied, with extensive variation coming into the tradition as the text was adapted to suit different historical and cultural contexts; by the eleventh century, there were perhaps three main independent editions of the text. From these diverse Latin texts, many subsequent vernacular versions were translated, into most European languages, prominently including German and Czech.[7]

The Visio Pauli also influenced a range of other texts again. It is particularly noted for its influence in the Dante's Inferno (ii. 28[8]), when Dante mentions the visit of the ""[9] to Hell.[10] The Visio is also considered to have influenced the description of Grendel's home in the Old English poem Beowulf (whether directly or indirectly, possibly via the Old English Blickling Homily XVI).[11]

Further reading[]

- Jan N. Bremmer and Istvan Czachesz (edd). The Visio Pauli and the Gnostic Apocalypse of Paul (Leuven, Peeters, 2007) (Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha, 9).

- Eileen Gardiner, Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante (New York: Italica Press, 1989), pp. 13–46, provides an English translation of the Latin text.

- Lenka Jiroušková, Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter unter Einschluß der alttschechischen und deutschsprachigen Textzeugen (Leiden, Brill, 2006) (Mittellateinische Studien und Texte, 34).

- Theodore Silverstein and Anthony Hilhorst (ed.), Apocalypse of Paul (Geneva, P. Cramer, 1997).

- J. van Ruiten, "The Four Rivers of Eden in the Apocalypse of Paul (Visio Pauli): The Intertextual Relationship of Genesis 2:10–14 and the Apocalypse of Paul 23:4," in García Martínez, Florentino, and Gerard P. Luttikhuizen (edd), Jerusalem, Alexandria, Rome: Studies in Ancient Cultural Interaction in Honour of A. Hilhorst (Leiden, Brill, 2003).

- Nikolaos H. Trunte, Reiseführer durch das Jenseits: die Apokalypse des Paulus in der Slavia Orthodoxa (München – Berlin – Washington, D. C.: Verlag Otto Sagner. 2013) (Slavistische Beiträge 490).

References[]

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2003), Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, Oxford Press, pp. xiv, ISBN 9780195141832

- ^ Harry O. Maier, review of: Lenka Jiroušková, Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter, unter Einschluf/ der alttschechischen und deutschsprachi gen Textzeugen, Mittellateinische Studien und Texte, 34 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006), Speculum, 82 (2004), 1000-2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20466112.

- ^ Harry O. Maier, review of: Lenka Jiroušková, Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter, unter Einschluf/ der alttschechischen und deutschsprachi gen Textzeugen, Mittellateinische Studien und Texte, 34 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006), Speculum, 82 (2004), 1000-2 (p. 1000), https://www.jstor.org/stable/20466112.

- ^ Copeland, Kirsti (2006), The Wise, the Simple, the Pachomian Koinonia and the Apocalypse of Paul (PDF), retrieved 6 August 2020

- ^ Ehrman 2005, p. xiv.

- ^ Ehrman, D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- ^ Harry O. Maier, review of: Lenka Jiroušková, Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter, unter Einschluf/ der alttschechischen und deutschsprachi gen Textzeugen, Mittellateinische Studien und Texte, 34 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006), Speculum, 82 (2004), 1000-2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20466112.

- ^ Several versions and commentaries on Inferno, Canto II, 28 of the Divine Comedy. thinks it is an allusion to 2 Corinthians 12.

- ^ Acts 9:15: But the Lord said unto him, Go thy way: for he is a chosen vessel unto me, to bear my name before the Gentiles, and kings, and the children of Israel:

- ^ Harry O. Maier, review of: Lenka Jiroušková, Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter, unter Einschluf/ der alttschechischen und deutschsprachi gen Textzeugen, Mittellateinische Studien und Texte, 34 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006), Speculum, 82 (2004), 1000-2 (p. 1000), https://www.jstor.org/stable/20466112.

- ^ Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript, rev. edn (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003), pp. 38-41.

External links[]

- M.R. James' translation and commentary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924.

- Bibliography on the Apocalypse of Paul.

- 3rd-century Christian texts

- Ancient Greek books

- Apocryphal revelations

- Christian apocalyptic writings

- Texts in Koine Greek