Southern United States

Coordinates: 33°N 88°W / 33°N 88°W

Southern United States

Southern States, American South, the South | |

|---|---|

Region | |

Regional definitions vary from source to source. This map reflects the Southern United States as defined by the Census Bureau.[1] | |

| Subregions |

|

| Country | United States |

| States | Alabama Arkansas Delaware Florida Georgia Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Mississippi North Carolina Oklahoma South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia West Virginia |

| Federal district | District of Columbia |

| Population (2020[2]) | |

| • Total | 126,266,107 |

| Demonym(s) | Southerner, Southron (historically) |

| Languages | show

Creole languages show

English variants show

Louisiana FrenchIndigenous Languages Spanish |

The Southern United States, also referred to as the Southern States, American South or simply the South, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States. It is between the Atlantic Ocean and the Western United States, with the Midwestern United States and Northeastern United States to its north and the Gulf of Mexico and Mexico to its south. It also has major portions that are part of the Eastern United States.

Historically, the South was defined as all states south of the 18th century Mason–Dixon line, the Ohio River, and 36°30′ parallel.[3] Within the South are different subregions, such as the Southeast, South Central, Upper South and Deep South. Since an influx of Northern transplants in the mid-to-late 20th century, Maryland, Delaware, Northern Virginia, and Washington, D.C. have become more culturally, economically, and politically aligned in certain aspects with that of the Northeast, and are often identified as part of the Mid-Atlantic subregion or Northeast by many residents, businesses, public institutions, and private organizations.[4] However, the United States Census Bureau continues to define them as in the South with regard to Census regions.[5] Due to cultural variations across the region, some scholars have proposed definitions of the South that do not coincide neatly with state boundaries.[6][7] The South does not precisely correspond to the entire geographic south of the United States, but primarily includes the south-central and southeastern states. For example, California which is geographically in the southwestern part of the country, is not considered part, while the geographically southeastern Georgia is.[8][9][10]

The South, being home to some of the most racially diverse areas in the United States, is known for its culture and history, having developed its own customs, fashion, architecture, musical styles, and cuisines, which have distinguished it in many ways from other areas of the United States. During 1860 and 1861, eleven Southern states would secede from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America. Following the American Civil War, these states were subsequently added back to the Union. Sociological research indicates that Southern collective identity stems from political, historical, demographic, and cultural distinctiveness from the rest of the United States. Ethnic groups in the South are the most diverse among American regions, and includes strong European (especially English, Scots-Irish, Scottish, Irish, French, and Spanish), African, and Native American components.[11]

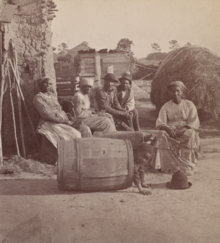

Aspects of the early historical and cultural development of the South were influenced by the institution of slave labor, mainly within the Deep South and coastal plain areas, during the early 1600s to mid-1800s. This includes the presence of a large proportion of African Americans within the population, support for the doctrine of states' rights, and legacy of racism magnified by the Civil War and Reconstruction era (1865–1877). Following effects included thousands of lynchings (mostly from 1880 to 1930), segregated system of separate schools and public facilities established from Jim Crow laws that remained until the 1960s, and the widespread use of poll taxes and other methods to deny black and poor people the ability to vote or hold office until the 1960s. Scholars have characterized pockets of the Southern United States as being "authoritarian enclaves" from Reconstruction until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[12][13][14][15] Since the 1970s, due to improved racial relations, a growing economic base and job opportunities in the region, the South has seen increases of African Americans moving from other U.S. regions in a New Great Migration.[16]

When looked at broadly, studies have shown that Southerners tend to be more conservative than most non-Southerners, although liberalism is also predominant in many areas throughout the region.[17][18] The South is usually reliably Republican in most states, however both the Republican and Democratic Party are competitive in a handful of Southern states, known as swing states. The region contains almost all of the Bible Belt, an area of high Protestant church attendance, especially evangelical churches such as the Southern Baptist Convention. Historically, the South relied heavily on agriculture for its main economic base, and was highly rural until after World War II. Since the 1940s, the region has become more economically diversified and urban, helping attract many national and international migrants. Today, it is among the fastest-growing areas in the United States, with Houston being the region's largest city.[19]

Geography[]

The South is a diverse meteorological region with numerous climatic zones, including temperate, sub-tropical, tropical and arid – though the South generally has a reputation as hot and humid, with long summers and short, mild winters. Most of the South – except for the areas of higher elevations and areas near the western, southern and some northern fringes – fall in the humid subtropical climate zone. Crops grow readily in the South due to its climate consistently providing growing seasons of at least six months before the first frost. Another common environment occurs within the bayous and swamplands of the Gulf Coast, especially in Louisiana and in Texas.

The question of how to define the boundaries and subregions in the South has been the focus of research and debate for centuries.[20][21] As defined by the United States Census Bureau,[1] the Southern region of the United States includes sixteen states. As of 2010, an estimated 114,555,744 people, or thirty seven percent of all U.S. residents, lived in the South, the nation's most populous region.[22] The Census Bureau defined three smaller divisions:

- The South Atlantic States: Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia.

- The East South Central States: Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee.

- The West South Central States: Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas.

The Council of State Governments, an organization for communication and coordination between states, includes in its South regional office the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia.[23]

Other terms related to the South include:

- The Old South: Can mean either southern states that were among the Thirteen Colonies (Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina) or all southern slave states before 1860 (which also includes Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas).[24]

- The New South: All southern states following the American Civil War, post Reconstruction era.[25]

- Southeastern United States: Usually includes the Carolinas, the Virginias, Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida.[26]

- Southern Appalachia: Mainly refers to areas situated in the southern Appalachian Mountains, namely Eastern Kentucky, East Tennessee, Western North Carolina, Western Maryland, West Virginia, Southwest Virginia, North Georgia and Northwestern South Carolina.[27]

- Upper South: Usually includes Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina and on rare occasions Missouri, Maryland and Delaware.[28] When combined with the southern Appalachian Mountains, its sometimes referred to as "Greater Appalachia" following Ulster Protestant migrations to the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries.[29]

- Deep South: Various definitions, usually includes Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina.[30]

- Border States: Includes Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia. These were states on the outer rim of the Confederacy that did not secede from the U.S. in the 1860s, but had large numbers of residents who joined both the Union and Confederate armed forces. Kentucky and Missouri had Confederate governments-in-exile and were represented in the Confederate Congress and by stars on the Confederate battle flag. West Virginia formed in 1863, after the western region of Virginia broke away to protest the Old Dominion's joining of the Confederacy, but residents of the new state were about evenly divided on supporting the Union or Confederacy.[31]

- Dixie: Nickname applied to Southern U.S. region, various definitions include certain areas more than others, but most commonly associated with the eleven former Confederate States.

- Solid South: Electoral voting bloc largely controlled by the Democratic Party from 1877 to 1964, largely resulting from disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction era in the late 19th century. Disfranchisement effectively denied most of the black and sometimes poor white population from voting or holding public office during this time period.[32]

- Gulf Coast: Includes Gulf coasts of Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas and Alabama.

- Tidewater: Low-lying Atlantic coastal plain regions of Maryland, Delaware, Virginia and North Carolina.

- Mid-South: Various definitions, includes states within the Census Bureau of the East and West South Central United States.[33] In another informal definition, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi are included, with adjoining areas of other states.[34][35][36][37]

Historically, the South was defined as all states south of the 18th century Mason–Dixon line, the Ohio River, and 36°30′ parallel.[38] Newer definitions of the South today are harder to define, due to cultural and sub-regional differences throughout the region, however definitions usually refer to states that are in the southeastern and south central geographic region of the United States.[39]

Although not included in the Census definition, two U.S. territories located southeast of Florida (Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) are sometimes included as part of the Southern United States. The Federal Aviation Administration includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands as part of the South,[40] as does the Agricultural Research Service and the U.S. National Park Service.[41][42]

History[]

Native American culture[]

The first well-dated evidence of human occupation in the south United States occurs around 9500 BC with the appearance of the earliest documented Americans, who are now referred to as Paleo-Indians.[43] Paleoindians were hunter-gatherers that roamed in bands and frequently hunted megafauna. Several cultural stages, such as Archaic (ca. 8000–1000 BC) and the Woodland (ca. 1000 BC – AD 1000), preceded what the Europeans found at the end of the 15th century – the Mississippian culture.[43]

The Mississippian culture was a complex, mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Southeastern United States from approximately 800 AD to 1500 AD. Natives had elaborate and lengthy trading routes connecting their main residential and ceremonial centers extending through the river valleys and from the East Coast to the Great Lakes.[43] Some noted explorers who encountered and described the Mississippian culture, by then in decline, included Pánfilo de Narváez (1528), Hernando de Soto (1540), and Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (1699).

Native American descendants of the mound-builders include Alabama, Apalachee, Caddo, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Guale, Hitchiti, Houma, and Seminole peoples, all of whom still reside in the South.

Other peoples whose ancestral links to the Mississippian culture are less clear but were clearly in the region before the European incursion include the Catawba and the Powhatan.

European colonization[]

European immigration caused a die-off of Native Americans, whose immune systems could not protect them from the diseases the Europeans unwittingly introduced.[44]

The predominant culture of the original Southern states was English. In the 17th century, most voluntary immigrants were of English origin, and settled chiefly along the eastern coast but had pushed as far inland as the Appalachian Mountains by the 18th century. The majority of early English settlers were indentured servants, who gained freedom after working off their passage. The wealthier men who paid their way received land grants known as headrights, to encourage settlement.[45]

The Spanish and French established settlements in Florida, Texas, and Louisiana. The Spanish settled Florida in the 16th century, reaching a peak in the late 17th century, but the population was small because the Spaniards were relatively uninterested in agriculture, and Florida had no mineral resources.

In the British colonies, immigration began in 1607 and continued until the outbreak of the Revolution in 1775. Settlers cleared land, built houses and outbuildings, and on their own farms. The Southern rich owned large plantations that dominated export agriculture and used slaves. Many were involved in the labor-intensive cultivation of tobacco, the first cash crop of Virginia. Tobacco exhausted the soil quickly, requiring that farmers regularly clear new fields. They used old fields as pasture, and for crops such as corn wheat, or allowed them to grow into woodlots.[46]

In the mid-to-late-18th century, large groups of Ulster Scots (later called the Scotch-Irish) and people from the Anglo-Scottish border region immigrated and settled in the back country of Appalachia and the Piedmont. They were the largest group of non-English immigrants from the British Isles before the American Revolution.[47] In the 1980 Census, 34% of Southerners reported that they were of English ancestry; English was the largest reported European ancestry in every Southern state by a large margin.[48]

The early colonists engaged in warfare, trade, and cultural exchanges. Those living in the backcountry were more likely to encounter Creek Indians, Cherokee, and Choctaws and other regional native groups.

The oldest university in the South, the College of William & Mary, was founded in 1693 in Virginia; it pioneered in the teaching of political economy and educated future U.S. Presidents Jefferson, Monroe and Tyler, all from Virginia. Indeed, the entire region dominated politics in the First Party System era: for example, four of the first five Presidents – Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe – were from Virginia. The two oldest public universities are also in the South: the University of North Carolina (1789) and the University of Georgia (1785).

American Revolution[]

During the American Revolutionary War, the Southern colonies helped embrace the Patriot cause. Virginia would provide leaders such as commander-in-chief George Washington, and the author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson.

In 1780 and 1781, the British largely halted reconquest of the northern states, and concentrated on the south, where they were told there was a large Loyalist population ready to leap to arms once the royal forces arrived. The British took control of Savannah and Charleston, capturing a large American army in the process, and set up a network of bases inland. Although there were Loyalists within the Southern colonies,[49] they were concentrated in larger coastal cities, and were not great enough in number to overcome the revolutionaries. The British forces at the Battle of Monck's Corner and the Battle of Lenud's Ferry consisted entirely of Loyalists with the exception of the commanding officer (Banastre Tarleton).[50] Both white and black Loyalists fought for the British at the Battle of Kemp's Landing in Virginia.[51][52] Led by Nathanael Greene and other generals, the Americans engaged in Fabian tactics designed to wear down the British invasion force, and to neutralize its strong points one by one. There were numerous battles large and small, with each side claiming some victories.

By 1781, however, British General Cornwallis moved north to Virginia, where an approaching army forced him to fortify and await rescue by the British Navy. The British Navy did arrive, but so did a stronger French fleet, and Cornwallis was trapped. American and French armies, led by George Washington, forced Cornwallis to surrender his entire army in Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781, effectively winning the North American part of the war.[53]

The Revolution provided a shock to slavery in the South and other regions of the new country. Thousands of slaves took advantage of wartime disruption to find their own freedom, catalyzed by the British Governor Dunmore of Virginia's promise of freedom for service. Many others were removed by Loyalist owners and became slaves elsewhere in the British Empire. Between 1770 and 1790, there was a sharp decline in the percentage of blacks – from 61% to 44% in South Carolina and from 45% to 36% in Georgia.[54] In addition, some slaveholders were inspired to free their slaves after the Revolution. They were moved by the principles of the Revolution, along with Quaker and Methodist preachers who worked to encourage slaveholders to free their slaves. Planters such as George Washington often freed slaves by their wills. In the Upper South, more than 10% of all blacks were free by 1810, a significant expansion from pre-war proportions of less than 1% free.[55]

Antebellum years[]

Cotton became dominant in the lower South after 1800. After the invention of the cotton gin, short staple cotton could be grown more widely. This led to an explosion of cotton cultivation, especially in the frontier uplands of Georgia, Alabama and other parts of the Deep South, as well as riverfront areas of the Mississippi Delta. Migrants poured into those areas in the early decades of the 19th century, when county population figures rose and fell as swells of people kept moving west. The expansion of cotton cultivation required more slave labor, and the institution became even more deeply an integral part of the South's economy.[56]

With the opening up of frontier lands after the government forced most Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi, there was a major migration of both whites and blacks to those territories. From the 1820s through the 1850s, more than one million enslaved Africans were transported to the Deep South in forced migration, two-thirds of them by slave traders and the others by masters who moved there. Planters in the Upper South sold slaves excess to their needs as they shifted from tobacco to mixed agriculture. Many enslaved families were broken up, as planters preferred mostly strong males for field work.[57]

Two major political issues that festered in the first half of the 19th century caused political alignment along sectional lines, strengthened the identities of North and South as distinct regions with certain strongly opposed interests, and fed the arguments over states' rights that culminated in secession and the Civil War. One of these issues concerned the protective tariffs enacted to assist the growth of the manufacturing sector, primarily in the North. In 1832, in resistance to federal legislation increasing tariffs, South Carolina passed an ordinance of nullification, a procedure in which a state would, in effect, repeal a Federal law. Soon a naval flotilla was sent to Charleston harbor, and the threat of landing ground troops was used to compel the collection of tariffs. A compromise was reached by which the tariffs would be gradually reduced, but the underlying argument over states' rights continued to escalate in the following decades.

The second issue concerned slavery, primarily the question of whether slavery would be permitted in newly admitted states. The issue was initially finessed by political compromises designed to balance the number of "free" and "slave" states. The issue resurfaced in more virulent form, however, around the time of the Mexican–American War, which raised the stakes by adding new territories primarily on the Southern side of the imaginary geographic divide. Congress opposed allowing slavery in these territories.

Before the Civil War, the number of immigrants arriving at Southern ports began to increase, although the North continued to receive the most immigrants. Huguenots were among the first settlers in Charleston, along with the largest number of Orthodox Jews outside of New York City.[citation needed] Numerous Irish immigrants settled in New Orleans, establishing a distinct ethnic enclave now known as the Irish Channel. Germans also went to New Orleans and its environs, resulting in a large area north of the city (along the Mississippi) becoming known as the German Coast. Still greater numbers immigrated to Texas (especially after 1848), where many bought land and were farmers. Many more German immigrants arrived in Texas after the Civil War, where they created the brewing industry in Houston and elsewhere, became grocers in numerous cities, and also established wide areas of farming.

By 1840, New Orleans was the wealthiest city in the country and the third largest in population. The success of the city was based on the growth of international trade associated with products being shipped to and from the interior of the country down the Mississippi River. New Orleans also had the largest slave market in the country, as traders brought slaves by ship and overland to sell to planters across the Deep South. The city was a cosmopolitan port with a variety of jobs that attracted more immigrants than other areas of the South.[58] Because of lack of investment, however, construction of railroads to span the region lagged behind the North. People relied most heavily on river traffic for getting their crops to market and for transportation.

Civil War[]

By 1856, the South had lost control of Congress, and was no longer able to silence calls for an end to slavery – which came mostly from the more populated, free states of the North. The Republican Party, founded in 1854, pledged to stop the spread of slavery beyond those states where it already existed. After Abraham Lincoln was elected the first Republican president in 1860, seven cotton states declared their secession and formed the Confederate States of America before Lincoln was inaugurated. The United States government, both outgoing and incoming, refused to recognize the Confederacy, and when the new Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered his troops to open fire on Fort Sumter in April 1861, war broke out. Only the state of Kentucky attempted to remain neutral, and it could only do so briefly. When Lincoln called for troops to suppress what he referred to as "combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary" judicial or martial means,[60] four more states decided to secede and join the Confederacy (which then moved its capital to Richmond, Virginia). Although the Confederacy had large supplies of captured munitions and many volunteers, it was slower than the Union in dealing with the border states. While the Upland border states of Kentucky, Missouri, West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware, as well as the District of Columbia, continued to permit slavery during the Civil War, they remained with the Union. By March 1862, the Union largely controlled all the border state areas, had shut down all commercial traffic from all Confederate ports, had prevented European recognition of the Confederate government, and was poised to seize New Orleans.

In the four years of war 1861–65 the South was the primary battleground, with all but two of the major battles taking place on Southern soil. Union forces led numerous campaigns into the western Confederacy, controlling the border states in 1861, the Tennessee River, the Cumberland River and New Orleans in 1862, and the Mississippi River in 1863. In the East, however, the Confederate Army under Robert E. Lee beat off attack after attack in its defense of their capital at Richmond. But when Lee tried to move north, he was repulsed (and nearly captured) at Sharpsburg (1862) and Gettysburg (1863).

The Confederacy had the resources for a short war, but was unable to finance or supply a longer war. It reversed the traditional low-tariff policy of the South by imposing a new 15% tax on all imports from the Union. The Union blockade stopped most commerce from entering the South, and smugglers avoided the tax, so the Confederate tariff produced too little revenue to finance the war. Inflated currency was the solution, but that created distrust of the Richmond government. Because of low investment in railroads, the Southern transportation system depended primarily on river and coastal traffic by boat; both were shut down by the Union Navy. The small railroad system virtually collapsed, so that by 1864 internal travel was so difficult that the Confederate economy was crippled.

The Confederate cause was hopeless by the time Atlanta fell and William T. Sherman marched through Georgia in late 1864, but the rebels fought on until Lee's army surrendered in April 1865. Once the Confederate forces surrendered, the region moved into the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877), in a partially successful attempt to rebuild the destroyed region and grant civil rights to freed slaves.

Southerners who were against the Confederate cause during the Civil War were known as Southern Unionists. They were also known as Union Loyalists or Lincoln's Loyalists. Within the eleven Confederate states, states such as Tennessee (especially East Tennessee), Virginia (which included West Virginia at the time), and North Carolina were home to the largest populations of Unionists. Many areas of Southern Appalachia harbored pro-Union sentiment as well. As many as 100,000 men living in states under Confederate control would serve in the Union Army or pro-Union guerilla groups. Although Southern Unionists came from all classes, most differed socially, culturally, and economically from the regions dominant pre-war planter class.[61]

The South suffered more than the North overall, as the Union strategy of attrition warfare meant that Lee could not replace his casualties, and the total war waged by Sherman, Sheridan and other Union armies devastated the infrastructure and caused widespread poverty and distress. The Confederacy suffered military losses of 95,000 men killed in action and 165,000 who died of disease, for a total of 260,000,[62] out of a total white Southern population at the time of around 5.5 million.[63] Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white males aged 13 to 43 died in the war, including 6% in the North and about 18% in the South.[64] Northern military casualties exceeded Southern casualties in absolute numbers, but were two-thirds smaller in terms of proportion of the population affected.

Reconstruction and Jim Crow era[]

After the Civil War, the South was devastated in terms of infrastructure and economy. Because of states' reluctance to grant voting rights to freedmen, Congress instituted Reconstruction governments. It established military districts and governors to rule over the South until new governments could be established. Many white Southerners who had actively supported the Confederacy were temporarily disenfranchised. Rebuilding was difficult as people grappled with the effects of a new labor economy of a free market in the midst of a widespread agricultural depression. In addition, limited infrastructure the South had was mostly destroyed by the war. At the same time, the North was rapidly industrializing. To avoid the social effects of the war, most of the Southern states initially passed black codes. During Reconstruction, these were mostly legally nullified by federal law and anti-Confederate legislatures, which existed for a short time during Reconstruction.[65]

There were thousands of people on the move, as African Americans tried to reunite families separated by slave sales, and sometimes migrated for better opportunities in towns or other states. Other freed people moved from plantation areas to cities or towns for a chance to get different jobs. At the same time, whites returned from refuges to reclaim plantations or town dwellings. In some areas, many whites returned to the land to farm for a while. Some freedpeople left the South altogether for states such as Ohio and Indiana, and later, Kansas. Thousands of others joined the migration to new opportunities in the Mississippi and Arkansas Delta bottomlands, and Texas.

With passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States (which outlawed slavery), the 14th Amendment (which granted full U.S. citizenship to African Americans) and the 15th amendment (which extended the right to vote to African American males), African Americans in the South were made free citizens and were given the right to vote. Under Federal protection, white and black Republicans formed constitutional conventions and state governments. Among their accomplishments were creating the first public education systems in Southern states, and providing for welfare through orphanages, hospitals and similar institutions.

Northerners came south to participate in politics and business. Some were representatives of the Freedmen's Bureau and other agencies of Reconstruction; some were humanitarians with the intent to help black people. Some were adventurers who hoped to benefit themselves by questionable methods. They were all condemned with the pejorative term of carpetbagger. Some Southerners would also take advantage of the disrupted environment and made money off various schemes, including bonds and financing for railroads.[66]

Secret vigilante organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan – an organization sworn to perpetuate white supremacy – had arisen quickly after the war's end in the 1860s, and used lynching, physical attacks, house burnings and other forms of intimidation to keep African Americans from exercising their political rights. Although the first Klan was disrupted by prosecution by the Federal government in the early 1870s, other groups persisted. By the mid-to-late-1870s, some upper class Southerners created increasing resistance to the altered social structure. Paramilitary organizations such as the White League in Louisiana (1874), the Red Shirts in Mississippi (1875) and rifle clubs, all "White Line" organizations, used organized violence against Republicans, both black and white, to remove Republicans from political office, repress and bar black voting, and restore the Democratic Party to power.[67] In 1876 white Democrats regained power in most of the state legislatures. They began to pass laws designed to strip African Americans and poor whites from the voter registration rolls. The success of late-19th century interracial coalitions in several states inspired a reaction among some white Democrats, who worked harder to prevent both groups from voting.[68]

Despite discrimination, many blacks became property owners in areas that were still developing. For instance, 90% of the Mississippi's bottomlands were still frontier and undeveloped after the war. By the end of the century, two-thirds of the farmers in Mississippi's Delta bottomlands were black. They had cleared the land themselves and often made money in early years by selling off timber. Tens of thousands of migrants went to the Delta, both to work as laborers to clear timber for lumber companies, and many to develop their own farms.[69] Nonetheless, the long agricultural depression, along with disenfranchisement and lack of access to credit, led to many blacks in the Delta losing their property by 1910 and becoming sharecroppers or landless workers over the following decade. More than two generations of free African Americans lost their stake in property.[70]

Nearly all Southerners, black and white, suffered economically as a result of the Civil War. Within a few years cotton production and harvest was back to pre-war levels, but low prices through much of the 19th century hampered recovery. They encouraged immigration by Chinese and Italian laborers into the Mississippi Delta. While the first Chinese entered as indentured laborers from Cuba, the majority came in the early 20th century. Neither group stayed long at rural farm labor.[71] The Chinese became merchants and established stores in small towns throughout the Delta, establishing a place between white and black.[72]

Migrations continued in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among both blacks and whites. In the last two decades of the 19th century about 141,000 blacks left the South, and more after 1900, totaling a loss of 537,000. After that the movement increased in what became known as the Great Migration from 1910 to 1940, and the Second Great Migration through 1970. Even more whites left the South, some going to California for opportunities and others heading to Northern industrial cities after 1900. Between 1880 and 1910, the loss of whites totaled 1,243,000.[73] Five million more left between 1940 and 1970.

From 1890 to 1908, ten of the eleven former Confederate states, along with Oklahoma upon statehood, passed disenfranchising constitutions or amendments that introduced voter registration barriers – such as poll taxes, residency requirements and literacy tests – that were hard for minorities to meet. Most African Americans, most Mexican Americans, and tens of thousands of poor whites were disenfranchised, losing the vote for decades. In some states, grandfather clauses temporarily exempted white illiterates from literacy tests. The numbers of voters dropped drastically throughout the former Confederacy as a result. This can be seen via the feature "Turnout in Presidential and Midterm Elections" at the University of Texas’ Politics: Barriers to Voting. Alabama, which had established universal white suffrage in 1819 when it became a state, also substantially reduced voting by poor whites.[74][75] Democrat-controlled legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to segregate public facilities and services, including transportation.

While African Americans, poor whites and civil rights groups started litigation against such provisions in the early 20th century, for decades Supreme Court decisions overturning such provisions were rapidly followed by new state laws with new devices to restrict voting. Most blacks in the former Confederacy and Oklahoma could not vote until 1965, after passage of the Voting Rights Act and Federal enforcement to ensure people could register. Despite increases in the eligible voting population with the inclusion of women, blacks, and those eighteen and over throughout this period, turnout in ex-Confederate states remained below the national average throughout the 20th century.[76] Not until the late 1960s did all American citizens regain protected civil rights by passage of legislation following the leadership of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Historian William Chafe has explored the defensive techniques developed inside the African American community to avoid the worst features of Jim Crow as expressed in the legal system, unbalanced economic power, and intimidation and psychological pressure. Chafe says "protective socialization by blacks themselves" was created inside the community in order to accommodate white-imposed sanctions while subtly encouraging challenges to those sanctions. Known as "walking the tightrope," such efforts at bringing about change were only slightly effective before the 1920s, but did build the foundation that younger African Americans deployed in their aggressive, large-scale activism during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.[77]

Economy from 1880s through 1930s[]

At the end of the 19th century, white Democrats in the South had created state constitutions that were hostile to industry and business development, with anti-industrial laws extensive from the time new constitutions were adopted in the 1890s.[78] Banks were few and small; there was little access to credit. Traditional agriculture persisted across the region. Especially in Alabama and Florida, rural minorities held control in many state legislatures long after population had shifted to industrializing cities, and legislators resisted business and modernizing interests: Alabama refused to redistrict between 1901 and 1972, long after major population and economic shifts to cities. For decades Birmingham generated the majority of revenue for the state, for instance, but received little back in services or infrastructure.[79]

In the late 19th century, Texas rapidly expanded its railroad network, creating a network of cities connected on a radial plan and linked to the port of Galveston. It was the first state[citation needed]in which urban and economic development proceeded independently of rivers, the primary transportation network of the past. A reflection of increasing industry were strikes and labor unrest: "in 1885 Texas ranked ninth among forty states in number of workers involved in strikes (4,000); for the six-year period it ranked fifteenth. Seventy-five of the one hundred strikes, chiefly interstate strikes of telegraphers and railway workers, occurred in the year 1886."[80]

By 1890, Dallas became the largest city in Texas, and by 1900 it had a population of more than 42,000, which more than doubled to over 92,000 a decade later. Dallas was the harnessmaking capital of the world and a center of other manufacturing. As an example of its ambitions, in 1907 Dallas built the Praetorian Building, fifteen storeys tall and the first skyscraper west of the Mississippi, soon to be followed by other skyscrapers.[81] Texas was transformed by a railroad network linking five important cities, among them Houston with its nearby port at Galveston, Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, and El Paso. Each exceeded fifty thousand in population by 1920, with the major cities having three times that population.[82]

Business interests were ignored by the Southern Democrat ruling class. Nonetheless, major new industries started developing in cities such as Atlanta, GA; Birmingham, AL; and Dallas, Fort Worth and Houston, Texas. Growth began occurring at a geometric rate. Birmingham became a major steel producer and mining town, with major population growth in the early decades of the 20th century.

The first major oil well in the South was drilled at Spindletop near Beaumont, Texas, on the morning of January 10, 1901. Other oil fields were later discovered nearby in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and under the Gulf of Mexico. The resulting "Oil Boom" permanently transformed the economy of the West South Central states and produced the richest economic expansion after the Civil War.[83][84]

In the early 20th century, invasion of the boll weevil devastated cotton crops in the South, producing an additional catalyst to African Americans' decisions to leave the South. From 1910 to 1970, more than 6.5 million African Americans left the South in the Great Migration to Northern and Western cities, defecting from persistent lynching, violence, segregation, poor education, and inability to vote. Black migration transformed many Northern and Western cities, creating new cultures and music. Many African Americans, like other groups, became industrial workers; others started their own businesses within the communities. Southern whites also migrated to industrial cities like Chicago, Detroit, Oakland, and Los Angeles, where they took jobs in the booming new auto and defense industry.

Later, the Southern economy was dealt additional blows by the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the economy suffered significant reversals and millions were left unemployed. Beginning in 1934 and lasting until 1939, an ecological disaster of severe wind and drought caused an exodus from Texas and Arkansas, the Oklahoma Panhandle region, and the surrounding plains, in which over 500,000 Americans were homeless, hungry and jobless.[85] Thousands would leave the region to seek economic opportunities along the West Coast.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt noted the South as the "number one priority" in terms of need of assistance during the Great Depression. His administration created programs such as the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1933 to provide rural electrification and stimulate development. Locked into low-productivity agriculture, the region's growth was slowed by limited industrial development, low levels of entrepreneurship, and the lack of capital investment.

Economy from 1940s through 20th century[]

World War II marked a time of dramatic change within the South from an economic standpoint, as new industries and military bases were developed by the Federal government, providing much needed capital and infrastructure in many regions. People from all parts of the US came to the South for military training and work in the region's many bases and new industries. During and after the war millions of hard-scrabble farmers, both white and black, left agriculture for other occupations and urban jobs.[86][87][88]

The United States began mobilizing for war in a major way in the spring of 1940. The warm weather of the South proved ideal for building 60% of the Army's new training camps and nearly half the new airfields. In all, 40% of spending on new military installations went to the South. For example, in 1940 the small town of 1500 people in Starke, Florida, became the base of Camp Blanding. By March 1941, 20,000 men were constructing a permanent camp for 60,000 soldiers. Money flowed freely for the war effort, as over $4 billion went into military facilities in the South, and another $5 billion into defense plants. Major shipyards were built in Virginia, and Charleston, SC, and along the Gulf Coast. Huge warplane plants were opened in Dallas-Fort Worth and Georgia. The most secret and expensive operation was at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where unlimited amounts of locally generated electricity were used to prepare uranium for the atom bomb.[89] The number of production workers doubled during the war. Most training centers, factories and shipyards were closed in 1945, but not all, and the families that left hardscrabble farms remained to find jobs in the growing urban South. The region had finally reached the take off stage into industrial and commercial growth, although its income and wage levels lagged well behind the national average. Nevertheless, as George B. Tindall notes, the transformation was, "The demonstration of industrial potential, new habits of mind, and a recognition that industrialization demanded community services."[90][91]

Per capita income jumped 140% from 1940 to 1945, compared to 100% elsewhere in the United States. Southern income rose from 59% to 65%. Dewey Grantham says the war, "brought an abrupt departure from the South's economic backwardness, poverty, and distinctive rural life, as the region moved perceptively closer to the mainstream of national economic and social life."[92]

Farming shifted from cotton and tobacco, to include cattle, rice, soybeans, corn, and other foods. Industrial growth increased in the 1960s and greatly accelerated into the 1980s and 1990s. Several large urban areas in Texas, Georgia, and Florida grew to over four million people. Rapid expansion in industries such as autos, telecommunications, textiles, technology, banking, and aviation gave some states in the South an industrial strength to rival large states elsewhere in the country. By the 2000 census, the South (along with the West) was leading the nation in population growth. With this growth however, has come long commute times and air pollution problems in cities such as Dallas, Houston, Atlanta, Austin, Charlotte, and others that rely on sprawling development and highway networks.[93]

Modern economy[]

In the late 20th century, the South changed dramatically. It saw a boom in its service economy, manufacturing base, high technology industries, and the financial sector. Texas in particular witnessed dramatic growth and population change with the dominance of the energy industry and tourism industries, such as the Alamo Mission in San Antonio. Tourism in Florida and along the Gulf Coast also grew steadily throughout the last decades of the 20th century.

Numerous new automobile production plants have opened in the region, or are soon to open, such as Mercedes-Benz in Tuscaloosa, Alabama; Hyundai in Montgomery, Alabama; the BMW production plant in Spartanburg, South Carolina; Toyota plants in Georgetown, Kentucky, Blue Springs, Mississippi and San Antonio; the GM manufacturing plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee; a Honda factory in Lincoln, Alabama; the Nissan North American headquarters in Franklin, Tennessee and factories in Smyrna, Tennessee and Canton, Mississippi; a Kia factory in West Point, Georgia; and the Volkswagen Chattanooga Assembly Plant in Tennessee.

The two largest research parks in the country are located in the South: Research Triangle Park in North Carolina (the world's largest) and the Cummings Research Park in Huntsville, Alabama (the world's fourth largest).

In medicine, the Texas Medical Center in Houston has achieved international recognition in education, research, and patient care, especially in the fields of heart disease, cancer, and rehabilitation. In 1994 the Texas Medical Center was the largest medical center in the world including fourteen hospitals, two medical schools, four colleges of nursing, and six university systems.[94] The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center is consistently ranked the #1 cancer research and treatment center in the United States.[95]

Many major banking corporations have headquarters in the region. Bank of America is in Charlotte, North Carolina. Wachovia was headquartered there before its purchase by Wells Fargo. Regions Financial Corporation is in Birmingham, as is AmSouth Bancorporation, and BBVA Compass. SunTrust Banks is located in Atlanta as is the district headquarters of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. BB&T is headquartered in Winston-Salem.

Many corporations are headquartered in Atlanta and its surrounding area, such as The Coca-Cola Company, Delta Air Lines, and The Home Depot, and also to many cable television networks, such as the Turner Broadcasting System (CNN, TBS, TNT, Turner South, Cartoon Network) and The Weather Channel. In recent years some southern states, most notably Texas, have lured companies with lower tax burdens and lower cost of living for their workforce. In 2019, Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Southern states included: Texas with 50, Virginia with 21, Florida with 18, Georgia with 17, North Carolina with 11, and Tennessee with 10.[96] This economic expansion has enabled parts of the South to report some of the lowest unemployment rates in the United States.[97]

Even with certain southern states and areas doing well economically, many southern states and areas still have high poverty rates when compared to the U.S. nationally. In the U.S. top ten poorest big cities of 2010, the South was represented in the rankings by two cities: Miami, Florida and Memphis, Tennessee.[98] In 2011, nine out of ten poorest states were in the South region.[99]

Education[]

Southern public schools in the past have ranked in the lower half of some national surveys.[100] When allowance for race is considered, a 2007 US Government list of test scores often shows white fourth and eighth graders performing better than average for reading and math; while black fourth and eighth graders also performed better than average.[101] This comparison does not hold across the board. Mississippi often scores lower than national averages, no matter how statistics are compared. Newer data from 2009 suggests that secondary school education in the South is on par nationally, with 72% of high schoolers graduating compared to 73% nationwide.[102]

Culture[]

Several Southern states (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) were British colonies that sent delegates to sign the Declaration of Independence and then fought against the government along with the Northern colonies during the Revolutionary War.[103] The basis for much Southern culture derives from the pride in these states being among the original Thirteen Colonies, and from the fact that much of the population of the South has strong ancestral links to Colonists who emigrated west. Southern manners and customs reflect the relationship with England that was held by the early population.

Overall, the South has had lower housing values, lower household incomes, and lower cost of living than the rest of the United States.[104] These factors, combined with the fact that Southerners have continued to maintain strong loyalty to family ties, has led some sociologists to label white Southerners an ethnic or quasi-ethnic group,[105][106] though this interpretation has been subject to criticism on the grounds that proponents of the view do not satisfactorily indicate how Southerners meet the criteria of ethnicity.[107]

The predominant culture of the South has its origins with the settlement of the region by large groups of people from parts of southern England such as Sussex, Kent, the West Country, and East Anglia who moved to the Tidewater and the eastern parts of the Deep South in the 17th and early 18th centuries, Northern English, Scots lowlanders and Ulster-Scots (later called the Scotch-Irish) who settled in Appalachia and the Upland South in the mid to late 18th century,[108] and the many African slaves who were part of the Southern economy. African American descendants of the slaves brought into the South compose the United States' second-largest racial minority, accounting for 12.1% of the total population according to the 2000 census. Despite Jim Crow era outflow to the North, the majority of the black population remains concentrated in Southern states, and has heavily contributed to the cultural blend of religion, food, art, and music (see spiritual, blues, jazz, R&B, soul music, country music, zydeco, bluegrass and rock and roll) that characterize Southern culture today.

In previous censuses, the largest ancestry group identified by Southerners was English or mostly English,[48][109][110] with 19,618,370 self-reporting "English" as an ancestry on the 1980 census, followed by 12,709,872 listing "Irish" and 11,054,127 "Afro-American".[48][109][110] Almost a third of all Americans who claim English ancestry can be found in the American South, and over a quarter of all Southerners claim English descent as well.[111]

Religion[]

The South has had a majority of its population adhering to evangelical Protestantism ever since the Second Great Awakening,[112] although the upper classes often stayed Anglican/Episcopalian or Presbyterian. The First Great Awakening and the Second Great Awakening from about 1742 about 1850 generated large numbers of Methodists and Baptists, which remain the two main Christian confessions in the South.[113] By 1900, the Southern Baptist Convention had become the largest Protestant denomination in the whole United States with its membership concentrated in rural areas of the South.[114][115] Baptists are the most common religious group, followed by Methodists, Pentecostals and other denominations. Roman Catholics historically were concentrated in Maryland, Louisiana, and Hispanic areas such as South Texas and South Florida and along the Gulf Coast. The great majority of black Southerners are either Baptist or Methodist.[116] Statistics show that Southern states have the highest religious attendance figures of any region in the United States, constituting the so-called Bible Belt.[117] Pentecostalism has been strong across the South since the late 19th century.[118]

National and International influences[]

Apart from its climate, the living experience in the South increasingly resembles the rest of the nation. The arrival of millions of Northerners and Westerners, mainly since the late 20th century, has reshaped the culture of major metropolitan areas and coastal areas.[119] Observers conclude that collective identity and Southern distinctiveness are declining, particularly when defined against "an earlier South that was somehow more authentic, real, more unified and distinct".[120]

While Hispanics have long been a major factor in Texas, millions more have arrived in other Southern states during the 1990s and early 2000s bringing values not rooted in local traditions.[121][122][123] Historian Raymond Mohl emphasizes the role of NAFTA in lowering trade barriers and facilitating large-scale population movements. He adds other factors such as ongoing economic crisis in Mexico, new more liberal immigration policies in the United States, labor recruitment and smuggling, that have produced a major flow of Mexican and Hispanic migration to the southeast. That region's low-wage, low-skill economy readily hired cheap, reliable, nonunion labor, without asking applicants too many questions about legal status.[124][125] Richard J. Gonzales argues that the rise of La Raza (Mexican American community) in terms of numbers and influence in politics, education, and language and cultural rights will grow rapidly in Texas by 2030 when demographers predict Hispanics will outnumber Anglos in Texas.[126] However thus far their political participation and the Latino vote have been low, so the potential political impact is much higher than the actual one thus far.[127][128]

Scholars have suggested that in the Deep South collective identity and Southern distinctiveness are thus declining, particularly when defined against "an earlier South that was somehow more authentic, real, more unified and distinct".[120] On the other hand, Southerners have moved west in large numbers, especially to California and to the Midwest. Thus, journalist Michael Hirsh proposed that aspects of Southern culture have spread throughout a greater portion of the rest of the United States in a process termed "Southernization".[129]

Sports[]

Racial integration[]

During the 1950s and 1960s, the racial integration of all-white collegiate sports teams was high on the regional agenda. Involved in it were issues of racial equality, racism, and the alumni's demand for the top players who it needed in order to win high-profile games. The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) would take the lead. First they started to schedule integrated teams from the North. The wake-up call came in 1966, when Don Haskins's Texas Western College team with five black starters, upset the all-white University of Kentucky team to win the NCAA national basketball championship.[130] That happened at a time when there were no black varsity basketball teams in either the Southeastern Conference or the Southwest Conference. Finally ACC schools, typically under pressure from boosters and civil rights groups, integrated their sports teams.[131][132] With an alumni base that dominated local and state politics, society and business, the ACC flagship schools were successful in their endeavor – as historian Pamela Grundy argues, they had learned how to win:

- The widespread admiration that athletic ability inspired would help transform athletic fields from grounds of symbolic play to forces for social change, places where a wide range of citizens could publicly and at times effectively challenge the assumptions that cast them as unworthy of full participation in U.S. society. While athletic successes would not rid society of prejudice or stereotype – black athletes would continue to confront racial slurs...[minority star players demonstrated] the discipline, intelligence, and poise to contend for position or influence in every arena of national life.[133]

American football[]

American football is heavily considered the most popular team sport in most areas of the Southern United States.

The region is home to numerous decorated and historic college football programs, particularly in the Southeastern Conference (known as the "SEC"), Atlantic Coast Conference (known as the "ACC"), and the Big 12 Conference. The SEC, consisting entirely of teams based in Southern states, is widely considered to be the strongest league in contemporary college football and includes the Alabama Crimson Tide, the program with the most national championships in the sport's modern history. The sport is also highly competitive and has a spectator following at the high school level, particularly in rural areas, where high school football games often serve as prominent community gatherings.

Though not as popular on a wider basis as the collegiate game, professional football has a growing tradition in the Southern United States. Before league expansion began, the only established professional team based in the South were the Washington Redskins, now called the Washington Football Team. They still retain a large following in most of Virginia, and parts of Maryland.[134] Later on, the National Football League began to expand many teams in the Southern U.S. during the 1960s, with franchises like the Atlanta Falcons, New Orleans Saints, Houston Oilers, Miami Dolphins, and most prominently the Dallas Cowboys, who overtook Washington as the region's most popular team and eventually became widely considered the most popular team in the United States. In later decades, NFL expansion into Southern states continued, with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers during the 1970s, along with the Carolina Panthers and Jacksonville Jaguars during the 1990s. The Houston Oilers were eventually replaced by the Houston Texans, after the Oilers relocated to Nashville to become the Tennessee Titans.

| Rank | Team | Sport | League | Attendance (avg/game)[135] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alabama Crimson Tide | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 101,562 |

| 2 | LSU Tigers | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 100,819 |

| 3 | Texas A&M Aggies | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 99,844 |

| 4 | Texas Longhorns | Football | NCAA (Big 12) | 97,713 |

| 5 | Tennessee Volunteers | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 92,984 |

| 6 | Georgia Bulldogs | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 92,746 |

| 7 | Oklahoma Sooners | Football | NCAA (Big 12) | 86,735 |

| 8 | Auburn Tigers | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 84,462 |

| 9 | Florida Gators | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 82,328 |

| 10 | Clemson Tigers | Football | NCAA (ACC) | 80,400 |

| 11 | South Carolina Gamecocks | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 73,628 |

| 12 | Florida State Seminoles | Football | NCAA (ACC) | 68,288 |

| 13 | Miami Hurricanes | Football | NCAA (ACC) | 61,469 |

| 14 | Louisville Cardinals | Football | NCAA (ACC) | 61,290 |

| 15 | Oklahoma State Cowboys | Football | NCAA (Big 12) | 60,218 |

| 16 | Arkansas Razorbacks | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 59,884 |

| 17 | Virginia Tech Hokies | Football | NCAA (ACC) | 59,574 |

| 18 | West Virginia Mountaineers | Football | NCAA (Big 12) | 58,158 |

| 19 | Mississippi State Bulldogs | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 58,057 |

| 20 | Kentucky Wildcats | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 57,572 |

| 21 | NC State Wolfpack | Football | NCAA (ACC) | 56,855 |

| 22 | Texas Tech Red Raiders | Football | NCAA (Big 12) | 56,034 |

| 23 | Ole Miss Rebels | Football | NCAA (SEC) | 55,685 |

| 24 | Baylor Bears | Football | NCAA (Big 12) | 44,915 |

Baseball[]

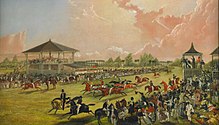

Baseball has been played in the Southern United States dating back to the mid-19th century. It was traditionally more popular than American football until the 1980s, and still accounts for the largest annual attendance amongst sports played in the South. The first mention of a baseball team in Houston was on April 11, 1861.[136][137] During the late 19th century and early 20th century games were common, especially once the professional leagues such as the Texas League, the Dixie League, and the Southern League were organized.

The short-lived Louisville Colonels were a part of the early National League and American Association, but ceased to exist in 1899. The first Southern Major League Baseball team after the Colonels appeared in 1962, when the Houston Colt .45s (known today as the Houston Astros) were enfranchised. Later, the Atlanta Braves came in 1966, followed by the Texas Rangers in 1972, and finally the Miami Marlins and Tampa Bay Rays in the 1990s.

College baseball appears to be more well attended in the Southern U.S. than elsewhere, as teams like Florida State, Arkansas, LSU, Virginia, Mississippi State, Ole Miss, South Carolina, Florida and Texas are commonly at the top of the NCAA's attendance.[138] The South generally produces very successful collegiate baseball teams with Virginia, Vanderbilt, LSU, South Carolina, Florida and Coastal Carolina winning recent College World Series Titles.

The following is a list of each MLB team in the Southern U.S. and the total fan attendance for 2019:

| Rank | Team | League | 2019 overall annual attendance[139] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Houston Astros | American League | 2,857,367 |

| 2 | Atlanta Braves | National League | 2,654,920 |

| 3 | Washington Nationals | National League | 2,259,781 |

| 4 | Texas Rangers | American League | 2,133,004 |

| 5 | Baltimore Orioles | American League | 1,307,807 |

| 6 | Tampa Bay Rays | American League | 1,178,735 |

| 7 | Miami Marlins | National League | 811,302 |

Auto racing[]

The Southern states are commonly associated with stock car racing and its most prominent competition level NASCAR, which is headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina and Daytona Beach, Florida. The sport was developed in the South during the early 20th century, with stock car racing's historic mecca being Daytona Beach, where cars initially raced on the wide, flat beachfront, before the construction of Daytona International Speedway. Though the sport has attained a following throughout the United States, a majority of NASCAR races continue to take place at Southern tracks.

Basketball[]

Basketball is very popular throughout the Southern United States as both a recreational and spectator sport, particularly in the states of Kentucky and North Carolina. Both states are home to several prominent college basketball programs, including the Kentucky Wildcats, Louisville Cardinals, Duke Blue Devils and North Carolina Tar Heels.

NBA teams based in the South include the San Antonio Spurs, Houston Rockets, Oklahoma City Thunder, Dallas Mavericks, Washington Wizards, Charlotte Hornets, Atlanta Hawks, Orlando Magic, Memphis Grizzlies, New Orleans Pelicans, and Miami Heat. The Spurs and Heat in particular have become prominent within the NBA, with eight championships won by the two between 1999 and 2013.

Golf[]

Golf is a popular recreational sport in most areas of the South, with the region's warm climate allowing it to host many professional tournaments and numerous destination golf resorts, particularly in the state of Florida. The region is home to The Masters, one of the four major championships in professional golf. The Masters is played at Augusta National Golf Club in Augusta, Georgia, and has become one of the professional game's most important tournaments.

Soccer[]

In recent decades association football, known in the South as in the rest of the United States as "soccer", has become a popular sport at youth and collegiate levels throughout the region. The game has been historically widespread at the college level in the Atlantic coast states of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas; which contain many of the nation's most successful college soccer programs.

The establishment of Major League Soccer has led to professional soccer clubs in the Southern cities including FC Dallas, Houston Dynamo, D.C. United, Orlando City, Inter Miami CF, Nashville SC, Atlanta United and the future Austin FC and Charlotte FC. The current United States second division soccer league, the USL Championship, was initially geographically based in the coastal Southeast around clubs in Charleston, Richmond, Charlotte, Wilmington, Raleigh, Virginia Beach, and Atlanta.

Major sports teams in the South[]

The Southern region is home to numerous professional sports franchises in the "Big Four" leagues (NFL, NBA, NHL, and MLB), with many championships collectively among them.

- Dallas-Fort Worth: Cowboys (NFL), Rangers (MLB), Mavericks (NBA), Stars (NHL)

- Washington, D.C.: Washington Football Team (NFL), Nationals (MLB), Wizards (NBA), Capitals (NHL)

- Miami-Fort Lauderdale: Dolphins (NFL), Marlins (MLB), Heat (NBA), Panthers (NHL)

- Houston: Texans (NFL), Astros (MLB), Rockets (NBA)

- Atlanta: Falcons (NFL), Braves (MLB), Hawks (NBA)

- Tampa Bay: Buccaneers (NFL), Rays (MLB), Lightning (NHL)

- Baltimore: Ravens (NFL), Orioles (MLB)

- Charlotte: Panthers (NFL), Hornets (NBA)

- Nashville: Titans (NFL), Predators (NHL)

- New Orleans: Saints (NFL), Pelicans (NBA)

- Orlando: Magic (NBA)

- San Antonio: Spurs (NBA)

- Jacksonville: Jaguars (NFL)

- Oklahoma City: Thunder (NBA)

- Memphis: Grizzlies (NBA)

- Raleigh: Hurricanes (NHL)

Health[]

Nine Southern states have obesity rates exceeding 30% of the population, the highest in the country. Those states include: Mississippi, Louisiana, West Virginia, Alabama, Oklahoma, Arkansas, South Carolina, Kentucky and Texas.[140][141] Rates for hypertension and diabetes for these states are also the highest in the nation.[141] A study reported that six Southern states have the worst incidence of sleep disturbances in the nation, attributing the disturbances to high rates of obesity and smoking.[142] The South has a higher percentage of obese people[143] and diabetics when compared to national regional averages.[144] The region also has the largest number of people dying from stroke complications[145] and the highest rates of cognitive decline.[146] Life expectancy is lower and death rates are higher, when compared to national averages of other regions in the United States.[147][148] This disparity reflects substantial divergence between the South and other regions since the middle of the 20th century.[149]

The East South Central Census Division of the United States (made up of Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama) had the highest rate of inpatient hospital stays in 2012. The other divisions, West South Central (Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana) and South Atlantic (West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida) ranked seventh and fifth.[150] The South had a significantly higher rate of hospital discharges in 2005 than other regions of the United States, but the rate had declined to be closer to the overall national rate by 2011.[151]

For cancer causes, the South, particularly an axis from West Virginia through Texas, leads the nation in adult obesity, adult smoking, low exercise, low fruit consumption, low vegetable consumption, all known cancer risk factors,[152] which matches a similar high risk axis in "All Cancers Combined, Death Rates by State, 2011" from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[153]

Politics[]

In the first decades after Reconstruction (1880s–1890s), white Democrats regained power in the state legislatures, and began to make voter registration more complicated, to reduce black voting. With a combination of intimidation, fraud and violence by paramilitary groups, they suppressed black voting and turned Republicans out of office. From 1890 to 1908, ten of eleven states ratified new constitutions or amendments that effectively disenfranchised most black voters and many poor white voters. This disenfranchisement persisted for six decades into the 20th century, depriving blacks and poor whites of all political representation. Because they could not vote, they could not sit on juries. They had no one to represent their interests, resulting in state legislatures consistently underfunding programs and services, such as schools, for blacks and poor whites.[154] Scholars have characterized pockets of the Southern United States as being "authoritarian enclaves" from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Act.[12][13][14][15]

With the collapse of the Republican Party in nearly all parts of the South, the region became known as the “Solid South”, and the Democratic Party after 1900 moved to a system of primaries to select their candidates. Victory in a primary was tantamount to election. From the late 1870s to the 1960s, only rarely was a state or national Southern politician a Republican, outside from Southern Republican strongholds within the Appalachian mountain districts.[155][156] Southern Republicans during this time period would continue to control parts of the Appalachian Mountain areas and compete for power in the former Border States. Apart from a few states (such as the Byrd Machine in Virginia, the Crump Machine in Memphis), and a few other local organizations, the Democratic Party itself was very lightly organized. It managed primaries but party officials had little other role. To be successful a politician built his own network of friends, neighbors and allies. Reelection was the norm, and the result from 1910 to the late 20th century was that Southern Democrats in Congress had accumulated seniority, and automatically took the chairmanships of all committees.[157] By the 1940s the Supreme Court began to find disenfranchisement measures like the “grandfather clause” and the white primary unconstitutional. Southern legislatures quickly passed other measures to keep blacks disenfranchised, even after suffrage was extended more widely to poor whites. Because white Democrats controlled all the Southern seats in the U.S. Congress, they had outsize power and could sidetrack or filibuster efforts to pass legislation they didn't agree with.

Increasing support for civil rights legislation by the national Democratic Party beginning in 1948 caused segregationist Southern Democrats to nominate Strom Thurmond on a third-party “Dixiecrat” ticket in 1948. These Dixiecrats returned to the party by 1950, but Southern Democrats held off Republican inroads in the suburbs by arguing that only they could defend the region from the onslaught of northern liberals and the civil rights movement. In response to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling of 1954, 101 Southern congressmen (19 senators, 82 House members of which 99 were Southern Democrats and 2 were Republicans) in 1956 denounced the Brown decisions as a "clear abuse of judicial power [that] climaxes a trend in the federal judiciary undertaking to legislate in derogation of the authority of Congress and to encroach upon the reserved rights of the states and the people." The manifesto lauded, “...those states which have declared the intention to resist enforced integration by any lawful means”. It was signed by all Southern senators except Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson, and Tennessee senators Albert Gore Sr. and Estes Kefauver. Virginia closed schools in Warren County, Prince Edward County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk rather than integrate, but no other state followed suit. Democratic governors Orval Faubus of Arkansas, Ross Barnett of Mississippi, John Connally of Texas, Lester Maddox of Georgia, and, especially, George Wallace of Alabama resisted integration and appealed to a rural and blue-collar electorate.[158]

The northern Democrats’ support of civil rights issues culminated when Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which ended legal segregation and provided federal enforcement of voting rights for blacks. In the presidential election of 1964, Barry Goldwater’s only electoral victories outside his home state of Arizona were in the states of the Deep South where few blacks could vote before the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[159] Pockets of resistance to integration in public places broke out in violence during the 1960s by the shadowy Ku Klux Klan, which caused a backlash among moderates.[160] Major resistance to school busing extended into the 1970s.[161]

National Republicans such as Richard Nixon began to develop their Southern strategy to attract conservative white Southerners, especially the middle class and suburban voters, in addition to migrants from the North and traditional GOP pockets in Appalachia. The transition to a Republican stronghold in the South took decades. First, the states started voting Republican in presidential elections, except for native southerners Jimmy Carter in 1976 and Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996. Then the states began electing Republican senators and finally governors. Georgia was the last state to do so, with Sonny Perdue taking the governorship in 2002.[162] In addition to its middle class and business base, Republicans cultivated the religious right and attracted strong majorities from the evangelical or Fundamentalist vote, mostly Southern Baptists, which had not been a distinct political force prior to 1980.[163]

Decline of Southern liberalism during the 20th century[]

Southern liberals were an essential part of the New Deal coalition – without them Roosevelt lacked majorities in Congress. Typical leaders were Lyndon B. Johnson in Texas, Jim Folsom and John Sparkman in Alabama, Claude Pepper in Florida, Earl Long and Hale Boggs in Louisiana, Luther H. Hodges in North Carolina, and Estes Kefauver in Tennessee. They promoted subsidies for small farmers, and supported the nascent labor union movement. An essential condition for this north–south coalition was for northern liberals to ignore the problem of racism throughout the South and elsewhere in the country. After 1945, however, northern liberals – led especially by young Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota – increasingly made civil rights a central issue. They convinced Truman to join them in 1948. The conservative Southern Democrats – the Dixiecrats – took control of the state parties in half the region and ran Strom Thurmond for president against Truman. Thurmond carried only the Deep South, but that threat was enough to guarantee the national Democratic Party in 1952 and 1956 would not make civil rights a major issue. In 1956, 101 of the 128 southern congressmen and senators signed the Southern Manifesto denouncing forced desegregation.[164] The labor movement in the South was divided, and lost its political influence. Southern liberals were in a quandary – most of them kept quiet or moderated their liberalism, others switched sides, and the rest continued on the liberal path. One by one, the last group was defeated; historian Numan V. Bartley states, "Indeed, the very word 'liberal' gradually disappeared from the southern political lexicon, except as a term of opprobrium."[165]

Presidents from the South[]

The South produced nine of the country's first twelve Presidents. After Zachary Taylor won the presidential election of 1848, no Southern politician was elected president until Woodrow Wilson in 1912. Andrew Johnson (of Tennessee) who was vice president in 1865, became president after the death of Abraham Lincoln. Out of the last eleven U.S. presidents, six have Southern region ties: Lyndon B. Johnson (of Texas; 1963–69), Jimmy Carter (of Georgia; 1977–81), George H. W. Bush (of Texas; 1989–93), Bill Clinton (of Arkansas; 1993–2001), George W. Bush (of Texas; 2001–2009), and Joe Biden (of Delaware; 2021–present). Johnson was a native of Texas, while Carter is from Georgia, and Clinton from Arkansas. While George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush began their political careers in Texas, they were both born in New England and have their ancestral roots in that region. Similarly, while Joe Biden was born in Pennsylvania, he grew up largely in Delaware (classified as a Southern state by the U.S. Census Bureau) and spent his entire political career there.

Other politicians and political movements[]

The South has produced various nationally known politicians and political movements. In 1948, a group of Democratic congressmen, led by Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, split from the Democrats in reaction to an anti-segregation speech given by Minneapolis mayor and future senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. They founded the States Rights Democratic or Dixiecrat Party. During that year's presidential election, the party ran Thurmond as its candidate and he carried four Deep South states.

In the 1968 Presidential election, Alabama Governor George C. Wallace ran for president on the American Independent Party ticket. Wallace ran a "law and order" campaign similar to that of Republican candidate, Richard Nixon. Nixon's Southern Strategy of gaining electoral votes downplayed race issues and focused on culturally conservative values, such as family issues, patriotism, and cultural issues that appealed to Southern Baptists.

In the 1994 mid-term elections, another Southern politician, Newt Gingrich, led the Republican Revolution, ushering in twelve years of GOP control of the House. Gingrich became Speaker of the United States House of Representatives in 1995 and served until his resignation in 1999. Tom DeLay was the most powerful Republican leader in Congress[citation needed] until he was indicted under criminal charges in 2005 and was forced to step aside by Republican rules.[citation needed] Apart from Bob Dole from Kansas (1985–96), the recent Republican Senate Leaders have been Southerners: Howard Baker (1981–1985) of Tennessee, Trent Lott (1996–2003) of Mississippi, Bill Frist (2003–2006) of Tennessee, and Mitch McConnell (2007–present) of Kentucky.

The Republicans candidates for president have won the South in elections since 1972, except for 1976. The region is not, however, entirely monolithic, and every successful Democratic candidate since 1976 has claimed at least three Southern states. Barack Obama won Florida, Maryland, Delaware, North Carolina, and Virginia in 2008 but did not repeat his victory in North Carolina during his 2012 reelection campaign.[166] Joe Biden also performed well for a modern Democrat in the South, winning Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and Georgia, in the 2020 United States presidential election.

Race relations[]

Native Americans[]