Sadducees

Sadducees צְדוּקִים | |

|---|---|

| Historical leaders |

|

| Founded | 167 BCE |

| Dissolved | 73 CE |

| Headquarters | Jerusalem |

| Ideology |

|

| Religion | Hellenistic Judaism |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

The Sadducees (/ˈsædjəsiːz/; Hebrew: צְדוּקִים Ṣĕdûqîm) were a sect or group of Jews who were active in Judea during the Second Temple period, starting from the second century BCE through the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. The Sadducees are often compared to other contemporaneous sects, including the Pharisees and the Essenes.

Josephus associates the sect with the upper social and economic echelon of Judean society.[1] As a whole, they fulfilled various political, social, and religious roles, including maintaining the Temple in Jerusalem. The group became extinct some time after the destruction of Herod's Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Etymology[]

According to Abraham Geiger, the Sadducaic sect of Judaism drew their name from Zadok, the first High Priest of ancient Israel to serve in the First Temple, with the leaders of the sect proposed as the Kohanim (priests, the "sons of Zadok", descendants of Eleazar, son of Aaron).[2] The name Zadok is related to the root צָדַק ṣāḏaq (to be right, just),[3] which could be indicative of their aristocratic status in society in the initial period of their existence.[4]

Flavius Josephus mentions in Antiquities of the Jews that "one Judas, a Gaulonite, of a city whose name was Gamala, who taking with him Sadduc, a Pharisee, became zealous to draw them to a revolt".[5] Paul L. Maier suggests that the sect drew their name from the Sadduc mentioned by Josephus.[6]

History[]

The Second Temple period[]

The Second Temple period is the period between the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 516 BCE and its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE.

Throughout the Second Temple period, Jerusalem saw several shifts in rule. Alexander's conquest of the Mediterranean world brought an end to Persian control of Jerusalem (539–334/333 BCE) and ushered in the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic period, which extended from 334/333 BCE to 63 BCE, is known today for the spread of Hellenistic influence.

After the death of Alexander in 323 BCE, his generals divided the empire among themselves and for the next 30 years, they fought for control of the empire. Judea was first controlled by the Ptolemies of Egypt (r. 301–200 BCE) and later by the Seleucids of Syria (r. 200–167). King Antiochus Epiphanes of Syria, a Seleucid, disrupted whatever peace there had been in Judea when he desecrated the temple in Jerusalem and forced Jews to violate the Torah. Most prominent of the rebel groups were the Maccabees, led by Mattathias the Hasmonean and his son Judah the Maccabee. Though the Maccabees rebelled against the Seleucids in 164 BCE, Seleucid rule did not end for another 20 years. The Maccabean (a.k.a. Hasmonean) rule lasted until 63 BCE, when the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem.

Thus began the Roman period of Judea, leading to the creation of the province of Roman Judea in 6 CE and extending into the 7th century CE, well beyond the end of the Second Temple period. Cooperation between the Romans and the Jews was strongest during the reigns of Herod and his grandson, Herod Agrippa I. However, the Romans moved power out of the hands of vassal kings and into the hands of Roman administrators, beginning with the Census of Quirinius in 6 CE. The First Jewish–Roman War broke out in 66 CE. After a few years of conflict, the Romans retook Jerusalem and destroyed the temple, bringing an end to the Second Temple period in 70 CE.[7]

Role of the Temple[]

During the Persian period, the Temple became more than the center of worship in Judea after its reconstruction in 516 BCE; it served as the center of society. It makes sense, then, that priests held important positions as official leaders outside of the Temple. The democratizing forces of the Hellenistic period lessened and shifted the focus of Judaism away from the Temple and in the 3rd century BCE, a scribal class began to emerge. New organizations and "social elites," according to Shaye Cohen, appeared.[citation needed]

It was also during this time that the high priesthood, the members of which often identified as Sadducees, was developing a reputation for corruption. Questions about the legitimacy of the Second Temple and its Sadducaic leadership freely circulated within Judean society. Sects began to form during the Maccabean reign (see Jewish sectarianism below).[8] The Temple in Jerusalem was the formal center of political and governmental leadership in ancient Israel, although its power was often contested and disputed by fringe groups.

After the Temple destruction[]

After the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE, the Sadducees appear only in a few references in the Talmud and in some Christian texts.[9] In the beginnings of Karaism, the followers of Anan ben David were called "Sadducees" and set a claim of the former being a historical continuity from the latter.[citation needed]

The Sadducee concept of the mortality of the soul is reflected on by Uriel Acosta, who mentions them in his writings. Acosta was referred to as a Sadducee in Karl Gutzkow's play The Sadducees in Amsterdam (1834).[citation needed]

Role of the Sadducees[]

Religious[]

The religious responsibilities of the Sadducees included the maintenance of the Temple in Jerusalem. Their high social status was reinforced by their priestly responsibilities, as mandated in the Torah. The priests were responsible for performing sacrifices at the Temple, the primary method of worship in ancient Israel. This included presiding over sacrifices during the three festivals of pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Their religious beliefs and social status were mutually reinforcing, as the priesthood often represented the highest class in Judean society. However, Sadducees and the priests were not completely synonymous. Cohen points out that "not all priests, high priests, and aristocrats were Sadducees; many were Pharisees, and many were not members of any group at all."[10]

Political[]

The Sadducees oversaw many formal affairs of the state.[11] Members of the Sadducees:

- Administered the state domestically

- Represented the state internationally

- Participated in the Sanhedrin, and often encountered the Pharisees there.

- Collected taxes. These also came in the form of international tribute from Jews in the Diaspora.

- Equipped and led the army

- Regulated relations with the Roman Empire

- Mediated domestic grievances.

Beliefs[]

General[]

The Sadducees rejected the Oral Torah as proposed by the Pharisees. Rather, they saw the Written Torah as the sole source of divine authority.[12] The written law, in its depiction of the priesthood, corroborated the power and enforced the hegemony of the Sadducees in Judean society.

According to Josephus, the Sadducees believed that:[13]

- There is no fate.

- God does not commit evil.[14]

- Man has free will; "man has the free choice of good or evil".

- The soul is not immortal; there is no afterlife.[15]

- There are no rewards or penalties after death.

The Sadducees did not believe in resurrection of the dead, but believed (contrary to the claim of Josephus) in the traditional Jewish concept of Sheol for those who had died.[16]

According to the Christian Acts of the Apostles:

- The Sadducees did not believe in resurrection, whereas the Pharisees did. In Acts, Paul chose this point of division to gain the protection of the Pharisees.[17]

- The Sadducees also rejected the notion of spirits or angels, whereas the Pharisees acknowledged them.[18]

The Sadducees are said to have favored Sirach.[citation needed]

Disputes with the Pharisees[]

- According to the Sadducees, spilt water became impure through its pouring. Pharisees denied that this is sufficient grounds for ṭumah "impurity" (Hebrew: טומאה).[19] Many Pharisee–Sadducee disputes revolved around issues of ṭumah and ṭaharah (Hebrew: טָהֳרָה, ritual purity).

- According to the Jewish laws of inheritance, the property of a deceased man is inherited by his sons, but if the man had only daughters, his property is inherited by his daughters upon his death (Numbers 27:8). The Sadducees, however, in defiance of Jewish tradition, whenever dividing the inheritance among the relatives of the deceased, such as when the deceased left no issue, would perfunctorily seek for familial ties, regardless and irrespective of gender, so that the near of kin to the deceased and who inherits his property could, hypothetically, be his paternal aunt. The Sadducees would justify their practice by A fortiori, an inference from minor to major premise, saying: "If the daughter of his son's son can inherit him (i.e. such as when her father left no male issue), is it not then fitting that his own daughter inherit him?!" (i.e. who is more closely related to him than his great granddaughter).[20] Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai tore down their argument, saying that the only reason the daughter was empowered to inherit her father was because her father left no male issue. However, a man's daughter – where there are sons, has no power to inherit her father's estate. Moreover, a deceased man who leaves no issue has always a distant male relative, unto whom is given his estate. The Sadducees eventually agreed with the Pharisaic teaching. The vindication of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai and the Pharisees over the Sadducees gave rise to this date being held in honor in the Scroll of Fasting.[21][22][23]

- The Sadducees demanded that the master pay for damages caused by his slave. The Pharisees imposed no such obligation, as the slave may intentionally cause damage in order to see the liability for it brought on his master.[19]

- The Pharisees posited that false witnesses should be executed if the verdict is pronounced on the basis of their testimony—even if not yet actually carried out. The Sadducees argued that false witnesses should be executed only if the death penalty has already been carried out on the falsely accused.[24]

Jewish sectarianism[]

The Jewish community of the Second Temple period is often defined by its sectarian and fragmented attributes. Josephus, in Antiquities, contextualizes the Sadducees as opposed to the Pharisees and the Essenes. The Sadducees are also notably distinguishable from the growing Jesus movement, which later evolved into Christianity. These groups differed in their beliefs, social statuses, and sacred texts. Though the Sadducees produced no primary works themselves, their attributes can be derived from other contemporaneous texts, namely, the New Testament, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and later, the Mishnah and Talmud. Overall, the Sadducees represented an aristocratic, wealthy, and traditional elite within the hierarchy.

Opposition to the Essenes[]

The Dead Sea Scrolls, which are often attributed to the Essenes, suggest clashing ideologies and social positions between the Essenes and the Sadducees. In fact, some scholars suggest that the Essenes began as a group of renegade Zadokites, which would indicate that the group itself had priestly, and thus Sadducaic origins. Within the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Sadducees are often referred to as Manasseh. The scrolls suggest that the Sadducees (Manasseh) and the Pharisees (Ephraim) became religious communities that were distinct from the Essenes, the true Judah. Clashes between the Essenes and the Sadducees are depicted in the Pesher on Nahum, which states "They [Manasseh] are the wicked ones ... whose reign over Israel will be brought down ... his wives, his children, and his infant will go into captivity. His warriors and his honored ones [will perish] by the sword."[25] The reference to the Sadducees as those who reign over Israel corroborates their aristocratic status as opposed to the more fringe group of Essenes. Furthermore, it suggests that the Essenes challenged the authenticity of the rule of the Sadducees, blaming the downfall of ancient Israel and the siege of Jerusalem on their impiety. The Dead Sea Scrolls brand the Sadducaic elite as those who broke the covenant with God in their rule of the Judean state, and thus became targets of divine revenge.

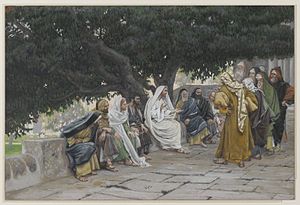

Opposition to the early Christian church[]

The New Testament, specifically the books of Mark and Matthew, describe anecdotes which hint at hostility between the early Christians and the Sadducaic establishment. These disputes manifest themselves on both theological and social levels. Mark describes how the Sadducees challenged Jesus' belief in the resurrection of the dead. Jesus subsequently defends his belief in resurrection against Sadducaic resistance, stating, "and as for the dead being raised, have you not read in the book of Moses, in the story about the bush, how God said to him "I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob?" He is God not of the dead, but of the living; you are quite wrong."[26] According to Matthew's Gospel, Jesus asserts that the Sadducees were wrong because they knew "neither the scriptures nor the power of God".[27][28] Jesus challenges the reliability of Sadducaic interpretation of biblical doctrine, the authority of which enforces the power of the Sadducaic priesthood. The Sadducees address the issue of resurrection through the lens of marriage, which "hinted at their real agenda: the protection of property rights through patriarchal marriage that perpetuated the male lineage."[29] Furthermore, Matthew records John the Baptist calling the Pharisees and Sadducees a "brood of vipers".[30] The New Testament thus constructs the identity of Christianity in opposition to the Sadducees.

Opposition to the Pharisees[]

The Pharisees and the Sadducees are historically seen as antitheses of one another.[citation needed] Josephus, the author of the most extensive historical account of the Second Temple Period, gives a lengthy account of Jewish sectarianism in both The Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews. In Antiquities, he describes "the Pharisees have delivered to the people a great many observances by succession from their fathers, which are not written in the law of Moses, and for that reason it is that the Sadducees reject them and say that we are to esteem those observance to be obligatory which are in the written word, but are not to observe what are derived from the tradition of our forefathers."[12] The Sadducees rejected the Pharisaic use of the Oral Torah to enforce their claims to power, citing the Written Torah as the sole manifestation of divinity.

The rabbis, who are traditionally seen as the descendants of the Pharisees, describe the similarities and differences between the two sects in Mishnah Yadaim. The Mishnah explains that the Sadducees state, "So too, regarding the Holy Scriptures, their impurity is according to (our) love for them. But the books of Homer, which are not beloved, do not defile the hands."[31] A passage from the book of Acts suggests that both Pharisees and Sadducees collaborated in the Sanhedrin, the high Jewish court.[32]

References[]

- ^ "...while the Sadducees are able to persuade none but the rich, and have not the populace obsequious to them, but the Pharisees have the multitude on their side."Josephus. AJ. Translated by Whiston, William. 13.10.6..

- ^ Abraham Geiger, Urschrift, pp. 20–

- ^ צָדוֹק

- ^ Newman, p. 76

- ^ Josephus. AJ. Translated by Whiston, William. 18.1.1..

- ^ Josephus, Flavius (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Academic. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-82542924-8.

- ^ Cohen, 1–5, 15–16

- ^ Cohen, 153–154

- ^ See: Philippe Bobichon, "Autorités religieuses juives et ‘sectes’ juives dans l’œuvre de Justin Martyr", Revue des Études Augustiniennes 48/1 (2002), pp. 3-22 (online).

- ^ Cohen 155

- ^ Wellhausen, 45

- ^ Jump up to: a b Josephus. AJ. 13.10.6..

- ^ Josephus. The Jewish War. Translated by Thackeray, Henry St. John. 2.162.

- ^ Note: Thackeray's translation of The Jewish War, cited above, says that the Sadducees "remove God beyond, not merely the commission, but the very sight, of evil". However, Whiston's translation (hosted at Perseus) renders this passage: "God is not concerned in our doing or not doing what is evil".

- ^ Josephus, Titus Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews 18 §1.2.

- ^ Manson, T.W.: Sadducee and Pharisee - The Origin and Significance of the Names John Rylands Library, p. 154.

- ^ Acts 23:6–9

- ^ Acts 23:8

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mishnah Yadaim 4:7

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 21b)

- ^ Rashbam in the Babylonian Talmud (Baba Bathra 115b–116a); Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 8:1 [21b–22a)

- ^ Segal of Kraków, Avraham, ed. (1857). Megillat Taanit (in Hebrew). Cracow (?): Hemed. p. 14-16. OCLC 233298491.

- ^ Derenbourg, J. (1970). The Oracle of the Land of Israel: Chronicles of the Country from the time of Cyrus to Hadrian, based on the Sages of the Mishnah and the Talmud (משא ארץ ישראל : דברי ימי הארץ מימי כרש ועד אדריאנוס על פי חכמי המשנה והתלמוד) (in Hebrew). 1–2. Translated by Menahem Mendel Braunstein. Jerusalem: Kedem. pp. 115–117. OCLC 233219980.

- ^ Mishnah Makot 1.6

- ^ Pesher on Nahum in Eshol, 40

- ^ Mark 12:27

- ^ Matthew 22:29

- ^ Pulpit Commentary on Matthew 22, accessed 14 February 2017

- ^ Commentary, New Oxford Annotated Bible

- ^ Matthew 3:7

- ^ Mishnah Yadaim 4:6–8

- ^ Acts 23:6

Primary[]

- Coogan, Michael, ed. (2007). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-528882-7.

- Flavius, Titus Josephus (1998). Tenney, Merrill (ed.). Complete Works. Nelson Reference. ISBN 978-0-7852-1427-4.

- Vermes, Geza, ed. (2004). The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Harmondsworth, ENG: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044952-5.

Secondary[]

- Cohen, Shaye (2006). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22743-2.

- Eshel, Hanan (2008). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. City: Wm.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6285-3.

- Johnson, Paul (1988). A History of the Jews. San Francisco: Perennial Library. ISBN 978-0-06-091533-9.

- Newman, Hillel (2006). Proximity to Power and Jewish Sectarian Groups of the Ancient Period: a Review of Lifestyle, Values, and Halakha in the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and Qumran. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14699-0.

- Stemberger, Günter (1995). Jewish Contemporaries of Jesus. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2624-2.

- Vermes, Geza (2003). Jesus in His Jewish Context. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-3623-4.

- Wellhausen, Julius (2001). The Pharisees and the Sadducees. Macon: Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-729-2.

- Mishnah Yadayim 4:6–8, The Pharisee–Sadducee Debate, COJS.

External links[]

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Ancient Jewish Greek history

- Jews and Judaism in the Roman Empire

- Jewish religious movements

- Judaism-related controversies