Alice Munro

Alice Munro | |

|---|---|

| Born | Alice Ann Laidlaw 10 July 1931 Wingham, Ontario, Canada |

| Occupation | Short-story writer |

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | The University of Western Ontario[1] |

| Genre | Short stories, Realism, Southern Ontario Gothic |

| Notable awards | Governor General's Award (1968, 1978, 1986) Giller Prize (1998, 2004) Man Booker International Prize (2009) Nobel Prize in Literature (2013) |

| Spouse | James Munro

(m. 1951; div. 1972)Gerald Fremlin

(m. 1976; died 2013) |

| Children | 4 |

Alice Ann Munro (/mʌnˈroʊ/, née Laidlaw /ˈleɪdlɔː/; born 10 July 1931) is a Canadian short story writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013. Munro's work has been described as revolutionizing the architecture of short stories, especially in its tendency to move forward and backward in time.[2] Her stories have been said to "embed more than announce, reveal more than parade."[3]

Munro's fiction is most often set in her native Huron County in southwestern Ontario.[4] Her stories explore human complexities in an uncomplicated prose style.[5] Munro's writing has established her as "one of our greatest contemporary writers of fiction", or, as Cynthia Ozick put it, "our Chekhov."[6] Munro has received many literary accolades, including the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature for her work as "master of the contemporary short story",[7] and the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work. She is also a three-time winner of Canada's Governor General's Award for fiction, and received the Writers' Trust of Canada's 1996 Marian Engel Award and the 2004 Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize for Runaway.[7][8][9][10]

Early life and education[]

Munro was born Alice Ann Laidlaw in Wingham, Ontario. Her father, Robert Eric Laidlaw, was a fox and mink farmer,[11] and later turned to turkey farming.[12] Her mother, Anne Clarke Laidlaw (née Chamney), was a schoolteacher. She is of Irish and Scottish descent; her father is a descendant of James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd.[13]

Munro began writing as a teenager, publishing her first story, "The Dimensions of a Shadow", in 1950 while studying English and journalism at the University of Western Ontario on a two-year scholarship.[14][15] During this period she worked as a waitress, a tobacco picker, and a library clerk. In 1951, she left the university, where she had been majoring in English since 1949, to marry fellow student James Munro. They moved to Dundarave, West Vancouver, for James's job in a department store. In 1963, the couple moved to Victoria, where they opened Munro's Books, which still operates.

Career[]

Munro's highly acclaimed first collection of stories, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), won the Governor General's Award, then Canada's highest literary prize.[16] That success was followed by Lives of Girls and Women (1971), a collection of interlinked stories. In 1978, Munro's collection of interlinked stories Who Do You Think You Are? was published (titled The Beggar Maid: Stories of Flo and Rose in the United States). This book earned Munro a second Governor General's Literary Award.[17] From 1979 to 1982, she toured Australia, China and Scandinavia for public appearances and readings. In 1980 Munro held the position of writer in residence at both the University of British Columbia and the University of Queensland.

From the 1980s to 2012, Munro published a short-story collection at least once every four years. First versions of Munro's stories have appeared in journals such as The Atlantic Monthly, Grand Street, Harper's Magazine, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Narrative Magazine, and The Paris Review. Her collections have been translated into 13 languages.[1] On 10 October 2013, Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, cited as a "master of the contemporary short story".[7][8][18] She is the first Canadian and the 13th woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.[19]

Munro is noted for her longtime association with editor and publisher Douglas Gibson.[20] When Gibson left Macmillan of Canada in 1986 to launch the Douglas Gibson Books imprint at McClelland and Stewart, Munro returned the advance Macmillan had already paid her for The Progress of Love so that she could follow Gibson to the new company.[21] Munro and Gibson have retained their professional association ever since; when Gibson published his memoirs in 2011, Munro wrote the introduction, and to this day Gibson often makes public appearances on Munro's behalf when her health prevents her from appearing personally.[22]

Almost 20 of Munro's works have been made available for free on the web, in most cases only the first versions.[23] From the period before 2003, 16 stories have been included in Munro's own compilations more than twice, with two of her works scoring four republications: "Carried Away" and "Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage".[24]

Film adaptations of Munro's short stories have included Martha, Ruth and Edie (1988), Edge of Madness (2002), Away from Her (2006), Hateship, Loveship (2013) and Julieta (2016).

Writing[]

Many of Munro's stories are set in Huron County, Ontario. Her strong regional focus is one of her fiction's features. Another is an omniscient narrator who serves to make sense of the world. Many compare Munro's small-town settings to writers from the rural American South. As in the works of William Faulkner and Flannery O'Connor, Munro's characters often confront deep-rooted customs and traditions, but her characters' reactions are generally less intense than their Southern counterparts'. Her male characters tend to capture the essence of the everyman, while her female characters are more complex. Much of Munro's work exemplifies the Southern Ontario Gothic literary genre.[25]

Munro's work is often compared with the great short-story writers. In her stories, as in Chekhov's, plot is secondary and "little happens". As in Chekhov, Garan Holcombe says, "All is based on the epiphanic moment, the sudden enlightenment, the concise, subtle, revelatory detail." Munro's work deals with "love and work, and the failings of both. She shares Chekhov's obsession with time and our much-lamented inability to delay or prevent its relentless movement forward."[26]

A frequent theme of her work, particularly in her early stories, has been the dilemmas of a girl coming of age and coming to terms with her family and her small hometown. In recent work such as Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage (2001) and Runaway (2004) she has shifted her focus to the travails of middle age, women alone, and the elderly. Her characters often experience a revelation that sheds light on, and gives meaning to, an event.

Munro's prose reveals the ambiguities of life: "ironic and serious at the same time," "mottoes of godliness and honor and flaming bigotry," "special, useless knowledge," "tones of shrill and happy outrage," "the bad taste, the heartlessness, the joy of it." Her style juxtaposes the fantastic and the ordinary, with each undercutting the other in ways that simply and effortlessly evoke life.[27] Robert Thacker wrote:

Munro's writing creates ... an empathetic union among readers, critics most apparent among them. We are drawn to her writing by its verisimilitude – not of mimesis, so-called and ... 'realism' – but rather the feeling of being itself ... of just being a human being."[28]

Many critics have written that Munro's stories often have the emotional and literary depth of novels. Some have asked whether Munro actually writes short stories or novels. Alex Keegan, writing in Eclectica, gave a simple answer: "Who cares? In most Munro stories there is as much as in many novels."[29]

Research on Munro's work has been undertaken since the early 1970s, with the first PhD thesis published in 1972.[30] The first book-length volume collecting the papers presented at the University of Waterloo first conference on her work was published in 1984, The Art of Alice Munro: Saying the Unsayable.[31] In 2003/2004, the journal Open Letter. Canadian quarterly review of writing and sources published 14 contributions on Munro's work. In autumn 2010, the Journal of the Short Story in English (JSSE)/Les cahiers de la nouvelle dedicated a special issue to Munro, and in May 2012 an issue of the journal Narrative focussed on a single story by Munro, "Passion" (2004), with an introduction, summary of the story, and five analytical essays.[32]

Creating new versions[]

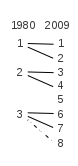

Munro publishes variant versions of her stories, sometimes within a short span of time. Her stories "Save the Reaper" and "Passion" came out in two different versions in the same year, in 1998 and 2004 respectively. Two other stories were republished in a variant versions about 30 years apart, "Home" (1974/2006/2014) and "Wood" (1980/2009).[33]

In 2006 Ann Close and Lisa Dickler Awano reported that Munro had not wanted to reread the galleys of Runaway (2004): "No, because I'll rewrite the stories." In their symposium contribution An Appreciation of Alice Munro they say that of her story "Powers", for example, Munro did eight versions in all.[34]

Awano writes that "Wood" is a good example of how Munro, "a tireless self-editor",[35] rewrites and revises a story, in this case returning to it for a second publication nearly 30 years later, revising characterizations, themes and perspectives, as well as rhythmic syllables, a conjunction or a punctuation mark. The characters change, too. Inferring from the perspective they take on things, they are middle-age in 1980, and in 2009 they are older. Awano perceives a heightened lyricism brought about not least by the poetic precision of the revision Munro undertakes.[35] The 2009 version comprises eight sections to the 1980 version's three, and has a new ending. Awano writes that Munro literally "refinishes" the first take on the story with an ambiguity characteristic of Munro's endings, and that Munro reimagines her stories throughout her work a variety of ways.[35]

Several stories were republished with considerable variation as to which content goes into which section. This can be seen, for example, in "Home", "The Progress of Love", "What Do You Want to Know For?", "The Children Stay", "Save the Reaper", "The Bear Came Over the Mountain", "Passion", "The View From Castle Rock", "Wenlock Edge", and "Deep-Holes".

Personal life[]

Munro married James Munro in 1951. Their daughters Sheila, Catherine, and Jenny were born in 1953, 1955, and 1957 respectively; Catherine died the day of her birth due to the lack of functioning kidneys.[36]

In 1963, the Munros moved to Victoria, where they opened Munro's Books, a popular bookstore still in business. In 1966, their daughter Andrea was born. Alice and James Munro divorced in 1972.

Munro returned to Ontario to become writer in residence at the University of Western Ontario, and in 1976 received an honorary LLD from the institution. In 1976, she married Gerald Fremlin, a cartographer and geographer she met in her university days.[14] The couple moved to a farm outside Clinton, Ontario, and later to a house in Clinton, where Fremlin died on 17 April 2013, aged 88.[37] Munro and Fremlin also owned a home in Comox, British Columbia.[1]

At a Toronto appearance in October 2009, Munro indicated that she had received treatment for cancer and for a heart condition requiring coronary-artery bypass surgery.[38]

In 2002, Sheila Munro published a childhood memoir, Lives of Mothers and Daughters: Growing Up with Alice Munro.[39]

Works[]

Original short-story collections[]

- Dance of the Happy Shades – 1968 (winner of the 1968 Governor General's Award for Fiction)

- Lives of Girls and Women – 1971 (winner of the Canadian Bookseller's Award[40])

- Something I've Been Meaning to Tell You – 1974

- Who Do You Think You Are? – 1978 (winner of the 1978 Governor General's Award for Fiction; also published as The Beggar Maid; short-listed for the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1980[40])

- The Moons of Jupiter – 1982 (nominated for a Governor General's Award)

- The Progress of Love – 1986 (winner of the 1986 Governor General's Award for Fiction)

- Friend of My Youth – 1990 (winner of the Trillium Book Award)

- Open Secrets – 1994 (nominated for a Governor General's Award)

- The Love of a Good Woman – 1998 (winner of the 1998 Giller Prize and the 1998 National Book Critics Circle Award)

- Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage – 2001 (republished as Away from Her)

- Runaway – 2004 (winner of the Giller Prize and Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize)

- The View from Castle Rock – 2006

- Too Much Happiness – 2009

- Dear Life – 2012

Short-story compilations[]

- Selected Stories (later retitled Selected Stories 1968–1994 and A Wilderness Station: Selected Stories, 1968–1994) – 1996

- No Love Lost – 2003

- Vintage Munro – 2004

- Alice Munro's Best: A Selection of Stories – Toronto 2006 / Carried Away: A Selection of Stories – New York 2006; both 17 stories (spanning 1977–2004) with an introduction by Margaret Atwood

- New Selected Stories – 2011

- Lying Under the Apple Tree. New Selected Stories, 434 pages, 15 stories,[41] c Alice Munro 2011, Vintage, London 2014, paperback

- Family Furnishings: Selected Stories 1995–2014 – 2014

Selected awards and honours[]

Awards[]

- Governor General's Literary Award for English language fiction (1968, 1978, 1986)

- Canadian Booksellers Award for Lives of Girls and women (1971)

- Shortlisted for the annual (UK) Booker Prize for Fiction (1980) for The Beggar Maid

- The Writers' Trust of Canada's Marian Engel Award (1986) for her body of work [10]

- Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize (2004) for Runaway[42]

- Trillium Book Award for Friend of My Youth (1991), The Love of a Good Woman (1999) and Dear Life (2013)[43]

- WH Smith Literary Award (1995, UK) for Open Secrets

- Lannan Literary Award for Fiction (1995)

- PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in Short Fiction (1997)

- National Book Critics Circle Award (1998, U.S.) For The Love of a Good Woman

- Giller Prize (1998 and 2004)

- Rea Award for the Short Story (2001) given to a living American or Canadian author.

- Libris Award

- Edward MacDowell Medal for outstanding contribution to the arts by the MacDowell Colony (2006).[44]

- O. Henry Award for continuing achievement in short fiction in the U.S. for "Passion" (2006), "What Do You Want To Know For" (2008) and "Corrie" (2012)

- Man Booker International Prize (2009, UK)[45]

- Canada-Australia Literary Prize

- Commonwealth Writers Prize Regional Award for Canada and the Caribbean.

- Nobel Prize in Literature (2013) as a "master of the contemporary short story".[7]

Honours[]

- 1992: Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1993: Royal Society of Canada's Lorne Pierce Medal

- 2005: Medal of Honor for Literature from the U.S. National Arts Club

- 2010: Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters[46]

- 2014: Silver coin released by the Royal Canadian Mint in honour of Munro's Nobel Prize win [47]

- 2015: Postage stamp released by Canada Post in honour of Munro's Nobel Prize win [48]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Preface. Dance of the Happy Shades. Alice Munro. First Vintage contemporaries Edition, August 1998. ISBN 0-679-78151-X Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc. New York City.

- ^ Alice Munro Wins Nobel Prize in Literature, by Julie Bosmans, The New York Times, 10 October 2013

- ^ W. H. New. "Literature in English". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Marchand, P. (29 August 2009). "Open Book: Philip Marchand on Too Much Happiness, by Alice Munro". The National Post. Retrieved 5 September 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Meyer, M. "Alice Munro". Meyer Literature. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ^ Merkin, Daphne (24 October 2004). "Northern Exposures". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2013 – Press Release" (PDF). 10 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bosman, Julie (10 October 2013). "Alice Munro Wins Nobel Prize in Literature". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Alice Munro wins Man Booker International prize". The Guardian. 27 May 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Past Writers' Trust Engel/Findley Award Winners". Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Jeanne McCulloch, Mona Simpson "Alice Munro, The Art of Fiction No. 137", The Paris Review No. 131, Summer 1994

- ^ Gaunce, Julia, Suzette Mayr, Don LePan, Marjorie Mather, and Bryanne Miller, eds. "Alice Munro." The Broadview Anthology of Short Fiction. 2nd ed. Buffalo, NY: Broadview Press, 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Catherine (10 October 2013). "For Alice Munro, small is beautiful" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jason Winders (10 October 2013). "Alice Munro, LLD'76, wins 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature". Western News. The University of Western Ontario.

- ^ "Canada's Alice Munro, 'master' of short stories, wins Nobel Prize in literature". CNN. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "Past GG Winners 1968". canadacouncil.ca. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Past GG Winners 1978". canadacouncil.ca. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Alice Munro wins Nobel Prize for Literature". BBC News. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Saul Bellow, the 1976 laureate, was born in Canada, but he moved to the United States at age nine and became a US citizen at twenty-six.

- ^ Panofsky, Ruth (2012). The Literary Legacy of the Macmillan Company of Canada: Making Books and Mapping Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9877-1.

- ^ "Munro follows publisher Gibson from Macmillan". Toronto Star, 30 April 1986.

- ^ "Alice Munro unlikely to come out of retirement following Nobel win". CTV News, 11 October 2013.

- ^ Which of the stories have free Web versions.

- ^ For further details, see List of short stories by Alice Munro.

- ^ Susanne Becker, Gothic Forms of Feminine Fictions. Manchester University Press, 1999.

- ^ Holcombe, Garan (2005). "Alice Munro". Contemporary Writers. London: British Arts Council. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ Hoy, Helen (1980). "Dull, Simple, Amazing and Unfathomable: Paradox and Double Vision In Alice Munro's Fiction". Studies in Canadian Literature. University of New Brunswick. 5 (1). Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ Thacker, Robert (1998) Review of Some other reality: Alice Munro's Something I've been Meaning to Tell You, by Louis K. MacKendrick. Journal of Canadian Studies, Summer 1998.

- ^ Keegan, Alex (August–September 1998). "Munro: The Short Answer". Eclectica. 2 (5). Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ J.R. (Tim) Struthers, Some Highly Subversive Activities: A Brief Polemic and a Checklist of Works on Alice Munro, in: Studies in Canadian Literature, Volume 06, Number 1 (1981).

- ^ The Art of Alice Munro: Saying the Unsayable (1984) was edited by Judith Miller. Source: Héliane Ventura, Introduction to Special issue: The Short Stories of Alice Munro, Journal of the Short Story in English / Les Cahiers de la nouvelle, No. 55, Autumn 2010.

- ^ Journal of the Short Story in English (JSSE)/Les cahiers de la nouvelle special issue

- ^ For details please see List of short stories by Alice Munro

- ^ An Appreciation of Alice Munro, by Ann Close and Lisa Dickler Awano, Compiler and Editor. In: The Virginia Quarterly Review. VQR Symposium on Alice Munro. Summer 2006, pp. 102–105.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lisa Dickler Awano, Kindling The Creative Fire: Alice Munro's Two Versions of "Wood", New Haven Review, 30 May 2012.

- ^ Thacker, Robert (2014). "Alice Munro – Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "Gerald Fremlin (obituary)". Clinton News-Record. April 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ The Canadian Press (22 October 2009). "Alice Munro reveals cancer fight". CBC News. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Harrison, Kathryn (16 June 2002). "Go Ask Alice". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Besner, Neil K., "Introducing Alice Munro's Lives of Girls and Women: A Reader's Guide" (Toronto: ECW Press), 1990

- ^ See List of short stories by Alice Munro

- ^ "Past Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize Winners". Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Trillium Book Award Winners". omdc.on.ca. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Medal Day History". MacDowell Colony. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ The Booker Prize Foundation "Alice Munro wins 2009 Man Booker International Prize." Archived 2 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ARCHIVED – Canada Gazette – GOVERNMENT HOUSE". Gazette.gc.ca. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ "Mint releases silver coin to honour Alice Munro's Nobel win". The Globe and Mail. 24 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Alice Munro". 10 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

Further reading[]

- Atwood, Margaret et al. "Appreciations of Alice Munro." Virginia Quarterly Review 82.3 (Summer 2006): 91–107. Interviews with various authors (Margaret Atwood, Russell Banks, Michael Cunningham, Charles McGrath, Daniel Menaker and others) presented in first-person essay format

- Awano, Lisa Dickler. "Kindling The Creative Fire: Alice Munro's Two Versions of 'Wood.'" New Haven Review (30 May 2012). Examining overall themes in Alice Munro's fiction through a study of her two versions of "Wood."

- Awano, Lisa Dickler. "Alice Munro's Too Much Happiness." Virginia Quarterly Review (22 October 2010). Long-form book review of Too Much Happiness in the context of Alice Munro's canon.

- Besner, Neil Kalman. Introducing Alice Munro's Lives of Girls and Women: a reader's guide. (Toronto: ECW Press, 1990)

- Blodgett, E. D. Alice Munro. (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1988)

- Buchholtz, Miroslawa (ed.). Alice Munro. Understanding, Adapting, Teaching (Springer International Publishing, 2016)

- Carrington, Ildikó de Papp. Controlling the Uncontrollable: the fiction of Alice Munro. (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1989)

- Carscallen, James. The Other Country: patterns in the writing of Alice Munro. (Toronto: ECW Press, 1993)

- Cox, Alisa. Alice Munro. (Tavistock: Northcote House, 2004)

- Dahlie, Hallvard. Alice Munro and Her Works. (Toronto: ECW Press, 1984)

- Davey, Frank. 'Class, Family Furnishings, and Munro's Early Stories.' In Ventura and Conde. 79–88.

- de Papp Carrington, Ildiko."What's in a Title?: Alice Munro's 'Carried Away.'" Studies in Short Fiction. 20.4 (Fall 1993): 555.

- Dolnick, Ben. "A Beginner's Guide to Alice Munro" The Millions (5 July 2012)

- Elliott, Gayle. "A Different Track: Feminist meta-narrative in Alice Munro's 'Friend of My Youth.'" Journal of Modern Literature. 20.1 (Summer 1996): 75.

- Fowler, Rowena. "The Art of Alice Munro: The Beggar Maid and Lives of Girls and Women." Critique. 25.4 (Summer 1984): 189.

- Garson, Marjorie. "Alice Munro and Charlotte Bronte." University of Toronto Quarterly 69.4 (Fall 2000): 783.

- Genoways, Ted. "Ordinary Outsiders." Virginia Quarterly Review 82.3 (Summer 2006): 80–81.

- Gibson, Douglas. Stories About Storytellers: Publishing Alice Munro, Robertson Davies, Alistair MacLeod, Pierre Trudeau, and Others. (ECW Press, 2011.) Excerpt.

- Gittings, Christopher E.. "Constructing a Scots-Canadian Ground: Family history and cultural translation in Alice Munro." Studies in Short Fiction 34.1 (Winter 1997): 27

- Hebel, Ajay. The Tumble of Reason: Alice Munro's discourse of absence. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994)

- Hiscock, Andrew. "Longing for a Human Climate: Alice Munro's 'Friend of My Youth' and the culture of loss." Journal of Commonwealth Literature 32.2 (1997): 18.

- Hooper, Brad The Fiction of Alice Munro: An Appreciation (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2008), ISBN 978-0-275-99121-0

- Houston, Pam. "A Hopeful Sign: The making of metonymic meaning in Munro's 'Meneseteung.'" Kenyon Review 14.4 (Fall 1992): 79.

- Howells, Coral Ann. Alice Munro. (New York: Manchester University Press, 1998), ISBN 978-0-7190-4558-5

- Hoy, H. "'Dull, Simple, Amazing and Unfathomable': Paradox and Double Vision In Alice Munro's Fiction." Studies in Canadian Literature/Études en littérature canadienne, Volume 5.1. (1980).

- Lecercle, Jean-Jacques. 'Alice Munro's Two Secrets.' In Ventura and Conde. 25–37.

- Levene, Mark. "It Was About Vanishing: A Glimpse of Alice Munro's Stories." University of Toronto Quarterly 68.4 (Fall 1999): 841.

- Lorre-Johnston,Christine, and Eleonora Rao, eds. Space and Place in Alice Munro's Fiction: "A Book with Maps in It." Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2018.ISBN 978-1-64014-020-2[1].

- Lynch, Gerald. "No Honey, I'm Home." Canadian Literature 160 (Spring 1999): 73.

- MacKendrick, Louis King. Some Other Reality: Alice Munro's Something I've Been Meaning to Tell You. (Toronto: ECW Press, 1993)

- Martin, W.R. Alice Munro: paradox and parallel. (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1987)

- Mazur, Carol and Moulder, Cathy. Alice Munro: An Annotated Bibliography of Works and Criticism. (Toronto: Scarecrow Press, 2007) ISBN 978-0-8108-5924-1

- McCaig, JoAnn. Reading In: Alice Munro's archives. (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2002)

- Miller, Judith, ed. The Art of Alice Munro: saying the unsayable: papers from the Waterloo conference. (Waterloo: Waterloo Press, 1984)

- Munro, Sheila. Lives of Mother and Daughters: growing up with Alice Munro. (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2001)

- Murray, Jennifer. Reading Alice Munro with Jacques Lacan. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016)

- Pfaus, B. Alice Munro. (Ottawa: Golden Dog Press, 1984.)

- Rasporich, Beverly Jean. Dance of the Sexes: art and gender in the fiction of Alice Munro. (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1990)

- Redekop, Magdalene. Mothers and Other Clowns: the stories of Alice Munro. (New York: Routledge, 1992)

- Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. Alice Munro: a double life. (Toronto: ECW Press, 1992.)

- Simpson, Mona. A Quiet Genius The Atlantic. (December 2001)

- Smythe, Karen E. Figuring Grief: Gallant, Munro and the poetics of elegy. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992)

- Somacarrera, Pilar. A Spanish Passion for the Canadian Short Story: Reader Responses to Alice Munro's Fiction in Web 2.0 Open Access, in: Made in Canada, Read in Spain: Essays on the Translation and Circulation of English-Canadian Literature Open Access, edited by Pilar Somacarrera, de Gruyter, Berlin 2013, p. 129–144, ISBN 978-83-7656-017-5

- Steele, Apollonia and Tener, Jean F., editors. The Alice Munro Papers: Second Accession. (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1987)

- Tausky, Thomas E. Biocritical Essay. The University of Calgary Library Special Collections (1986)

- Thacker, Robert. Alice Munro: writing her lives: a biography. (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2005)

- Thacker, Robert. Ed. The Rest of the Story: critical essays on Alice Munro. (Toronto: ECW Press, 1999)

- Ventura, Héliane, and Mary Condé, eds. Alice Munro. Open Letter 11:9 (Fall-Winter 2003-4). ISSN 0048-1939. Proceedings of the Alice Munro conference L'écriture du secret/Writing Secrets, Université d'Orléans, 2003.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alice Munro |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alice Munro. |

- Works by or about Alice Munro in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- List of Works

- Alice Munro at IMDb

- Alice Munro collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- "Alice Munro, The Art of Fiction No. 137", The Paris Review No. 131, Summer 1994

- W. H. New. "Literature in English".

- Alice Munro at the British Council Writers Directory

- Stories by Alice Munro accessible online

- Alice Munro's papers (fonds) held at the University of Calgary

- How To Tell If You Are in an Alice Munro Story, 8 December 2014

- Unwin, Stewart (2017). "Alice Munro bibliography".

- Alice Munro on Nobelprize.org

with a pre-recorded video conversation with the Laureate Alice Munro: In Her Own Words

with a pre-recorded video conversation with the Laureate Alice Munro: In Her Own Words

- 1931 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Canadian short story writers

- 20th-century Canadian women writers

- 21st-century Canadian short story writers

- 21st-century Canadian women writers

- Canadian Nobel laureates

- Canadian people of Irish descent

- Canadian people of Scottish descent

- Canadian women short story writers

- Chevaliers of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Governor General's Award-winning fiction writers

- Man Booker International Prize winners

- Members of the Order of Ontario

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- PEN/Malamud Award winners

- People from Wingham, Ontario

- The New Yorker people

- University of Western Ontario alumni

- Women Nobel laureates

- Writers from Ontario