Iblis

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Iblīs (alternatively Eblīs,[1] Iblees, Eblees or Ibris)[2] is the leader of the devils (Shayāṭīn) in Islam. Regarding the origin and nature of Iblis, there are essentially two different viewpoints:[3][4]

Before Iblis was cast down from heaven, he used to be a highranking angel called Azazil appointed by God to obliterate the original disobedient inhabitants of the earth, so that humans replace them as a more obedient creature. After Iblis objected God's decision to create a successor (khalifa), he was relegated as punishment and subsequently cast down to earth as a devil.

Or, alternately, God created Iblis from the fires beneath the seventh earth. Worshipping God for thousands of years, Iblis ascends to the surface, whereupon, thanks to his pertinacious servanthood, he rises until he reaches the company of angels in the seventh heaven. When God created Adam and ordered the angels to bow down, Iblis, being a jinni created from fire, refuses and disobeys God, leading to his downfall.

In Islamic tradition, Iblis is often identified with Al-Shaytan ("the Devil"), often known by the epithet al-Rajim (Arabic: ٱلرَّجِيْم, lit. 'the Accursed').[5] Shaytan is usually used for Iblis in his role as the tempter, while Iblis is his proper name. Some mystics hold a more ambivalent role for Iblis, depicting him not only as a devil, but also as a true monotheist, while preserving the term shaytan exclusively for evil forces.[6]

Naming and etymology[]

The term Iblīs (Arabic: إِبْلِيس) may have been derived from the Arabic verbal root BLS ب-ل-س (with the broad meaning of "remain in grief")[7] or بَلَسَ (balasa, "he despaired").[8] Furthermore, the name is related to talbis meaning confusion.[9] Another possibility is that it is derived from Ancient Greek διάβολος (diábolos), via a Syriac intermediary,[10] which is also the source of the English word 'devil'.[11]

Yet another possibility relates this name to the bene Elohim (Sons of God), who had been identified with fallen angels in the early centuries, but had been singularized under the name of their leader.[12]

However, there is no general agreement on the root of the term. The name itself could not be found before the Quran in Arab literature,[13] but can be found in , a Christian apocryphal work written in Arabic.[14]

In Islamic traditions, Iblīs is known by many alternative names or titles, such as Abū Murrah (Arabic: أَبُو مُرَّة, "Father of Bitterness") as the name stems from the word "murr" - meaning "bitter", ‘aduww Allāh or ‘aduwallah (Arabic: عُدُوّ الله, "enemy or foe" of God)[15] and Abū Al-Harith (Arabic: أَبُو الْحَارِث, "the father of the plowmen").[16] He is also known by the nickname "Abū Kardūs" (Arabic: أَبُو كَرْدُوس), which may mean "Father who piles up, crams or crowds together".

Theology[]

Theology (Kalām) discusses Iblis' role in the Quran and matters of free-will. Some, especially the Muʿtazila, emphasize free-will and that Iblis freely choose to disobey. Others assert that Iblis was predestined by God to disobey.[17] By that, God shows his entire spectrum of attributes (for example; his wiliness) in the Quran, but also teaches humankind the consequences of sin and disobedience. Al-Damiri reports, most mufassir do not regard disobedience alone to be the reason for Iblis' punishment, but attributing injustice to God by objecting God's order.[18]

According to most scholars, Iblis is a mere creature and thus cannot be the cause or creator of evil in the world; in his function as Satan, he is seen only as a tempter who takes advantage of humanity's weaknesses and self-centeredness and leads them away from God's path.[19][20] The existence of evil has been created by God himself.

Quran[]

Iblis is mentioned 11 times in the Quran by name, nine times related to his refusal against God's command to prostrate himself before Adam. The term Shaytan is more prevalent, although Iblis is sometimes referred to as Shaytan; the terms are not interchangeable. The different fragments of Iblis's story are scattered across the Quran. In the aggregate, the story can be summarised as follows:[21]

When God created Adam, He ordered all the angels to bow before the new creation. All of the angels bowed down, but Iblis refused to do so. He argued that since he was created from fire, he is superior to humans, who were made from clay-mud, and that he should not prostrate himself before Adam.[22] As punishment for his haughtiness, God banished Iblis from heaven and condemned him to hell. Later, Iblis requested the ability to try to mislead Adam and his descendants. God granted his request but also warned him that he would have no power over God's servants.[23]

Affiliation[]

For many Muslim scholars, especially during the classical period, Iblis was regarded as an angel[24][25]: 73 [26] from a tribe called al-jinn, named after heaven. Most scholars of the Salafi school of thought however, agree that Iblis could not have been an angel, consequently regard Iblis as a jinn, a non-heavenly creature different from the angels.[25]

Apart from the Quranic narrative Islamic exegesis offers two different accounts of Iblis's origin: according to one, he was a noble angel, to the other he was an ignoble jinn, who worked his way up to heaven.[27] Some also consider him to be merely the ancestor of Jinn, who was created in heaven, but fell due to his disobedience, as Adam slipped from paradise when he sinned. It might be this moment, Iblis turned into a jinn,[28] but has been an angel created from fire before.[29]

Tabari[30] Ash'ari,[31] Al-Tha`labi,[32] Al-Baydawi[29] and Mahmud al-Alusi[33] are known to regard Iblis as an angel in origin. Tabari argued against the idea that Iblis was a jinn and for an angelic origin of Iblis in his tafsir:

"There is nothing objectionable in that God should have created the categories of His angels from all kinds of things that He had created: He created some of them from light, some of them from fire, and some of them from what He willed apart from that. There is thus nothing in God's omitting to state what He created His angels from, and in His stating what He created Iblis from, which necessarily implies that Iblis is outside of the meaning of [angel], for it is possible that He created a category of His angels, among whom was Iblis, from fire, and even that Iblis was unique in that He created him, and no other angels of His, from the fire of the Samum.

Likewise, he cannot be excluded from being an angel by fact that he had progeny or offspring, because passion and lust, from which the other angels were free, was compounded in him when God willed disobedience in him. As for God's statement that he was < one of the jinn>, it is not to be rejected that everything which hides itself (ijtanna) from the sight is a 'Jinn', as stated before, and Iblis and the angels should then be among them because they hide themselves from the eyes of the sons of Adam."[34]

A contrary opinion was reported from Hasan of Basra, Shi'ite Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq,[35] Fakhr al-Din al-Razi,[33] Ibn Taimiyya and Ibn Kathir, who rejected the idea what Iblis had been once an angel or a unique creature, regarding Iblis to be a jinn instead. Among contemporary scholars this view is also shared by Muhammad Al-Munajjid, who promulgated his view on IslamQA.info and Umar Sulaiman Al-Ashqar, well known for rejecting much of earlier exegtical traditions,[36] in his famous Islamic Creed Series. Ibn Kathir explained Iblis' refusal as a jinn in his tafsir as follows:

"When Allah commanded the angels to prostrate before Adam, Iblis was included in this command. Although Iblis was not an angel, he was trying - and pretending - to imitate the angels' behavior and deeds, and this is why he was also included in the command to the angels to prostrate before Adam. Satan was criticized for defying that command, (. . .)

(So they prostrated themselves except Iblis. He was one of the Jinn;) meaning, his original nature betrayed him. He had been created from smokeless fire, whereas the angels had been created from light, (. . .)

When matters crucial every vessel leaks that which to contains and is betrayed by its true nature. Iblis used to do, what the angels did and resembled them in their devotion and worship, so he was included when they were addressed, but he disobeyed and went what he was told to do. So Allah points out here that he was one of the Jinn, he was created from fire, as He says elsewhere."

As an angel[]

As an angel, Iblis is described as an archangel,[37][38] the leader and teacher of the other angels, and a keeper of heaven. At the same time, he was the closest to the Throne of God. God gave him authority over the lower heavens and the earth. Iblis is also considered the leader of those angels who battled the earthly jinn. Therefore, Iblis and his army drove the jinn to the edge of the world, Mount Qaf. Knowing about the corruption of the former earthen inhabitants, Iblis protested, when he was instructed to prostrate himself before the new earthen inhabitant, that is Adam. He assumed that the angels who praise God's glory day and night are superior in contrast to the mud-made humans and their bodily flaws.[39] He even regarded himself superior in comparison to the other angels, since he was (one of those) created from fire. However, he was degraded by God for his arrogance. But Iblis requested to prove that he is right, therefore God entrusted him as a tempter for humanity as long as his punishment endures, concurrently giving him a chance to redeem himself.[40][41] Since Iblis does not act upon free-will, but as an instrument of God, his abode in hell could be a merely temporary place, until the Judgement Day; and after his assignment as a tempter is over, he might return to God as one of the most cherished angels.[41] His final salvation develops from the idea that Iblis is only an instrument of God's anger, not due to his meritorious personality. Attar compares Iblis's damnation and salvation to the situation of Benjamin, since both were accused to show people a greater meaning, but were finally not condemned.[42]

Furthermore, the transformation of Iblis from angelic into demonic is a reminder of God's capacity to reverse injustice even on an ontological level. It is both a warning and a reminder that the special gifts given by God can also be taken away by Him.[25]: 74

As a Jinn[]

On the other hand, Iblis is commonly placed as one of the Jinn, who lived on earth during the battle of the angels. When the angels took prisoners, Iblis was one of them and carried them to heaven. Since he, unlike the other jinn, was pious, the angels were impressed by his nobility, and Iblis was allowed to join the company of angels and elevated to their rank. However, although he got the outer appearance of an angel, he was still a jinn, in essence, thus he was able to choose when the angels and Iblis were commanded to prostrate themselves before Adam. Iblis, abusing his free will, disobeyed the command of God. Iblis considered himself superior because his physical nature constituted of fire and not of clay.[43] God sentenced Iblis to hell forever, but granted him a favor for his former worship, that is to take revenge on humans by attempting to mislead them until the Day of Judgment. Here, Iblis's damnation is clear and he and his host are the first who enter hell to dwell therein forever,[44] when he is not killed in a battle by the Mahdi, an interpretation especially prevalent among Shia Muslims.[45]

Disputed essence[]

Iblis may either be a fallen angel or a jinni or something entirely unique. This lack of final specification arises from the Quran itself,[46] while Iblis is included into the command addressed to the angels and apparently among them, it is said he was from the jinn in Surah 18:50, whose exact meaning is debated by both Western academics and Islamic scholars.

In academic discourse[]

In most Surahs, it seems to be implied that Iblis is one of the angels. The motif of prostrating angels with one exception among them already appeared in early Christian writings and apocalyptic literature. For this reason, one might assume Iblis was intended to be an angel.[47] argues, that Iblis' identification with the jinn in later Surahs, is a result of the synthesis of Arabian paganism with Judeo-Christian lore. Accordingly, Muhammad would have demonized the jinn in later Surahs, making Iblis a jinni, whereas he had been an angel before.[48] Otherwise, the theory that the essence of angels differs from that of Satan and his hosts, might have originated in the writings of Augustine of Hippo and be introduced by a Christian informant to the early Muslims, and not introduced by Muhammad.[49] Due to the unusual usage of the term jinn in this Surah, some scholars conclude the identification of Iblis with the jinn was merely a temporary one, but not the general opinion[50] or even a later interpolation, added influence by the folkloric perception of jinn as evil creatures but was not part of the original text.[51][52] This idea was supported by the peculiar description of Iblis as created from fire, but not with the same features, the fire from which the jinn are created. Further, Iblis is not described as created from fire, when the Quran identifies Iblis with the jinn.[50] Since the Quran itself does not speak of angels as created from another source than fire, Iblis might also have represented an angel in the sense of Ancient Near Eastern traditions, such as a Seraph.[52] Some scholars objected that the term jinni does not necessarily exclude Iblis from the angels, since it has been suggested that in Pre-Islamic Arabia, the term denoted any type of invisible creature.[53]

But other scholars argue, that Islam nevertheless distinguishes between angels and other kinds of supernatural creatures. Angels would lack the ability to disobey, and taking their constant loyalty as characteristical for the Islamic angels. Further, since the Quran refers to Iblis' progeny, Islamic studies scholar Fritz Meier also insists, that the Islamic Iblis can not be held as an angel, since angels have no progeny by definition.[54] On the other hand, argued that the progeny of Iblis does not correspond with "progeny" in a literal sense, but just refers to the cohorts of Iblis.[55] On another place in the Quran, the progeny of Iblis are said to be created, therefore they can not be literal progeny.[56] Regarding the doctrine of infallible angels, one might argue that the motif of fallen angels is nevertheless not absent within Islamic traditions and therefore, angels are not necessarily always obedient. Although Iblis is described as an infidel (kafir) in the Quran, he did not necessarily sin, since, in the early Islamic period, supernatural creatures were not expected to understand sin or expiate it. Therefore, Iblis would have been created as a rebellious angel.[57]

Among Muslim scholars[]

A question arises about the meaning of the term jinni. The suffix -i might indicate his original relation to jannah, of which he was a guardian and was of a sub-category of "fiery angels". Although angels in Islam are commonly thought to be created from light, angels, or at least the fiercer among them, are also identified as created from fire, as evident from the Miraj literature. Reason for that might be the phonetical similarity between fire (nar) and light (nur). Some scholars argued that fire and light are of the same essence but to a different degree.

On the other hand, scholars arguing that the term jinni refers to jinn, and not a category of angels. They on the other hand need to explain Iblis' stay among the angels. Ibn Kathir stated that Iblis was once an ordinary jinn on earth, but, due to his piety and constant worship, elevated among the angels. He lived there for thousands of years until his non-angelic origin was forgotten and only God remembered Iblis' true identity. When God commanded the angels, Iblis, due to his rank among the angels included, to prostrate himself before Adam, Iblis revealed his true nature. By his refusal his true nature betrayed him, leading to his downfall.[58]

Other scholars, such as Hasan of Basra and Ibn Taymiyyah[citation needed], do not deal with explanations for a reason behind his abode among the angels, by extension of a special narrative. Instead, they argue, Iblis', depicted as the first of the Jinn, and not as one of many Jinn, stay in heaven is self-explanatory, because every creature is created in heaven first. Here, although created in heaven, Iblis is not regarded as an angel, but the equivalent father of the Jinn, compared to what Adam is to humanity. Iblis, as the father of the Jinn, was cast out of heaven due to his sin, just as Adam was banished after his corresponding transgression of God's order not to eat from the Forbidden Tree.

Those scholars, who argue against Iblis' angelic origin also refer to his progeny, since angels do not procreate in Islam. Tabari who defended Iblis' angelic depiction, argues that Iblis did not procreate until he lost his angelic state and became a devil. Therefore, as an angel, Iblis did not procreate and this argument does not apply to Iblis at all. According to some Islamic traditions, Iblis is an asexual entity, just like other angels or a hermaphrodite creature, whose children split from himself, as devils (šayāṭīn) do, but not the Jinn, who have genders just like humans. Yet, there are traditions that report Iblis as having a wife. Al-Suyuti names Iblis' wife Samum. Following Hasan Al Basra's account, they are said to be the primogenitor of the Jinn race.[59]

Another central argument to determine Iblis essence discusses Iblis' ability to disobey. As angels are seen as servants of God, Iblis' should not be able to disobey. This argument had been essential for the advocates who reject the identification with Iblis with one of the angels. As a jinn, however, Iblis could be given the ability to choose to obey or disobey.[60] Scholars who regard Iblis as an angel, agree to some extent with this, but do not see Iblis' refusal as an act of sin in the same way that advocates for "a Jinn nature" do. Many interpret Iblis' disobedience as a sign of predestination. Therefore, Iblis has been created, differing from his fellow angels, from fire, thus God installed a rebellious nature in him, to endow him with the task to seduce humans, comparable as other angels are endowed with tasks corresponding to their nature[61] and created for this purpose from fire differing from the other angels.[61] Thus, Iblis is seen as an instrument of God, not as an entity who freely choose to disobey.[62][63][64] Other scholars gave explanations why an angel should choose to disobey and explain that Iblis was, as the teacher of angels, more knowledgeable than the others.[65][63] Angels might be distinguished by their degree of obedience. Abu Hanifa, founder of the Hanafi schools jurisprudence, is reported as distinguishing between obedient angels, disobedient angels such as Harut and Marut and unbelievers among the angels, like Iblis.[66]

Sufism[]

Sufism developed another perspective on Iblis, integrating him into a greater cosmological scheme. Muhammed and Iblis often became the two true monotheists and God's instrument for punishment and deception. Therefore, some Sufis hold, Iblis refused to bow to Adam because he was devoted to God alone and refused to bow to anyone else. Yet not all Sufis agree with Iblis' redemption.

By weakening the evil in the Satanic figure, dualism is also degraded, that corresponds with the later Sufi cosmology of unity of existence rejecting dualistic tendencies. The belief in dualism or that "evil" is caused by something else than God, even if only by one's own will, is regarded as shirk by some Sufis.[67] For Iblis' preference to be damned to hell rather than prostrating himself before someone else other than the "Beloved" (here referring to God), Iblis also became an example for unrequited love.[68]

As a true Monotheist[]

Among some Sufis, a positive perspective of Iblis' refusal developed, arguing that Iblis was forced to decide between God's command (amr) and will (irāda). Accordingly, Iblis refused to bow to Adam because he was devoted to God alone and refused to bow to anyone else. By weakening the evil in the Satanic figure, dualism is also degraded, that corresponds with the later Sufi cosmology of unity of existence rejecting dualistic tendencies.

A famous narration about an encounter between Moses and Iblis on the slopes of Sinai, told by Mansur al-Hallaj, Ruzbihan Baqli[67] and Abū Ḥāmid Ghazzali, emphasizes the nobility of Iblis. Accordingly, Moses asks Iblis why he refused God's order. Iblis replied that the command was actually a test. Then Moses replied, obviously Iblis was punished by being turned from an angel to a devil. Iblis responds, his form is just temporary and his love towards God remains the same.[69][70]

For Ahmad Ghazali, Iblis was the paragon of lovers in self sacrifice for refusing to bow down to Adam out of pure devotion to God.[71] Ahmad Ghazali's student Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir was among the Sunni Muslim mystics who defended Iblis, asserted that evil was also God's creation, Sheikh Adi argued that if evil existed without the will of God then God would be powerless and a powerless can't be God.[72]

Keeper of Paradise[]

Although in the Quran, Iblis appears only with his fall and intention to mislead God's creation, another role, as the gatekeeper of the divine essence, developed, probably based on the oral reports of the Sahaba. In some interpretations, Iblis is associated with light that misleads people. Hasan of Basra was quoted as saying: "If Iblis were to reveal his light to mankind, they would worship him as a god."[73] Additionally, based on Iblis' role as keeper of heaven and ruler of earth, Ayn al-Quzat Hamadani stated, Iblis represents the "Dark light" that is the earthen world, standing in opposite to the Muhammadan Light that represents the heavens.[74] As such, Iblis would be the treasurer and judge to differentiate between the sinners and the believers. Quzat Hamadani traces back his interpretation to Sahl al-Tustari and who in return claim to derive their opinions from Khidr.[74] Quzat Hamadani relates his interpretation of Iblis' light to the shahada: Accordingly, people whose service for God is just superficial, are trapped within the circle of la ilah (the first part of shahada meaning "there is no God") just worshipping their nafs rather than God. Only those who are worthy to leave this circle can pass Iblis towards the circle of illa Allah the Divine presence.

Rejecting apologetics[]

However, not all Sufis are in agreement with a positive depiction of Iblis. In 's retelling of the encounter between Iblis and Moses. Iblis does not truely offer an excuse for his disobedience. Instead, Iblis' arguements brought forth against Moses are nothing but a sham and subtly deception to make Sufis doubt the authencity of their own spiritual path.[75]

In Rumi's Masnavi Book 2, Iblis wakes up Mu'awiya for prayer. Doubting any good intentions from Satan, Mu'awiya starts arguing with Iblis and asking him for his true intentions. Iblis uses several arguements to proof his own innocence: being a former archangel who would never truly abandon God; being merely a tempter who just brings forth the evil in the sinners, to distinguish them from the believers, but is not evil himself; God's omnipotence and that therefore the ultimate source for Iblis' misguidedness is not Iblis himself. [76][77] Mu'awiya fails to stand against Iblis with reason and seeks refuge in God. Finally, Iblis confesses, he only woke him up, for missing a prayer and causing Mu'awiya to repent, would bring him closer to God, than prayer.[78]

Rumi views Iblis as the manifestation of the great sins of haughtiness and envy. He states: "(Cunning) intelligence is from Iblis, and love from Adam."[79] For Shah Waliullah Dehlawi, Iblis represents the principle of "one-eyed" intellect; he only saw the outward earthly form of Adam, but was blind to the Divine spark hidden in him, using an illicit method of comparison.[80]

Hasan of Basra holds that Iblis was the first who used "analogy", comparing himself to someone else, this causing his sin. Iblis therefore also represents humans' psyche moving towards sin or shows how love can cause envy and anxiety.[81]

Iconography[]

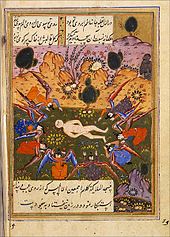

Iblis is perhaps one of the most well-known individual supernatural entities and was depicted in multiple visual representations like the Quran and Manuscripts of Bal‘ami’s ‘Tarjamah-i Tarikh-i Tabari.[82] Iblis was a unique individual, described as both a pious jinn and at times an angel before he fell from God's grace when he refused to bow before the prophet Adam. After this incident, Iblis turned into a shaytan.[83] In visual appearance, Iblis was depicted in On the Monstrous in the Islamic Visual Tradition by Francesca Leoni as a being with a human-like body with flaming eyes, a tail, claws, and large horns on a grossly disproportionate large head.[84]

Illustrations of Iblis in Islamic paintings often depict him black-faced, a feature which would later symbolize any Satanic figure or heretic, and with a black body, to symbolize his corrupted nature. Another common depiction of Iblis shows him wearing a special head covering, clearly different from the traditional Islamic turban. In one painting, however, Iblis wears a traditional Islamic head covering.[85] The turban probably refers to a narration of Iblis' fall: there he wore a turban, then he was sent down from heaven.[86] Many other pictures show and describe Iblis at the moment, when the angels prostrate themselves before Adam. Here, he is usually seen beyond the outcrop, his face transformed with his wings burned, to the envious countenance of a devil.[87] Iblis and his cohorts (div or shayatin) are often portrayed in Turko-Persian art as bangled creatures with flaming eyes, only covered by a short skirt. Similar to European arts, who took traits of pagan deities to depict devils, they depicted such demons often in a similar fashion to that of Hindu-deities.[88]

In literature[]

In the Stories of the Prophets the added biblical serpent appears, although not mentioned in the Quran. Probably known from Gnostic and Jewish oral tradition circulating in the Arabian Peninsula,[89] Iblis tries to enter the abode of Adam, but the angelic guardian keeps him away. Then Iblis invents a plan to trick the guardian. He approaches a peacock and tells him that all creatures will die and the peacock's beauty will perish. But if he gets the fruit of eternity, every creature will last forever. Therefore, the serpent convinces the peacock to slip Iblis into the Garden, by carrying him in his mouth. In another, yet similar narration, Iblis is warded off by Riḍwan's burning sword for 100 years. Then he found the serpent. He says since he was one of the first cherubim, he will one day return to God's grace and promises to show gratitude if the serpent does him a favor.[90] In both narratives, in the Garden, Iblis speaks through the serpent to Adam and Eve, and tricks them into eating from the forbidden tree. Modern Muslims accuse the Yazidis of devil-worship for venerating the peacock.[91]

Iblis is mentioned in the Shahnameh by Ferdowsi. Although the Persian principle of evil is not absent, it is Iblis, instead of Ahriman, who tempts Zahhak to usurp his father.[92][93] Iblis kisses the shoulders of Zahhak, whereupon serpents grew from this spot. This narration roots in ancient Avesta and Iblis can be seen as a substitute for Ahriman in this place.[94]

In Vathek by the English novelist William Beckford, first composed in French (1782), the protagonists enter the underworld, presented as the domain of Iblis. At the end of their journey, they meet Iblis in person, who is described less in the monstrous image of Dante's Satan, but more of a young man, whose regular features are tarnished, his eyes showing both pride and despair and his hair resembling whose of an angel of light.[95]

In Muhammad Iqbal's poetry, Iblis is critical about overstressed obedience, which caused his downfall. But Iblis is not happy about humanity's obedience towards himself either; rather he longs for humans who resist him, so he might eventually prostrate himself before the perfect human, which leads to his salvation.[96]

Egyptian novelist Tawfiq al-Hakim's al-Shahid (1953) describes the necessity of Iblis's evil for the world, telling about a fictional story, Iblis seeking repentance. He consults the Pope and the chief Rabbi. Both reject him and he afterward visits the grand mufti of Al-Azhar Mosque, telling him he wants to embrace Islam. The grand mufti, however, rejects Iblis as well, realizing the necessity of Iblis' evilness. Regarding the absence of Iblis' evil, as causing most of the Quran to be obsolete. After that Iblis goes to heaven to ask Gabriel for intercession. Gabriel too rejects Iblis and explains the necessity for Iblis's curse. Otherwise, God's light could not be seen on earth. Whereupon Iblis descends from heaven shouting out: "I am a martyr!".[97] Al-Hakim's story has been criticized as blasphemous by several Islamic scholars. Salafi scholar Abu Ishaq al-Heweny stated: "I swear by God it would never cross the mind, at all, that this absolute kufr reaches this level, and that it gets published as a novel".[98]

See also[]

- Elbis

- Ghaddar

- Gnosticism

- Mastema

- Melek Taus

- 3 Meqabyan

- Prince of Darkness (Manichaeism)

- Questions of Bartholomew

- Samael

References[]

- ^ Briggs, Constance Victoria (2003). The Encyclopedia of God: An A-Z Guide to Thoughts, Ideas, and Beliefs about God. Newburyport, Massachusetts, the U.S.A.: Hampton Roads Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-612-83225-8.

- ^ Nagawasa, Eiji (March 1992), An Introductory Note on Contemporary Arabic Thought

- ^ Muhammad Mahmoud. "The Creation Story in ‘Sūrat Al-Baqara," with Special Reference to Al-Ṭabarī's Material: An Analysis." Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 26, no. 1/2, 1995, pp. 201–214. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4183374.

- ^ Awn. (2018). Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblīs in Sufi Psychology. With a Foreword by A. Schimmel. Niederlande: Brill. p. 29

- ^ Silverstein, Adam (January 2013). "On the original meaning of the Qur'ānic term al-Shaytān al-Rajīm". Journal of the American Oriental Society.

- ^ Campanini, Massimo (2013). The Qur'an: The Basics. Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1386-6630-6.

- ^ Kazim, Ebrahim (2010). Scientific Commentary of Suratul Faateḥah. New Delhi, India: p. 274. ISBN 978-8-172-21037-3.

- ^ "Iblis".

- ^ Nicholson, Reynold A. (1998). Studies In Islamic Mysticism. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-136-17178-9.

- ^ Basharin, Pavel V. (April 1, 2018). "The Problem of Free Will and Predestination in the Light of Satan's Justification in Early Sufism". English Language Notes. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. 56 (1): 119–138. doi:10.1215/00138282-4337480. S2CID 165366613.

- ^ Wensinck, A. J.; Gardet, L. (24 April 2012). "Iblīs - BrillReference". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Monferrer-Sala, J. P. (2014). One More Time on the Arabized Nominal Form Iblīs. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 112, 55-70. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/store/article/view/9526

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1986). Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-801-49429-1.

- ^ Monferrer-Sala, J. P. (2014). One More Time on the Arabized Nominal Form Iblīs. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 112, 55-70. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/store/article/view/9526

- ^ "Iblis | Meaning, Name, & Significance".

- ^ Zadeh, Travis (2014). "Commanding Demons and Jinn: The Sorcerer in Early Islamic Thought". In Korangy, Alireza; Sheffield, Dan (eds.). No Tapping around Philology: A Festschrift in Honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston Jr.'s 70th Birthday. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 149. ISBN 978-3447102155.

- ^ Lange, Christian, “Devil (Satan)”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 21 August 2021 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_25991> First published online: 2018 First print edition: 9789004356665, 2018, 2018-5

- ^ Sharpe, Elizabeth Marie Into the realm of smokeless fire: (Qur'an 55:14): A critical translation of al-Damiri's article on the jinn from "Hayat al-Hayawan al-Kubra 1953 The University of Arizona download date: 15/03/2020

- ^ Mathewes, Charles (2010). Understanding Religious Ethics. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-405-13351-7.

- ^ Lange, Christian, “Devil (Satan)”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 21 August 2021 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_25991>

- ^ Awn, Peter J. (1983). Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblīs in Sufi Psychology. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. p. 18. ISBN 978-9-0040-6906-0.

- ^ Quran 7:12

- ^ Quran 17:65. ""As for My servants, no authority shalt thou have over them:" Enough is thy Lord for a Disposer of affairs."

- ^ Welch, Alford T. (2008). Studies in Qur'an and Tafsir. Riga, Latvia: Scholars Press. p. 756.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gauvain, Richard (2013). Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God. Abingdon, England, the U.K.: Routledge. pp. 69–74. ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0.

- ^ The Tragic Story of Iblis (Satan) in the Qur'an Mustafa Öztürk 2009, Islamic University of Europa Journal of Islamic Research

- ^ Muhammad Mahmoud. "The Creation Story in ‘Sūrat Al-Baqara," with Special Reference to Al-Ṭabarī's Material: An Analysis." Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 26, no. 1/2, 1995, pp. 201–214. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4183374.

- ^ Hughes, Patrick; Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1995). Dictionary of Islam. New Delhi, India: Asian Educational Services. p. 135. ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vicchio, page 183

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. London, England: A&C Black. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-826-44957-3.

- ^ Palacios, Miguel Asin (2013). Islam and the Divine Comedy. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-134-53643-6.

- ^ "IBLIS". doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Fr. Edmund Teuma THE NATURE OF "IBLI$H IN THE QUR'AN AS INTERPRETED BY THE COMMENTATORS 1980 University of Malta. Faculty of Theology

- ^ https://quran.ksu.edu.sa/tafseer/tabary/sura2-aya34.html

- ^ Ayoub, Mahmoud M. (1984). The Qur'an and Its Interpreters, Volume 1, Band 1. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-791-49546-9.

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi Akhbar al-malik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 13-14

- ^ Muhammed, John (June 1966). "The Day of Resurrection". Islamic Studies. Islamabad, Pakistan: . 5 (2): 136.

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th.; Arnold, Russel; Gibb, Camilla, eds. (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 351. ISBN 978-9-004-08265-6.

- ^ Hampson Stobart, James William (1876). Islam & Its Founder. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University. p. 114.

- ^ Elias, Jamal J. (2014). Key Themes for the Study of Islam. London, England: Oneworld Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-780-74684-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schimmel, Annemarie (1963). Gabriel's Wing: A Study Into the Religious Ideas of Sir Muhammad Iqbal. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 212. ISBN 978-9694160122.

- ^ Awn, Peter J. (1983). Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblīs in Sufi Psychology. Leiden, Germany: Brill Publishers. p. 177 ISBN 978-9004069060.

- ^ Unal, Ali (2008). The Qur'an with Annotated Interpretation in Modern English. Clifton, New Jersey: Tughra Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-597-84144-3.

- ^ Lange, Christian (2015). Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-316-41205-3.

- ^ Idelman Smith, Jane; Yazbeck Haddad, Yvonne (2002). The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-198-03552-7.

- ^ Nünlist, Tobias (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam (in German). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. p. 51. ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages Cornell University Press, 1986 ISBN 9780801494291 p. 56

- ^ Jacques Waardenburg Islam: Historical, Social, and Political Perspectives Walter de Gruyter, 2008 ISBN 978-3-110-20094-2 p. 40

- ^ Jung, L. (1925). Fallen Angels in Jewish, Christian, and Mohammedan Literature. A Study in Comparative Folk-Lore. The Jewish Quarterly Review, 16(1), 45-88. doi:10.2307/1451748

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eichler, Paul Arno, 1889-Die Dschinn, Teufel und Engel in Koran p. 60

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1986). Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-801-49429-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dammen McAuliffe, Jane (2003). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 46. ISBN 978-9004147645.

- ^ El-Zein, Amira (2009). Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0815635147.

- ^ Nünlist, page 54

- ^ Eickmann, Walther (1908). Die Angelologie und Dämonologie des Korans im Vergleich zu der Engel- und Geisterlehre der Heiligen Schrift (in German). New York City: Eger. p. 27.

- ^ Eichler, Paul Arno, 1889- Die Dschinn, Teufel und Engel in Koran p. 59

- ^ Basharin, pages 119–138

- ^ Saed Abdul-Rahman, Muhammad (2013). Tafsir Ibn Kathir Juz' 1 (Part 1): Al-Fatihah 1 to Al-Baqarah 141 2nd Edition. London, England: MSA Publication Limited. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-861-79826-8.

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 103 (German)

- ^ El-Zein, page 46

- ^ Jump up to: a b Awn, page 97

- ^ Schimmel, page 212

- ^ Jump up to: a b Abicht, Ludo (2008). Islam & Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-9-058-67672-6.

- ^ Awn, page 86

- ^ Awn, page 50

- ^ Masood Ali Khan, Shaikh Azhar Iqbal Encyclopaedia of Islam: Religious doctrine of Islam Commonwealth, 2005 ISBN 9788131100523 p. 153

- ^ Jump up to: a b Awn, page 104

- ^ Ghorban Elmi (November 2019). "Ahmad Ghazali's Satan". Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Gramlich, Richard (1998). Der eine Gott: Grundzüge der Mystik des islamischen Monotheismus (in German). Weisbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-447-04025-9.

- ^ Lumbard, Joseph E. B.; al-Ghazali, Ahmad (2016). Remembrance, and the Metaphysics of Love. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-438-45966-0.

- ^ Ghorban Elmi (November 2019). "Ahmad Ghazali's Satan". Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Victoria Arakelova, Garnik S.Asatrian (2014). The Religion of the Peacock angel The Yezidis and their spirit world. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-84465-761-2.

- ^ Ernst, Carl W. (1985). Words of Ecstasy in Sufism. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0873959186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Günther, Sebastian; Lawson, Todd (2016). Roads to Paradise: Eschatology and Concepts of the Hereafter in Islam. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 569. ISBN 978-9-004-33315-4.

- ^ Awn, page 131

- ^ Dévényi, Kinga, and Alexander Fodor, eds. Proceedings of the Colloquium on Paradise and Hell in Islam, Keszthely, 7-14 July 2002. Eotvos Lorand University, Chair for Arabic Studies & Csoma de Koros Society, Section of Islamic Studies, 2008.

- ^ Hodgson, M. G. S. (2009). The Venture of Islam, Volume 2: The Expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods. Vereinigtes Königreich: University of Chicago Press. p. 253

- ^ Hodgson, M. G. S. (2009). The Venture of Islam, Volume 2: The Expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods. Vereinigtes Königreich: University of Chicago Press. p. 253

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1993). The Triumphal Sun: A Study of the Works of Jalaloddin Rumi. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-791-41635-8.

- ^ Allāh al-Dihlawī, Walī (1996). Shāh Walī Allāh of Delhi's Hujjat Allāh Al-bāligha. Albany, New York: Brill Publishers. p. 350. ISBN 978-9-004-10298-9.

- ^ ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, Jalāl (2005). "The Step Into Placelessness". Collected Poetical Works of Rumi. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala Publications. p. 51. ISBN 978-1590302514.

- ^ Leoni, Francesca (2012). On the Monstrous in the Islamic Visual Tradition. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 153–154.

- ^ Leoni, Francesca (2012). On the Monstrous in the Islamic Visual Tradition. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 3.

- ^ Leoni, Francesca (2012). On the Monstrous in the Islamic Visual Tradition. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 5–6.

- ^ Brosh, Na'ama; Milstein, Rachel; Yiśraʼel, Muzeʼon (1991). Biblical stories in Islamic painting. Jerusalem: Israel Museum. p. 27. ASIN B0006F66PC.

- ^ ibn Muḥammad Thaʻlabī, Aḥmad; Brinner, William M. (2002). ʻArāʻis al-majālis fī qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā, or: Lives of the prophets, Band 24. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 69. ISBN 978-9-004-12589-6.

- ^ Melion, Walter; Zell, Michael; Woodall, Joanna (2017). Ut pictura amor: The Reflexive Imagery of Love in Artistic Theory and Practice, 1500-1700. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 240. ISBN 978-9-004-34646-8.

- ^ L. Lewisohn, C. Shackle Attar and the Persian Sufi Tradition: The Art of Spiritual Flight Bloomsbury Publishing, 22.11.2006 ISBN 9781786730183 p. 156-158

- ^ El-Zein, pages 98-99

- ^ Shabaz, Absalom D. (1904). Land of the Lion and the Sun: Personal Experiences, the Nations of Persia-their Manners, Customs, and Their Belief. New Haven, Connecticut: Harvard University. p. 96.

- ^ Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. London, England: I.B. Tauris. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-857-72061-0.

- ^ Warner, Arthur George; Warner, Edmond (2013). The Shahnama of Firdausi, Band 1. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-1136395055.

- ^ Beeman, William O. (2008). The Great Satan Vs. the Mad Mullahs: How the United States and Iran Demonize Each Other. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0226041476.

- ^ Rapp, Stephen H., Jr. (2017). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 978-1317016717.

- ^ Roderick Cavaliero Ottomania: The Romantics and the Myth of the Islamic Orient Bloomsbury Publishing, 02.07.2010 ISBN 9780857715401 p. 66

- ^ Awn, page 9

- ^ Arndt Graf, Schirin Fathi, Ludwig Paul Orientalism and Conspiracy: Politics and Conspiracy Theory in the Islamic World Bloomsbury Publishing 30.11.2010 ISBN 9780857719140 p. 219-221

- ^ Islam Issa Milton in the Arab-Muslim World Taylor & Francis 2016 ISBN 978-1-317-09592-7 page 94

- Angels in Islam

- Demons in Islam

- Fallen angels

- Individual angels

- Jahannam

- Jinn

- Satan

- Devils