Epistula Apostolorum

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2016) |

The Epistula Apostolorum (Latin for Epistle of the Apostles) is a work from the New Testament apocrypha. Probably dating from the 2nd century CE, it was within the canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church[citation needed], but not rediscovered in the Western world until the early 20th century. In 51 chapters, it takes the form of a letter from the apostles describing key events of the life of Jesus, followed by a dialogue between Jesus and the apostles.

The work's apparent intent is to uphold orthodox Christian doctrine, refuting Gnosticism - in particular the teachings of Cerinthus - and docetism. Although presented as having been written shortly after the Resurrection, it refers to Paul of Tarsus. It offers predictions of the fall of Jerusalem and of the Second Coming.

Origin[]

The text is commonly dated to the 2nd century, perhaps towards the middle of it. [1] CE Hill (1999) dates the Epistle to "just before 120, or in the 140s" and places "... the Epistula in Asia Minor in the first half of the second century."[2]

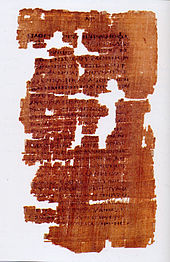

The text was used regularly by the relatively isolated Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and was evidently not considered heretical. The work was lost to the West until 1895 when major portions of it were discovered in the Coptic language and a complete version translated into Ethiopic was discovered and published in the early 20th century.[3] The fragmentary Coptic manuscript of the 5th or 4th century, is believed to be translated directly from the original Greek. One leaf of a Latin palimpsest, dating to the 5th century has also been identified as deriving from the same text.[4]

Format[]

The text is framed as a letter from the 11 apostles to the worldwide church, as a report from Jesus involving a dialogue between them and Jesus, which occurs between Jesus's resurrection and ascension.[5] The first 20% (10 chapters) begins by describing the nativity, resurrection, and miracles of Jesus, this framing is only done extremely superficially. The remainder of the text recounts a vision and dialogue between Jesus and the apostles, consisting of about sixty questions, and 41 short chapters. The text is by far the largest epistle in either the New Testament or Apocrypha.

Content[]

The text itself appears to be based on parts of the New Testament, in particular the Gospel of John, as well as the Apocalypse of Peter, Epistle of Barnabas, and Shepherd of Hermas, all of which were considered inspired by various groups or individuals during periods of the early church.

Countering Gnosticism[]

The whole text seems to have been intended as a refutation of the teachings of Cerinthus, although "Simon" (probably Simon Magus) is also mentioned.[6] The content heavily criticises Gnosticism, although it does so not so much as a polemic against it, as an attempt to shore up the faith of non-Gnostics against conversion to Gnosticism. In particular the text uses the style of a discourse and series of questions with a vision of Jesus that was popular among Gnostic groups,[7] so as to appeal to the same readers.

However, the text is at pains to point out that it is not a secret teaching, that the content applies universally rather than to one group, and that everyone can easily come to learn its content, strongly differing with the esoteric mysteries inherent in Gnosticism.

Parable of the foolish virgins[]

One of the most important parts in this respect is the parable of foolish virgins:

And we said to him: "Lord, who are the wise and who are the foolish?" He said to us: "Five are wise and five foolish; for these are those of whom the prophet has spoken: 'Sons of God are they.' Hear now their names."

But we wept and were troubled for those that slumbered. He said to us: "The five wise are Faith and Love and Grace and Peace and Hope. Now those of the faithful which possess this shall be guides to those that have believed in me and on he that sent me. For I am the Lord and I am the bridegroom whom they have received, and they have entered in to the house of the bridegroom and are laid down with me in the bridal chamber rejoicing. But the five foolish, when they had slept and had awaken, came to the door of the bridal chamber and knocked, for the doors were shut. Then they wept and lamented that no one opened to them."

We said unto him: "Lord, and their wise sisters that were within in the bridegroom's house, did they continue without opening to them, and did they not sorrow for their sakes nor entreat the bridegroom to open to them?" He answered us, saying: "They were not yet able to obtain favour for them." We said to him: "Lord, on what day shall they enter in for their sisters' sake?" Then said he to us: "He that is shut out, is shut out." And we said unto him: "Lord, is this word (determined?). Who then are the foolish?" He said to us: "Hear their names. They are Knowledge, Understanding (Perception), Obedience, Patience, and Compassion. These are they that slumbered in them that have believed and confessed me but have not fulfilled my commandments."

— Chapter 42-43

The Resurrection[]

Other polemical features include emphasising the physical nature of the resurrection, to counter docetism, by having the apostles place their fingers in the print of the nails, in the spear wound in his side, and checking for footprints (like similar imagery in the Gospel of John, having the appearance of design to specifically counter docetism rather than to reflect history).

Fully 20% of the text is devoted to confirming the doctrine of resurrection of the flesh, in direct conflict with the Gospel of Truth's criticism of this stance; the latter book states that the resurrection of the flesh happens before death, which is to be understood esoterically. When Jesus is questioned further on this point, he becomes quite angry, suggesting that the pseudonymous author of the epistle found the Gnostics' stance both offensive and infuriating.

Allusions to Paul[]

Since the text is ostensibly written in name of the apostles from the period immediately after Jesus' resurrection, it necessarily excludes Paul of Tarsus from the category "apostle". However, given the importance of Paul and his writings to the mainstream church, it is not surprising that the author of the text chose to put in a prediction of Paul's future coming. The description of the healing of Paul's blindness in Acts by Ananias is changed to healing by the hands of one of the apostles, so that Paul is thus subordinate to them.

Prophecies[]

The work quotes an ancient prophecy about a new Jerusalem arising from Syria and the old Jerusalem being captured and destroyed (as happened in 70). This latter prophecy is likely to have been invented, as it is unknown in any previous texts.

One of the reasons that the text probably fell into disuse by the mainstream churches is that its claim that the Second Coming shall be 150 years after the time of the vision to the apostles obviously failed to occur. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church apparently accepted the Epistle as basic orthodoxy. The work is described as canonical (under the name "the Letter of Judas the Zealot") in the (Gelasian Decree), (traditionally thought to be a Decretal of Pope Gelasius I(492-496) as of c. 366-383.[8][9]

Bibliography[]

- Epistula Apostolorum, introduction by C.D.G. Muller, p. 249ff, in New Testament Apocrypha: Gospels and related writings, Volume 1. Wilhelm Schneemelcher, ed., Westminster John Knox Press, 1991 ISBN 0-664-22721-X

- The Epistula Apostolorum: An Asian Tract from the Time of Polycarp, Hill, Charles E., 1999, Journal of Early Christian Studies, Volume 7:1, p. 1–53

- J. Hills, Tradition and Composition in the Epistula Apostolorum, Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990.

, , Turnhout, Brepols, coll. « Apocryphes n° 5 », 1994 ISBN 2-503-50400-0

Notes[]

- ^ (See New Testament Apocrypha: Gospels and related writings, Volume 1. Wilhelm Schneemelcher, ed., Westminster John Knox Press, 1991 ISBN 0-664-22721-X, p. 251).

- ^ CE Hill, 1999, The Epistula Apostolorum: An Asian Tract from the Time of Polycarp, p.1

- ^ Helmut Koester (1995). Introduction to the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 243–. ISBN 978-3-11-014970-8.

- ^ M.R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford, 1924) 485-503.

- ^ Allie M. Ernst (2009). Martha from the Margins: The Authority of Martha in Early Christian Tradition. BRILL. pp. 67–. ISBN 90-04-17490-7.

- ^ Antti Marjanen; Petri Luomanen (2008). A Companion to Second-Century Christian 'Heretics'. BRILL. pp. 213–. ISBN 90-04-17038-3.

- ^ Wilhelm Schneemelcher; Robert McLachlan Wilson (28 July 2005). New Testament Apocrypha. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 229–. ISBN 978-0-664-22721-0.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2020-10-23, retrieved 2020-12-08

- ^ "Tertullian : Decretum Gelasianum (English translation)". www.tertullian.org. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

External links[]

- Apocryphal epistles

- Christian anti-Gnosticism

- 2nd-century Christian texts