Andrew Jackson Downing

Andrew Jackson Downing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 31, 1815 |

| Died | July 28, 1852 (aged 36) Hudson River, New York, US |

| Resting place | Cedar Hill Cemetery, Newburgh, New York |

| Occupation | Landscape gardener (later to be called landscape architect), horticulturist |

| Known for | Contributions to Gothic Revival architecture, first major American landscaper |

| Style | Carpenter Gothic, Gothic Revival, Italianate |

| Spouse(s) | Caroline DeWint Downing (1815–1905) |

Andrew Jackson Downing (October 31, 1815 – July 28, 1852)[1] was an American landscape designer, horticulturist, and writer, a prominent advocate of the Gothic Revival in the United States, and editor of The Horticulturist magazine (1846–52). Downing is considered to be a founder of American landscape architecture.

Early life[]

Downing was born in Newburgh, New York to Samuel Downing, a wheelwright and later nurseryman, and Eunice Bridge. After finishing his schooling at sixteen, he worked in his father's nursery in the Town of Newburgh, and gradually became interested in landscape gardening and architecture. He began writing on botany and landscape gardening and then undertook to educate himself thoroughly in these subjects. He married Caroline DeWint, daughter of John Peter DeWint, in 1838.[2]

Professional career[]

His official writing career started when he began producing articles for various newspapers and horticultural journals in the 1830s. In 1841 his first book, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, was published to a great success; it was the first book of its kind published in the United States.[3]

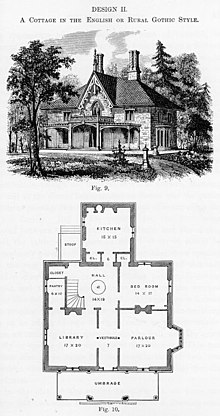

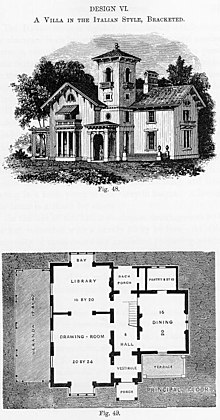

In 1842 Downing collaborated with Alexander Jackson Davis on the book Cottage Residences, a highly influential pattern book of houses that mixed romantic architecture with the English countryside's pastoral picturesque, derived in large part from the writings of John Claudius Loudon.[4] The book was widely read and consulted, doing much to spread the so-called "Carpenter Gothic" and Hudson River Bracketed architectural styles among Victorian builders, both commercial and private.

In this very early stage of his career, Downing also engineered landscapes and provided horticultural makeovers to patrons throughout the Northeast. He also designed at least two houses, including one for his friend John J. Monell in Newburgh completed about 1842. Though somewhat altered today, the Monell House showed Downing's taste for Italianate motifs in addition to exteriors that harmonized with their setting. [5]

With his brother Charles, he wrote Fruits and Fruit Trees of America (1845), long a standard work. In the early 1850s, Downing called the "Jonathan's Fine Winter" apple the "Imperial of Keepers", which led to it being renamed the York Imperial apple.[6][7] This was followed by The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), a revolutionary and influential pattern book that marked he end of his collaboration with Davis. Completing extensive drawings for interiors and furniture, Davis's talents as an artist engaged readers and served as early reference guides for homeowners to decorate their own spaces without hiring additional designers. [8]

By the mid-1840s Downing's reputation was impeccable and he was, in a way, a celebrity of his day. This afforded him a friendship with Luther Tucker— publisher and printer of Albany, New York – who hired Downing to edit a new journal. "The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste" was first published under Downing's editorship in the summer of 1846; he remained editor of this journal until his death in 1852. The journal was his most frequent influence on society and operated under the premises of horticulture, pomology, botany, entomology, rural architecture, landscape gardening, and, unofficially, premises dedicated public welfare in various forms. It was in this journal that Downing first argued for a New York Park, which in time became Central Park. It was in this publication that Downing argued for state agricultural schools, which eventually gave rise. And it was here that Downing worked diligently to educate and influence his readers on refined tastes regarding architecture, landscape design, and even various moral issues.

In 1850, as Downing traveled to England, an exhibition of continental landscape watercolors by Englishman Calvert Vaux captured his attention. He encouraged Vaux to emigrate to the United States, and opened what was to be a thriving practice in Newburgh. Frederick Clarke Withers (1828–1901) joined the firm during its second year. Downing and Vaux worked together for two years, and during those two years, he made Vaux a partner. Together they designed many significant projects, including the grounds in the White House and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. Vaux's work on the Smithsonian inspired an article he wrote for The Horticulturist, in which he stated his view that it was time the government should recognize and support the arts.

In 1846, the Smithsonian Institution was established, and soon a building to house the new institution was started on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. James Renwick's Norman-style building stimulated a move to landscape the Mall in a manner consistent with the romantic character of the Smithsonian's building. President Millard Fillmore commissioned Downing to create a plan that would redeem the Mall from its physical neglect.

Downing presented his plan for the National Mall to the Regents of the Smithsonian Institution on February 27, 1851. The plan was a radical departure from the geometric, classical design for the Mall that Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant had placed in his 1791 plan for the future federal capital city (see L'Enfant Plan).[9] Instead of L'Enfant's "Grand Avenue," Downing envisioned four individual parks, with connecting curvilinear walks and drives defined with trees of various types. Downing's objective was to form a national park that would serve as a model for the nation, as an influential example of the "natural style of landscape gardening" and as a "public museum of living trees and shrubs."[10][11]

President Fillmore endorsed two-thirds of Downing's plan in 1851, but Congress found it to be too expensive and released only enough funds to develop the area around the Smithsonian. In 1853, Congress cut off all funds so that the plan was never entirely completed.[12] However, federal agencies developed several naturalistic parks within the Mall over the next half century in accordance with Downing's plan.[11] The parks remained until replaced by features that the McMillan Plan of 1902 described (see History of the National Mall).[11]

In 1845, Downing was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician.

Architectural works with Vaux[]

Date circa 1857

- Joel T. Headley House, "Cedar Lawn," New Windsor, New York (1850–51)

- Matthew Vassar Cottage and gatehouse, "Springside," Poughkeepsie, New York (1850)[13]

- Robert P. Dodge House, Washington, DC (1850–53)[14]

- Francis Dodge House, Washington, DC (1850–53)

- William L. Findlay House, Newburgh, New York (1850–51), demolished

- David Moore House, Newburgh, New York (1851–52)[15]

- Dr. William A. M. Culbert House, Newburgh, New York (1851–52)

- Daniel Parish House, Newport, Rhode Island (1852)

Downing's philosophy[]

- People's pride in their country is connected to pride in their home. If they can decorate and build their homes to symbolize the values they hope to embody, such as prosperity, education and patriotism, they will be happier people and better citizens.

- "A good house will lead to a good civilization."

- The "individual home has a great value to a people."

- "There is a moral influence in a country home."

- A good home will encourage its inhabitants to pursue a moral existence.

Architectural influence[]

Downing's building designs were mostly for single family rural houses built in the Picturesque Gothic and Italianate styles. He believed every American deserved a good home, so he designed homes for three types: villas for the wealthy, cottages for working people and farmhouses for farmers

Downing believed that architecture and the fine arts could affect the morals of the owners, and that improvement of the external appearance of a home would help "better" all those who had contact with the home. The general good of America was benefited by good taste and beautiful architecture, he wrote. Downing saw that the family home was becoming the place for moral education and the focus of middle class America's search for the meaning of life.

Downing developed his view that country residences should fit into the surrounding landscape and blend with its natural habitat. He also believed that architecture should be functional and that designs for residences should be both beautiful and functional. In the beginning of his Architecture of Country Houses is a lengthy essay on the real meaning of architecture. He wrote that even the simplest form of architecture should be an expression of beauty, but the design should never neglect the useful for the beautiful. He went on to say that "(in) perfect architecture no principle of utility will be sacrificed to beauty, only elevated and ennobled by it." He considered landscape gardening and architecture to be an art.[16]

In Cottage Residences he published the designs for 28 houses; in addition to the house plans, the designs included the plans for laying out the gardens, orchards, grounds and even included various plants to be used. In his Architecture of Country Houses,[17] he included designs for cottages, farmhouses and villas and commented on interiors, furniture and even the best methods of warming and ventilating them. Some of his designs were very simple and affordable so that all classes of society could enjoy life outside the city. In his publication, he criticized the builders who borrowed architectural elements to imitate villa style in a cottage as having a poor taste. Examples of such were temple cottage where a portico with large wooden columns were added to a small cottage, cocked-hat cottage where many gables were added to fill the cottage roof, and improper use of ornamental parts such as using "gingerbread" look sawn-out thin board instead of a properly carved-out vergeboard.[18] His own residence, Highland Gardens, in Newburgh, New York, was quite large with meticulous grounds and many greenhouses with plants and trees from around the world brought to him by his whaling father-in-law.

Through the publication of his designs, he is credited with the popularization of the front porch. He saw the porch as the link from the house to nature. Building porches had just become easier due to the advance in building methods, and these two factors together resulted in the frequency of front porches being built on residences at that time. At the same time, many people were moving from the city to the surrounding countryside because of the advent of railroad and steamship transportation. Downing believed interacting with nature had a healing effect on mankind and wanted all people to be able to experience nature.

Early death[]

On July 28, 1852, Downing was traveling on the steamer Henry Clay with his wife and extended family. A fire broke out amidships when the ship was just south of Yonkers, New York, on the Hudson River. A boiler explosion quickly spread flames across the wooden vessel and Downing was killed along with 80 others.[19] A few ashen remains and his clothes were recovered days later.[20][21]

Downing's remains were interred first in Old Town Cemetery, but later transferred to Cedar Hill Cemetery, in his birthplace of Newburgh, New York.

Following Downing's death, Withers and Vaux took over his architectural practice. After his death, writer and friend Nathaniel Parker Willis referred to Downing as "our country's one solitary promise of a supply for [the]... scarcity of beauty coin in our every-day pockets. He was the one person who could be sent for... to look at fields and woods and tell what could be made out of them".[22]

Legacy[]

Downing influenced not only Vaux but also landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted; the two men met at Downing's home in Newburgh. In 1858, their joint design, the Greensward Plan, was selected in a design competition for the new Central Park in New York City. In 1860, Olmsted and Vaux proposed that a bust of Downing be placed in the new park as an "appropriate acknowledgment of the public indebtedness to the labors of the late A. J. Downing, of which we feel the Park itself is one of the direct results." The monument was never built in the park, but a memorial urn honoring Downing stands in the Enid A. Haupt Garden near the Smithsonian's "Castle" (see Andrew Jackson Downing Urn).[23]

Botanist John Torrey named the genus Downingia after Downing.

In 1889, the city of Newburgh commissioned a park design from Olmsted and Vaux. They accepted, on the condition that it be named after their former mentor. It opened in 1897, called "Downing Park". It was their last collaboration.

The most intact structure designed by Downing is his house for Joel T. Headley, "Cedar Lawn," in New Windsor, New York, one of his first collaborations with Vaux.[24] Other few surviving structures include the David Moore House and Dr. William A. M. Culbert House in Newburgh, however, both are highly altered or ruinous. Exemplifying his original vision is the gatehouse at Matthew Vassar's estate, "Springside" in Poughkeepsie, New York. The house and the estate's gardens designed by Downing are a National Historic Landmark. The nearby Cedarcliff Gatehouse is also believed to have been designed by him.[25]

Downing's wife and friends of the family put up a monument to Downing in the shape of an urn that was at his home in Newburgh. They inscribed on it words that he had written "Plant spacious parks in your cities, and loose their gates as wide as the morning, to the whole people."

Another of Andrew Jackson Downing's surviving structures in the Italianate style, the Robert Dodge House, still stands today in Georgetown, D.C., but stands significantly altered from when originally constructed. The Dodge House was an exact opposite of the Francis Dodge House aside from the windows, fenestration, and decorative ornaments.

C. Dodge Estate-Front Entry of House-Luther Briggs

Charles Charles Dodge Estate Italian Influence

Charles Dodge Estate Italian

Charles Dodge Estate Mansion

Robert Dodge Mansion

Francis Dodge Mansion

Francis Dodge Mansion

Selected works[]

- A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 1841.[26]

- Cottage Residences: or, A Series of Designs for Rural Cottages and Adapted to North America, 1842; reprinted as Andrew Jackson Downing, Victorian Cottage Residences, Dover Publications, 1981.[27]

- The Fruits and Fruit-trees of America: Or, The Culture, Propagation, and Management, in the Garden and Orchard, of Fruit-trees Generally : with Descriptions of All the Finest Varieties of Fruit, Native and Foreign, Cultivated in this Country, 1847[28]

- The Architecture of Country Houses: Including Designs for Cottages, and Farm-Houses and Villas, With Remarks on Interiors, Furniture, and the best Modes of Warming and Ventilating, D. Appleton & Company, 1850; reprinted as Andrew Jackson Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses, Dover Publications, 1969.[29]

- "On the Moral Influence of Good Houses". 2. Horticulturist. February 1818. pp. 345–47. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

References[]

- ^ {{cite web|url=https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Andrew_Jackson_Downing%7Cwebsite=History of Early American Landscape Design|accessdate=July 19, 2021

- ^ Schuyler, David (February 2000). "Downing, Andrew Jackson". American Council of Learned Societies: American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "History of Horticulture". Ohio State University. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson Downing". Fredericklawolmstead.com. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Downs, Arthur Channing. Downing and the American House. Newton Square, PA: The Downing & Vaux Society, 1988, 49.

- ^ "Apple Tree Descriptions". Barkslip's Micro-Nursery. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Marker Details: York Imperial Apple". Explore PA History. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Yglesias, Caren. The Complete House and Grounds: Learning From Andrew Jackson Downing's Domestic Architecture. Chicago: Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, 2011.

- ^ Note: L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life, while residing in the United States. He wrote this name on his "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ...." (Washington, D.C.) and on other legal documents. However, during the early 1900s, a French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant". (See: Bowling (2002).) The National Park Service identifies L'Enfant as Major Peter Charles L'Enfant and as Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant on its website. The United States Code states in 40 U.S.C. 3309: "(a) In General.—The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant."

- ^ (1) Schuyler, David (February 2000). "Downing, Andrew Jackson". American Council of Learned Societies: American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

In late 1850 Downing was commissioned to landscape the public grounds in Washington, D.C. This 150-acre tract extended west from the foot of Capitol Hill to the site of the Washington Monument and then north to the president's house. Downing saw this as an opportunity not simply to ornament the capital but also to create the first large public park in the United States. He believed that the Washington park would encourage cities across the nation to provide healthful recreational grounds for their citizens. Although only the initial stages of construction had been completed at the time of his death, Downing's commission, as well as the influence of his writings, merited the epithet "Father of American Parks."

(2) "Downing's Plan for the Mall". Smithsonian Gardens: The Downing Urn in the Enid A. Haupt Garden. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

(3) "Andrew Jackson Downing's Plan for the National Mall: Plan Showing Proposed Laying Out of the Public Grounds at Washington: Copied from the Original Plan by A. J. Downing: February. 1851. To Accompany the Annual Report dated October 1st, 1867, of Bvt Brig. Genl. N. Michler In Charge of Public Buildings, Grounds & Works". National Archives Catalog. Retrieved September 17, 2017. - ^ Jump up to: a b c (1) Hanlon, Mary. "The Mall: The Grand Avenue, The Government, and The People". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

(2) Sherald, James L. (December 2009). Elms for the Monumental Core: History and Management Plan (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center for Urban Ecology, National Capital Region, National Park Service. p. 3. Natural Resource Report NPS/NCR/NRR--2009/001. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2010. - ^ "The Unveiling of A. J. Downing's Victorian Plan for Washington, D.C., 1851," by Heather Wanser, Senior Paper Conservator, Conservation Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540.

- ^ Cottage demolished, gatehouse and landscape partly intact.

- ^ Exterior highly altered.

- ^ Interior highly altered, exterior well preserved.

- ^ Downing, Andrew Jackson (1950). The Architecture of Country Houses. New York: D. APPLETON & COMPANY. pp. 1–38.

- ^ Country Houses

- ^ Downing, Andrew Jackson (1852). The Architecture of Country Houses: Including Designs for Cottages, Farm Houses, and Villas, with Remarks on Interiors, Furniture, and the Best Modes of Warming and Ventilating. D. Appleton & Company. pp. 41–43. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Henry Clay disaster Archived March 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Henry Clay catastrophe; Removal of the Wreck. More missing passengers. Coroner's Inquest—Testimony of Mr. Radford. Interesting particulars. The Coroner's Inquest at Yonkers. The Dead. List of Passengers Missing. Particulars and Incidents." New York Times, August 4, 1852

- ^ "The Henry Clayu catastrophe; Trial of the Owners and Officers of the Henry Clay. Opening of the defendant's case. Testimony for the accused. United States Circuit Court." New York Times, October 29, 1853

- ^ Callow, James T. Kindred Spirits: Knickerbocker Writers and American Artists, 1807–1855. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1967: 216.

- ^ "DOWNING, Andrew Jackson: Urn on the east side of the Arts & Industries Bldg in Washington, D.C. by Robert E Launitz, Calvert Vaux". dcMemorials.com. 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Borgeson, Hannah. “‘A Cottage in the Rhine Style’: A Downing and Vaux Residential Design in New Windsor, New York” Master’s thesis, City College of the City University of New York, 2003.

- ^ Townley McElhiney Sharp (August 1980). "National Register of Historic Places Registration:Cedarcliff Gatehouse". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ Downing, A. J. (Andrew Jackson). "A treatise on the theory and practice of landscape gardening, adapted to North America; with a view to the improvement of country residences. Comprising historical notices and general principles of the art, directions for laying out grounds and arranging plantations, the description and cultivation of hardy trees, decorative accompaniments to the house and grounds, the formation of pieces of artificial water, flower gardens, etc. with remarks on rural architecture .. (1841)". Landscape gardening; Architecture, Domestic. New York & London, Wiley and Putnam; Boston, C. C. Little & co. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Downing, A. J. (Andrew Jackson). "Cottage residences, or, A series of designs for rural cottages and cottage villas, and their gardens and grounds: adapted to North America (1842)". Architecture, Domestic; Cottages. New York : Wiley and Putnam. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Fruits-and-Fruit-Trees-of-America

- ^ Downing, A. J. (Andrew Jackson) (1861). "The architecture of country houses". Architecture, Domestic. New-York, D. Appleton & co. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

Sources[]

- Charles E. Beveridge and David Schulyer, eds., Creating Central Park, 1857–1861.

- David Schuyler, Apostle of Taste: Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815 — 1852.

- Judith K. Major, To Live in the New World: A. J. Downing and American Landscape Gardening, MIT Press, 1997.

- Rosenzweig, Roy & Blackmar, Elizabeth (1992). The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9751-5.

- Kris A. Hansen, Death Passage on the Hudson: The Wreck of the Henry Clay, Purple Mountain Press, October 2004. ISBN 1-930098-56-1; ISBN 978-1-930098-56-5.

- Sean T. Wright, Railroad and Suburb Development Historian. Descendant of the Nathan Carruth Family and Frank L. Wright Family.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Andrew Jackson Downing. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1900 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about Andrew Jackson Downing. |

- American landscape and garden designers

- American garden writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American horticulturists

- American architecture writers

- Gothic Revival architects

- 1815 births

- 1852 deaths

- People from Newburgh, New York

- Deaths due to ship fires

- Deaths from fire in the United States

- Accidental deaths in New York (state)

- Carpenter Gothic architecture in the United States

- American designers