Anarchism in Ireland

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

|

Anarchism in Ireland has its roots in the stateless organisation of the túatha in Gaelic Ireland. It first began to emerge from the libertarian socialist tendencies within the Irish republican movement, with anarchist individuals and organisations sprouting out of the resurgent socialist movement during the 1880s, particularly gaining prominence during the time of the Dublin Socialist League.

One of the prominent figures in the Irish socialist republican movement was the syndicalist James Connolly, who led the formation of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union along the lines of industrial unionism and fought in the Easter Rising as part of the Irish Citizens Army. Following the independence of Ireland and the rise of communist tendencies in the country, some left-wing republicans began to gravitate towards anarchism, including Jack White, who himself became an anarchist while fighting on the side of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

It was only in the late 1960s that a specifically anarchist movement began to emerge, in the context of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland and the outbreak of the Troubles. A number of small local groups formed and dissolved throughout the 1970s before the establishment of the Workers Solidarity Movement (WSM) in 1984, which continued to exist as a national platformist federation up until it’s disbandment on 8 December 2021.[1] There has since been a large growth of anarchist activity in Ireland following the rise of the anti-globalization movement at the turn of the 21st century.

Statelessness in Gaelic Ireland[]

Before the Tudor conquest during the 16th century, Gaelic Ireland was largely stateless, even being described as "anarchic" by the Irish historian Goddard Henry Orpen, although this characterisation was disputed by Irish nationalists such as Eoin MacNeill. Gaelic Irish society was largely built around kinship and had few if any political institutions, with the early Irish law scholar D. A. Binchy having written about the absence of any legislature, bailiffs or police, and noting "no trace of State-administered justice". The historian Kathleen Hughes even argued that one of the reasons that it took more than five hundred years for the English conquest of Ireland to finally be achieved, was precisely because of the lack of a centralised state in Ireland, as Irish people were reticent to give up their freedoms to any state.[2]

The basic polity form of Gaelic Ireland was the Túath, a voluntary assembly of free men that democratically decided how to take action on the issues of the time, with the ability to elect their own kings, resolve matters of war and peace, and institute their own policy.[3] The kings themselves had minimal power, strictly limited to acting as a local military leader and presiding over the assemblies of the túath, which themselves held ultimate legislative power.[4]

Laws were passed down orally by a class of professional jurists known as Brehons who could be consulted by túatha and enforced by groups of private individuals through a system of sureties, which were the basis for almost all legal transactions. Common tactics to resolve disputes included mutual fasting between plaintiffs and defendants, in which the one that broke their fast or refused to submit to adjudication would "los[e] their honor within the community", with the harshest punishments that communities dealt out being outlawing and exile.[5] The Gaelic Irish also did not mint nor issue their own coinage, despite Viking and later English colonists having done so, which allowed for fair and equal exchange to take place.[6]

When the Anglo-Norman invasion established the Lordship of Ireland in 1171, native Gaelic institutions came under some strain as they attempted to adapt to the political system brought by the new state. The conquest of Ireland culminated under the Tudors, who established the centralised Kingdom of Ireland in 1542 and suppressed the last holdouts of rebellion by 1603, finalizing the "destruction of the old anarchic society".[7]

The Plantations of Ireland brought on another series of rebellions against increasing anti-Catholic discrimination, culminating in the Irish Confederate Wars, during which the Irish Catholic Confederation briefly re-established self-governance in Ireland before eventually being conquered by the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell. Following the Glorious Revolution, Irish Jacobites attempted to restore James II to the throne, but they were defeated and Williamite rule was successfully secured over Ireland.

Origins[]

One of the earliest examples of anarchism in Ireland was in the early work of the Anglo-Irish political philosopher Edmund Burke. A Vindication of Natural Society, though intended as a satire of Henry St John's deism,[8] elaborated one of the first literary expressions of philosophical anarchism, which inspired the works of the English radical William Godwin and was later praised by the American individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker.[9] Some libertarian scholars have insisted that Burke was initially sincere in his anarchist views, but later disowned them in order to advance his political career,[10][11] although this characterisation has since been disputed.[12]

In 1765, Burke was elected to the Parliament of Great Britain, where he became a leading spokesperson of the Rockingham Whigs around Charles Watson-Wentworth and a prominent defender of the American Revolution. But following the outbreak of the French Revolution, Burke had himself become a proponent of conservatism and lost support from many of his former Whig allies. As part of this wave of Atlantic Revolutions, rising support for Irish republicanism culminated with the Irish Rebellion of 1798, organised by the French-backed Society of United Irishmen.[13] Despite the defeat of this insurrection and Ireland's incorporation into the United Kingdom, republicanism persisted, with its left-wing tendencies laying the groundwork for what would grow into libertarian socialism and anarchism.[14]

Socialism[]

Following the events surrounding the Paris Commune, efforts were made to establish branches of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA) in Ireland, led by Joseph Patrick McDonnell, the Irish representative on the IWA's General Council. In February 1872, a branch of the IWA was established in Dublin by Richard McKeon, but its activities quickly came under attack by anti-communist mobs, which forced its premature closure on 7 April of the same year. A Cork branch had also been established in February, to more success, gaining 300 members within weeks. When an anti-communist meeting was called by city officials on 24 March, a hundred internationalist workers wearing green neckties disrupted the meeting, themselves taking control of the stage after several hours of conflict with its organisers. But like the Dublin branch, the Cork branch was itself driven out of the city amid a "red scare" driven by the local clergy. There were other short-lived branches in Cootehill and Belfast, which were likewise suppressed.[15]

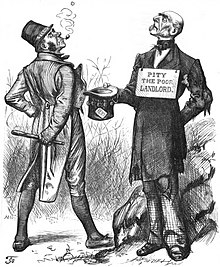

Socialists were not able to establish their own organisations again until the 1880s, in the context of the greater socialist revival happening around the United Kingdom. One early mention of an Irish connection to anarchism was the Boston-based Irish nationalist , who wrote articles for The An-archist in 1880 and 1881.[16] By this time, members of the Irish Home Rule movement led by Charles Stewart Parnell established the Irish National Land League, which spearheaded a period of agrarian agitation for land rights known as the Land War. The implementation of the Coercion Act to suppress the movement triggered the formation of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), which quickly developed into the first nation-wide socialist organisation in the United Kingdom. By December 1884, attempts were being made to form an Irish branch of the SDF by a local socialist club in Dublin, which on 18 January 1885 established the Dublin Democratic Association (DDA) "to promote and defend the rights of labour, and to restore the land to the people," although this did not affiliate with the SDF due to worries that it would alienate Catholic members of the Irish National League. Only about one quarter of the DDA's members were actually socialists, the rest being a mix of various different radical tendencies, the largest of which were nationalist Land Leaguers. Largely the organisation focused on promoting "the advancement of democratic principles", but after a foreign Marxist was invited to speak at the club, nationalist members protested, causing a split in the DDA that resulted in its disbandment by May 1885.[17]

By this time there had been a split within the SDF, in which libertarian socialists led by William Morris and Andreas Scheu broke from Henry Hyndman's parliamentarian faction, establishing the Socialist League with the intention of fomenting a social revolution. From its outset the League lent its support to the Home Rule movement, with its secretary John Lincoln Mahon setting into motion efforts to recruit Irish members to the League. By June 1885, the League's , an English anarchist, had moved to the North Strand in Dublin, where he distributed the League's newspaper Commonweal.[18][19] Despite a sense of pessimism regarding the prospects of propagating socialism in Ireland, in December 1885, Gabriel was able to establish a branch of the Socialist League in Dublin, drawing its membership from a number of former members of the DDA and even a couple former members of the IWA. The anti-parliamentarism and atheism proclaimed by the League quickly made the rounds at the local socialist club, in spite of the impediment provided by the prevailing religious orthodoxy in Ireland. The Dublin League remained a small organisation throughout its existence, with few more than 20 members, but still managed to successfully propagate socialism for the first time in Ireland. At the first meeting of the Dublin branch, which attracted 60 people, the young Irish anarchist Thomas Fitzpatrick railed against Irish nationalism in favour of internationalism, arguing against Home Rule but without providing a socialist alternative (one which would only later be provided by James Connolly).[20][21] The Irish Socialist League's opposition to Home Rule came largely from its anarchist rejection of parliamentarism, with Gabriel arguing that "the power of one man to govern another should be swept away under the socialist system."[22][23]

Unlike its predecessors, the activities and meetings of the Socialist League were able to continue largely unmolested until April 1886, organising among local bottlemakers during a lockout and inviting William Morris to give lectures in the city. But with the defeat of the First Home Rule Bill, the organisation's capacities began to wane as political agitation in Ireland started to focus almost exclusively on the issue of Home Rule. By October 1886, the Dublin League had come into conflict with the London-based Central Council over the earlier expulsion of Charles Reuss, with the anarchist-leaning Dublin branch supporting Reuss in line with The Anarchist newspaper. The branch quickly resolved the dispute within a month, but members had already become discouraged by the conflict, and the Dublin League collapsed in March 1887. Nevertheless, former members of the League continued their socialist agitation for years to come, with the Socialist League being quickly succeeded by the National Labour League (NLL). The NLL mobilised the unemployed to demonstrate in the streets and proclaimed a distinctly revolutionary socialist outlook, calling for the common ownership of land and for Irish workers to rise up against capitalism. By the turn of the 1890s, new unionism was introduced to Ireland by the Irish Socialist Union, laying the foundations for the rise of syndicalism.[24][25]

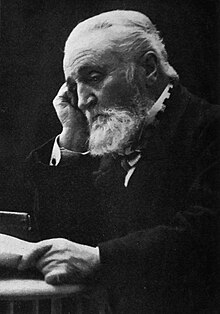

Around the same time, George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) wrote the article "What's in a name (how an anarchist might put it)" at the request of Charlotte Wilson for issue no. 1 of The Anarchist in 1885. Shaw had been taught French by the Communard Richard Deck, who introduced him to Proudhon. Later he was embarrassed by unauthorised reprints, as he was a Fabian socialist, not an anarchist.[citation needed] Irish writer Oscar Wilde notably expressed anarchist sympathies, especially in his essay The Soul of Man under Socialism.[26]

Around 1890 John Creaghe, an Irish doctor who was joint founder (with Fred Charles), of The Sheffield Anarchist, took part in the "no rent" agitation before leaving Sheffield in 1891. He went on to become the founding editor in Argentina of the anarchist paper, El Oprimido, which was one of the first to support the "organisers" current (as opposed to refusal to organise large scale organisations).[27] In 1892 English anarchists visited Fred Allen at the Dublin independent offices to see if his Fair Trial Fund could be used for anarchist as well as Irish Republican Brotherhood prisoners.[28] In 1894 at Trinity College Dublin's Fabian Society "over 200 students listened sympathetically" to a lecture on "Anarchism and Darwinism".[29]

Syndicalism[]

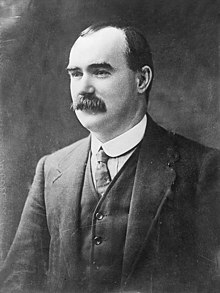

In 1896, the Irish syndicalist James Connolly[a] moved to Dublin, where he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP) with the aim of establishing an Irish workers' republic, but left the party in 1903 following an internal conflict with E. W. Stewart regarding trade unionism and electoralism. Connolly subsequently led the Scottish left-wing faction of the Social Democratic Federation to split off and form the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), a De Leonist political party that advocated for industrial unionism. He then moved to the United States, where he collaborated with fellow syndicalists in the American SLP and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), before returning to Ireland in 1908.[31][32]

Another Irish syndicalist that moved to Dublin at this time was James Larkin, a trade union activist of the Liverpool-based National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) that had been expelled for participated in wildcat strike actions. Connolly and Larkin together collaborated in the foundation of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU), a trade union with syndicalist tendencies which the two hoped would eventually form the nucleus of "One Big Union" in Ireland.[31] Connolly's view of syndicalism held that "the political, territorial state of capitalist society will have no place or function under Socialism", thus he rejected the use of state bureaucracy in the transition to socialism, instead considering that industrial unions would provide the framework for a future socialist society.[33] Connolly also viewed electoral participation as a "political weapon" for industrial unionists, although he rejected the conquest of state power as a goal, believing that any social revolution must immediately abolish the state.[34] This position led Connolly and Larkin to establish the Labour Party as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress (ITUC), of which the ITGWU was an affiliate.[31]

A series of industrial disputes led by the ITGWU eventually escalated into the Dublin lock-out of 1913. During the lockout, Connolly and Larkin came together with Jack White to establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), a workers' militia set up to protect striking workers from the police. Following the suppression of the strike movement, Larkin fled to the United States, where he became involved in the activities of the IWW and later gravitated towards Bolshevism.[31] Meanwhile, with the outbreak of World War I, a section of the ICA around Connolly began to plan for an armed uprising against British rule with the aim of establishing an independent Irish Republic. Connolly's take on republicanism rejected nationalism, which he believed would simply lead to Irish workers being oppressed by an Irish capitalist state. Connolly insited on the necessity for Irish independence to come about through a socialist revolution in which workers would seize the means of production, stating that "only the Irish working class remain as the incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland." But by 1916, Connolly had shelved his anti-nationalist criticisms and socialist ambitions, leading the ICA into an alliance with Irish nationalists. During the Easter Rising, republican forces including the ICA seized a number of strategically important buildings around Dublin and a Provisional Government including Connolly proclaimed the formation of an Irish Republic, before its suppression by British forces and the unconditional surrender of the rebels. Connolly and the other rebel leaders were executed in the weeks following. In his analysis of the Rising, The Only Hope of Ireland, the Russian anarcho-communist Alexander Berkman declared that it had failed because of its nationalist character and lack of socialist program:[35]

"The precious blood shed in the unsuccessful revolution will not have been in vain if the tears of their great tragedy will clarify the vision of the sons and daughters of Erin and make them see beyond the empty shell of national aspirations toward the rising sun of the international brotherhood of the exploited in all countries and climes combined in a solidaric struggle for emancipation from every form of slavery, political and economic"

Following the Irish War of Independence, Jack White had found himself politically isolated from the main camps of the new Irish Free State, gravitating towards anti-parliamentary communism and briefly joining Sylvia Pankhurst's Workers Socialist Federation. In 1934, a number of communist members of the Irish Republican Army came together with other left-wing figures to establish the Republican Congress, which White joined, organising a branch in Dublin with other former British Army serviceman. The Congress soon experienced a split between socialists in favour of establishing a workers' republic and communists that advocated a temporary alliance with Fianna Fail, with the socialists breaking off and many joining the Labour Party, while White himself remained in the organisation. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, the Congress organised support for the Republicans and established the Connolly Column, with White joining it to fight against the Nationalists. Upon arriving in Spain, White was immediately impressed by the revolutionary gains, particularly the collectivisation projects and the organisation of the confederal militias advanced by the anarchists. While fighting on the Aragon front, White trained militiamen and women how to use firearms, while also becoming increasingly dissilusioned with the influence of the Communist Party over the Irish internationalists, gravitating closer towards anarchism. White began to clash with Irish Marxist-Leninists like Frank Ryan, enough so that he relinquished command in the International Brigades and joined the anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labor (CNT). Back in London he worked with Emma Goldman and the Freedom newspaper to organise support for the Spanish anarchists, but following the Nationalist victory in the civil war and the subsequent Allied victory in World War II, White died in 1946, leaving behind a number of papers that his family destroyed out of shame.[36]

Later developments in Irish syndicalism included the establishment of the Congress of Irish Unions after a split in the ITUC, their subsequent merger into the Irish Congress of Trade Unions and eventually the merger of the ITGWU and Larkin's Workers' Union into the Services, Industrial, Professional and Technical Union (SIPTU), which continues its activities to this day as Ireland's largest trade union.

Modern development[]

In the late 1960s, as the civil rights campaign took off, People's Democracy, before it became a small Trotskyist group, included some self-described anarchists[37] such as John McGuffin and Jackie Crawford. The latter was one of the group who sold Freedom in Belfast's Castle Street in the late 1960s. There was an anarchist banner on the Belfast-Derry civil rights march.[38] PD members, including John Grey, contributed to a special issue of the British Anarchy Magazine about Northern Ireland in 1971.

In the early 1970s some ex-members of the Official IRA became interested in anarchism and developed contact with Black Flag magazine in London. Among names used were Dublin Anarchist Group and New Earth. Their existence was brief and not widely known.[39] A number of jailings for "armed actions" saw the group disappear. Two members, Marie and Noel Murray, were later sentenced to death for the killing of an off-duty Garda during a bank raid as part of a group called the Anarchist Black Cross (with no relation to the much older prisoner support group). Their sentences were commuted to life imprisonment on appeal. In 1970 there existed a hippy commune in a squatted house on Dublin's exclusive Merrion Road known as the Island Commune. Some inhabitants, including Ubi Dwyer of Windsor Free Festival fame, sold Freedom outside the GPO on Saturdays.

Origins of the modern movement[]

The first steps towards building a movement came in the late 1970s when a number of young Irish people who had been living and working in Britain returned home, bringing their new-found anarchist politics with them. Local groups were set up in Belfast, Dublin, Limerick, Dundalk and Drogheda. Over the next decade anarchist papers appeared, some for just one or two editions, others with a much longer life. Titles included Outta Control (Belfast), Anarchist Worker (Dublin), Antrim Alternative (Ballymena), Black Star (Ballymena), Resistance (Dublin) and Organise! (Ballymena). Bookshops were opened in Belfast (Just Books in Winetavern Street) and Dublin (ABC in Marlborough Street). All of these groups attracted people who identified themselves as anarchists but had little in the way of agreed politics or activities, and no organised discussions or education about anarchism. This imposed limits to what they could achieve and even to their continued existence – all groups were short-lived, had little impact and left no lasting legacy.

In 1978, ex-members of the Belfast Anarchist Collective and the Dublin Anarchist Group decided that a more politically united, class-based, and public organisation was necessary. Their discussions led to the Anarchist Workers Alliance, which existed from 1978–81, although only to any substantial extent in Dublin.[39] It produced Anarchist Worker nos. 1–7; documents on the national question, women's liberation, trade unions, and a constitution.

Irish anarchists, amongst others, organised Reclaim the Streets parties in Dublin in 2002 and 2003.[40] In 2004 Dublin Grassroots Network, a “broad-based network including anarchists, environmentalists, anti-war activists”,[41] organised protests against the May 2004 summit of European heads of government in Farmleigh.[42] During the protests there were clashes between demonstrators and police.[42] 29 people were arrested and there were several injuries.[42]

Modern conception of Irish anarchism[]

Ireland has seen a relatively large comparative growth in anarchist politics in various forms since the alter-Globalisation movement of the 1990s and 2000s. Dublin now hosts numerous explicitly anarchist squats, as well as regular social events facilitating for the anarchist scene in various locations. Irish anarchists have been involved in activities such as squatting and anti-fascist action, and have been active within the pro-choice and anti water charge movements.

Active organisations[]

Several organisations have operated in Ireland in the past:

- The Workers Solidarity Movement was a platformist anarchist group that had members in Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Belfast, Derry, and Galway. It formed in 1984.

- A Belfast branch of the British Solidarity Federation, which was formerly Organise!, a small class struggle anarchist organisation formed in 2003 from a merger of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Federation, Anarchist Federation, Anarchist Prisoner Support and a number of individuals.

- The Dublin-based Revolutionary Anarcha-Feminist Group (RAG), a group for female anarchists was formed in 2005 and has published six issues of a magazine, The Rag.

- In April 2015, the Dublin Anarchist Black Cross (ABC) was founded.[43]

There are also a number of organisations and spaces which, while perhaps not explicitly anarchist, share much in common with the anarchist movement. These include the Grassroots Gatherings (2001–present), the Dublin Grassroots Network (2003–2004), Grassroots Dissent (2004–), Galway Social Space (2008–2010), Rossport Solidarity Camp (2005–2014), Jigsaw (2015-2021) formerly titled Seomra Spraoi (2004–2015), 'Grangegorman' Squat (2013-2015) and the (2015–2016).

See also[]

- World Socialist Party (Ireland) - defunct political party which advocated a stateless, democratic society and rejected the idea of vanguardism and any transitional state.

- Squatting in Ireland - Often linked to Irish Anarchist organisations

Notes[]

- ^ In the book Black Flame, Lucien van der Walt argued that Connolly, despite being a Marxist syndicalist, "should be considered part of the broad anarchist tradition."[30]

References[]

- ^ "WSM has come to an end - we look forward to new anarchist beginnings". Workers Solidarity Movement. 8 December 2021.

- ^ Peden 1971, p. 3.

- ^ Peden 1971, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Rothbard 2006, p. 282.

- ^ Peden 1971, p. 4.

- ^ Peden 1971, pp. 4, 8.

- ^ Peden 1971, p. 8.

- ^ Rothbard 1958, p. 114.

- ^ Rothbard 1958, p. 117.

- ^ Rothbard 1958, pp. 114–118.

- ^ Sobran 2002.

- ^ Smith 2014.

- ^ Flood 2007, pp. 2–17.

- ^ Flood 2007, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Lane 1997, p. 19.

- ^ Becker 1988, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Lane 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Lane 1997, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Lane 1997, p. 21.

- ^ Lane 2008, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Lane 1997, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Lane 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Lane 2008, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Goodway 2006, pp. 62–92.

- ^ Ó Catháin 2004.

- ^ McGee 2005, p. 216.

- ^ McGee 2005, p. 218.

- ^ van der Walt & Schmidt 2009, pp. 149, 164, 170.

- ^ a b c d van der Walt & Schmidt 2009, p. 163.

- ^ O’Connor 2010, p. 194.

- ^ van der Walt & Schmidt 2009, pp. 163–164.

- ^ van der Walt & Schmidt 2009, p. 164.

- ^ van der Walt & Schmidt 2009, p. 318.

- ^ MacSimóin 1997.

- ^ Hall 2019, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Hall 2019, p. 5.

- ^ a b Goodwillie 1983.

- ^ McCarthy, Dec. "'Looking back on the Dublin EU summit protests - Mayday 2004'". anarkismo.net. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Looby, Robert. "'May Day Smear Campaign – the Irish media turns against protesters.'". Three Monkeys Online. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "'Protest group blames gardaí for clashes'". 'Raidió Teilifís Éireann'. 2 May 2004. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Introducing the Dublin Anarchist Black Cross". dublinabc.ana.rchi.st. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Becker, Heiner (October 1988). "The Mystery of Dr Nathan-Ganz". The Raven. London: Freedom Press (6): 118–145. ISSN 0951-4066. OCLC 877379054.

- Flood, Andrew (2007). The Rising of the Moon. Dublin: Workers Solidarity Movement.

- Goodway, David (2006). "Oscar Wilde". Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 62–92. ISBN 1-84631-025-3. OCLC 897032902.

- Goodwillie, John (1983). "Glossary of the Left in Ireland 1960–83". Gralton Magazine. Dublin: Gralton Co-operative Society (9). ISSN 0332-4443. OCLC 1235535966. Archived from the original on 25 August 2009.

- Hall, Michael (October 2019). A History of the Belfast Anarchist Group and Belfast Libertarian Group (PDF). Island Pamphlets. Newtownabbey: Island Publications. pp. 3–4. OCLC 1280067425. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- Lane, Fintan (1997). "The Emergence of Modern Irish Socialism 1885-87". Red & Black Revolution. Dublin: Workers Solidarity Movement (3): 19–22. OCLC 924048574.

- Lane, Fintan (2008). ""Practical anarchists, we": social revolutionaries in Dublin, 1885–87". History Ireland. Dublin: History Ireland Ltd. 16 (2): 16–21. ISSN 0791-8224. JSTOR 27725765. OCLC 231619350.

- MacSimóin, Alan (1997). "Jack White: Irish Anarchist who organised Irish Citizens Army". Workers Solidarity. Dublin: Workers Solidarity Movement (50). OCLC 51859611.

- McGee, Owen (2005). The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood, from the Land League to Sinn Féin. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 1851829725. OCLC 238617973.

- Ó Catháin, Máirtín (2004). "Dr. John O'Dwyer Creaghe (1841-1920)". Irish Migration Studies in Latin America. Waterford: Society for Irish Latin American Studies. ISSN 1661-6065. LCCN 2010065894. OCLC 1074613522.

- O’Connor, Emmet (2010). "Syndicalism, Industrial Unionism, and Nationalism in Ireland". In Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (eds.). Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940. Studies in Global Social History. 6. Leiden: Brill. pp. 193–224. ISBN 9789004188495. OCLC 868808983.

- Peden, Joseph R. (April 1971). "Stateless Societies: Ancient Ireland". The Libertarian Forum. New York: Mises Institute. III (4): 3–4, 8. ISBN 1-933550-02-3. ISSN 0047-4517. OCLC 8546937.

- Rothbard, Murray (January 1958). "A Note on Burke's Vindication of Natural Society". Journal of the History of Ideas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 19 (1): 114–118. doi:10.2307/2707957. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2707957. OCLC 1027084093. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- Rothbard, Murray (2006) [1973]. For a New Liberty. Auburn: Mises Institute. ISBN 978-0-945466-47-5. OCLC 75961482.

- Smith, George H. (21 March 2014). "Edmund Burke, Intellectuals, and the French Revolution, Part 2". Libertarianism.org. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- Sobran, Joseph (24 January 2002). "Anarchism, Reason, and History". The Real News of the Month. Griffin Communications. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- van der Walt, Lucien; Schmidt, Michael (2009). Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-16-1. LCCN 2006933558. OCLC 1100238201.

Further reading[]

- Ó Catháin, Máirtín (2012) [2004]. A Wee Black Book of Belfast Anarchism (1867-1973) (PDF) (2nd ed.). Belfast: Organise!. OCLC 1194693455.

- White, Jack (2005) [1930]. Misfit: An Autobiography (2nd ed.). Dublin: Livewire publications. ISBN 1905225202. OCLC 70220211.

External links[]

- Anarchism in Ireland

- Anarchism by country

- Political movements in the Republic of Ireland