Architecture of Mesopotamia

Top: Mosaic panel (using stone cones) decorating a wall of one of the temple at the city of Uruk (Iraq), 2nd half of the 4th millennium BC, in the Iraq Museum (Baghdad); Centre: The Ziggurat of Ur, approximately 21st century BC, Tell el-Muqayyar (Dhi Qar Province, Iraq); Bottom: Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate (circa 575 BC) in the Pergamon Museum | |

| Years active | 10th millennium-6th century BC |

|---|---|

The architecture of Mesopotamia is ancient architecture of the region of the Tigris–Euphrates river system (also known as Mesopotamia), encompassing several distinct cultures and spanning a period from the 10th millennium BC, when the first permanent structures were built in the 6th century BC. Among the Mesopotamian architectural accomplishments are the development of urban planning, the courtyard house, and ziggurats. No architectural profession existed in Mesopotamia; however, scribes drafted and managed construction for the government, nobility, or royalty.

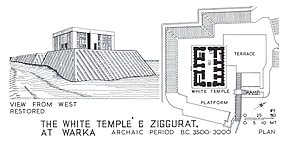

The study of ancient Mesopotamian architecture is based on available archaeological evidence, pictorial representation of buildings, and texts on building practices. According to Archibald Sayce, the primitive pictographs of the Uruk period era suggest that "Stone was scarce, but was already cut into blocks and seals. Brick was the ordinary building material, and with it cities, forts, temples and houses were constructed. The city was provided with towers and stood on an artificial platform; the house also had a tower-like appearance. It was provided with a door which turned on a hinge, and could be opened with a sort of key; the city gate was on a larger scale, and seems to have been double. ... Demons were feared who had wings like a bird, and the foundation stones – or rather bricks – of a house were consecrated by certain objects that were deposited under them."[1]

Scholarly literature usually concentrates on the architecture of temples, palaces, city walls and gates, and other monumental buildings, but occasionally one finds works on residential architecture as well.[2] Archaeological surface surveys also allowed for the study of urban form in early Mesopotamian cities.

Building materials[]

Sumerian masonry was usually mortarless although bitumen was sometimes used. Brick styles, which varied greatly over time, are categorized by period.[4]

- Patzen 80×40×15 cm: Late Uruk period (3600–3200 BC)

- Riemchen 16×16 cm: Late Uruk period (3600–3200 BC)

- Plano-convex 10x19x34 cm: Early Dynastic Period (3100–2300 BC)

The favoured design was rounded bricks, which are somewhat unstable, so Mesopotamian bricklayers would lay a row of bricks perpendicular to the rest every few rows. The advantages to plano-convex bricks were the speed of manufacture as well as the irregular surface which held the finishing plaster coat better than a smooth surface from other brick types.

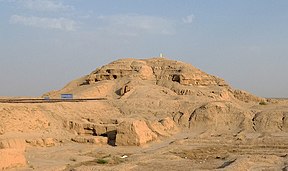

Bricks were sun baked to harden them. These types of bricks are much less durable than oven-baked ones so buildings eventually deteriorated. They were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This planned structural life cycle gradually raised the level of cities, so that they came to be elevated above the surrounding plain. The resulting mounds are known as tells, and are found throughout the ancient Near East. Civic buildings slowed decay by using cones of coloured stone, terracotta panels, and clay nails driven into the adobe-brick to create a protective sheath that decorated the façade. Specially prized were imported building materials such as cedar from Lebanon, diorite from Arabia, and lapis lazuli from India.

Babylonian temples are massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses, the rain being carried off by drains. One such drain at Ur was made of lead. The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enamelled tiles. The walls were brilliantly coloured, and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. Painted terracotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster. Assyria, imitating Babylonian architecture, also built its palaces and temples of brick, even when stone was the natural building material of the country – faithfully preserving the brick platform, necessary in the marshy soil of Babylonia, but little needed in the north.

Decoration[]

As time went on, however, later Assyrian architects began to shake themselves free of Babylonian influence, and to use stone as well as brick. The walls of Assyrian palaces were lined with sculptured and coloured slabs of stone, instead of being painted as in Chaldea. Three stages may be traced in the art of these bas-reliefs: it is vigorous but simple under Ashurnasirpal II, careful and realistic under Sargon II, and refined but wanting in boldness under Ashurbanipal.

In Babylonia, in place of the bas relief, there is greater use of three-dimensional figures in the round – the earliest examples being the statues from Girsu, that are realistic if somewhat clumsy. The paucity of stone in Babylonia made every pebble precious, and led to a high perfection in the art of gem-cutting. Two seal-cylinders from the age of Sargon of Akkad are among the best examples of their kind. One of the first remarkable specimens of early metallurgy to be discovered by archaeologists is the silver vase of Entemena. At a later epoch, great excellence was attained in the manufacture of such jewellery as earrings and bracelets of gold. Copper, too, was worked with skill; indeed, it is possible that Babylonia was the original home of copper-working.

The people were famous at an early date for their embroideries and rugs. The forms of Assyrian pottery are graceful; the porcelain, like the glass discovered in the palaces of Nineveh, was derived from Egyptian models. Transparent glass seems to have been first introduced in the reign of Sargon. Stone, clay and glass were used to make vases, and vases of hard stone have been dug up at Girsu similar to those of the early dynastic period of Egypt.

Urban planning[]

The Sumerians were the first society to construct the city itself as a built and advanced form. They were proud of this achievement as attested in the Epic of Gilgamesh, which opens with a description of Uruk—its walls, streets, markets, temples, and gardens. Uruk itself is significant as the centre of an urban culture which both colonized and urbanized western Asia.

The construction of cities was the end product of trends which began in the Neolithic Revolution. The growth of the city was partly planned and partly organic. Planning is evident in the walls, high temple district, main canal with harbor, and main street. The finer structure of residential and commercial spaces is the reaction of economic forces to the spatial limits imposed by the planned areas resulting in an irregular design with regular features. Because the Sumerians recorded real estate transactions it is possible to reconstruct much of the urban growth pattern, density, property value, and other metrics from cuneiform text sources.

The typical city divided space into residential, mixed use, commercial, and civic spaces. The residential areas were grouped by profession.[5] At the core of the city was a high temple complex always sited slightly off of the geographical centre. This high temple usually predated the founding of the city and was the nucleus around which the urban form grew. The districts adjacent to gates had a special religious and economic function.

The city always included a belt of irrigated agricultural land including small hamlets. A network of roads and canals connected the city to this land. The transportation network was organized in three tiers: wide processional streets (Akkadian:sūqu ilāni u šarri), public through streets (Akkadian:sūqu nišī), and private blind alleys (Akkadian:mūṣû). The public streets that defined a block varied little over time while the blind-alleys were much more fluid. The current estimate is 10% of the city area was streets and 90% buildings.[6] The canals; however, were more important than roads for good transportation.

Houses[]

The materials used to build a Mesopotamian house were similar but not exact as those used today: mud brick, mud plaster and wooden doors, which were all naturally available around the city,[7] although wood was not common in some cities of Sumer. Most houses had a square centre room with other rooms attached to it, but a great variation in the size and materials used to build the houses suggest they were built by the inhabitants themselves.[8] The smallest rooms may not have coincided with the poorest people; in fact, it could be that the poorest people built houses out of perishable materials such as reeds on the outside of the city, but there is very little direct evidence for this.[9]

Residential design was a direct development from Ubaid houses. Although Sumerian cylinder seals depict reed houses, the courtyard house was the predominant typology, which has been used in Mesopotamia to the present day. This house called é (Cuneiform: