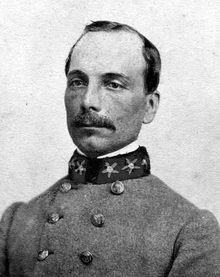

Ambrosio José Gonzales

Ambrosio José Gonzales | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 3, 1818 Matanzas, Cuba |

| Died | July 31, 1893 (aged 74) The Bronx, New York |

| Place of burial | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York *Plot: Lot A, Range 131, Grave 20 |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Chief of Artillery, Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War *Battle of Fort Sumter *Battle of Honey Hill |

Ambrosio José Gonzales (October 3, 1818 – July 31, 1893) was a Cuban revolutionary general who became a colonel in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. Gonzales, as a revolutionary, wanted the United States to annex Cuba.

During the American Civil War, he served as the Chief of Artillery in the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Early life[]

Gonzales was born in the town of Matanzas, Cuba, in 1818. His father was a schoolmaster and the founder of the first daily newspaper in Matanzas. His mother was a member of a prominent local family.[1][2] After the death of his mother,[2] his father sent the nine-year-old Ambrosio to Europe and New York City, where he received his primary and secondary education. He returned to Cuba and attended the University of Havana, where he earned degrees in arts and sciences and later in law, graduating in 1839. He returned to Matanzas and became a teacher[3] and later a professor for the University of Havana, where he taught languages (he claimed fluency in English, French, Spanish, and Italian). He was also well instructed in mathematics and geography.[1][2][4]

In 1845, after the death of his father, he began two years traveling in Europe and the United States, returning to Cuba to resume his post at the university.[4]

Cuban revolutionary[]

In 1848, Gonzales joined with a secret organization, the Havana Club, for Cuba to be annexed by the United States to liberate the island from Spanish rule. That aim was actively shared by many Americans. The movement found encouragement from a surge of expansionism in the US, particularly in its South, after the US annexation of Texas in 1845.[2][4]

The group pursued its goal of annexation by a combination of financial, diplomatic, and military means.[2][4] His association and influence with prominent US Southerners led him to author a manifesto encouraging US to annex Cuba. By 1849, Gonzales became interested in the revolutionary plans of Venezuelan General Narciso López, who ultimately led several military expeditions, known as filibusters, to try to liberate Cuba from Spain rule. Between 1849 and 1851, Gonzales accompanied López in several of his filibuster expeditions. The Spanish authorities set up a trap to capture López, but López was able to escape and sought asylum in the United States.[3]

In 1849, Gonzales became a naturalized US citizen under a law that offered citizenship to free whites who had lived in the country for at least three years before the age of 21.[2] Thereafter, he was commissioned by the Junta of Havana to seek help from General William J. Worth, a United States veteran of the Mexican–American War. Together with Worth, Gonzales was to prepare an expedition of 5,000 North American veterans, who would disembark in Cuba and aid the Cuban patriots, headed by López, who would rise in arms. The plan did not materialize because of Worth's untimely death.[3]

López and Gonzales then organized the Creole expedition with $40,000, which they had acquired by selling Cuban bonds. Among the financiers of the expedition was John A. Quitman, a former general in the US Army who had also participated in the Mexican–American War. López led the expedition with Gonzales as Chief of Staff. On the night of May 19, 1850, López gave the order to advance and Gonzales and his men attacked the Governor's palace. The expedition failed because it lacked the support from the people in the island who did not respond to the filibusters' call and because they were no match for the Spanish military reinforcements. Gonzales, López and their men returned to the Creole. Once it was back at sea, the Creole was chased by the Spanish warship Pizarro and changed its course. The Creole then headed for Key West, Florida, where Gonzales spent three weeks recovering from wounds received in the incident.[4] On December 16, 1850, Lopez, Gonzales, Quitman, and the members of the failed expedition were tried in New Orleans for having violated the laws of neutrality. After three attempts to convict them, the prosecution was abandoned.[3]

Gonzales settled in Beaufort, South Carolina, after the failure of another Lopez expedition to liberate Cuba in 1851. In the US, he continued to seek assistance for Cuban independence, meeting with political leaders including President Franklin Pierce and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.[4]

In 1856, he married Harriet Rutledge Elliot, the 16-year-old daughter of William Elliott (1788–1863), a prominent South Carolina State senator, planter and writer.[4] They became the parents of six children; Ambrose E. Gonzales (1857–1926), Narciso Gener Gonzales (1858–1903), Alfonso Beauregard Gonzales (1861–1908), Gertrude Ruffini Gonzales (1864–1900), Benigno Gonzales (1866–1937), and Anita Gonzales (1869–?).[5][6]

American Civil War[]

As secession approached in the late 1850s, Gonzales went into business as a sales agent for various firearms manufacturers, demonstrating and selling the LeMat revolver and Maynard Arms Company rifles to state legislatures in the South.[4]

Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War, Gonzales joined the Confederate Army as a volunteer on the staff of General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, who had been his schoolmate in New York City.[1] Gonzales was active during the bombardment of Fort Sumter. In his report on the actions of April 12, Beauregard wrote the following:

Monday, May 6, 1861. Official Report of the Bombardment of Fort Sumter.

To my volunteer staff, Messrs. Chisolm, Wigfall, Chesnut, Manning, Miles, Gonzales and Pryor: I am indebted for their indefatigable and valuable assistance, night and day, during the attacks on Sumter, transmitting, in open boats, my orders when called upon, with alacrity and cheerfulness, to the different batteries, amidst falling balls and bursting shells, Captain Wigfall being the first in Sumter to receive its surrender.

I am, sirs, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

G. T. Beauregard,

Brigadier General Commanding

Gonzales, who was serving as a special aide to the governor of South Carolina, submitted plans for the defense of the coastal areas of his homeland state. According to Major Danville Leadbetter in a letter to the Secretary of War:

The project of auxiliary coast defense herewith, as submitted by Col. A. J. Gonzalez, though not thought to be everywhere applicable, is believed to be of great value under special circumstances. In the example assumed at Edisto Island, where the movable batteries rest on defensive works and are themselves scarcely exposed to surprise and capture, a rifled 24-pounder, with two small guns, rallying and reconnoitering from each of the fixed batteries, would prove invaluable. A lighter gun than the 24-pounder, and quite as efficient, might be devised for such service, but this is probably the best now available. Colonel Gonzales’ proposed arrangements for re-enforcing certain exposed and threatened maritime Posts seem to be judicious and to merit attention.

Gonzales was then commissioned as Lieutenant Colonel of artillery and assigned to duty as an inspector of coastal defenses. In 1862, he was promoted to colonel and became Chief of Artillery of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida under General John C. Pemberton. Gonzales was able to fend off Union gunboat attempts to destroy railroads and other important points on the Carolina coast by placing his heavy artillery on special carriages for increased mobility. On November 30, 1864, Gonzales served as artillery commander at the Battle of Honey Hill, the third battle of Sherman's March to the Sea fought in Savannah, Georgia.[7] Confederate President Jefferson Davis declined Gonzales's request for promotion to general six times. Davis disliked Beauregard, one of whose men had been Gonzales. Also, Davis did not consider Gonzales to be command material because of his experience with the failed Cuban filibusters and his contentious relationships with Confederate officers in Richmond, Virginia.[2]

Later years[]

After the war, Gonzales pursued a variety of vocations, all of which were marginally successful, but like many others, he never provided the security he sought for his extended family. His efforts were similar to those of other formerly wealthy Southerners, who sought to recover their estates and social status.[1]

In 1869, Gonzales and his family moved to Cuba, where his wife, Harriet Elliott Gonzales, died of yellow fever. Gonzales returned to South Carolina with four of his children, leaving two children, Narciso and Alfonso, in Cuba with friends for a year. By 1870, the Gonzales children were all back in the United States, where they were raised by their grandmother, Ann Hutchinson Smith Elliott, and their aunts, Ann and Emily Elliott. Gonzales faced not only financial loss but also the death of his wife as well as his sister-in-law's successful efforts to poison the relationships between Gonzales and his children.[2]

Gonzales's sons, Ambrose and Narciso, became notable journalists. In 1891, they founded The State, a newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina. Narciso waged a crusade against Benjamin "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman, a US Senator and former Governor of South Carolina, and his nephew and heir apparent, Lieutenant Governor James H. Tillman, in his newspaper, helping ensure James's defeat in the 1902 South Carolina governor race. On January 15, 1903, Narciso was shot by James (the nephew of Benjamin) and died four days later. A memorial cenotaph for Narciso was later erected on Senate Street across from the State House in Columbia, purportedly on the route on which Tillman regularly walked home.[8]

Ambrose Gonzales is recognized and remembered in South Carolina as a pioneering journalist and the writer of black dialect sketches on the Gullah people of the South Carolina and Georgia Low Country. In 1986, he was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame.[9]

Gonzales became ill as he became older, and his sons sent him to Key West, where Gonzales attended meetings of the Chiefs of the War of 68 and the Delegate of the Cuban Revolutionary Party. He was later interned in a hospital in Long Island, New York. Gonzales died on July 31, 1893, and is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City, Plot: Lot A, Range 131, Grave 20.

Thus, Gonzales missed, by only a few years, the Spanish–American War of 1898, which achieved the cause that he had long championed, the liberation of Cuba from Spanish rule by US military intervention.

See also[]

- Hispanics in the American Civil War

- List of Cuban Americans

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lewis Pinckney Jones (1955), "Ambrosio José Gonzales, a Cuban Patriot in Carolina", The South Carolina Historical Magazine Vol. 56, No. 2, April 1955

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Antonio Rafael de la Cova (2003), Cuban Confederate Colonel: The Life of Ambrosio José Gonzales, The University of South Carolina Press; ISBN 1-57003-496-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Patria (New York)" (translated); December 31, 1892, pages 2–3.; Ambrosio José Gonzalez.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Philip Thomas Tucker (2002), Cubans in the Confederacy: José Agustín Quintero, Ambrosio José Gonzales, and Loreta Janeta Velazquez, McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0976-2, ISBN 978-0-7864-0976-1

- ^ "A South Carolina / Cuba Connection". College of Charleston. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ^ Fripp Hampton, Ann (1979-01-01). "A Sketchbook of the Hampton, Gonzales, and Elliott Families" (PDF). Latin American Studies. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ^ OPERATIONS ON THE COASTS OF SOUTH CAROLINA, GEORGIA, AND MIDDLE AND EAST FLORIDA.

- ^ Jones, Lewis Pinckney (1973). Stormy Petrel: N. G. Gonzales and His State. Columbia, S.C.: South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-253-2.

- ^ Ambrose E. Gonzales (1857–1926) Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, South Carolina Business Hall of Fame website, accessed May 30, 2011

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambrosio José Gonzales. |

- Biography of Colonel Gonzales at latinamericanstudies.org

- Elliott and Gonzales Family Papers

- Works by or about Ambrosio José Gonzales at Internet Archive

- Ambrosio José Gonzales at Find a Grave

- 1818 births

- 1893 deaths

- People from Matanzas

- People of South Carolina in the American Civil War

- Cuban generals

- Confederate States Army officers

- Cuban emigrants to the United States

- People from Beaufort, South Carolina

- Benjamin Tillman

- Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)