Gospel of Marcion

The Gospel of Marcion, called by its adherents the Gospel of the Lord, was a text used by the mid-2nd-century Christian teacher Marcion of Sinope to the exclusion of the other gospels. The majority of scholars agree the gospel was an edited version of the Gospel of Luke.

Although no manuscript of Marcion's gospel survives, scholars such as Adolf von Harnack and Dieter T. Roth[2] have been able to largely reconstruct the text from quotations in the anti-Marcionite treatises of orthodox Christian apologists such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Epiphanius.

Contents[]

Marcion's Gospel has been reconstructed from quotes taken from the works of others, with Tertullian contributing the most quotes and Epiphanius being the second most important source of text.[3]

Like the Gospel of Mark, Marcion's gospel lacked any nativity story. Luke's account of the baptism of Jesus was also absent. The gospel began, roughly, as follows:

In the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, Jesus descended into Capernaum, a city in Galilee, and was teaching on the Sabbath days.[4][5] (cf. Luke 3:1a, 4:31)

Other Lukan passages that did not appear in Marcion's gospel include the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son.[6]: 170

While Marcion preached that the God who had sent Jesus Christ was an entirely new, alien god, distinct from the vengeful God of Israel who had created the world,[7]: 2 this view was not explicitly taught in Marcion's gospel.[6]: 169 The Gospel of Marcion is, however, much more amenable to a Marcionite interpretation than the canonical Gospel of Luke, because it lacks many of the passages in Luke that explicitly link Jesus with Judaism, such as the parallel birth narratives of John the Baptist and Jesus in Luke 1-2.

Three hypotheses on the gospels of Marcion and Luke[]

There are three hypotheses concerning the relationship between the gospel of Marcion and the gospel of Luke:[8]

1. Marcion's Evangelion derives from Luke by a process of reduction (The Patristic Hypothesis).

2. Luke derives from Marcion's Evangelion by a process of expansion (The Schwegler Hypothesis).

3. Marcion's Evangelion and Luke are both independent developments of a common proto-gospel (The Semler Hypothesis).

As a revision of Luke (Patristic hypothesis)[]

Church Fathers wrote, and Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman agree, that Marcion edited Luke to fit his own theology, Marcionism.[9][10] The late 2nd-century writer Tertullian stated that Marcion, "expunged [from the Gospel of Luke] all the things that oppose his view... but retained those things that accord with his opinion".[11] This view, that the Gospel of Marcion was a revision of the Gospel of Luke, is the traditional view, and may be called the Patristic hypothesis.[12]

According to this view, Marcion eliminated the first two chapters of Luke concerning the nativity, and began his gospel at Capernaum making modifications to the remainder suitable to Marcionism. The differences in the texts below highlight the Marcionite view that Jesus did not follow the Prophets and that the earth is evil.

| Luke | Marcion |

|---|---|

| O foolish and slow of heart to believe in all that the prophets have spoken (24:25) | O foolish and hard of heart to believe in all that I have told you |

| They began to accuse him, saying, 'We found this man perverting our nation' (23:2) | They began to accuse him, saying, 'We found this man perverting our nation [...] and destroying the law and the prophets.' |

| I thank Thee, Father, Lord of heaven and earth (10:21) | I thank Thee, Heavenly Father... |

Late 19th- and early 20th-century theologian Adolf von Harnack, in agreement with the traditional account of Marcion as revisionist, theorized that Marcion believed there could be only one true gospel, all others being fabrications by pro-Jewish elements, determined to sustain worship of Yahweh; and that the true gospel was given directly to Paul the Apostle by Christ himself, but was later corrupted by those same elements who also corrupted the Pauline epistles. In this understanding, Marcion saw the attribution of this gospel to Luke the Evangelist as a fabrication, so he began what he saw as a restoration of the original gospel as given to Paul.[13] Von Harnack wrote that:

For this task he did not appeal to a divine revelation, any special instruction, nor to a pneumatic assistance [...] From this it immediately follows that for his purifications of the text - and this is usually overlooked - he neither could claim nor did claim absolute certainty.[13]

Semler hypothesis and Schwegler hypothesis[]

Numerous biblical scholars have rejected from the traditional view that the Gospel of Marcion was a revision of the Gospel of Luke (the Patristic hypothesis).[12] "[T]here has been a long line of scholars" who, against what the Church Fathers said, claimed "that our canonical Luke forms an enlarged version of a 'Proto-Luke' which was also used by Marcion. This dispute [...] was especially vivid in nineteenth century German scholarship". In 1942, John Knox published his Marcion and the New Testament, defending that the gospel of Marcion had the chronological priority over Luke. After this publication, no defense of this theory was made again until two 2006 articles: one of Joseph Tyson, and one of Matthias Klinghardt.[14]

Biblical scholars who reject the Patristic hypothesis defend either of the two hypotheses. One group argues that both gospels are independent redactions of a "proto-Luke", with Marcion's text being an unaltered version of this proto-Luke or closer to the original proto-Luke; this position is called the Semler hypothesis after the name of its creator, Johann Salomo Semler; this position is supported among others by Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, John Knox, Karl Reinhold Köstlin, Joseph B. Tyson, and Jason BeDuhn.[12][15] The other group argues that the Gospel of Luke is a later redaction of the Gospel of Marcion aiming at correcting the gospel of Marcion; this position is called the Schwegler hypothesis after its creator Albert Schwegler; this position is supported among others by Albrecht Ritschl, Paul-Louis Couchoud, John Townsend, Matthias Klinghardt,[12] Markus Vinzent,[16][17][18] and David Trobisch.[19]

Several arguments have been put forward in favor of those two latter views.

Firstly, there are many passages found in reconstructions of Marcion's gospel (based on comments of his detractors) that seem to contradict Marcion's own theology, which would be unexpected if Marcion was simply removing passages from Luke which he hadn't agreed with. Matthias Klinghardt has argued in 2008:

The main argument against the traditional view of Luke’s priority to [Marcion] relies on the lack of consequence of his redaction: Marcion presumably had theological reasons for the alterations in "his" gospel which implies that he pursued an editorial concept. This, however, cannot be detected. On the contrary, all the major ancient sources give an account of Marcion’s text, because they specifically intend to refute him on the ground of his own gospel. Therefore, Tertullian concludes his treatment of [Marcion]: "I am sorry for you, Marcion: your labour has been in vain. Even in your gospel Christ Jesus is mine" ([Tert. Adv. Marc.] 4.43.9).[20] (emphasis in original)

Secondly, Marcion is said to have claimed that the gospel he used was original and the canonical Luke was a falsification.[20]: 8 The accusations of alteration are therefore mutual:

Tertullian, Epiphanius, and other ancient witnesses, all of whom knew and accepted the same Gospel of Luke we know, felt not the slightest doubt that the "heretic" had shortened and "mutilated" the canonical Gospel; and on the other hand, there is every indication that the Marcionites denied this charge and accused the more conservative churches of having falsified and corrupted the true Gospel which they alone possessed in its purity. These claims are precisely what we would have expected from the two rival camps, and neither set of them deserves much consideration.[7]: 78

Thirdly, John Knox and have shown that, of the material that is omitted from Marcion's gospel but included in canonical Luke, the vast majority (79.5-87.2%) is unique to Luke, with no parallel in the earlier gospels of Mark and Matthew.[7]: 109 [21]: 87 They argue that this result is entirely expected if canonical Luke is the result of adding new material to Marcion's gospel or its source, but that it is very much unexpected if Marcion removed material from Luke.

"In the mid-twentieth century, John Knox introduced a variation on the Semler Hypothesis that combined it with elements of the other two hypotheses [the Patristic and Schwegler[a]]": he considers that the gospels of Luke and Marcion date back to a common source, and that the gospel of Marcion removed parts of this source, while that Luke added some parts not originally present in this source. This hypothesis was developed further by Joseph B. Tyson. Knox and Tyson also studied the Book of Acts, and "[b]oth find an anti-Marcionite intent behind the handling of Paul in Acts."[23]

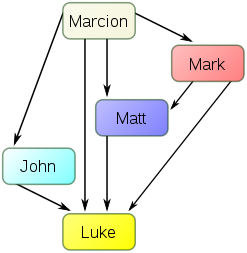

As a version of Mark[]

In 2008, Matthias Klinghardt proposed that Marcion's gospel was based on the Gospel of Mark, that the Gospel of Matthew was an expansion of the Gospel of Mark with reference to the Gospel of Marcion, and that the Gospel of Luke was an expansion of the Gospel of Marcion with reference to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. In Klinghardt's view, this model elegantly accounts for the double tradition— material shared by Matthew and Luke, but not Mark— without appealing to purely hypothetical documents, such as the Q source.[20]: 21–22, 26 In his 2015 book, Klinghardt changed his opinion compared to his 2008 article. In his 2015 book, he considers that the gospel of Marcion precedes and influenced the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John).[24]

Research from 2018 suggests that the Gospel of Marcion may have been the original two-source gospel based on Q and Mark.[25]

As the first gospel[]

In his 2014 book Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, Markus Vinzent considers, like Klinghardt, that the gospel of Marcion precedes the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). He believes that the Gospel of Marcion influenced the four gospels. Vinzent differs with both BeDuhn and Klinghardt in that he believes the Gospel of Marcion was written directly by Marcion: Marcion's gospel was first written as a draft not meant for publication which was plagiarized by the four canonical gospels; this plagiarism angered Marcion who saw the purpose of his text distorted and made him publish his gospel along with a preface (the Antithesis) and 10 letters of Paul.[16][26][18]

The Marcion priority also implies a model of the late dating of the New Testament Gospels to the 2nd century - a thesis that goes back to David Trobisch, who, in 1996 in his habilitation thesis accepted in Heidelberg,[27] presented the conception or thesis of an early, uniform final editing of the New Testament canon in the 2nd century.[28]

Notes[]

- ^ "In the opinion of John Knox, the evidence of different exposures of Luke and the Evangelion to harmonizing textual influence means that the derivation of either text directly from the other seems to be ruled out on strictly textcritical grounds—in other words, both the Patristic Hypothesis and the Schwegler Hypothesis are historically impossible"[22]

- ^ Translated as Klinghardt, Matthias (2021). The Oldest Gospel and the Formation of the Canonical Gospels. Biblical Tools and Studies, 41. Vol. 1 & 2. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-4310-0. OCLC 1238089165.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Clivaz, C., The Angel and the Sweat Like 'Drops of Blood' (Lk 22:43–44): P69 and f13, HTR 98 (2005), p. 420

- ^ Roth, Dieter T. (2015). The Text of Marcion's Gospel. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24520-4.

- ^ Roth, Dieter T. (2015-01-01). 6 Epiphanius as a Source. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-28237-7.

- ^ Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.7.1

- ^ Epiphanius, Panarion 42.11.4

- ^ a b BeDuhn, Jason. "The New Marcion" (PDF). Forum. 3 (Fall 2015): 163–179.

- ^ a b c Knox, John (1942). Marcion and the New Testament: An Essay in the Early History of the Canon. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 978-0404161835.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason (2013). "The Evangelion". The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2003). Lost Christianities. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 108.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce (1989) [1987]. "IV. Influences Bearing on the Development of the New Testament". The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origins, Developments and Significance (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 92–99.

- ^ Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.6.2

- ^ a b c d BeDuhn, Jason (2013). "The Evangelion". The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. pp. 78–79, 346–347. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ a b Adolf von Harnack: Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God (1924) translated by John E. Steely and Lyle D. Bierma

- ^ Moll, Sebastian (2010). The Arch-Heretic Marcion. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 90–102. doi:10.1628/978-3-16-151539-2.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason (2013). "The Evangelion". The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ a b Vinzent, Markus (2015). "Marcion's Gospel and the Beginnings of Early Christianity". Annali di Storia dell'esegesi. 32 (1): 55–87 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2015). "Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, written by Markus Vinzent". Vigiliae Christianae. 69 (4): 452–457. doi:10.1163/15700720-12301234. ISSN 1570-0720.

- ^ a b Vinzent, Markus (2016-11-24). "I am in the process of reading your book 'Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels' ..." Markus Vinzent's Blog. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Trobisch, David (2018). "The Gospel According to John in the Light of Marcion's Gospelbook". In Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias (eds.). Das Neue Testament und sein Text im 2.Jahrhundert. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter. Vol. 61. Tübingen, Germany: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag GmbH. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-3-7720-8640-3.

- ^ a b c Klinghardt, Matthias (2008). "The Marcionite Gospel and the Synoptic Problem: A New Suggestion". Novum Testamentum. 50 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1163/156853608X257527. JSTOR 25442581.

- ^ Tyson, Joseph (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570036507.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason (2013). "The Evangelion". The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason (2013). "The Evangelion". The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- ^ Klinghardt, Matthias (2015-03-25). "IV. Vom ältesten Evangelium zum kanonischen Vier-Evangelienbuch: Eine überlieferungsgeschichtliche Skizze". Das älteste Evangelium und die Entstehung der kanonischen Evangelien (in German). A. Francke Verlag. pp. 190–231. ISBN 978-3-7720-5549-2.

- ^ Bilby, M. G.; Kochenash, M.; Froelich, M., eds. (2018). First Dionysian Gospel: Imitational and Redactional Layers in Luke and John in Classical Greek Models of the Gospels and Acts: Studies in Mimesis Criticism (Claremont Studies in New Testament & Christian Origins). Claremont, CA: Claremont Press. pp. 49–68. ISBN 9781946230188.

- ^ BeDuhn, Jason David (2015-09-16). "Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, written by Markus Vinzent". Vigiliae Christianae. 69 (4): 452–457. doi:10.1163/15700720-12301234. ISSN 1570-0720.

- ^ David Trobisch: Die Endredaktion des Neuen Testamentes: eine Untersuchung zur Entstehung der christlichen Bibel. Universitäts-Verlag, Freiburg, Schweiz; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, zugl.: Heidelberg, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 1994, ISBN 3-525-53933-9 (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), ISBN 3-7278-1075-0 (Univ.-Verl.) (= Novum testamentum et orbis antiquus 31).

- ^ Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias, eds. (2018). Das Neue Testament und sein Text im 2.Jahrhundert. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter. Vol. 61. Tübingen, Germany: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag GmbH. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-7720-8640-3.

External links[]

- The Marcionite Research Library: contains a full text in English with hyperlinks to the reconstruction sources.

Further reading[]

- G.R.S. Mead, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten (London and Benares, 1900; 3rd edition 1931): pp. 241– 249 Introduction to Marcion

- Burkitt, F.C. (1911). "Ch. 9. Marcion: Christianity without History". The Gospel History & its Transmission. London.

- History of the Christian Religion to the Year Two-Hundred by Charles B. Waite: It includes a chapter where he compares Marcion and Luke

- Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle by Joseph B. Tyson A case in favor of the view that the canonical Luke-Acts duo is a response to Marcion. Tyson also recounts the history of scholarly studies on Marcion up to 2006.

- 2nd-century Christian texts

- Apocryphal Gospels

- Gnostic Gospels

- Gospel of Luke

- Marcionism