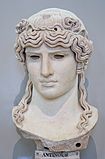

Antinous Mondragone

| Antinous Mondragone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Year | c. 130-138 AD. |

| Type | White marble |

| Dimensions | 95 cm (37 in) |

| Location | Louvre, Paris |

The Antinous Mondragone is a 0.95 m high marble example of the Mondragone type of the deified Antinous. This colossal head was made sometime in the period between 130 AD to 138 AD and then is believed to have been rediscovered in the early 18th century, near the ruined Roman city, Tusculum.[1][2] After its rediscovery, it was housed at the Villa Mondragone as a part of the Borghese collection, and in 1807, it was sold to Napoleon Bonaparte; it is now housed in the Louvre in Paris, France.[2]

This acrolithic sculpture was produced during the rule of Emperor Hadrian, who ruled from 117 AD until he died in 138 AD. It is widely accepted that Hadrian had kept Antinous as his lover and that they had a sexual relationship. However, this relationship did not accumulate much documentation, so a great deal of the details are left unknown. As a result of this, there are now many theories surrounding the subject of their relationship as well as the controversial death of Antinous in 130 AD.[1]

This sculpture was produced as one of many pieces of art made within the cult of Antinous, a cult that is accepted to have formed out of the grief Hadrian harnessed over the death of Antinous.[1] Out of the three distinct types of Antinous cult statues, this piece falls under the Mondragone type, which can be identified by the unique hairstyle that works as a reference to the Greek god, Dionysus.[3]

Subject[]

Antinous and Hadrian[]

Antinous was a young boy from Bithynium (Claudiopolis), Bithynia, and since early on in his life he was brought to Imperial Rome, there is not much information on his life or family from before.[4] The first meeting of Antinous and Hadrian has incited many theories; there are many rumors and assumptions about the many ways their paths may have crossed before records show them being together. However, it is widely acknowledged that Hadrian’s relationship with Antinous did not begin until Antinous was in his mid-to-late teenage years. In Greek terms, their relationship was of a pederastic nature; this would be a sexual relationship between an adult man and a boy in his teenage years. In terms of Roman ideals, there was no issue with a relationship between two men, as long as one of the men was not a fellow Roman citizen.[5] Going by the many depictions of Antinous, historians have concluded him to have been around 18 to 20 years of age around his death, therefore, being born around 110 to 112 AD.[6]

The story of Antinous’ death in 130 A.D. is dubious at best, there is no concrete story for his death, and there is no shortage of speculation around the topic.[1] However, the most widely accepted is that he drowned at the Nile River, as told by Hadrian, although there is much talk of sacrifice surrounding the topic, willing self-sacrifice by Antinous for the sake of Hadrian, or forced sacrifice of Antinous by Hadrian.[1] Overall, the speculation on this particular topic is expansive.[1]

Cult of Antinous[]

This cult was lively and enduring, even more so than Hadrian’s imperial cult. It was also more widespread, as shown by the fact that Antinous’ image is one of the most renowned in antiquity.[7] His image is also one of the most identified in classical antiquity, along with emperors Hadrian and Augustus.[3] It centered around Alexandria and Asia Minor, but there are traces of Antinous’ veneration or influence, even in places like the coast of North Africa. Antinoöpolis, Egypt was where the chief cult of Antinous can be seen; there were two temples built for his veneration here.[7] There were many places where he had substantial cults that possessed temples and priesthoods, some were at Hermopolis, Oxyrhynchus, and Tebtynis.[7] There were at least thirteen cities that honored Antinous on mainland Greece, and over in the Peloponnese, there were groups of worship scattered throughout this region.[7] In Mantineia, Antinous was considered to be a local god of sorts, and they had two temples to show for their veneration of him.[7] Athens has been found to have had at least four sculptures, among many other forms to give their devotion to the god Antinous.[7] The birthplace of Antinous, Bithynia, located in Asia Minor, was where one of the largest and the most vigorous cult was based.[7] In Asia Minor, there were around 27 known cities that have evidence of honoring the god Antinous, places such as Smyrna, Nikomedia, and Taros.[7] In the area that is known as modern Italy today, there is known to have been at least ten areas that expressed some type of worship for Antinous, as solid evidence, there has been evidence of seven temples in his honor here.[7] Furthermore, this area is where the Mondragone head was found, near the Roman city, Tusculum in the 18th century.[2] This widespread use of the god, Antinous' image proves to have aided in some type of union or collaboration of the Greco, Roman, and Egyptian Empires.[7]

Description[]

This sculpture can be identified as Antinous from the striated eyebrows, full pouting lips, somber expression, and the head's twist down and to the right (reminiscent of that of the Lemnian Athena), whilst its smooth skin and elaborate, center-parted hair mirror those of Hellenistic images of Dionysus (his Roman equivalent being Bacchus) and Apollo.[8][9][10][11] In reference to Dionysus, the side locks of hair that are seen on either side of this Antinous head can also be found on Dionysus, furthering a connection between the two through hairstyle.[8] The ancient geographer, Pausanias, was the only writer who provided some type of iconographic ‘pointers’ towards the understanding of Antinous art, and he found that there were similarities in some figures of Antinous, such as the Antinous of Mantineia, and Dionysus.[3]

The Mondragone head formed part of a colossal acrolithic cult statue for the worship of Antinous as a god. Acrolithic statues were made using a technique in which artists used a combination of wood and some type of stone to construct their sculptures.[12] In the case of the Antinous Mondragone, marble was the stone of choice. Per the technique, the marble would have only been used where body parts were visible, in places such as the head where the marble would be depicting their flesh.[12] Whereas the wood would have been used to craft the clothed portions of the statue.[12] This technique is said to have been used more often in areas where the cost of fine materials, such as marble, may have been too costly or not readily available.[12]

Thirty-one holes in three different sizes have been drilled for the attachment of a garland of some type (possibly made of ivy or vine leaves) in metal.[8] This head decoration is argued to have been some sort of tainia, a part of costume dress that would be worn around the head by the Greeks during festivals, and could also be shown worn in cult images.[8] The sculpture's eyes have been lost, however, they are thought to have been made in either bronze, ivory, or some type of colored stone.[11]

Style[]

Most art of Antinous can be categorized into one of the three distinct styles; the Main type, the Egyptianizing type, or the Mondragone type.[3] The Main type includes two variants; variant A and variant B, both of which can be differentiated by looking at the arrangement of the locks of hair on the forehead.[3][9] Art historian Caroline Vout argues that the use of the ‘lock-scheme’ method, in regards to the Main type, is not a sure way to conclude whether or not a piece should be disqualified from a certain type, but it would be a large contributing factor.[9] The Egyptianizing type, much like the Mondragone type, helps get across the idea that there was no sole model for the cult image of Antinous.[3] The Egyptianizing type is visually obvious in iconography as influenced or made in Egypt; the Antinous at Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli is an example of this particular style.[3] While all three types have iconographic differences, many of the depictions of Antinous are influenced by, or use iconography from youthful gods, such as Dionysus. Vout argues that without those iconographical borrowings, the cult image of Antinous would consist of just another pretty boy in Imperial Rome.[3]

Provenance[]

In 1618–1619, the gallery of Palazzo Mondragone began implementing pedestals for the displayed antiquities, including their colossal busts.[2] These busts were displayed in pairs of male and female figures that often brought disagreement with them in terms of who they were depicting; the male figure that was assumed to be a depiction of Julius Caesar was replaced by the Mondragone figure after its recovery from the earth.[2] It is said to have been found near Tusculum, specifically at Frascati between 1713 and 1729 and was certainly displayed as part of the Borghese collection at their Villa Mondragone there.[2] However, these dates have been argued against on the basis that the Antinous head was recorded as being seen in the gallery decades before in 1687 by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, a Swedish architect that had visited the villa.[2]

In 1807, it was bought with a large part of the Borghese collections for Napoleon; the Antinous head being sold for one of the highest prices out of the entire collection.[2] Sometime after this, a brown layer of wax was added to give an opaque finish, along with plaster around the base of the neck to make the statue look more complete – these were both removed in recent cleaning. It is now held at the Louvre Museum, though it toured to the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds in 2006 for the exhibition "Antinous: The Face of the Antique",[13][11] and returned to the United Kingdom for the British Museum's exhibition "Hadrian: Empire and Conflict" in 2008.

Scholarly interpretation[]

The 18th-century art historian, Johann Winckelmann made it better known by praising it in his History of Ancient Art, calling it "the glory and crown of art in this age as well as in others" and "so immaculate that it appears to have come fresh out of the hands of the artist".[14] This was since, though Roman in date, it echoed the 5th century BC Greek style which Winckelmann preferred over Roman art.[15]

Gallery[]

Statue of Antinous as Osiris (131–138 AD) as an example for the Egyptianizing type.

Statue of Antinous Farnese (130–137 AD) as an example of the Main type.

Statue of Antinous Mondragone (130–138 AD) as an example of the Mondragone type.

See also[]

- Antinous Farnese

- Capitoline Antinous

- Statue of Antinous (Delphi)

- Townley Antinous

Notes[]

- ^ a b c d e f Antinous, the lover of Emperor Hadrian, drowned in the Nile that year. Can be read about in: Lambert, Royston (1984). Beloved and God. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 128–142.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ehrlich, Tracy L. (2002). Landscape and Identity in Early Modern Rome: Villa Culture at Frascati in the Borghese Era. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 0 521 59257 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vout, Caroline (2005). "Antinous, Archaeology and History". The Journal of Roman Studies. 95: 80–96 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Lambert, Royston (1984). Beloved and God. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 15.

- ^ Vout, Caroline (2007). Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 53.

- ^ Lambert, Roytson (1984). Beloved and God. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lambert, Royston (1984). Beloved and God. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c d Perry, Walter Copland (1882). Greek and Roman Sculpture: A Popular Introduction to the History of Greek and Roman Sculpture. London: Longmans, Green. pp. 662–663.

- ^ a b c Kleiner, Diana E.E. (1992). Roman Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 243.

- ^ Vout, Caroline (2007). Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b c Vout, Caroline (2006). Antinous: the face of the Antique. Leeds: Henry Moore Institute. p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Grossman, Janet Burnett (2003). Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone : a Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 3.

- ^ Exhibition page Archived 2007-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ In the posthumous publication of Winckelmann's history translated into Italian with copious notes by Carlo Fea, Storia delle arti del disegno presso gli antichi Rome, 1783-84, it was described in vol. II, p 386, noted by Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900 (Yale University Press) 1981, p. 101.

- ^ In contrast to Winckelmann's enthusiasm for it, John Addington Symonds criticised the head in 1879 for its "vacancy and lifelessness".

Sources[]

Ehrlich, Tracy L. Landscape and Identity in Early Modern Rome : Villa Culture at Frascati in the Borghese Era. Cambridge, U.K. ;: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Grossman, Janet Burnett. Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone : a Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.

Kleiner, Diana E. E. Roman Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Lambert, Royston. Beloved and God : The Story of Hadrian and Antinous. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1984.

Perry, Walter Copland. Greek and Roman Sculpture: A Popular Introduction to the History of Greek and Roman Sculpture. London: Longmans, Green, 1882.

Vout, Caroline. “Antinous, Archaeology and History.” The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 95. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: Cambridge University Press. 2005, pp. 80–96, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20066818. Last accessed 1 November 2021.

Vout, Caroline. "Antinous: Face of the Antique" (exhibition catalogue, 2006), p. 80-81.

Vout, Caroline. Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mondragone Antinous. |

- (in French) Louvre database entry

- (in English) Photo repertory of Antinous types, for comparison

- Louvre Collections: Antinous Mondragone

- 2nd-century Roman sculptures

- Borghese antiquities

- Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures of the Louvre

- Antiquities acquired by Napoleon

- Sculptures of Antinous

- Archaeological discoveries in Italy

- Cult images