Devil in Christianity

In mainstream Christianity, the Devil, Satan or Lucifer is a fallen angel who rebelled against God in an attempt to become equal to God himself.[a] The devil was expelled from Heaven at the beginning of time, before God created the material world, and is in constant opposition to God.[2][3]

The Devil is often identified as the serpent in the Garden of Eden. He also has been identified as the accuser of Job, the tempter of the Gospels, Leviathan, and the dragon in the Book of Revelation.

The standard Medieval depiction of this event was set up by Gregory the Great. He integrated the devil, as the first creation of God, into the Christian angelic hierarchy as the highest of the angels (either a cherub or a seraph). But as high as he stood in heaven, so far he fell into the depths of hell and became the leader of demons.[4]

Old Testament[]

Satan in the Old Testament[]

The original Hebrew term śāṭān (Hebrew: שָּׂטָן) is a generic noun meaning "accuser" or "adversary",[5][6] which is used throughout the Hebrew Bible to refer to ordinary human adversaries,[7][6] as well as a specific supernatural entity.[7][6] The word is derived from a verb meaning primarily "to obstruct, oppose".[8] When it is used without the definite article (simply satan), the word can refer to any accuser,[7] but when it is used with the definite article (ha-satan), it usually refers specifically to the heavenly accuser: the satan.[7] Most Christians identify the satan with the devil.

The word with the definite article Ha-Satan occurs 17 times in the Masoretic Text, in two books of the Hebrew Bible: Job ch. 1–2 (14×) and Zechariah 3:1–2 (3×).[9] [10] It is translated in English bibles mostly as 'Satan' (18x in Book of Job, I Books of Chronicles and Book of Zechariah).

The word without the definite article is used in 10 instances, of which two are translated diabolos in the Septuagint. It is translated in English Bibles as 'an accuser' (1x) but mostly as 'an adversary' (9x as in Book of Numbers, 1 & 2 Samuel and 1 Kings).

Job's adversary[]

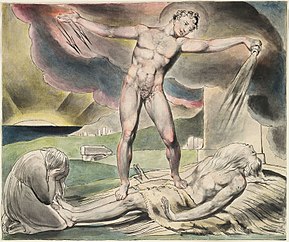

In the Book of Job, Job is a righteous man favored by God.[11] Job 1:6–8 describes the "sons of God" (bənê hāʼĕlōhîm) presenting themselves before God.[11] God asks one of them, Satan, where he has been, to which he replies that he has been roaming around the earth.[11] God asks, "Have you considered My servant Job?"[11] Satan replies by urging God to let him torture Job, promising that Job will abandon his faith at the first tribulation.[12] God consents; Satan destroys Job's servants and flocks, yet Job refuses to condemn God.[12]

This is one of two Old Testament passages, along with Zechariah 3, where Hebrew ha-Satan (the Adversary) becomes Greek ho diabolos (the Slanderer) in the Greek Septuagint used by the early Christian church. Originally, only the epithet of "the satan" ("the adversary") was used to denote the character in the Hebrew deity's court that later became known as "the Devil".[13]

Maximus the Confessor argued that the purpose of the devil is to teach humans how to distinguish between virtue and sin. Since, according to Christian teachings, the devil was cast out of the heavenly presence (unlike the Jewish Satan, who still functions as an accuser angel at service of God), Maximus explained how the devil could still talk to God, as told in the Book of Job, despite being banished. He argues that, as God is omnipresent within the cosmos, Satan was in God's presence when he uttered his accusation towards Job without being in the heavens. Only after the Day of Judgement, when the rest of the cosmos reunites with God, the devil, his demons, and all whose who cling to evil and unreality will exclude themselves eternally from God and suffer from this separation.[14]

David and Satan[]

A satan is involved in David's census and Christian teachings about this satan varies, just as the pre-exilic account of 2 Samuel and the later account of 1 Chronicles present differing perspectives:

- 2 Samuel 24:1 And the anger of the LORD was again kindled against Israel, and stirred up David against them, saying: Go, number Israel and Judah.

- 1 Chronicles 21:1 However, Satan rose up against Israel, and moved David to number Israel.

According to some teachings, this term refers to a human being, who bears the title satan while others argue that it indeed refers to a heavenly supernatural agent, an angel. Since the satan is sent by the will of God, his function resembles less the devilish enemy of God, and even if it is accepted that this satan refers to a supernatural agent, it is not necessarily implied this is the Satan. However, since the role of the figure is identical to that of the devil, viz. leading David into sin, most commentators and translators agree that David's satan is to be identified with Satan and the Devil.[15]

Book of Zechariah[]

Zechariah's vision of recently deceased Joshua the High Priest depicts a dispute in the heavenly throne room between Satan and the Angel of the Lord (Zechariah 3:1–2). The scene describes Joshua the High Priest dressed in filthy rags, representing the nation of Judah and its sins,[16] on trial with God as the judge and Satan standing as the prosecutor.[16] Yahweh rebukes Satan[16] and orders that Joshua be given clean clothes, representing God's forgiveness of Judah's sins.[16] Goulder (1998) views the vision as related to opposition from Sanballat the Horonite.[17] Again, Satan acts in accordance with God's will. The text implies he functions both as God's accuser and executioner.[18]

Identified with the Devil[]

Some parts of the Bible, which do not originally refer to an evil spirit or Satan, have been retrospectively interpreted as references to the devil.[19]

The serpent[]

Genesis 3 mentions the serpent in the Garden of Eden, which tempts Adam and Eve into eating the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil from the forbidden tree, thus causing their expulsion from the Garden. God rebukes the serpent, stating: "I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel."[20] Although the Book of Genesis never mentions Satan,[21] Christians have traditionally interpreted the serpent in the Garden of Eden as the devil due to Revelation 12:7, which describes the devil as "that ancient serpent called the Devil, or Satan, the one deceiving the whole world; was thrown down to the earth with all his angels.".[22][6] This chapter is used not only to explain the fall of mankind but also to remind the reader of the enmity between Satan and humanity. It is further interpreted as a prophecy regarding Jesus' victory over the devil, with reference to the child of a woman, striking the head of the serpent.[23]

Lucifer[]

The idea of fallen angels was familiar in pre-Christian Hebrew thought from the Book of the Watchers, according to which angels who impregnated human women were cast out of heaven. The Babylonian / Hebrew myth of a rising star, as the embodiment of a heavenly being who is thrown down for his attempt to ascend into the higher planes of the gods, is also found in the Bible (Isaiah 14:12 –15) and was accepted by early Christians, interpreted as a fallen angel.[24]

Aquila of Sinope derives the word helel, the Hebrew name for the morning star, from the verb yalal (to lament). This derivation was adopted as a proper name for an angel who laments the loss of his former beauty.[25] The Christian church fathers — for example Hieronymus, in his Vulgate — translated this as Lucifer. The equation of Lucifer with the fallen angel probably occurred in 1st century Palestinian Judaism.[26] The church fathers brought the fallen lightbringer Lucifer into connection with the Devil on the basis of a saying of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (10.18 EU): "I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning."[27]

In his work De principiis Proemium and in a homily on Book XII, the Christian scholar Origen compared the morning star Eosphorus-Lucifer with the devil. According to Origen, Helal-Eosphorus-Lucifer fell into the abyss as a heavenly spirit after he tried to equate himself with God. Cyprian (around 400), Jerome (around 345 –420),[28] Ambrosius (around 340–397), and a few other church fathers essentially subscribed to this view. They viewed this earthly overthrow of a pagan king of Babylon as a clear indication of the heavenly overthrow of Satan.[29] In contrast, the church fathers Hieronymus, Cyrillus of Alexandria (412–444), and Eusebius (around 260–340) saw in Isaiah's prophecy only the mystified end of a Babylonian king.

Cherub in Eden[]

Most scholars use Ezekiel's cherub in Eden to support the Christian doctrine of the devil.[30]

Ezekiel 28:13 –15: "You were in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone adorned you: ruby, topaz, emerald, chrysolite, onyx, jasper, sapphire, turquoise, and beryl. Gold work of tambourines and of pipes was in you. In the day that you were created they were prepared. You were the anointed cherub who covers: and I set you, so that you were on the holy mountain of God; you have walked up and down in the midst of the stones of fire. You were perfect in your ways from the day that you were created, until unrighteousness was found in you."[31]

This description is used to establish major characteristics of the devil: that he was created good as a high ranking angel, that he lived in Eden, and that he turned evil on his own accord. The Church Fathers argued that, therefore, God is not to be blamed for evil but rather the devil's abuse of his free will.[32]

Belial[]

The term belial (בְלִיַּעַל, bĕli-yaal) with the broader meaning of worthlessness[33] is used through the Old Testament to denote those who are against God or at least against God's order.[34] In Deuteronomy 13:14 those who tempt people into worshiping something other than Yahweh are related to belial. In 1 Samuel 2:12, the sons of Eli are called belial for not recognizing Yahweh and therefore violating sacrifice rituals. In Psalm 18:4 and Psalm 41:8, belial appears in the context of death and disease. In the Old Testament, both Satan and Belial make it difficult for men to live in harmony with God's will.[35]

However, the role of Belial is in opposition to that of Satan: while Belial, representing chaos and death, stands outside of God's cosmos, Satan roams the earth, fighting for the maintenance of the divine order and punishing precisely everything Belial stands for.[36]

However, in the Old Testament, Belial is merely an abstraction and not considered a real independent entity.[37]

Intertestamental Texts[]

Although not part of the canonical Bible, intertestamental writings shaped the early Christian worldview and influenced the interpretation of the Biblical texts. Until the third Century, Christians still referred to these stories to explain the origin of evil in the world.[38] The Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees are still accepted as canonical by the Ethiopian Church.[39] Many Church Fathers accepted this view about fallen angels, though they excluded Satan from these angels. Satan instead, fell after tempting Eve in the Garden of Eden.[40]

Book of Enoch[]

The Book of Enoch, estimated to date from about 300–200 BC, to 100 BC,[41] tells of a group of angels called the Watchers. The Watchers fell in love with human women and descended to earth to have intercourse with them, resulting in giant offspring.[42] On earth, these fallen angels further teach the secrets of heaven like warcraft, blacksmithing, and sorcery.[42] There is no specific devilish leader, as the fallen angels act independently after they descend to earth, but eminent among these angels are Shemyaza and Azazel.[43] Only Azazel is rebuked by the prophet Enoch himself for instructing illicit arts, as stated in 1 Enoch 13:1.[44] According to 1 Enoch 10:6, God sent the archangel Raphael to chain Azazel in the desert Dudael as punishment.

Satan, on the other hand, appears as a leader of a class of angels. Satan is not among the fallen angels but rather a tormentor for both sinful men and sinful angels. The fallen angels are described as "having followed the way of Satan", implying that Satan led them into their sinful ways, but Satan and his angels are clearly in the service of God, akin to Satan in the Book of Job. Satan and his lesser satans act as God's executioners: they tempt into sin, accuse sinners for their misdeeds, and finally execute divine judgment as angels of punishment.[45]

Book of Jubilees[]

The Book of Jubilees also identifies the Bene Elohim ("sons of God") in Genesis 6 with the offspring of fallen angels, adhering to the Watcher myth known from the Book of Enoch. Throughout the book, another wicked angel called Mastema is prominent. Mastema asks God to spare a tenth of the demons and assign them under his domain so that he might prove humanity to be sinful and unworthy. Mastema is the first figure who unites the concept Satan and Belial. Morally questionable actions ascribed to God in the Old Testament, like environmental disasters and tempting Abraham, are ascribed to Mastema instead, establishing a satanic character distant from the will of God in contrast to early Judaism. Still, the text implies that Mastema is a creature of God, although contravening his will. In the end times, he will be extinguished.[46]

New Testament[]

Gospels[]

The devil figures much more prominently in the New Testament and in Christian theology than in the Old Testament and Judaism. The New Testament records numerous accounts of the devil working against God and his plan.

Although in later Christian theology, the devil and his fellow fallen angels are often merged into one category of demonic spirits, the devil is a unique entity throughout the New Testament.[47] The devil is not only a tempter but perhaps rules over the kingdoms of earth.[48] In the temptation of Christ (Matthew 4:8–9 and Luke 4:6–7) the devil offers all kingdoms of the earth to Jesus, implying they belong to him.[49] Since Jesus does not dispute this offer, it may indicate that the authors of those gospels believed this to be true.[49] This interpretation is, however, not shared by all, as Irenaeus argued that, since the devil was a liar since the beginning, he also lied here and that all kingdoms in fact belong to God, referring to Proverbs 21.[50] This event is described in all three synoptic gospels, (Matthew 4:1–11, Mark 1:12–13, and Luke 4:1–13).

Other adversaries of Jesus are ordinary humans although influence by the devil is suggested. John 8:40 speaks about the Pharisees as the "offspring of the devil". John 13:2 states that the devil entered Judas Iscariot before Judas' betrayal. (Luke 22:3)[51] In all three synoptic gospels (Matthew 9:22–29, Mark 3:22–30, and Luke 11:14–20), Jesus' critics accuse him of gaining his power to cast out demons from Beelzebub, the devil. In response, Jesus says that a house divided against itself will fall, so, logically speaking, why would the devil allow one to defeat the devil's works with his own power?[52]

Acts and epistles[]

The Epistle of Jude makes reference to an incident where the Archangel Michael argued with the Devil over the body of Moses.[53] According to the First Epistle of Peter, "Like a roaring lion your adversary the devil prowls around, looking for someone to devour."[54] The authors of the Second Epistle of Peter and the Epistle of Jude believe that God prepares judgment for the devil and his fellow fallen angels, who are bound in darkness until the Divine retribution.[55]

In the Epistle to the Romans the inspirer of sin is also implied to be the author of death.[56] The Epistle to the Hebrews speaks of the devil as the one who has the power of death but is defeated through the death of Jesus.[57][58] In the Second Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul the Apostle warns that Satan disguises as an angel of light.[59]

Revelation[]

The Book of Revelation describes a battle in heaven (Rev 12:7–10) between a dragon/serpent "called the devil, or Satan" and the archangel Michael resulting in the former's fall. Here, the devil is described with features similar to primordial chaos monsters, like the Leviathan in the Old Testament.[60] The image of a serpent identified with Satan verified the identification with the devil and the serpent in Genesis.[61] Thomas Aquinas, Rupert of Deutz and Gregory the Great (among others) interpreted this battle as occurring after the devil sinned by aspiring to be independent of God's will. In consequence, Satan and the evil angels are hurled down from heaven by the good angels under leadership of Michael.[62]

Before Satan was cast down from heaven, he was accusing humans for their sins (Rev 12:10).[63] After 1000 years, the devil would rise again, just to be defeated and cast into the Lake of Fire (Rev 20:10).[64] An angel of the abyss called Abaddon, mentioned in (Rev 9:11), is described as its ruler and often thought as originator of sin and an instrument of punishment, for these reasons also identified with the devil.[65]

Christian teachings[]

Christian tradition and theology identified the myth about a rising star, thrown into the underworld, told about a Babylonian king in the Bible (Isaiah 14:12) with a fallen angel. The concept of fallen angels is of pre-Christian origin. They appear in writings like the Book of Enoch, Book of Jubilees and arguably in the Pentateuch.

As personification of evil, Christians have understood the Devil to be the author of lies and promoter of evil. However, the Devil can go no further than God allows, resulting in the problem of evil. Christian scholars had different opinions on the reason behind evil in the world, and often explained evil in relation to the devil.

The Devil is often identified with Satan, the accuser in the Book of Job.[66] Only rarely, Satan and the Devil are depicted as separate entities.[67]

Liberal Christianity often views the Devil metaphorically. This is true of some Conservative Christian groups too, such as the Christadelphians[68] and the Church of the Blessed Hope. Much of the popular lore of the Devil is not biblical; instead, it is a post-medieval Christian reading of the scriptures influenced by medieval and pre-medieval Christian popular mythology.

Origen[]

Origen was probably the first author to use Lucifer as a proper name for the devil. In his work "De principiis Proemium" and in a homily on Book XII, he compared the morning star Eosphorus-Lucifer — probably based on the Life of Adam and Eve — with the devil or Satan. Origen took the view that Helal-Eosphorus-Lucifer, originally mistaken for Phaeton, fell into the abyss as a heavenly spirit after he tried to equate himself with God. Cyprian (around 400), Ambrosius (around 340–397) and a few other church fathers essentially subscribed to this view, which was borrowed from a Hellenistic myth.[69]

According to Origen, God created rational creatures first, then the material world. The rational creatures are divided into angels and humans, both endowed with free will,[70] and the existence of the material world a result of their choices.[71][72] The world, also inhabited by the devil and his angels, manifests all kinds of destruction and suffering, too. Origen opposed the Valentinian view that suffering in the world is beyond God's grasp and the devil an independent actor. Therefore, the devil is only able to pursue evil as long as God allows. Evil has no ontological reality, but is defined by deficits or a lack of existence, in Origen's cosmology. Therefore, the devil is considered most remote from the presence of God, followed by whose who adhere to his will.[73]

Origen has been accused by Christians of teaching salvation for the devil. However, in defense of Origen, scholars argued apocatastasis for the devil is based on a misinterpretation of his universalism. Accordingly, it is not the devil, as the principle of evil, the personification of death and sin, but the angel, who introduced them in the first place, who will be restored, after this angel abandons his evil will.[74]

Augustine[]

Augustine of Hippo's work Civitas Dei (5th century) became the major opinion of Western demonology including in the Catholic Church.[75] For Augustine, the rebellion of Satan was the first and final cause of evil; thus he rejected earlier teachings about Satan having fallen when the world was already created.[76][77] In his Civitas Dei, he describes two cities (Civitates) distinct from and opposed to each other like light and darkness.[78] The earthly city is caused by the sin of the devil and is inhabited by wicked men and demons (fallen angels) led by the devil. On the other hand, the heavenly city is inhabited by righteous men and the angels led by God.[78] Although his ontological division into two different kingdoms shows a resemblance to Manichean dualism, Augustine differs in regard to the origin and power of evil. He argues that evil came first into existence by the free will of the devil[79] and has no independent ontological existence. Augustine always emphasized the sovereignty of God over the devil[80] who can only operate within his God-given framework.[77]

Unlike humans, the devil along with his demons only have one choice and can not repent their sin, since their sin does not root in temptation but in their very own choice, which defines their nature.[81][82] Since the sin of the devil is intrinsic to his nature, Augustine argues that the devil must have turned evil immediately after his creation.[83] Thus the devil's attempt to take God's throne is not an assault on the gates of heaven, but a turn to solipsism in which the devil becomes God in his world.[84] Further, Augustine rejects the idea that envy could have been the first sin (as some early Christians believed, evident from sources like Cave of Treasures in which Satan has fallen because he envies humans and refused to prostrate himself before Adam), since pride ("loving yourself more than others and God" ) is required to be envious ("hatred for the happiness of others").[85] Such sins are described as removal from God's presence. The devil's sin does not give evil a positive value, since evil is, according to Augustine, merely a byproduct of creation. The spirits have all been created in the love of God but the devil valued himself more, thereby abandoning his position for a lower good. Less clear is Augustine about the reason for the devil's choosing to abandon God's love. In some works, he argued that it is God's grace that gives the angels a deeper understanding of God's nature and the order of the cosmos. Illuminated by God-given grace, they became incapable of feeling any desire for sin. The other angels, however, are not blessed with grace and act sinfully.[86]

Anselm of Canterbury[]

Anselm of Canterbury describes the reason for the Devils' fall in his De Casu Diaboli ("On the Devil's Fall"). Breaking with Augustine's diabology, he absolved God from pre-determinism and causing the devil to sin. Like earlier theologians, Anselm explained evil as nothingness or something people can merely ascribe to something to negate its existence, but has no substance in itself. God gave the devil free will but has not caused the devil to sin by creating the condition to abuse this gift. Anselm invokes the idea of grace, bestowed upon the angels.[87] According to Anselm, grace was also offered to Lucifer but the devil willingly refused to receive the gift from God. Anselm argues further that all rational creatures strive for good since it is the definition of good to be desired by rational creatures, so Lucifer's wish to become equal to God is actually in accordance with God's plan.[88][b] The devil deviates from God's plans when he wishes to become equal to God by his own efforts without relying on God's grace.

Anselm also played an important role in shifting Christian theology further away from the ransom theory of atonement, the belief that Jesus' crucifixion was a ransom paid to Satan, in favor of the satisfaction theory.[90] According to this view, humanity sinned by violating the cosmic harmony God created. To restore this harmony, humanity needed to pay something they did not owe to God. But since humans could not pay the price, God had to send Jesus, who is both God and human, to sacrifice himself.[91] The devil does not play an important role in this theory of atonement any longer. In Anselm's theology, the devil features more as an example of the abuse of free will than as a significant actor in the cosmos.[92] He is not necessary to explain either the fall or the salvation of humanity.[93]

History[]

Early Christianity[]

The notion of fallen angels already existed in Pre-Christian times, but had no unified narrative. In 1 Enoch, Azazel and his host of angels came to earth in human shape and taught forbidden arts resulting in sin. In the Apocalypse of Abraham Azazel is described with his own Kavod (Magnificence), a term usually used for the Divine in apocalyptic literature, already indicating the devil as anti-thesis of God, with the devil's kingdom on earth and God's kingdom in heaven.[94] In the Life of Adam and Eve Satan was cast out of heaven for his refusal to prostrate himself before man, likely the most common explanation for Satan's fall in Proto-orthodox Christianity.[95]

Christianity, however, depicted the fall of angels as an event prior to the creation of humans. The devil becomes considered a rebel against God, by claiming divinity for himself; he is allowed to have temporary power over the world. Thus, in prior depictions of the fallen angels, the evil angel's misdemeanor is directed downwards (to man on earth) while, with Christianity, the devil's sin is directed upwards (to God).[96] Although the Devil is considered to be inherently evil, most Christian scholars agree that the Devil had been created good but, at some point, freely chosen evil, resulting in his fall.

In early Christianity, some movements postulated a distinction between the God of Law, creator of the world and the God of Jesus Christ. Such positions were held by Marcion, Valentinus, the Basilides and Ophites, who denied the Old Testamental deity to be the true God, arguing that the descriptions of the Jewish deity are blasphemous for God. They were opposed by those who argued that the deity presented by Jesus and the God of Jews are the same, like Irenaeus, Tertullian and Origen, who in turn accused such movements as blaspheming against God by asserting a power higher than the Creator. As evident from Origen's On the First Principles, those who denied the Old Testamental deity to be the true God argued that God can only be good and cannot be subject to inferior emotions like anger and jealousy. Instead, they accused him of self-deification, thus identifying him with Lucifer (Helel), the opponent of Jesus and ruler of the world.[97] However, not all dualistic movements equated the Creator with the devil. In Valentinism, the Creator is merely ignorant, but not evil, trying to fashion the world as good as he can, but lacking the proper power maintain its goodness.[98] Irenaeus writes in Against Heresies that, according to the Valentinian cosmological system, Satan was the left-hand ruler,[99] but actually superior to the Creator, because he would consist of spirit, while the Creator of inferior matter.[100][98]

Byzantium[]

Byzantine understanding of the devil derives mostly from the fathers of the first five centuries. Due to the focus on monasticsm, mysticism and negative theology, which were more unifying than Western traditions, the devil played only a marginal role in Byzantine theology.[102] Within such monistic cosmology, evil was considered as a deficiency having no real ontological existence. Thus the devil became the entity most remote from God, as described by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.[103]

John Climacus detailed the traps of the devil in his monastic treatise The Ladder of Paradise. The first trap of the devil and his demons is to prevent people from performing good actions. In the second, one performs good but not in accordance with God's will. In the third, one becomes proud of one's good actions. Only by recognizing that all the good that one can perform comes from God can the last and most dangerous trap be avoided.

John of Damascus, whose works also affected Western scholastic traditions, provided a rebuttal to Dualistic cosmology. Against dualistic religions like Manichaeism, he argued that, if the devil was a principle independent from God and there are two principles, they must be in complete opposition. But if they exist, according to John, they both share the trait of existence, resulting in only one principle (of existence) again.[104] Influenced by John the Evangelist, he further emphasized the metaphors of light for good and darkness for evil.[105] Like darkness, deprivation of good results in one's becoming non-existent and darker.

Byzantine theology does not consider the devil as redeemable. Since the devil is a spirit, the devil and his angels cannot have a change in their will, just as humans turned into spirits after death are not able to change their attitude either.[106]

Anglo-Saxon period[]

Although the teachings of Augustine, who rejected the Enochian writings and associated the devil with pride instead of envy, are usually considered the fundamental depictions of the devil in Medieval Christianity, some concepts, like regarding evil as the mere absence of good, were far too sophisticated to be represented by most theologians during the Anglo-Saxon period. They sought a more concrete image of evil to represent spiritual struggle and pain, so the devil became more of a concrete entity. From the fourth through the twelfth century, Christian ideas combined with European pagan beliefs, creating a vivid folklore about the devil, introducing new elements. Although theologians usually conflated demons, satans and the devil, Anglo-Saxon demonology fairly consistently distinguished between Lucifer, the fallen angel fixed in hell, and the mobile Satan executing his will.[107]

Teutonic gods were often considered demons or even the devil. In the Flateyjarbók, Odin is explicitly described as another form of the devil, whom the pagans worshiped and to whom they sacrificed.[108] Everything sacred to pagans or the foreign deities was usually perceived as sacred for the devil and feared by Christians.[109] Many pagan nature spirits like dwarfs and elves became seen as demons, although a difference remained between monsters and demons. The monsters, regarded as distorted humans, probably without souls, were created so that people might be grateful to God that they did not suffer in such a state; they ranked above demons in existence and still claimed a small degree of beauty and goodness as they had not turned away from God.[110]

It was widely accepted that people could make a deal with the devil[111] by which the devil would attempt to catch the soul of a human. Often, the human would have to renounce faith in Christ. But the devil could easily be tricked by courage and common sense and therefore often remained as a comic relief character in folkloric stories.[112] In many German folktales, the devil replaces the role of a deceived giant, known from pagan tales.[113] In some legends the devil is linked to church building. The devil demands the soul of the very first creature who enters the completed church, whereupon the believers sent a goat or a dog to pass first and the devil is cheated.

Pope Gregory the Great's doctrines about the devil became widely accepted during the Medieval period and, combined with Augustine's view, became the standard account of the devil. Gregory described the devil as the first creation of God. He was a cherub and leader of the angels (contrary to the Byzantine writer Pseudo-Dionysius, who did not place the devil among the angelic hierarchy).[114] Gregory and Augustine agreed with the idea that the devil fell because of his own will. Nevertheless, God holds ultimate control over the cosmos. To support his argument, Gregory paraphrases parts of the Old Testament according to which God sends an evil spirit. However, the devils' will is indeed unjust; God merely diverts the evil deeds to justice.[115] For Gregory, the devil is thus also the tempter. The tempter incites, but it is the human will that consents to sin. The devil is only responsible for the first stage of sinning.[101]

Cathars and Bogomiles[]

The revival of dualism in the 12th century by Catharism, deeply influenced Christian perceptions on the devil.[116] What is known of the Cathars largely comes in what is preserved by the critics in the Catholic Church which later destroyed them in the Albigensian Crusade. Alain de Lille, c.1195, accused the Cathars of believing in two gods, one of light and one of darkness.[117] Durand de Huesca, responding to a Cathar tract c.1220 indicates that they regarded the physical world as the creation of Satan.[118] A former Italian Cathar turned Dominican, Sacchoni in 1250 testified to the Inquisition that his former co-religionists believed that the Devil made the world and everything in it.[119]

Catharism probably roots in Bogomilism, founded by Theophilos in the 10th century, who in turn owed many ideas to the earlier Paulicians in Armenia and the Near East and had strong impact on the history of the Balkans. Their true origin probably lies within earlier sects such as Nestorianism, Marcionism and Borborites, who all share the notion of a docetic Jesus. Like these earlier movements, Bogomilites agree upon a dualism between body and soul and a struggle between good and evil. Rejecting most of the Old Testament, they opposed the established Catholic Church whose deity they considered to be the devil. Among the Cathars, there have been both an absolute dualism (shared with Bogomilites and early Christian Gnosticism) and mitigated dualism as part of their own interpretation. Mitigated dualists are closer to Christianity, regarding Lucifer as an angel created (although through emanation, since by rejecting the Old Testament, they rejected creation ex nihilo) by God, who fell because of his own will. On the other hand, absolute dualists regard Lucifer as the eternal principle of evil, not part of God's creation. Lucifer forced the good souls into bodily shape, and imprisoned them in his kingdom. Following the absolute dualism, neither the souls of the heavenly realm nor the devil and his demons have free will but merely follow their nature, thus rejecting the Christian notion of sin.[120] The Catholic church reacted to spreading dualism in the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215), by affirming that God created everything from nothing; that the devil and his demons were created good, but turned evil by their own will; that humans yielded to the devil's temptations, thus falling into sin; and that, after Resurrection, evil people will suffer along with the devil, while good people enjoy eternity with Christ.[121] Only a few theologians from the University of Paris in 1241, proposed the contrary assertion, that God created the devil evil and without his own decision.[122]

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, there are still remaining parts of Bogomil Dualism in Balkan folklore. Before God created the world, he meets a goose on the eternal ocean. The name of the Goose is reportedly named Satanael and claims to be a god. When God asks Satanael, who he himself is, the devil answers "the god of gods". God requests the devil to dive to the bottom of the sea to carry some mud then. From this mud, they fashioned the world; God created his angels and the devil his demons. Later, the devil tries to assault god but is thrown into the abyss, lurking on the creation of God and planning another attack on heaven.[123] This myth shares same resemblance with Pre-Islamic Turkic creation myths, as well as Bogomilite thoughts.[124]

The Reformation[]

Since the beginning of the early modern period, Christians started to imagine the devil as an increasingly powerful entity, constantly leading people into falsehood. Jews, witches, heretics and people affected by leprosy were often associated with the devil.[125] The Malleus Maleficarum, the most extensive work on witch-hunt, was written in 1486. Protestants began to accuse the Catholic church of teaching false doctrines and unwillingly falling for the traps of the devil. Both Catholics and Protestants reformed Christian society by shifting the major concerns from avoiding the seven deadly sins to observing the Ten Commandments.[126] Thus disloyalty and idolatry became greatest sin and the devil increasingly dangerous. Simultaneously, some reform movements and early humanists often rejected the concept of a personal devil and dismissed belief in the devil as superstition.

Early Protestant thought[]

Luther taught the real, personal and powerful Devil.[127] Evil was not a deficit of good, but the presumptuous will against God, his word and his creation.[128] He also affirmed the reality of witchcraft caused by the devil. However, he denied the reality of witches' flight and metamorphoses, regarded as imagination instead.[c] The devil could also possess someone. He opined that the possessed might feel the devil in himself, as a believer feels the Holy Spirit in his body.[d] In his , Luther lists several hosts of greater and lesser devils. Greater devils would incite to greater sins, like unbelief and heresy, while lesser devils to minor sins like greed and fornication. Among these devils also appears Asmodeus known from the Book of Tobit.[e] Luther's view, however, is in contrast with most protestant preachers, who merged the anthropomorphic devils into only one unit of evil. They argue that Luther himself merely used these anthropomorphic devils as stylistic devices for his audience, although they are different manifestations of one spirit.[f]

Calvin taught the traditional view of the Devil as a fallen angel. Calvin repeats the simile of Saint Augustine: "Man is like a horse, with either God or the Devil as rider."[131] In interrogation of Servetus who had said that all creation was part of God, Calvin asked: what of the Devil? Servetus responded "all things are a part and portion of God".[132]

Protestants regarded the teachings of the Catholic Church undermined by Satan's agency, replacing the teachings of the Bible with invented customs. Unlike heretics and witches, Catholics would follow Satan unconsciously.[133] Abandoning ceremonial rituals and intercession, upheld by the Catholic Church, reformers emphasized individual resistance against the temptations of the devil.[134] Among Luther's teachings to ward off the devil was a recommendation of music since "the Devil cannot stand gaiety."[135]

Anabaptists and Dissenters[]

David Joris was the first of the Anabaptists to venture that the Devil was only an allegory (c.1540); his view found a small but persistent following in the Netherlands.[136] The devil, as a fallen angel, would simply symbolize Adam's fall from God's grace and Satan as a power within man.[137]

The view was transmitted to England and Joris's booklet was reprinted anonymously in English in 1616, prefiguring a spate of non-literal Devil interpretations in the 1640s-1660s: Mede, Bauthumley, Hobbes, Muggleton and the private writings of Isaac Newton.[138] In Germany such ideas surfaced later, c.1700, among writers such as Balthasar Bekker and Christian Thomasius.

However the above views remained very much a minority. Daniel Defoe in his The Political History of the Devil (1726) describes such views as a form of "practical atheism". Defoe wrote "that to believe the existence of a God is a debt to nature, and to believe the existence of the Devil is a like debt to reason".[139]

In the Modern Era[]

With increasing influence of positivism, scientism and nihilism in the modern era, both the concept of God and the Devil became less relevant and most educated people doubted the existence of any spiritual entity. Many Christian theologians interpreted the devil within its cultural context as a symbol of psychological forces. Many dropped the concept of the devil as an unnecessary assumption: the devil does not add much to solve the problem of evil since, whether or not the angels sinned before men, the question remains how evil entered the world in the first place. Evil could best be explained as human sin.[140]

Rudolf Bultmann taught that Christians need to reject belief in a literal Devil as part of 1st century culture.[141] This line is developed by Walter Wink.[142]

In contrast, the works of writers like Jeffrey Burton Russell retain the belief in a literal personal fallen being of some kind. In Lucifer: the Devil in the Middle Ages, the third volume of his five-volume history of the Devil,[143] Russell argues that theologians who reject a literal devil (like Bultmann, unnamed) overlook the fact that the Devil is part and parcel of the New Testament from its origins.

Karl Barth describes the devil neither as a person nor as a merely psychological force but as nature opposing good. He includes the devil in his threefold cosmology: there is God, God's creation, and nothingness. Nothingness is not absence of existence, but a plane of existence in which God withdraws his creative power. It is depicted as chaos opposing real being, distorting the structure of the cosmos and gaining influence over humanity. In contrast to dualism, Barth argued that opposition to reality entails reality so that the existence of the devil depends on the existence of God and is not an independent principle.[144]

Contemporary views[]

Catholic Church[]

While the Catholic Church has not paid much attention to the devil in the modern period, contemporary Catholic teachings have begun to re-emphasize the devil.[g]

Pope Paul VI expressed concern about the influence of the Devil and in 1972 stated that: "Satan's smoke has made its way into the Temple of God through some crack".[146] However, John Paul II viewed the defeat of Satan as inevitable.[147]

Pope Francis brought renewed focus on the Devil in the early 2010s, stating, among many other pronouncements, that "The devil is intelligent, he knows more theology than all the theologians together."[148] Thomas Rosica and journalist Cindy Wooden commented on the pervasiveness of the devil in Pope Francis' teachings, and both say that Francis believes that the devil is real.[149][150] During a morning homily in the chapel of the Domus Sanctae Marthae, in 2013, Pope Francis said:[151]

The Devil is not a myth, but a real person. One must react to the Devil, as did Jesus, who replied with the word of God. With the prince of this world one cannot dialogue. Dialogue is necessary among us, it is necessary for peace [...]. Dialogue is born from charity, from love. But with that prince one cannot dialogue; one can only respond with the word of God that defends us.

In 2019, Arturo Sosa, superior general of the Society of Jesus, said that Satan is a symbol, the personification of evil, but not a person and not a "personal reality"; four months later, he said that the Devil is real, and his power is a malevolent force.[152]

Unitarians and Christadelphians[]

Some Christian groups and individuals view the Devil in Christianity figuratively. They see the Devil in the Bible as representing human sin and temptation, and any human system in opposition to God. Early Bible fundamentalist Unitarians and Dissenters like Nathaniel Lardner, Richard Mead, Hugh Farmer, William Ashdowne and John Simpson, and John Epps taught that the miraculous healings of the Bible were real, but that the Devil was an allegory, and demons just the medical language of the day. Such views today are taught today by Christadelphians[153] and the Church of the Blessed Hope. Simpson went so far, in his Sermons (publ. posthumously 1816), as to comment that the Devil was "really not that bad", a view essentially echoed as recently as 2001 by Gregory Boyd in Satan and the Problem of Evil: Constructing a Trinitarian Warfare Theodicy.

Charismatic movements[]

Charismatic movements regard the devil as a personal and real character, rejecting the increasing metaphorical and historical reinterpretation of the devil in the modern period as unbiblical and contrary to the life of Jesus. People who surrender to the kingdom of the devil are in danger of becoming possessed by his demons.[154]

By denomination[]

Catholicism[]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that the Church regards the Devil as being created as a good angel by God, and by his and his fellow fallen angels' free will, fell out of God's grace.[155][156] Satan is not an infinitely powerful being. Although he is an angel, and thus pure spirit, he is considered a creature nonetheless. Satan's actions are permitted by divine providence.[156] Catholicism rejects Apocatastasis, the reconciliation with God suggested by the Church Father Origen.[157]

A number of prayers and practices against the Devil exist within Catholic Church tradition.[158][159] The Lord's Prayer includes a petition for being delivered "from the evil one", but a number of other specific prayers also exist.

The Prayer to Saint Michael specifically asks for Catholics to be defended "against the wickedness and snares of the Devil." Given that some of the messages from Our Lady of Fatima have been linked by the Holy See to the "end times",[160] some Catholic authors have concluded that the angel referred to within the Fatima messages is St. Michael the Archangel who defeats the Devil in the War in Heaven.[161][162] Author Timothy Robertson takes the position that the Consecration of Russia was a step in the eventual defeat of Satan by the Archangel Michael.[163]

The process of exorcism is used within the Catholic Church against the Devil and demonic possession. According to The Catechism of the Catholic Church, "Jesus performed exorcisms and from him the Church has received the power and office of exorcising".[164] Gabriele Amorth, the chief exorcist of the Diocese of Rome, warned against ignoring Satan, saying, "Whoever denies Satan also denies sin and no longer understands the actions of Christ".[165]

The Catholic Church views the battle against the Devil as ongoing. During a 24 May 1987 visit to the Sanctuary of Saint Michael the Archangel, Pope John Paul II said:[165]

The battle against the Devil, which is the principal task of Saint Michael the archangel, is still being fought today, because the Devil is still alive and active in the world. The evil that surrounds us today, the disorders that plague our society, man's inconsistency and brokenness, are not only the results of original sin, but also the result of Satan's pervasive and dark action.

Eastern Orthodox views[]

In Eastern Orthodoxy, the devil is an integral part of Christian cosmology. The existence of the devil is taken seriously and not subject to questions.[166] According to Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition, there are three enemies of humanity: Death, Sin and Satan.[167] In contrast to Western Christianity, sin is not viewed as a deliberate choice but as a universal and inescapable weakness.[168] Sin is turning from God towards oneself, a form of egoism and ungratefulness, leading away from God towards death and nothingness.[169] Lucifer invented sin, resulting in death, and introduced it first to the angels, who have been created before the material world, and then to humanity. Lucifer, considered a former radiant archangel, lost his light after his fall and became the dark Satan (the enemy).[170]

Eastern Orthodoxy maintains that God did not create death, but that it was forged by the devil through deviance from the righteous way (a love of God and gratitude).[171] In a sense, it was a place where God was not, for He could not die, yet it was an inescapable prison for all humanity until the Christ. Before Christ's Resurrection, it could be said that humanity had a reason to fear Satan. He was a creature could separate us from the Creator and source of life — for God could not enter Hades, and humanity could not escape it.

Once in Hades, the Orthodox hold that Christ — being good and just — granted life/resurrection to all who wanted to follow him. As a result, Satan has been overthrown and is no longer able to hold humanity. With the prison despoiled, the only power Satan has is the power each individual gives him. With free will, if one wants to follow Satan, one may. This is what led St. Jerome to say, "Only rebels remain in graves."[172]

Evangelical Protestants[]

Evangelical Protestants agree that Satan is a real, created being entirely given over to evil and that evil is whatever opposes God or is not willed by God. Evangelicals emphasize the power and involvement of Satan in history in varying degrees; some virtually ignore Satan and others revel in speculation about spiritual warfare against that personal power of darkness.[173] Protestants are much less concerned with the cause of devil's fall, and do not deal with an angelic hierarchy,[174] since it is thought as neither useful nor necessary to know.[175]

Jehovah's Witnesses[]

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that Satan was originally a perfect angel who developed feelings of self-importance and craved worship that belonged to God. Satan persuaded Adam and Eve to obey him rather than God, raising the issue—often referred to as a "controversy"—of whether people, having been granted free will, would obey God under both temptation and persecution. The issue is said to be whether God can rightfully claim to be sovereign of the universe.[176][177] Instead of destroying Satan, God decided to test the loyalty of the rest of humankind and to prove to the rest of creation that Satan was a liar.[178][179] Jehovah's Witnesses believe that Satan is God's chief adversary[179] and the invisible ruler of the world.[176][177] They believe that demons were originally angels who rebelled against God and took Satan's side in the controversy.[180]

Jehovah's Witnesses do not believe that Satan lives in Hell or that he has been given responsibility to punish the wicked. Satan and his demons are said to have been cast down from Heaven to Earth in 1914, marking the beginning of the "last days".[176][181] Witnesses believe that Satan and his demons influence individuals, organizations and nations, and that they are the cause of human suffering. At Armageddon, Satan is to be bound for 1,000 years, and then given a brief opportunity to mislead perfect humanity before being destroyed.[182]

Latter Day Saints[]

In Mormonism, the Devil is a real being, a literal spirit son of God who once had angelic authority, but rebelled and fell prior to the creation of the Earth in a premortal life. At that time, he persuaded a third part of the spirit children of God to rebel with him. This was in opposition to the plan of salvation championed by Jehovah (Jesus Christ). Now the Devil tries to persuade mankind into doing evil.[183] Mankind can overcome this through faith in Jesus Christ and obedience to the Gospel.[184]

Latter Day Saints traditionally regard Lucifer as the pre-mortal name of the Devil. Mormon theology teaches that in a heavenly council, Lucifer rebelled against the plan of God the Father and was subsequently cast out.[185] Mormon scripture reads:

And this we saw also, and bear record, that an angel of God who was in authority in the presence of God, who rebelled against the Only Begotten Son whom the Father loved and who was in the bosom of the Father, was thrust down from the presence of God and the Son, and was called Perdition, for the heavens wept over him—he was Lucifer, a son of the morning. And we beheld, and lo, he is fallen! is fallen, even a son of the morning! And while we were yet in the Spirit, the Lord commanded us that we should write the vision; for we beheld Satan, that Old Serpent, even the Devil, who rebelled against God, and sought to take the kingdom of our God and his Christ—Wherefore, he maketh war with the saints of God, and encompasseth them round about.[186]

After becoming Satan by his fall, Lucifer "goeth up and down, to and fro in the earth, seeking to destroy the souls of men".[187] Mormons consider Isaiah 14:12 to be referring to both the king of the Babylonians and the Devil.[188][189]

Theological disputes[]

Angelic hierarchy[]

The devil might either be a cherub or a seraph. Christian writers were often undecided from which order of the angels the devil fell. While the devil is identified with the cherub in Ezekiel 28:13–15, this conflicts with the view that the devil was among the highest angels, who are, according to Pseudo-Dionysius, the seraphim.[190] Thomas Aquinas quotes Gregory the Great who stated that Satan "surpassed [the angels] all in glory".[191] Arguing that the higher an angel stood the more likely he was to become guilty of pride,[192][193] the devil would be a seraph. But Aquinas held sin incompatible with the fiery love characteristic of a seraph, but possible for a cherub, whose primary characteristic is fallible knowledge. He concludes, in line with Ezekiel, that the devil was the most knowledgeable of the angels, a cherub.[194]

Hell[]

Christianity is undecided whether the devil fell immediately into hell or if he is given respite until the Day of Judgment.[195] Several Christian authors, among them Dante and Milton, have depicted the devil as resident in Hell. This is in contrast to parts of the Bible that describe the devil as traveling about the earth, like Job 1:6–7 and 1 Peter 5:8, discussed above. At least acording to Revelation 20:10 the devil is thrown into the Lake of Fire and Sulfur. Theologians disagree whether the devil roams the air of the earth or fell underground into hell. Yet all Christian theologians agree that the devil will be in hell after Judgment Day.

If the devil is bound in hell, the question arises how he can still appear to people on earth. In some literature, the devil only sends his lesser demons or Satan to execute his will, while he remains chained in hell.[196] Others assert that the devil is chained but takes his chains with him when he rises to the surface of the eath.[197] Gregory the Great tried to resolve this conflict by stating that, no matter where the devil dwells spatially, separation from God itself is a state of hell.[198]

Sinfulness of angels[]

Some theologians believe that angels cannot sin because sin brings death and angels cannot die.[199]

Supporting the idea that an angel may sin, Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologiae Question 63 article 1, wrote:

An angel or any other rational creature considered in his own nature, can sin; and to whatever creature it belongs not to sin, such creature has it as a gift of grace, and not from the condition of nature. The reason of this is, because sinning is nothing else than a deviation from that rectitude which an act ought to have; whether we speak of sin in nature, art, or morals. That act alone, the rule of which is the very virtue of the agent, can never fall short of rectitude. Were the craftsman's hand the rule itself engraving, he could not engrave the wood otherwise than rightly; but if the rightness of engraving be judged by another rule, then the engraving may be right or faulty.

He further divides angelic orders, as distinguished by Pseudo-Dionysius, into fallible and infallible based whether the Bible mentions them in relation to the demonic or not. He concludes that because seraphim (the highest order) and thrones (the third-highest) are never mentioned as devils, they are unable to sin. On the contrary, the Bible speaks about cherubim (the second-highest order) and powers (the sixth-highest) in relation to the devil. He concludes that attributes represented by the infallible angels, like charity, can only be good, while attributes represented by cherubim and powers can be both good and bad.[200]

Aquinas concludes that angels as intellectual creatures cannot succumb to bodily desires, they can sin as result of their mind-based will.[201] The sins attributed to the devil include pride, envy, and even lust, for Lucifer loved himself more than everything else. Initially, after the angels realized their existence, they decided for or against dependence on God, and the good and evil angels were separated from each other after a short delay following their creation.[202] Similarly, Peter Lombard writes in his Sentences, angels were all created as good spirits, had a short interval of free-decision and some choose love and have thus been rewarded with grace by God, while others choose sin (pride or envy) and became demons.[203]

Iconography and literature[]

Images[]

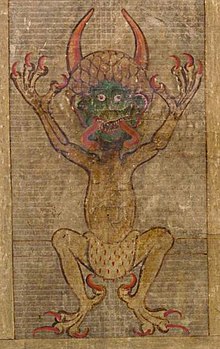

The earliest representation of the devil might be a mosaic in San Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna from the sixth century, in the form of a blue angel.[204] Blue and violet were common colors for the devil in the early middle ages, reflecting his body composed of the air below the heavens, considered to consist of thicker material than the ethereal fire of heavens the good angels are made from and thus colored red. The devil's first appearance as black rather than blue was in the ninth century. Only later did the devil became associated with the color red to reflect blood and the fires of hell.[205]

Before the eleventh century, the devil was often shown in art as either a human or a black imp. The humanoid devil often wore white robes and feathered bird-like wings or appeared as an old man in a tunic.[206] The imps were depicted as tiny misshapen creatures. When humanoid features were combined with monstrous ones during the eleventh century, the imp's monstrosity gradually developed into the grotesque.[207] Horns became a common motif starting in the eleventh century. The devil was often depicted as naked wearing only loincloths, symbolizing sexuality and wildness.[208]

Particularly in the medieval period, the devil was often shown as having horns and a goat's hindquarters and with a tail. He was also depicted as carrying a pitchfork,[209] the implement used in Hell to torment the damned, which derives in part from the trident of Poseidon.[210] Goat-like images resemble the Ancient Greek Deity Pan.[210] Pan in particular looks very much like the European devil in the late Medieval Age. It is unknown if these features are directly taken from Pan or whether Christians coincidentally devised an image similar to Pan.[211] Depiction of the devil as a satyr-like creature is attested since the eleventh century.[212]

Dante's Inferno[]

The portrayal of the devil in Dante Alighieri's Inferno reflects early Christian Neo-Platonic thought. Dante structures his cosmology morally; God is beyond heaven and the devil at the bottom of hell beneath the earth. Imprisoned in the middle of the earth, the devil becomes the center of the material and sinful world to which all sinfulness is drawn. In opposition to God, which is portrayed by Dante as a love and light, Lucifer is frozen and isolated in the last circle of hell. Almost motionless, more pathetic, foolish, and repulsive than terrifying, the devil represents evil[213] in the sense of lacking substance. In accordance with Platonic/Christian tradition, his gigantic appearance indicates a lack of power, as pure matter was considered the farthest from God and closest to nonbeing.[214]

The devil is described as a huge fiend, whose buttocks are frozen in ice. He has three faces, chewing on the three traitors Judas, Cassius and Brutus. Lucifer himself is also accused of treason for turning against his Creator. Below each of his faces, Lucifer has a pair of bat-wings, another symbol of darkness.[215]

John Milton in Paradise Lost[]

In John Milton's Renaissance epic poem Paradise Lost, Satan is one of the main characters, perhaps an anti-hero.[216] In line with Christian theology, Satan rebelled against God and was subsequently banished from heaven along with his fellow angels. Milton breaks with previous authors who portray Satan as a grotesque figure;[217] instead, he becomes a persuasive and charismatic leader who, even in hell, convinced the other fallen angels to establish their own kingdom. It is unclear whether Satan is a hero turning against an unjust ruler (God) or a fool who leads himself and his followers into damnation in a futile attempt to become equal to God. Milton uses several pagan images to depict the demons, and Satan himself arguably resembles the ancient legendary hero Aeneas.[218] Satan is less the devil as known from Christian theology than a morally ambivalent character with strengths and weaknesses, inspired by the Christian devil.[219]

See also[]

- Angra Mainyu

- Demiurge

- Devil in popular culture - includes references to Milton's Paradise Lost, Goethe's Faust, C. S. Lewis's The Screwtape Letters, etc.

- Dystheism

- Evil demon

- Exorcism in Christianity

- Gallu

- Misotheism

- Mara (demon)

- Prayer to Saint Michael

- Shaitan

- The Devil's Farmhouse

- Yaoguai

Notes[]

- ^ "By desiring to be equal to God in his arrogance, Lucifer abolishes the difference between God and the angels created by him and thus calls the entire system of order into question (if he were instead to replace God, the system itself would only be preserved with reversed positions)" Original: "Indem Luzifer in seinem Hochmut Gott gleich sein will, hebt er die Differenz zwischen Gott und den von diesem geschaffenen Engeln auf und stellt damit das gesamte Ordnungssystem in Frage (würde er sich statt dessen an die Stelle Gottes setzen, bliebe das System selbst erhalte, nur mit vertauschten Positionen)."[1]

- ^ "The striving of the rational creatures for equality with God corresponds entirely to the divine will to create if it is pursued because it corresponds to the will of God. This is exactly where the 'disorder' of the will of Lucifer lies: He equates himself with God because he does it of his own Will (propria voluntas), which was not subordinate to anyone, wanted." Original: "Das Streben der rationalen Geschöpfe nach Gottgleichheit entspricht durchaus dem göttlichen Schöpfungswillen, wenn es verfolgt wird, weil es dem Willen Gottes entspricht. Genau hierin liegt die "Unordnung" des Willen Luzifers: Er setzt sich mit Gott gleich, weil er es aus dem eigenem Willen (propria voluntas), der sich niemandem unterordnete, wollte."[89]

- ^ "However, the reformer rejects the reality of witches' flight or the transformation and metamorphosis of people into other forms and ascribed such ideas not to the devil, but to human imagination" Original: "Allerdings lehnt der Reformator die Realität des Hexenfluges bzw. der Verwandlung und Metamorphosen des Menschen in andere Gestalten ab und schrieb solche Vorstellungen nicht dem Teufel, sondern der menschlichen Einbildungskraft zu."[129]

- ^ "The reformer thinks of the possession of the devil as a possibility and he feels how he fills the human body, similar to how he feels the divine spirit for himself and thus regards himself as an instrument of God." Original: "Die Besessenheit durch den Teufel denkt der Reformator als eine Möglichkeit, wie der Teufel den Körper des Menschen ausfüllt, ähnlich wie er sich selbst den göttlichen Geist fühl und sich so als ein Instrument Gottes betrachtet."[129]

- ^ "The reformer interprets the book of Tobit as a drama in which Asmodeus is up to mischief as a house devil." Original: "Beispielsweise interpretiert der Reformer das Buch Tobit als ein Drama, in dem Asmodeus als Hausteufel sein Unwesen treibe."[129]

- ^ "Thus Luther's use of individual specific devils is explained by the need to present his thoughts in a manner that is reasonable and understandable for the masses of his contemporaries." Original: "So erklärt sich auch die Verwendung einzelner Spezialteufel bei Luther aus der Notwendigkeit, seine Gedanken in einer der Massse seiner Zeitgenossen gemäßigen und verständlichen Art darzustellen."[130]

- ^ "The success of fundamentalist groups on the fringes of the Catholic Church is just as much a part of the success story of the "resurrected" evil, as is its position in non-Catholic sects and free churches." Original: "Der Erfolg von fundamentalistischen Gruppierungen auch am Rande der katholischen Kirche gehört ebenso zu der Erfolgsgeschichte des "wiederauferstandenen" Bösen wie seine Position in nicht-katholische Sekten und Freikirchen."[145]

References[]

- ^ Achim Geisenhanslüke, Georg Mein Monströse Ordnungen: Zur Typologie und Ästhetik des Anormalen transcript Verlag, 31.07.2015 ISBN 9783839412572 p. 217 (German)

- ^ McCurry, Jeffrey. "Why the Devil Fell: A Lesson in Spiritual Theology From Aquinas's Summa Theologiae." New Blackfriars, vol. 87, no. 1010, 2006, p. 389 JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43251053. Accessed 5 May 2021.

- ^ Hans-Werner Goetz Gott und die Welt. Religiöse Vorstellungen des frühen und hohen Mittelalters. Teil I, Band 3: IV. Die Geschöpfe: Engel, Teufel, Menschen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 12.09.2016 ISBN 9783847005810 p. 221

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 pp. 94 –95

- ^ Kelly 2006, pp. 1–13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Campo 2009, p. 603.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kelly 2006, pp. 1–13, 28–29.

- ^ ed. Buttrick, George Arthur; The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, An illustrated Encyclopedia

- ^ Stephen M. Hooks – 2007 "As in Zechariah 3:1–2 the term here carries the definite article (has'satan="the satan") and functions not as a...the only place in the Hebrew Bible where the term "Satan" is unquestionably used as a proper name is 1 Chronicles 21:1."

- ^ Coogan, Michael D.; A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kelly 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kelly 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits (Rev. ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 1-59244-531-4. OCLC 56727898.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 37

- ^ Stokes, Ryan E. "The Devil Made David Do It ... or 'Did' He? The Nature, Identity, and Literary Origins of the 'Satan' in 1 Chronicles 21:1." Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 128, no. 1, 2009, pp. 91–106. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25610168. Accessed 17 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kelly 2006, p. 24.

- ^ M. D. Goulder The Psalms of the return (book V, Psalms 107 –150) 1998 p. 197 "The vision of Joshua and the Accuser in Zechariah 3 seems to be a reflection of such a crisis."

- ^ Stokes, Ryan E. "Satan, Yhwh's Executioner." Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 133, no. 2, 2014, pp. 251–270. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.15699/jbibllite.133.2.251. Accessed 17 May 2021.

- ^ Kelly 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Genesis 3:14–15

- ^ Kelly 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Kelly 2006, p. 152.

- ^ Wifall, Walter. "GEN 3:15—A PROTEVANGELIUM?" The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 3, 1974, pp. 361–365. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43713761. Accessed 20 May 2021.

- ^ Gerd Theißen (2009), Erleben und Verhalten der ersten Christen: Eine Psychologie des Urchristentums (in German), Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, p. 251, ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6

- ^ Yvonne S Bonnetain (October 2015), Loki Beweger der Geschichten (in German) (2 ed.), Edition Roter Drache, p. 263, ISBN 978-3-939-459-68-2

- ^ "LUCIFER - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ Gerd Theißen (2009), Erleben und Verhalten der ersten Christen: Eine Psychologie des Urchristentums (in German), Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, p. 251, ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6

- ^ Jerome, "To Eustochium", Letter 22.4, To Eustochium

- ^ Karl R. H. Frick: Satan und die Satanisten I-III. Satanismus und Freimaurerei – ihre Geschichte bis zur Gegenwart. Teil I. Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 978-3-86539-069-1, S. 193.

- ^ The Bible Knowledge Commentary: Old Testament, p. 1283 John F. Walvoord, Walter L. Baker, Roy B. Zuck. 1985 "This 'king' had appeared in the Garden of Eden (v. 13), had been a guardian cherub (v. 14a), had possessed free access ... The best explanation is that Ezekiel was describing Satan who was the true 'king' of Tyre, the one motivating."

- ^ Wikisource:Bible (World English)/Ezekiel § Chapter 28, available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License

- ^ Hector M. Patmore Adam, Satan, and the King of Tyre: The Interpretation of Ezekiel 28:11 –19 in Late Antiquity BRILL, 17.02.2012 isbn 9789004207226 p. 41-53

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael David, eds. (1993). Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford, England: Oxford University. p. 77. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- ^ Florian Theobald Teufel, Tod und Trauer: Der Satan im Johannesevangelium und seine Vorgeschichte Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15.07.2015 isbn 978-3-647-59367-8 p. 35

- ^ Florian Theobald Teufel, Tod und Trauer: Der Satan im Johannesevangelium und seine Vorgeschichte Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15.07.2015 isbn 978-3-647-59367-8 p. 32

- ^ Florian Theobald Teufel, Tod und Trauer: Der Satan im Johannesevangelium und seine Vorgeschichte Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15.07.2015 isbn 978-3-647-59367-8 p. 34

- ^ Florian Theobald Teufel, Tod und Trauer: Der Satan im Johannesevangelium und seine Vorgeschichte Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15.07.2015 isbn 978-3-647-59367-8 pp. 32–35

- ^ Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. 4

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck, Gabriele Boccaccini Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality SBL Press 2016 ISBN 978-0884141181 p. 133

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits (Rev. ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 1-59244-531-4. OCLC 56727898.

- ^ Fahlbusch, E.; Bromiley, G.W. The Encyclopedia of Christianity: P–Sh page 411, ISBN 0-8028-2416-1 (2004)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laurence, Richard (1883). "The Book of Enoch the Prophet".

- ^ Florian Theobald Teufel, Tod und Trauer: Der Satan im Johannesevangelium und seine Vorgeschichte Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15.07.2015 isbn 978-3-647-59367-8 p. 35

- ^ Ra'anan S. Boustan, Annette Yoshiko Reed Heavenly Realms and Earthly Realities in Late Antique Religions Cambridge University Press 2004 ISBN 978-1-139-45398-1 p. 60

- ^ THE DOCTRINE OF SATAN II SATAN IN EXTRA-BIBLICAL APOCALYPTICAL LITERATURE WILLIAM CALDWELL, PH. THE DOCTRINE OF SATAN II SATAN IN EXTRA-BIBLICAL APOCALYPTICAL LITERATURE p. 101

- ^ Florian Theobald Teufel, Tod und Trauer: Der Satan im Johannesevangelium und seine Vorgeschichte Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15.07.2015 isbn 978-3-647-59367-8 p. 37-39

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits (Rev. p. 17 ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 1-59244-531-4. OCLC 56727898.

- ^ Mango, Cyril. "Diabolus Byzantinus." Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 46, 1992, p. 217. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1291654. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kelly 2006, p. 95.

- ^ Robert McQueen Grant Irenaeus of Lyons Psychology Press, 1997 ISBN 9780415118385 p. 130

- ^ Pagels, Elaine. The Social History of Satan, Part II: Satan in the New Testament Gospels. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 62, no. 1, 1994, pp. 17–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1465555. Accessed 27 June 2021.

- ^ Kelly, H. A. (2006). "Satan: A Biography. Vereinigtes Königreich": Cambridge University Press. pp. 82-83

- ^ Jude 1:9

- ^ 1 Peter 5:8

- ^ The Demonology of the New Testament. I Author(s): F. C. Conybeare Source: "The Jewish Quarterly Review", Jul., 1896, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Jul., 1896), p. 578 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1450195

- ^ The Demonology of the New Testament. I Author(s): F. C. Conybeare Source: "The Jewish Quarterly Review", Jul., 1896, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Jul., 1896), p. 583 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1450195

- ^ Hebrews 2:14 (NRSV)

- ^ Kelly, Henry A. Satan: A Biography. Cambridge University Press, 2006. p. 30.

- ^ The Demonology of the New Testament. I Author(s): F. C. Conybeare Source: "The Jewish Quarterly Review", Jul., 1896, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Jul., 1896), p. 579 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1450195

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits (Rev. p. 17 ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 1-59244-531-4. OCLC 56727898.

- ^ Tyneh, C. S. (2003). Orthodox Christianity: Overview and Bibliography. USA: Nova Science Publishers. p.48

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 pp. 201 –202

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits (Rev. p. 17 ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 1-59244-531-4. OCLC 56727898.

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits (Rev. p. 16 ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 1-59244-531-4. OCLC 56727898.

- ^ Yvonne Bonnetain: Loki Beweger der Geschichten. Hrsg.: Edition Roter Drache. 2. Auflage. 2015, ISBN 978-3-939459-68-2, S. 378.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell: Biographie des Teufels: das radikal Böse und die Macht des Guten in der Welt. Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2000, abgerufen am 19. Oktober 2020. (German)

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 11

- ^ B.A. Robinson. "About the Christadelphians: 1848 to now". Individual Christian denominations, from the Amish to The Way.

- ^ Gerd Theißen: Erleben und Verhalten der ersten Christen: Eine Psychologie des Urchristentums. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2009, ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6, p. 251. (German)

- ^ Ramelli, Ilaria L. E. "Origen, Greek Philosophy, and the Birth of the Trinitarian Meaning of 'Hypostasis' " The Harvard Theological Review, vol. 105, no. 3, 2012, pp. 302–350., www.jstor.org/stable/23327679. Accessed 27 Apr. 2021. p.308

- ^ Erkki Koskenniemi, Ida Fröhlich A&C Black, 23.05.2013 ISBN 9780567607386 p. 182

- ^ Panagiōtēs Tzamalikos Origen: Cosmology And Ontology of Time BRILL, 2006 BRILL 2006 ISBN 9789004147287 p. 78

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell: Satan. The Early Christian Tradition. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1987 ISBN 9780801494130, pp. 130 –133.

- ^ Ilaria L.E. Ramelli Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Largo A. Gemelli 1, 20123 Milan, Italy Durham University, UK ilaria.ramelli@unicatt.it Origen in Augustine: A Paradoxical Reception* BRILL p. 301

- ^ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. 39

- ^ Heinz Schreckenberg, Kurt Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity (Van Gorcum, 1992, ISBN 978-9023226536), p. 253

- ^ Jump up to: a b David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. 42

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christoph Horn Augustinus, De civitate dei Oldenbourg Verlag 2010 ISBN 978-3050050409 p. 158

- ^ Babcock, William S. "Augustine on Sin and Moral Agency" The Journal of Religious Ethics, vol. 16, no. 1, 1988, pp. 28–55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40015077. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.

- ^ Neil Forsyth The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth Princeton University Press 1989 ISBN 978-0-691-01474-6 p. 405

- ^ Joad Raymond Milton's Angels: The Early-Modern Imagination OUP Oxford 2010 ISBN 978-0199560509 p. 72

- ^ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. 44

- ^ Couenhoven, Jesse. "Augustine's Rejection of the Free-Will Defence: An Overview of the Late Augustine's Theodicy." Religious Studies, vol. 43, no. 3, 2007, pp. 279–298. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20006375. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.

- ^ TY - JOUR AU - Aiello, Thomas PY - 2010/10/01 SP - 926 EP - 41 T1 - The Man Plague: Disco, the Lucifer Myth, and the Theology of "It's Raining Men" VL - 43 DO - 10.1111/j.1540-5931.2010.00780.x JO - Journal of popular culture ER -

- ^ Burns, J. Patout. "Augustine on the Origin and Progress of Evil" The Journal of Religious Ethics, vol. 16, no. 1, 1988, pp. 9–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40015076. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021. p. 13

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early Christian Tradition Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0801494130 p. 211

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 164

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 165

- ^ Jörn Müller: Willensschwäche in Antike und Mittelalter. Eine Problemgeschichte von Sokrates bis Johannes Duns Scotus (= Ancient and Medieval Philosophy - Series 1. Band 40 German

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 186

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 171

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 167

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 172

- ^ Andrei A. Orlov (2013), Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham (in German), Cambridge University Press, p. 75, ISBN 9781107470996

- ^ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception Brill 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 p. 66

- ^ Gerd Theißen: Erleben und Verhalten der ersten Christen: Eine Psychologie des Urchristentums. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2009, ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6, p. 251 (German)