First Epistle of Clement

| New Testament apocrypha |

|---|

|

| Apostolic Fathers |

|

1 Clement · 2 Clement Epistles of Ignatius Polycarp to the Philippians Martyrdom of Polycarp · Didache Barnabas · Diognetus The Shepherd of Hermas |

| Jewish–Christian gospels |

| Ebionites · Hebrews · Nazarenes |

| Infancy gospels |

| James · Thomas · Syriac · Pseudo-Matthew · History of Joseph the Carpenter |

| Gnostic gospels |

| Judas · Mary · Philip · Truth · Secret Mark · The Saviour |

| Other gospels |

| Thomas · Marcion · Nicodemus · Peter · Barnabas |

| Apocalypse |

|

Paul Peter Pseudo-Methodius · Thomas · Stephen 1 James · 2 James 2 John |

| Epistles |

|

Apocryphon of James Apocryphon of John Epistula Apostolorum Pseudo-Titus Peter to Philip Paul and Seneca |

| Acts |

|

Andrew · Barnabas · John · Mar Mari · The Martyrs Paul Peter · Peter and Andrew Peter and Paul · Peter and the Twelve · Philip Pilate · Thaddeus · Thomas · Timothy Xanthippe, Polyxena, and Rebecca |

| Misc. |

|

Diatessaron Doctrine of Addai Questions of Bartholomew Resurrection of Jesus Christ Prayer of the Apostle Paul |

| "Lost" books |

| Bartholomew · Matthias · Cerinthus · Basilides · Mani · Hebrews · Laodiceans |

| Nag Hammadi library |

The First Epistle of Clement (Ancient Greek: Κλήμεντος πρὸς Κορινθίους, romanized: Klēmentos pros Korinthious, lit. 'Clement to Corinthians') is a letter addressed to the Christians in the city of Corinth. Based on internal evidence some scholars say the letter was composed some time before AD 70,[1][2][3][4][need quotation to verify] but the common time given for the epistle's composition is at the end of the reign of Domitian (c. AD 96)[5][6] and AD 140, most likely around 96.[need quotation to verify] It ranks with Didache as one of the earliest, if not the earliest, of extant Christian documents outside the traditional New Testament canon. As the name suggests, a Second Epistle of Clement is known, but this is a later work by a different author. Part of the Apostolic Fathers collection, 1 and 2 Clement are not usually considered to be part of the canonical New Testament.

The letter is a response to events in Corinth, where the congregation had deposed certain elders (presbyters). The author called on the congregation to repent, to restore the elders to their position, and to obey their superiors. He said that the Apostles had appointed the church leadership and directed them on how to perpetuate the ministry.

The work is attributed to Clement I, the Bishop of Rome. In Corinth, the letter was read aloud from time to time. This practice spread to other churches, and Christians translated the Greek work into Latin, Syriac, and other languages. Some early Christians even treated the work like scripture. The work was lost for centuries, but since the 1600s various copies or fragments have been found and studied. It has provided valuable evidence about the structure of the early church.

Authorship and date[]

Although traditionally attributed to Clement of Rome,[7] the letter does not include Clement's name, and is anonymous, though scholars generally consider it to be genuine.[5] The epistle is addressed as "the Church of God which sojourneth in Rome to the Church of God which sojourneth in Corinth". Its stylistic coherence suggests a single author.[8]

Scholars have proposed a range of dates, but most limit the possibilities to the last three decades of the 1st century,[9][10] and no later than AD 140.[11] 1 Clement is dated by some scholars to some time before AD 70.[1][2][3] The common time given for the epistle's composition is at the end of the reign of Domitian (c. AD 96).[5][6] The phrase "sudden and repeated misfortunes and hindrances which have befallen us" (1:1) is taken as a reference to persecutions under Domitian. Some scholars believe that 1 Clement was written around the same time as the Book of Revelation (c. AD 95–97).[12]

Content[]

The letter was occasioned by a dispute in Corinth, which had led to the removal from office of several presbyters. Since none of the presbyters were charged with moral offences, 1 Clement charges that their removal was high-handed and unjustifiable. The letter is extremely lengthy—twice as long as the Epistle to the Hebrews—and includes many references to the Old Testament.[13]

1 Clement offers valuable evidence about the state of the ministry in the early church. He calls on the Corinthians to repent and to reinstate the leaders that they had deposed. He explains that the Apostles had appointed ”bishops and deacons”, that they had given instructions on how to perpetuate the ministry, and that Christians were to obey their superiors. The author uses the terms ”bishops” (overseers, episkopos) and ”elders” (presbyters) interchangeably.[5]

New Testament references include admonition to “Take up the epistle of the blessed Paul the Apostle” (xlvii. 1) which was written to this Corinthian audience; a reference which seems to imply written documents available at both Rome and Corinth. 1 Clement also alludes to the first epistle of Paul to the Corinthians; and alludes to Paul's epistles to the Romans, Galatians, Ephesians, and Philippians, Titus, 1 Timothy, numerous phrases from the Epistle to the Hebrews, and possible material from Acts. In several instances, the author asks his readers to “remember” the words of Jesus, although they do not attribute these sayings to a specific written account. These New Testament allusions are employed as authoritative sources which strengthen the letter's arguments to the Corinthian church. According to Bruce Metzger, Clement never explicitly refers to these New Testament references as “Scripture”.[13]

Additionally, 1 Clement expressly references the martyrdom of Paul and very strongly implies the martyrdom of Peter (sections 5:4 to 6:1).[14]

Thomas J. Herron states that 1 Clement 41:2's statement of "Not in every place, brethren, are sacrifices offered continually, either in answer to prayer, or concerning sin and neglect, but in Jerusalem only; and even there the offering is not made in every place, but before the temple in the court of the altar, after that which is offered has been diligently examined by the high priest and the appointed ministers" would only make sense if the work was composed before the temple was destroyed in 70 CE.[1]

1 Clement was written at a time when some Christians were keenly aware that Jesus had not returned as they had expected. Like the Second Epistle of Peter, this epistle criticizes those who had doubts about the faith because the Second Coming had not yet occurred.[15]

Canonical rank[]

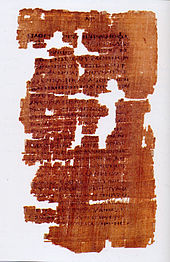

The epistle was publicly read from time to time in Corinth, and by the 4th century this usage had spread to other churches. It was included in the 5th century Codex Alexandrinus, which contained the entire Old and New Testaments.[16] It was included with the Gospel of John in the fragmentary early Greek and Akhmimic Coptic papyrus designated Papyrus 6. First Clement is listed as canonical in "Canon 85" of the Canons of the Apostles, showing that First Clement had canonical rank in at least some regions of early Christendom. Ibn Khaldun also mentions it as part of the New Testament,[17] suggesting that the book may have been in wide and accepted use in either 14th century Spain or Egypt.[citation needed]

Sources[]

Though known from antiquity, the first document to contain the Epistle of Clement and to be studied by Western scholars was found in 1628, having been included with an ancient Greek Bible given by the Patriarch of Constantinople Cyril I to King Charles I of England.[18] The first complete copy of 1 Clement was rediscovered in 1873, some four hundred years after the Fall of Constantinople, when Philotheos Bryennios found it in the Greek Codex Hierosolymitanus, written in 1056. This work, written in Greek, was translated into at least three languages in ancient times: a Latin translation from the 2nd or 3rd century was found in an 11th-century manuscript in the seminary library of Namur, Belgium, and published by Germain Morin in 1894; a Syriac manuscript, now at Cambridge University, was found by Robert Lubbock Bensly in 1876, and translated by him into English in 1899; and a Coptic translation has survived in two papyrus copies, one published by C. Schmidt in 1908 and the other by F. Rösch in 1910.[19][20]

The Namur Latin translation reveals its early date in several ways. Its early date is attested to by not being combined with the pseudepigraphic later Second Epistle of Clement, as all the other translations are found, and by showing no knowledge of the church terminology that became current later—for example, translating Greek presbyteroi as seniores rather than transliterating to presbyteri.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Herron, Thomas J. (2008). Clement and the Early Church of Rome: On the Dating of Clement's First Epistle to the Corinthians. Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thiede, Carsten Peter (1996). Rekindling the Word: In Search of Gospel Truth. Gracewing publishing. p. 71. ISBN 1-56338-136-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carrier, Richard (2014). On the Historicity of Jesus Sheffield. Phoenix Press. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-1-909697-49-2.

- ^ Licona, Michael (2010). The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach. Apollos. ISBN 184474485X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Clement of Rome, St." Cross, F. L. (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris p. 363

- ^ Jurgens, W A, ed. (1970), The Faith of the Early Fathers: A Source-book of Theological and Historical Passages from the Christian Writings of the Pre-Nicene and Nicene Eras, Liturgical Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-8146-0432-8, retrieved 18 April 2013

- ^ Holmes, Michael (1 November 2007), Apostolic Fathers, The: Greek Texts and English Translations, Baker Academic, p. 34, ISBN 978-0-8010-3468-8, retrieved 18 April 2013

- ^ Holmes, Michael (1 November 2007), Apostolic Fathers, The: Greek Texts and English Translations, Baker Academic, p. 35, ISBN 978-0-8010-3468-8, retrieved 18 April 2013

- ^ Herron, Thomas (2008). Clement and the Early Church of Rome: On the Dating of Clement's First Epistle to the Corinthians. Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road. p. 47.

In the context of 1 Clement’s strategy to win over the Corinthians to a renewed sense of order in their community, any reference to a Temple which stood in ruins would simply make no sense . . . It is easier to believe that 1 Clement wrote while the Temple still stood, i.e. in circa A.D. 70.

- ^ L.L. Welborn, "The preface to 1 Clement: the rhetorical situation and the traditional date", in Breytenbach and Welborn, p. 201

- ^ W.C. van Unnik, "Studies on the so-called First Epistle of Clement. The literary genre," in Cilliers Breytenbach and Laurence L. Welborn, Encounters with Hellenism: Studies on the First Letter of Clement, Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2004, p. 118. ISBN 9004125264.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bruce M. Metzger, Canon of the New Testament (Oxford University Press) 1987:42–43.

- ^ McDowell, Sean (2015). The Fate of the Apostles. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 55–114.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. p. 363

- ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 107, 109. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- ^ Ibn Khaldun (1958) [1377], "Chapter 3.31. Remarks on the words "Pope" and "Patriarch" in the Christian religion and on the word "Kohen" used by the Jews", Muqaddimah, translated by Rosenthal, Franz.

- ^ Staniforth, Maxwell (1975). Early Christian writings: the Apostolic Fathers. Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1968. p. 14. ISBN 0-14-044197-2.

- ^ A second manuscript containing a Syriac version of 1 Clement is mentioned in Sailors, Timothy B. "Bryn Mawr Classical Review: Review of The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations". Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ JB Lightfoot and JR Harmer, ed. (1891), The Apostolic Fathers: Revised Greek Texts with Introductions and English Translations, Baker Books, 1988 reprint, p. 4, retrieved 21 April 2016

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: First Epistle of Clement |

- Catholic Encyclopedia article on Clement of Rome

- Early Christian writings: The First Epistle of Clement – Useful links

- Lexundria: 1 Clement: Epistle of the Romans to the Corinthians – English translation by Kirsopp Lake

- Patristics: Clement: Epistle to the Corinthians – Patristics.co

- The Use of Material Deriving from the Synoptic Gospels in the Letter of Clement to the Corinthians

- 2012 Translation & Audio Version

The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Apocryphal epistles

- 2nd-century Christian texts

- 1st-century Christian texts

- Apostolic Fathers

- Documents of Pope Clement I